Mexikid Summary, Characters, Analysis and Themes

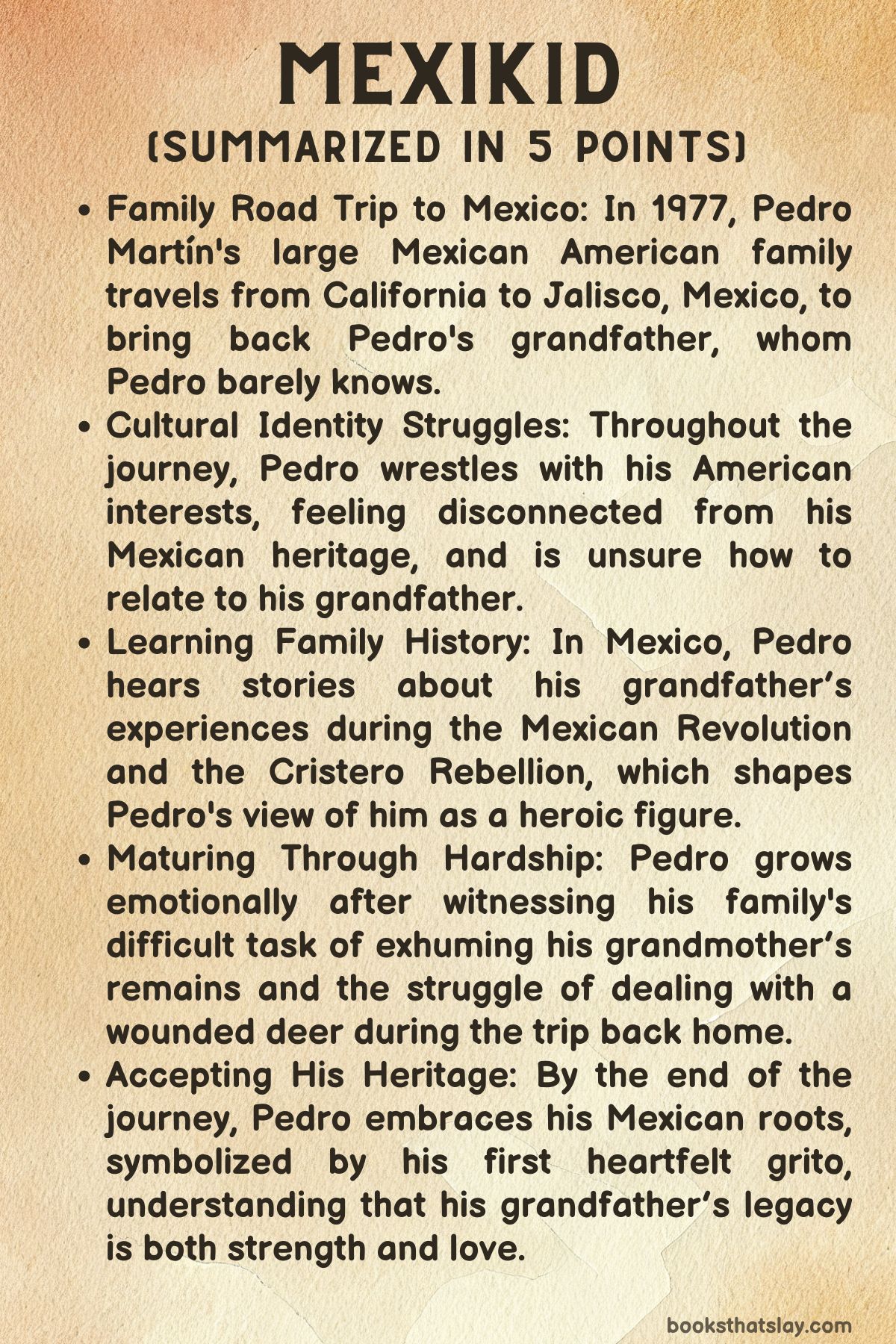

Mexikid (2023), by Pedro Martín, is a middle-grade graphic memoir about identity, heritage, and family. Set in the late 1970s, it follows young Pedro on a life-changing road trip from California to Mexico to bring his grandfather back to the U.S. Along the way, Pedro navigates the clash between his American upbringing and his Mexican roots, gradually deepening his understanding of his family’s history and culture.

Through humor, adventure, and self-discovery, Martín crafts a heartfelt coming-of-age tale, capturing the struggles and joys of growing up between two worlds.

Summary

In 1977, young Pedro Martín lives in a bustling Mexican American household in Watsonville, California.

Though life with his nine siblings is chaotic, the family decides to undertake a massive road trip to Jalisco, Mexico, to bring back Pedro’s grandfather. Pedro hardly knows his “Abuelito,” and his Americanized interests, like comic books and Star Wars, make him nervous about connecting with this stern figure from another world.

His older siblings try to reassure him, saying their grandfather has lived through remarkable experiences, but Pedro remains unsure of what to expect.

The journey south is eventful. They pack a Winnebago and a truck full of children and supplies, driving for days without stopping at the roadside attractions Pedro dreams of.

Along the way, the family faces challenges, such as border officials confiscating some of their possessions. This loss is hard for Pedro, but a visit to a Mexican shop in Tijuana excites him as he discovers new toys and treats.

His father’s emotional outburst—a mix of joy and sorrow triggered by the sound of mariachi music—makes Pedro realize how deeply connected his parents are to their homeland. Yet, feeling out of place in his Mexican heritage, Pedro imitates Fonzie’s catchphrase from Happy Days rather than expressing a traditional grito.

As they drive deeper into Mexico, the family encounters mechanical troubles, but a small-town mechanic, grateful for their father’s earlier kindness, helps repair the vehicle.

Finally, they arrive in Pegueros, where Pedro begins to learn about his family’s history. A local barber, giving Pedro a horrendous haircut meant to resemble a famous Mexican singer, shares stories of Pedro’s grandfather surviving the Cristero Rebellion.

Gradually, Pedro starts to see his grandfather as a heroic figure, even likening him to a “Mexican Jedi” after hearing tales of his bravery.

Over the next few weeks, Pedro explores his roots. He tries (and fails) at local courting traditions and spends time with cousins, while slowly coming to appreciate his grandfather’s quiet strength.

A somber moment comes when Pedro helps his father and grandfather retrieve his grandmother’s remains from a threatened graveyard, a task that brings him closer to understanding the family’s burdens.

As the return trip to California approaches, Pedro continues to adjust to the reality of who his grandfather truly is—less a superhero and more a wise, resilient man.

They experience lighter moments, like his father’s clumsy driving lesson, but Pedro still struggles to reconcile his image of his grandfather with the reality of the man.

The trip ends with a dramatic encounter with a wounded deer, where Pedro’s attempts to help the suffering animal only lead to frustration. This painful experience, along with his growing realization that his grandfather is both tough and tender, marks a turning point in Pedro’s maturity.

In the end, a family celebration brings everything full circle, and Pedro, feeling a complex mix of emotions, finally releases his first authentic grito, symbolizing his newfound understanding of his heritage.

Characters

Pedro Martín

Pedro is the protagonist of Mexikid, a young boy grappling with his identity as a Mexican American. Living in Watsonville, California, in a large family, Pedro has grown up with a deep sense of being American, shown by his love for Star Wars, comic books, and television shows like Happy Days.

His journey to Mexico with his family serves as a pivotal moment in his life, as he gradually becomes more aware of his Mexican heritage and the rich cultural history that shapes his identity. Pedro’s view of his grandfather, whom he initially sees as a distant, almost mythical figure, transforms as he comes to appreciate the depth of his grandfather’s life experiences.

Through his observations of family traditions, his exposure to Mexican customs, and his increasing responsibilities, Pedro experiences significant personal growth. By the end of the memoir, he begins to understand the importance of family, the complexity of identity, and what it means to be strong for those you love.

Pedro’s maturation is symbolized by his ability to express the grito, a cry that reflects his emotional development and his connection to his heritage.

Pedro’s Grandfather (Abuelito)

Abuelito plays a central role in Pedro’s coming-of-age. Initially, Pedro imagines his grandfather as a near-legendary figure, almost like a “Mexican Jedi” due to his strength and the stories of his adventures during the Mexican Revolution.

However, over time, Pedro realizes that his grandfather is not a superhero but a man of wisdom and resilience. Abuelito’s character is defined by his quiet strength, deep connection to the land, and adherence to family traditions.

His refusal to engage in violence when Pedro expects him to avenge the family in the fireworks incident demonstrates his moral grounding and pragmatism.

He teaches Pedro valuable lessons about kindness, patience, and the importance of heritage.

Through his actions, rather than dramatic stories, Abuelito shows Pedro that true strength often lies in gentleness, understanding, and care for others. His bond with Pedro grows as he imparts his wisdom about family values, personal responsibility, and tradition.

Pedro’s Father

Pedro’s father is a practical, hardworking man who values family and tradition. He is depicted as a figure of authority, often making decisions that frustrate Pedro, especially during the road trip to Mexico, such as his refusal to stop at tourist attractions to save money.

However, as the story progresses, Pedro begins to appreciate his father’s perspective, especially his philosophy of kindness toward strangers. His father’s ability to build relationships with others, even across borders, plays a key role in ensuring the family’s safe and successful journey.

His father is also shown to be someone who bears the burden of responsibility with quiet strength, as seen in the emotional scenes where he disinters Pedro’s grandmother’s remains with his own father.

This act of love and respect for his parents serves as a powerful demonstration to Pedro of the sacrifices and emotional complexity that come with familial duty.

Pedro’s Mother

Pedro’s mother is the glue that holds the family together. She is depicted as a nurturing figure who ensures the family’s well-being and manages the chaos of nine children with patience and love.

Her actions throughout the memoir reflect her commitment to preserving the family’s Mexican heritage, as seen when she and her husband prepare to bring donations to Mexico.

Her emotional wisdom is evident when she explains to Pedro that people can be both happy and sad at the same time, comparing his grandfather to an avocado—tough on the outside, but filled with nourishment and containing a seed for the future.

This metaphor encapsulates her understanding of the human experience and the challenges of balancing cultural identities. Her compassion and care help Pedro process the many emotional challenges he faces during the trip, guiding him toward a more mature understanding of life.

Pedro’s Older Siblings

Pedro’s older siblings, particularly his sister Lila and his brother Sal, play supporting roles in his growth.

Lila, who is closest to Pedro in age, often offers him advice and emotional support, helping him navigate his feelings of confusion and frustration throughout the journey. She understands the dynamics of their family and offers Pedro insight into their grandfather’s true nature.

Her guidance during moments of emotional turmoil, such as when Pedro feels overwhelmed by the events surrounding the deer’s death, provides him with the wisdom he needs to come to terms with his own emotions.

Sal, on the other hand, is more of a practical figure in the narrative, helping with logistics and assisting their father during the trip.

He represents the family’s shared responsibility and acts as a role model for Pedro as he begins to take on more adult responsibilities during the road trip.

Pedro’s Grandmother (Abuelita)

Though deceased before the events of the memoir, Pedro’s grandmother’s presence looms large in the family’s journey.

Her remains, which must be relocated to ensure her proper resting place, serve as a symbol of the family’s ties to their Mexican roots. The act of disinterring her body and reburial plays a significant role in the family’s emotional journey.

It forces Pedro to confront the realities of death and the importance of honoring one’s ancestors. His grandmother is remembered as a loving figure, and her role in the family’s traditions is preserved through the actions of her children and grandchildren.

Pedro’s Younger Siblings

Pedro’s younger siblings, though not explored in as much depth, add a sense of chaos and innocence to the family’s dynamics.

They provide comic relief during tense moments and reflect the varying degrees of connection to their Mexican heritage.

Their playful teasing and bickering contrast with Pedro’s internal struggles, highlighting his journey toward greater maturity.

At the same time, their vulnerability, particularly in the scene with the deer, brings out Pedro’s protective instincts and signals his growing sense of responsibility toward his family.

Analysis and Themes

The Complexity of Identity in a Bicultural Context

One of the central themes in Mexikid is the complexity of identity, particularly within a bicultural context. Pedro’s journey throughout the memoir highlights the tensions between his American and Mexican identities, as well as his desire to reconcile these seemingly opposing aspects of himself.

Born in the United States to Mexican parents, Pedro struggles with the feeling of being “not Mexican enough,” exemplified by his inability to release a proper grito, a deeply Mexican expression of emotion.

His American interests—comic books, Star Wars, and television shows like Happy Days—clash with the cultural expectations he assumes his Mexican grandfather holds. Pedro’s fear of being judged for these interests symbolizes the broader struggle of bicultural individuals who must navigate the sometimes competing pressures of different cultural worlds.

Throughout the trip, Pedro’s experiences in Mexico and his interactions with his family—particularly his grandfather—lead him to a deeper understanding of how these two identities can coexist.

His growing realization that he is both a product of Mexican traditions and American culture suggests a more nuanced perspective on identity, one that rejects rigid categorizations and embraces a fluid, multifaceted self.

The Evolution of Heroism and the Perception of Masculinity

The narrative places a strong emphasis on Pedro’s shifting perception of heroism and masculinity, as embodied by his grandfather.

Initially, Pedro views his grandfather through the lens of traditional, larger-than-life masculine tropes—an unyielding, powerful figure akin to the “Mexican Jedi” or a Western gunslinger, filled with stories of adventure and survival.

This idealization reflects Pedro’s youthful understanding of masculinity as synonymous with physical strength, bravery, and action.

However, as Pedro spends more time with his grandfather, his notion of heroism evolves from one based on mythic feats to one grounded in wisdom, resilience, and quiet strength.

His grandfather’s refusal to retaliate against the boy who cheated Pedro, and his advice about treating animals humanely, offer alternative models of masculinity that value compassion, restraint, and ethical behavior over brute force.

By the end of the memoir, Pedro learns that true heroism is not about performing grandiose acts but rather about showing responsibility, care, and emotional intelligence. This evolution mirrors Pedro’s own coming-of-age journey as he learns to embody these values in his own life, particularly in his interactions with his family.

The Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural and Personal Legacy

A significant theme in Mexikid is the intergenerational transmission of both cultural traditions and personal legacies. Pedro’s relationship with his grandfather serves as a conduit through which he learns about his family’s history, the values that have shaped them, and his own role within this lineage.

His grandfather, who lived through historical events like the Cristeros Rebellion, represents a direct link to Mexico’s past and a repository of family wisdom.

Pedro’s growing admiration for his grandfather is not merely based on his grandfather’s physical strength or adventurous stories, but on the deeper recognition that much of Pedro’s own identity—his artistic abilities, his family’s values, and even his Mexican American heritage—can be traced back to this man.

The metaphor of the avocado that Pedro’s mother uses, with its tough exterior but nourishing interior and seed for future generations, encapsulates the theme of legacy. Pedro is not just inheriting his grandfather’s stories, but also the responsibility to carry forward his family’s traditions and values, a role he gradually comes to embrace.

This theme also explores the idea that cultural transmission is not a passive act; rather, it requires active engagement and reflection on the part of each new generation.

The Emotional Complexity of Growing Up: Joy, Loss, and the Maturation Process

Pedro’s maturation over the course of the memoir is deeply intertwined with the emotional complexity of growing up, particularly the simultaneous experiences of joy and loss.

His journey from childhood to adolescence is marked by moments of excitement, such as his growing confidence in Mexico and his attempts at romantic courtship, but it is also underscored by more somber realizations.

The experience of helping to exhume his grandmother’s remains and witnessing the death of the deer on the family’s journey home force Pedro to confront the inevitability of death and the imperfections of the adult world.

These events, which blur the lines between life and death, joy and sorrow, highlight the bittersweet nature of growing up.

Pedro’s realization that life is filled with contradictions—such as his grandfather’s mix of kindness and distance, or the simultaneous feelings of happiness and grief during family gatherings—culminates in his ability to finally release a proper grito. This cry, which Pedro had previously been unable to produce, symbolizes his acceptance of the emotional complexity of life.

Rather than viewing maturity as a linear process toward happiness or strength, the memoir presents it as an intricate balance of joy, loss, responsibility, and emotional vulnerability.

The Role of Physical and Emotional Journeys in Self-Discovery

In Mexikid, the physical journey from California to Jalisco mirrors Pedro’s internal journey of self-discovery.

Road trips in literature often serve as metaphors for personal growth, and Pedro’s family’s road trip is no exception. Each stop along the way—the breakdown of the Winnebago, the visit to the cemetery, the various interactions with Mexican locals—provides Pedro with opportunities to learn more about his family, his heritage, and himself.

The physical movement through different landscapes reflects Pedro’s evolving emotional landscape, as he navigates feelings of cultural displacement, admiration for his grandfather, and confusion about his own role within his family.

The challenging and sometimes dangerous roads they travel through also symbolize the unpredictable nature of the maturation process; just as the family must face unexpected detours and obstacles, Pedro must confront difficult truths about death, responsibility, and his own expectations of others.

The journey home, in particular, represents a crucial turning point in Pedro’s self-understanding. It is during this leg of the trip that Pedro takes on more responsibility, both literally when he attempts to drive and emotionally when he supports his grandfather.

By the time the family returns to California, Pedro is not the same boy who first set out, but a more mature and reflective version of himself, having completed both a physical and emotional odyssey.

The Tension Between Individual Desires and Family Obligations

Another major theme in Mexikid is the tension between individual desires and family obligations, a recurring challenge for Pedro as he grows up.

Throughout the memoir, Pedro is torn between his personal interests—his love of American culture, his desire for adventure and independence—and the responsibilities that come with being part of a large, close-knit Mexican American family.

His frustration with the cramped conditions of the family’s motorhome, his resentment when his father refuses to stop at tourist attractions, and his initial lack of enthusiasm for his grandfather’s arrival all stem from a desire for individual freedom. However, the journey to Mexico teaches Pedro that being part of a family involves sacrifices and duties that cannot be easily avoided.

The family’s mission to bring Pedro’s grandfather back to the United States, which includes disinterring his grandmother’s remains, is a powerful metaphor for the weight of family obligations. In the end, Pedro learns that his personal growth is deeply connected to his ability to embrace these responsibilities, rather than seeing them as burdens.

His eventual pride in being his grandfather’s “seed” signifies his acceptance of the idea that individual identity is not separate from, but rather deeply intertwined with, family legacy and community.