Midnight Shift Summary, Characters and Themes | Cheon Seon-ran

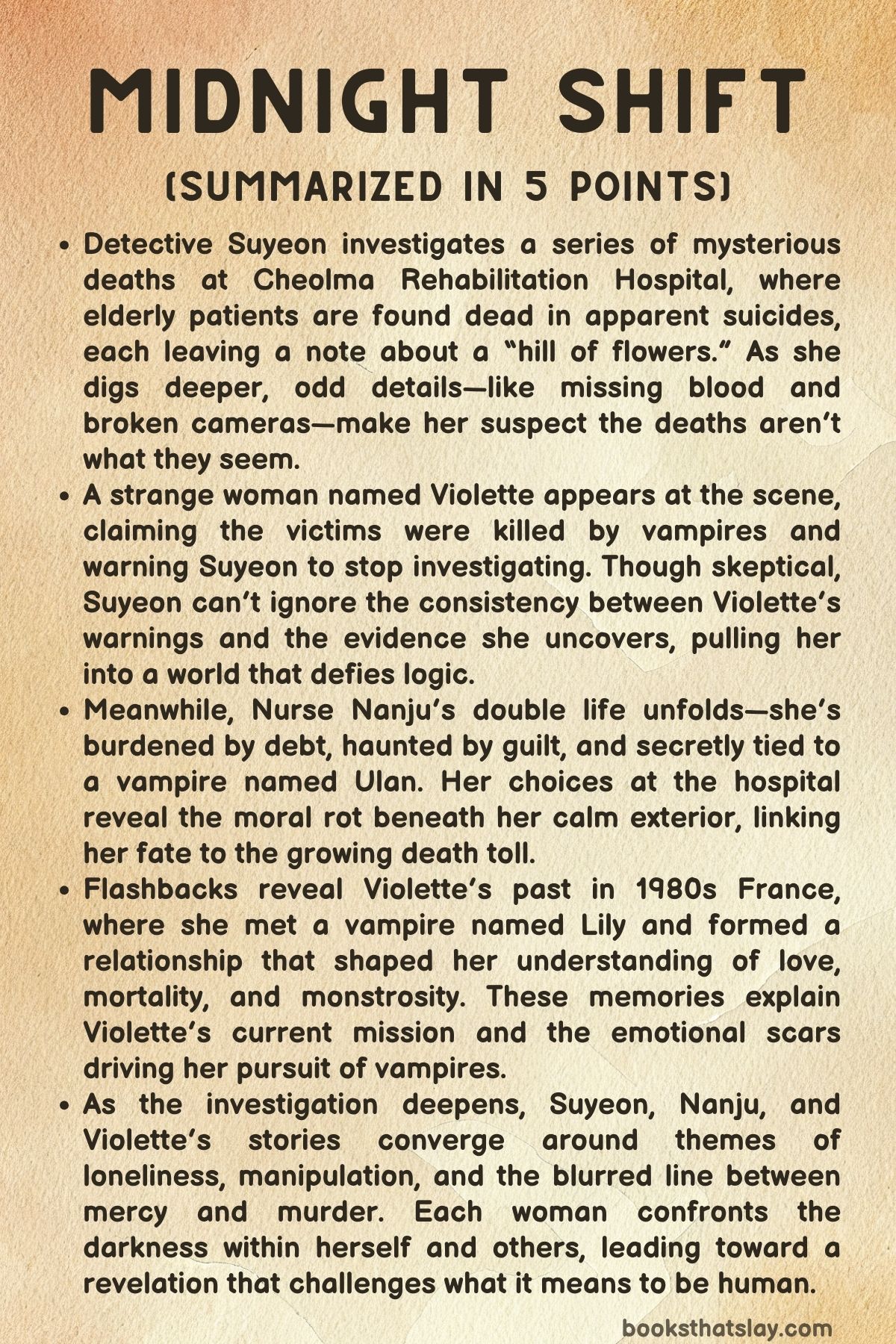

Midnight Shift by Cheon Seon-ran is a haunting contemporary mystery that blends crime investigation with gothic supernatural elements. Set in South Korea, the story follows Detective Su-yeon as she investigates a series of mysterious suicides at Cheolma Rehabilitation Hospital.

What begins as a procedural inquiry into elderly patients’ deaths unfolds into a chilling confrontation between humanity and something far older and darker. Through intersecting narratives—spanning detectives, nurses, and vampires—the book explores loneliness, guilt, and the fragile line between compassion and cruelty. Cheon crafts a story that is both intimate and unsettling, where every act of mercy carries a shadow of violence.

Summary

Detective Suyeon arrives at Cheolma Rehabilitation Hospital after yet another elderly patient has jumped to their death. The man’s suicide note, like the others before it, mentions a “hill of flowers.

” It’s the fourth such death in a month, all among aging patients with no family left. When Suyeon examines the body, she notices an odd detail—a crumpled orange paper flower in the man’s hand.

CCTV footage is missing, and her partner Chantae insists it’s just another case of despair in an aging ward. But Suyeon senses something wrong.

Her forensic contact, Jiseon, later confirms that the victims’ injuries lack expected bleeding for their falls, suggesting they were already dead before hitting the ground.

While visiting her favorite patient, Granny Eunshim, Suyeon confronts the emotional toll of her work. The elderly woman, suffering from dementia, mistakes Suyeon for her granddaughter and mentions a long-dead friend as if she were alive.

When Suyeon finds another paper flower under the woman’s bed, Eunshim speaks cryptically of washing bodies and climbing a hill—words echoing the suicide notes. Troubled, Suyeon revisits the hospital that night and encounters a strange woman named Violette.

Pale, silver-haired, and unsettlingly calm, Violette claims the victims were “thrown” and that their killer is not human. When pressed, she names the culprit: a vampire.

Suyeon dismisses her as insane but can’t shake the warning.

A week later, nurse Seo Nanju begins to unravel. Burdened by debt and haunted by her father’s death, she survives by selling stolen hospital morphine to addicts.

Paranoid and sleepless, she becomes convinced that someone is watching her. Her moral boundaries, once fragile, begin to dissolve completely.

Meanwhile, Suyeon investigates another death—a fifth body, showing puncture wounds on the neck just as Violette described. Her skepticism falters.

She begins to suspect someone is staging suicides to hide a pattern of murder.

Flashbacks reveal Violette’s youth in 1980s France, where she met a mysterious barefoot girl named Lily. Lily’s golden eyes and unnatural grace set her apart from other humans.

Their friendship, marked by tenderness and curiosity, turns into a forbidden bond. Lily’s vanishing and reappearances hint at something otherworldly, and when deaths occur around her, Violette realizes that Lily is a vampire.

Yet she loves her nonetheless, accepting the danger that comes with that love.

In the present, Suyeon reluctantly partners with Violette. They investigate Cheolma Hospital together, uncovering signs that the victims may have been manipulated into suicide.

Violette argues that vampires prey not only on blood but on loneliness itself—seducing humans into surrendering their lives. Suyeon learns that Violette hunts vampires for a secret organization, using her half-human nature to bridge the gap between species.

As their uneasy alliance grows, Suyeon’s belief in reason collides with the supernatural truth before her.

Nurse Nanju’s past reveals her as a victim and a perpetrator. Raised in poverty and bitterness, she was drawn into corruption early in her nursing career.

Her encounter with a vampire named Ulan changed everything. Ulan, ancient and manipulative, promised to “free” her from her father’s abuse—and soon her father died, just as he’d predicted.

Over time, Nanju fell completely under his control. Ulan treated her alternately as a pet and a tool, feeding on her dependence and guilt.

When patients began dying at the hospital, she suspected him but felt powerless to stop it.

Meanwhile, Suyeon’s memories deepen her emotional arc. She recalls her mentor Eungyeong, a senior detective who once saved her from suicide and guided her into the police force.

Granny Eunshim’s affection reminds Suyeon of the maternal warmth she lost long ago, making her death all the more devastating. When Eunshim becomes another “suicide,” Suyeon recognizes the pattern—the same “hill of flowers,” the same serenity in death.

She realizes someone is influencing the victims’ minds, convincing them to die peacefully.

Violette’s own history resurfaces through fragmented memories. She was raised by her adoptive parents, Maurice and Claire, until Lily entered her life.

Their love was both tender and tragic. One night, Lily bit Violette to survive but spared her life.

Soon after, Maurice was killed by a vampire—Ulan, the same being now haunting Suyeon’s case. Lily tried to protect Violette but disappeared afterward, leaving behind a necklace.

That trauma hardened Violette, setting her on a path of vengeance.

In the present, Suyeon uncovers the truth: Nurse Seo Nanju and the disgraced nurse from an old morphine scandal, Seo Yeongeun, are the same person. She informs Violette, who concludes that Nanju is aiding Ulan.

The vampire, she explains, manipulates despairing humans to kill themselves. Such deaths blur the moral line—technically suicide, yet spiritually murder.

Together, they prepare to confront Ulan.

Nanju’s world collapses when Ulan kills Granny Eunshim, ignoring her pleas to stop. His justification is chilling—he claims the old woman recognized him, so she had to die.

Realizing she is next, Nanju turns to Violette for help. Violette promises protection but warns that Ulan’s kind only spares those who submit.

The terrified nurse understands that her fate is sealed.

The final confrontation unfolds when Suyeon finds Nanju dead in her apartment, posed as suicide but clearly murdered. As she investigates, Ulan appears—cold, beautiful, and inhuman.

He admits to killing both Nanju and Eunshim, describing his acts as “mercy. ” Suyeon attacks him but is easily overpowered.

Before he can drain her blood, Violette arrives and drives a blade through his heart. Their battle is brutal and tragic, echoing their first encounter decades earlier.

As Ulan dies, he accuses Violette of abandoning him long ago, hinting at an older bond twisted by vengeance. Both are mortally wounded.

Violette dies soon after, leaving Suyeon barely alive.

When Suyeon awakens, she carries two small puncture marks on her neck. She tells no one the truth.

Cheolma Hospital shuts down, the case closed as a cluster of suicides. But Suyeon knows better.

Driving through the city one rainy night, she glimpses Greta, a vampire ally of Violette’s, standing under a streetlight, smiling faintly. The world moves on, indifferent to what hides in its shadows.

Suyeon reflects that loneliness, not blood, is what truly kills—that vampires may simply be mirrors of human despair.

In the end, Midnight Shift is not just a story of murder or monsters but of people who crave connection in a world that forgets them. Every death, every bite, and every act of love stems from the same hunger—to not be alone.

Characters

Detective Suyeon

Detective Suyeon is the emotional and moral core of Midnight Shift, embodying both the analytical sharpness of a detective and the wounded empathy of someone intimately acquainted with loss. Her investigation into the suicides at Cheolma Rehabilitation Hospital begins as a procedural duty but quickly evolves into a personal quest for understanding the nature of despair.

Suyeon’s character is defined by her unyielding intuition—she senses patterns where others see coincidences—and this persistence reflects a deep compassion for the forgotten and discarded. The presence of Granny Eunshim, whom she visits frequently, reveals her yearning for familial warmth, something she lost long ago.

Suyeon’s skepticism toward the supernatural is gradually eroded as she confronts Violette and the unfolding evidence of vampiric influence, forcing her to confront her own loneliness. Her emotional vulnerability, especially in moments remembering her mentor Eungyeong or mourning Eunshim, gives her a human fragility that contrasts with the inhuman forces she faces.

By the end, Suyeon emerges as both survivor and witness—a woman who has seen the veil between humanity and monstrosity torn apart, understanding that loneliness, not bloodlust, is the true curse of existence.

Violette

Violette stands at the center of Midnight Shift as a tragic bridge between the human and the supernatural worlds. Her life, beginning as a lonely French girl adopted from Korea, intertwines innocence, love, and eternal punishment.

The defining relationship of her youth—with Lily, the vampire who both nurtures and curses her—shapes her transformation from naïve child to haunted hunter. Through Lily, Violette learns the paradox of love: it can save and destroy in equal measure.

Her connection with humanity is complicated by her own partial vampiric nature—she hunts monsters like Ulan, yet she herself has lived too long to remain untainted. Violette’s encounters with Suyeon reveal her duality: at once cold and tender, aloof yet deeply protective.

Her past is filled with trauma—her father’s death, Lily’s departure, and her immortality’s heavy price—but she channels this pain into a mission to rid the world of creatures like Ulan. Despite her strength, Violette’s melancholy defines her; she represents the cost of eternal survival and the lingering shadow of love lost.

Her death, quiet and redemptive, closes a cycle of guilt that began decades earlier.

Seo Nanju

Nurse Seo Nanju embodies the novel’s exploration of corruption, despair, and moral erosion. Once an idealistic woman trapped in a web of debt, loss, and systemic exploitation, she descends into moral ambiguity through choices born of desperation.

Her relationship with the vampire Ulan is both her damnation and her attempt at salvation—she mistakes his predatory control for affection, clinging to him as both lover and liberator. Nanju’s descent mirrors the decay of the hospital itself, where patients are drained not only of blood but of hope.

Her actions—selling morphine, lying to the police, covering deaths—reflect how trauma deforms compassion. Yet her fear and eventual defiance of Ulan show flickers of conscience, suggesting that even those consumed by darkness can glimpse regret.

Her eventual death at Ulan’s hands seals her fate as both victim and accomplice, a woman who wanted control but surrendered it entirely. Nanju’s tragedy lies in her humanity: she is neither monster nor saint, but a soul crushed between love, guilt, and survival.

Ulan

Ulan is the embodiment of the cold, predatory intellect that haunts Midnight Shift. A centuries-old vampire, he kills not out of hunger alone but to impose meaning on suffering.

His victims—often lonely, forgotten people—are chosen precisely because their despair invites him. He sees himself as a philosopher of death, interpreting mercy and murder as interchangeable acts.

Ulan’s manipulation of Nanju exposes his psychological cruelty; he does not merely feed on her blood but on her dependency. Yet his character is not devoid of complexity.

His hatred for Lily, his past with Violette’s family, and his warped sense of justice suggest a creature seeking purpose in destruction. In his final confrontation with Violette and Suyeon, Ulan’s arrogance collapses into bitter irony—he dies by the hand of one whose pain he helped create.

He represents the existential void that drives the novel’s philosophy: that evil often begins with loneliness disguised as love.

Lily

Lily, the ancient vampire who once loved Violette, is both mentor and mirror. She personifies the novel’s quiet, sorrowful beauty—a creature who understands that immortality is not freedom but imprisonment in endless loss.

Her affection for Violette is genuine yet inevitably destructive, teaching the girl both tenderness and horror. Through Lily, the story reveals that monsters are not defined by their thirst for blood but by their inability to let go of love.

Her decision to bite Violette without killing her is both an act of compassion and condemnation, gifting her eternal life laced with grief. Lily’s absence echoes through Violette’s adulthood, shaping her into the vampire hunter who carries her necklace as both weapon and relic.

Lily’s presence—seen and unseen—forms the emotional architecture of the book, symbolizing the impossibility of pure love between mortality and eternity.

Granny Eunshim

Granny Eunshim stands as the quiet heart of Midnight Shift, a symbol of the forgotten elderly whose deaths ignite the story. Her interactions with Suyeon reveal the depth of human fragility and the hunger for connection.

Though her dementia makes her confuse reality and memory, her words often carry haunting wisdom, as when she speaks of “washing bodies clean” and “the hill of flowers. ” Her gentle affection—offering yogurt or calling Suyeon her granddaughter—makes her death all the more devastating.

Eunshim represents the emotional stakes of the novel: the way society discards its weakest, making them easy prey for monsters both literal and metaphorical. Even in death, she remains Suyeon’s emotional compass, a reminder that love and care are the only real defenses against despair.

Chantae and Jiseon

Chantae, Suyeon’s colleague, and Jiseon, the forensic expert, act as the pragmatic anchors of the narrative. Chantae’s skepticism contrasts Suyeon’s intuition, reflecting institutional indifference to human suffering—he embodies the weary acceptance that defines a decaying system.

His dismissal of the suicides as “predictable” shows how bureaucracy numbs empathy. Jiseon, meanwhile, provides scientific clarity, confirming the abnormalities Suyeon senses.

Though secondary, both characters highlight the novel’s theme that truth is often ignored not because it is hidden but because it is inconvenient.

Greta

Greta, the bar owner and vampire ally, bridges compassion and darkness. Her presence adds depth to the mythos, revealing that not all vampires are killers.

By helping orphans and aiding Violette, she becomes a symbol of coexistence—a creature who chooses empathy over appetite. Greta’s interactions with Suyeon humanize the supernatural world, showing that even immortals can seek redemption.

Her final appearance, alive and smiling in the rain, closes the story on an ambiguous note: perhaps peace between humans and vampires is possible, or perhaps monsters only smile when they know the hunt never ends.

Themes

Loneliness and Human Isolation

In Midnight Shift, loneliness operates not merely as an emotional state but as a destructive force that blurs the line between the living and the dead. Every major character—Suyeon, Violette, and Nanju—suffers a profound disconnection from others, and this isolation becomes the very medium through which both human and supernatural predation occur.

The elderly patients in Cheolma Rehabilitation Hospital are abandoned by families and institutions alike, reduced to shadows of memory and routine, which renders them perfect prey for the unseen vampire. Suyeon’s solitude, framed through her attachment to the dementia patient Granny Eunshim, underscores the ache of those who reach for connection in sterile places.

Her emotional dependence on this fragile relationship mirrors the old woman’s delusion of seeing loved ones long gone. Violette’s history extends this theme across centuries, revealing how isolation can mutate into obsession.

Her bond with Lily, the vampire who first awakened her to affection and mortality, captures the hunger for companionship that transcends death itself. Nanju’s isolation, meanwhile, is more grounded in social decay—born of poverty, debt, and moral erosion—and drives her into the orbit of Ulan, a creature who exploits her yearning for validation.

The novel suggests that loneliness is both the disease and the bait; vampires in this world do not merely drink blood—they consume despair. By the end, Suyeon’s realization that “loneliness itself was the true predator” transforms the gothic horror into a deeply human commentary on emotional neglect and the silent deaths it breeds.

The Corruption of Love and Compassion

Love in Midnight Shift frequently disguises cruelty, creating a paradox where acts of care and violence become indistinguishable. Violette’s relationship with Lily begins as tender affection but evolves into a painful awakening about the limits of empathy between mortals and immortals.

Lily’s love teaches endurance and suffering simultaneously, demonstrating that intimacy can be a wound that never heals. Suyeon’s devotion to Granny Eunshim is similarly marked by helplessness; her attempts to protect the old woman only deepen her sense of failure when Eunshim dies.

Nanju’s attachment to Ulan represents the most toxic distortion of love—a devotion built on dependence and fear. Believing he understands her pain, she becomes complicit in his murders, rationalizing his evil as affection.

Through these intertwined narratives, the novel examines how love can justify destruction and how compassion, when unanchored from moral clarity, becomes a tool for manipulation. Even Ulan, the vampire, insists that his killings are acts of mercy, claiming his victims desired peace.

This warped tenderness exposes the danger of emotional surrender, where devotion blinds conscience. The author portrays love as an energy that cannot distinguish between nurture and consumption; in both human and vampire realms, affection easily curdles into possession.

Ultimately, the story suggests that compassion without boundaries invites exploitation, and that the purest form of love may lie not in saving others but in allowing them to face the truth of their own suffering.

Death, Memory, and the Desire for Release

Death pervades Midnight Shift as both a physical event and a psychological seduction. The repeated suicides at Cheolma Hospital reflect a collective yearning for escape among the forgotten, but they also mask a deeper pattern of manipulation.

The elderly victims do not simply die—they are guided toward a vision of peace, a “hill of flowers” that promises reunion and rest. This motif transforms death into an illusion of deliverance rather than horror, exposing humanity’s desperate craving for meaning at the end of life.

Suyeon’s investigation gradually reveals that these deaths are not spontaneous acts of despair but orchestrated rituals of erasure, engineered by those who feed on the dying’s surrender. The novel contrasts this human longing for release with the vampire’s curse of immortality; for creatures like Violette and Lily, death becomes the unattainable freedom they envy in mortals.

Memory acts as the bridge between these conditions—Violette carries the trauma of her father’s murder across decades, while Suyeon bears the lingering grief of lost mentors and patients. Their memories refuse to fade, keeping the dead alive in haunting ways that mirror the vampire’s endless existence.

The story argues that the true tragedy is not death itself but the inability to let go—the compulsion to remember pain until it devours the present. In the end, death is portrayed as both an escape and a mirror: those who seek it are consumed by its promise, and those who flee it are condemned to live endlessly within its shadow.

Morality and the Boundaries of Humanity

The question of what it means to be human threads through every moral choice in Midnight Shift, testing compassion against survival and justice against empathy. Suyeon’s moral compass as a detective is constantly challenged by cases that defy rational explanation.

Her skepticism of Violette’s talk of vampires evolves into an ethical confrontation with her own humanity—can she condemn creatures who act on loneliness when humans themselves exploit and abandon each other? Violette’s existence blurs the moral boundary entirely.

Once a human child and now a hunter of monsters, she occupies a space between guilt and duty, enacting justice through violence while mourning her lost innocence. Nanju’s descent into complicity reflects the fragility of morality under pressure; her crimes arise not from evil intent but from exhaustion and despair.

The vampires themselves are not uniformly demonic—Lily and Greta embody tenderness and restraint, while Ulan represents the corruption of empathy into domination. Through these contrasts, the novel challenges the binary of good and evil, suggesting that monstrosity lies not in supernatural hunger but in the human capacity to rationalize cruelty.

Suyeon’s survival at the end, marked by her hidden bite scars, completes this moral ambiguity—she is both victim and witness, altered by the very darkness she sought to expose. The closing realization that “monsters live quietly beside humankind” encapsulates the story’s ethical vision: humanity is defined not by blood or mortality but by the choices made in the face of suffering, and by whether one still reaches for compassion even when it no longer saves anyone.