Midnight is the Darkest Hour Summary, Characters and Themes

Midnight is the Darkest Hour by Ashley Winstead is a gothic Southern mystery that drips with dread, desire, and dark secrets.

Set in the shadowy town of Bottom Springs, Louisiana—a place ruled by fire-and-brimstone faith and superstition—it follows Ruth Cornier, a quiet preacher’s daughter hiding a monstrous past. With lyrical prose and an eerie atmosphere, Ashley Winstead weaves a coming-of-age tale wrapped in folklore, trauma, and forbidden love. The story interrogates sin, salvation, and the line between myth and truth, asking: Who gets to be saved—and who gets sacrificed?

Summary

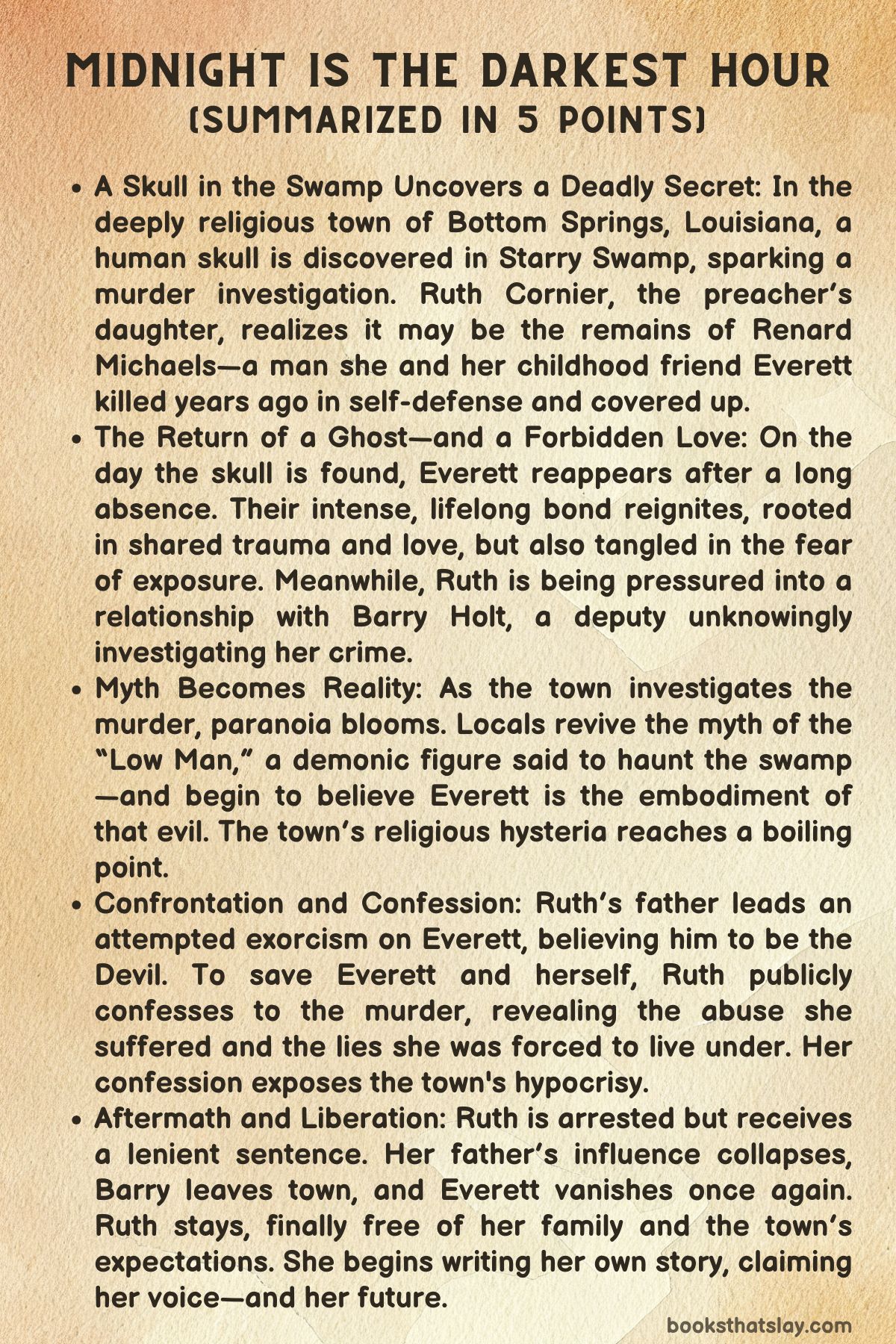

In the deeply religious swamp town of Bottom Springs, Louisiana, everyone fears the Devil—but Ruth Cornier knows evil can look a lot more human.

Ruth, the reclusive daughter of a hellfire preacher, lives a small, silent life as a librarian. Her days are ruled by guilt, fear, and the weight of her town’s judgment. But Ruth harbors a terrible secret.

Years ago, in the thick of the swamp, she and her best friend Everett Duncan killed a man named Renard Michaels. It was self-defense, but they never told a soul. They disposed of the body in Starry Swamp and promised to protect each other forever.

Now, the past has clawed its way to the surface—literally. A human skull is discovered, and Bottom Springs is gripped by hysteria. Ruth senses the end is near. On the same day, Everett reappears, mysteriously drawn back after more than a year away.

Their bond rekindles instantly, thick with shared trauma and unresolved feelings. As the investigation closes in, their secret threatens to unravel, piece by bloody piece.

Ruth is trapped between two lives. In one, she is the dutiful daughter, courted by Barry Holt, a sweet but naive deputy who sees her as his salvation.

In the other, she’s Everett’s—wild, untamed, and honest. Their childhood connection was forged in loneliness, pain, and whispered stories beneath the Medusa tree, a place of both safety and darkness.

But now, the story they’re trapped in is real. The legend of the “Low Man”—a local myth about a devilish figure who lives in the swamp—is resurrected, and townspeople begin to see Everett as its human form.

Flashbacks reveal Ruth’s oppressive upbringing under her tyrannical father and cold mother. She was raised on shame and sin, conditioned to believe that even her thoughts could condemn her. Everett, with his own abusive past, became her lifeline.

Together, they created a world outside the one they were given—a world built on books, secrets, and survival.

As more evidence surfaces—including clues that point directly to Ruth—the investigation grows dangerous.

Barry starts to suspect Everett and pushes Ruth toward marriage, urged on by her father’s desire to “save” her. Meanwhile, Everett is spiraling, convinced he must sacrifice himself to protect Ruth from ruin.

The town descends into religious frenzy. Ruth’s father fuels the fire with apocalyptic sermons, and the line between myth and mob justice vanishes.

When Everett is nearly lynched during an exorcism staged by Ruth’s father, Ruth can no longer stay silent. In a moment of bravery and reckoning, she confesses everything—about the murder, the cover-up, the abuse, and the lies that built Bottom Springs’ so-called righteousness.

The fallout is immense. Ruth is arrested but treated with leniency once the truth is revealed. Her father’s reputation crumbles.

Barry, broken by the revelations, leaves town. And Everett—whether out of guilt or freedom—disappears again, swallowed by the swamp that shaped them.

Ruth stays behind, no longer the obedient girl her parents wanted, nor the haunted woman she once was. She begins writing her story at last, claiming a voice long denied. Midnight is the Darkest Hour closes not with salvation, but with something better: Ruth’s own liberation.

Characters

Ruth Cornier

Ruth is the complex protagonist of Midnight is the Darkest Hour, a woman whose life has been shaped by oppressive religious upbringing and a deeply tragic secret. As the daughter of the fire-and-brimstone preacher in Bottom Springs, she is bound by the expectations of her devout family and town.

Ruth is initially portrayed as a quiet, obedient librarian, but underneath this facade is a woman haunted by guilt and fear of damnation. Her early life in the stifling, judgmental environment shapes her desire to escape, which she finds through a complicated and intense relationship with Everett Duncan, her childhood friend.

Ruth’s emotional and psychological struggles are the heart of the novel, as she grapples with the fallout of a murder she committed at seventeen, the impact of that act on her identity, and her attempts to navigate her feelings for both Everett and Barry Holt, the deputy investigating the murder.

Throughout the novel, Ruth moves from silence and suppression to an eventual confrontation with her own truths, ultimately finding the strength to expose the dark secrets that have defined her existence.

Everett Duncan

Everett is Ruth’s enigmatic and protective childhood friend, and his return to Bottom Springs marks a turning point in the narrative. Raised by an abusive father, Everett has a dark and troubled past that mirrors Ruth’s own struggles.

His return after a year-long absence signals the reawakening of the guilt and fear they both carry. As a central figure in Ruth’s life, Everett shares in the burden of their shared secret: the murder of Renard Michaels, a man they killed in self-defense years earlier.

His emotional connection to Ruth is intense, and their bond is marked by a mixture of love, guilt, and mutual dependence. Everett is constantly wrestling with his own nature, questioning whether he is destined to become like his violent father.

His internal conflict about his identity as both protector and perpetrator adds depth to his character, especially as the town begins to view him as a possible embodiment of the “Low Man,” a local legend tied to evil. Everett’s motivations and actions are driven by a desire to shield Ruth from the fallout of their past, even as the pressure mounts around them.

Barry Holt

Barry Holt is the deputy sheriff of Bottom Springs and the man Ruth’s parents want her to marry. He is portrayed as the opposite of Everett in many ways: dependable, law-abiding, and emotionally invested in Ruth’s future.

Barry represents the life Ruth is expected to live, a life of conformity and devotion to societal and familial expectations. However, as the investigation into Renard’s death intensifies, Barry becomes a source of tension for Ruth.

His increasing suspicion of Everett, as well as his growing closeness to Ruth, puts a strain on their relationship. While Ruth initially sees Barry as a potential escape from her oppressive family, her emotional attachment to Everett complicates this path.

As the novel progresses, Barry’s role shifts from potential suitor to an investigator entangled in the town’s hysteria, and his relationship with Ruth unravels as she comes to terms with her past.

Ruth’s Parents

Ruth’s parents, particularly her father, are embodiments of the oppressive religious atmosphere that dominates her upbringing. Her father is a fire-and-brimstone preacher who imposes a strict and fear-driven moral code on Ruth, ensuring that she is both spiritually and emotionally repressed.

His dominance over her life is a significant factor in her desire to escape Bottom Springs. Her mother, while less overtly abusive, is emotionally cold and judgmental, reinforcing the harsh environment that Ruth has struggled against throughout her life.

The suffocating control of her parents is a major source of Ruth’s guilt and shame, and their presence is a constant reminder of the life she is expected to lead—a life that would stifle her identity and desires.

Themes

The Struggle Between Religious Control and Personal Liberation

One of the most prominent themes in Midnight is the Darkest Hour revolves around the oppressive control of religious authority and the protagonist Ruth’s attempt to break free from it. Ruth’s upbringing in a rigidly religious home, under the rule of her father, who is a fire-and-brimstone preacher, defines much of her internal conflict.

Her father’s doctrine imposes a sense of constant guilt, fear of damnation, and a deep belief in an all-seeing, punishing God. Ruth’s childhood is stifled by the constant pressure to adhere to these rigid beliefs, where questioning anything outside of religious dogma is not only frowned upon but considered sinful.

As Ruth grows older, she begins to grapple with her personal desires, her questioning of the town’s values, and her emerging need for freedom from the oppressive religious framework that has defined her entire life. The tension between her desire for freedom and her deep-rooted fear of divine punishment showcases the inner turmoil of trying to reconcile personal truth with religious guilt.

The town of Bottom Springs, steeped in superstition and extreme religious fervor, symbolizes the larger societal structure that aims to suppress individual identity. Ruth’s relationships—particularly with Everett—offer her a glimpse of a life beyond the constraints of her father’s doctrine.

The tension between her desire for freedom and her fear of damnation becomes a central part of her emotional conflict. In the end, Ruth’s journey to liberation becomes not just an escape from her family but also an act of reclaiming her own identity, free from the control of religious authority that has stunted her emotional and spiritual growth.

The Weight of Trauma and the Legacy of Violence

Another key theme that runs throughout Midnight is the Darkest Hour is the exploration of trauma, specifically Ruth’s involvement in the death of Renard Michaels. The murder, which Ruth and Everett committed years ago in self-defense, casts a long, dark shadow over Ruth’s life, constantly resurfacing in her thoughts and complicating her relationships.

Ruth’s inability to move beyond this trauma is intricately linked to her ongoing guilt, which is magnified by the fear of eternal damnation preached by her father. The narrative skillfully delves into Ruth’s psyche as she grapples with the psychological and emotional consequences of her violent past.

The trauma of the murder is not just personal but communal, affecting not only Ruth and Everett but also the entire town of Bottom Springs, which is haunted by dark myths, like the legend of the “Low Man.” Ruth’s past actions, hidden for so long, are inevitably brought into the light, and the town’s reaction is to seek out a scapegoat, amplifying the idea that the consequences of past violence are never truly buried.

The novel examines how trauma becomes a legacy, passed down not just through familial ties but also through societal narratives and fears, like the persistent mythology of evil in the swamp. The weight of Ruth’s past actions serves as both a personal burden and a reflection of the violence that permeates the larger world.

Myth, Folklore, and the Thin Line Between Reality and Legend

The theme of myth and folklore plays a significant role in shaping the events and perceptions within the novel. The legend of the “Low Man,” a dark figure that preys on sinners, is an ever-present force in the story. This myth not only adds an element of gothic mystery but also becomes a vehicle for the town’s paranoia and religious fervor.

As the investigation into Renard’s death progresses, the townspeople’s fear of evil manifests in their belief that Everett is the embodiment of this legend. The myth becomes a way for the community to externalize its fears and moral judgments, projecting onto Everett the dark, seductive qualities attributed to the “Low Man.”

The interplay between myth and reality is central to Ruth’s experience as well. The Medusa tree, a childhood refuge for Ruth and Everett, becomes symbolic of their shared secret and their escape from the oppressive world they inhabit.

The physical and emotional spaces that the characters occupy—like the swamp, the tree, and the church—become intertwined with local myths, blurring the lines between what is real and what is imagined. Ruth’s struggle to distinguish between her guilt, her desires, and the dark forces around her reflects a larger existential crisis where personal identity is often shaped by the myths and stories that surround it.

In the end, the novel suggests that myths are not just stories; they are powerful forces that influence behavior, shape perceptions, and can even dictate the course of events.

The Cost of Emotional Intimacy

At the heart of Ruth’s emotional journey is her complex and intense relationship with Everett, which is inextricably linked to guilt, love, and the quest for redemption. Their shared history of violence binds them in a way that no one else can understand, and their emotional bond grows deeper as the novel progresses.

Yet, their relationship is also fraught with a constant undercurrent of guilt. Ruth’s love for Everett is intertwined with the trauma of their past, and this love becomes a form of emotional punishment as much as it is a source of solace.

Their intimacy, rather than being a safe haven, becomes a site of emotional conflict, where Ruth questions whether their bond is pure or simply a manifestation of their shared guilt and need for redemption. Everett’s internal struggle about his nature—whether he is inherently evil due to his father’s legacy, and whether he deserves Ruth’s love—further complicates their relationship.

Ruth’s journey of emotional liberation is not just about escaping the grip of her father’s religious rule but also about coming to terms with her love for Everett. Her final act of confession is not just a public admission of guilt for Renard’s murder but also an acknowledgment of her emotional connection to Everett.

It represents her ultimate rejection of the toxic relationship with her father, as well as her refusal to live in silence and shame. Through this act of honesty, Ruth seeks both personal redemption and the possibility of a future that is not defined by guilt or the past.

The Power of Silence and the Fight for Personal Voice

One of the most subtle yet powerful themes in Midnight is the Darkest Hour is the theme of silence and the struggle for personal voice. Ruth’s entire life has been marked by silence: the silence imposed by her father’s authoritarian beliefs, the silence around the murder, and the silence of a town that refuses to acknowledge its dark truths.

Throughout the novel, Ruth is confronted by the oppressive weight of keeping secrets—both personal and communal—and the toll that silence takes on her mental and emotional health. Her final decision to speak out, to confess publicly and break free from the silencing power of her father, marks a moment of profound personal transformation.

The act of speaking the truth, of breaking the silence that has governed her life, is not just an act of redemption but also a reclaiming of agency. Ruth’s confession, while bringing consequences, is ultimately an assertion of her own voice in a world that has tried to define her by others’ beliefs, fears, and expectations.

In this way, the novel highlights the power of personal voice and the liberating force of truth-telling in the face of shame, fear, and control.