Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma Summary and Analysis

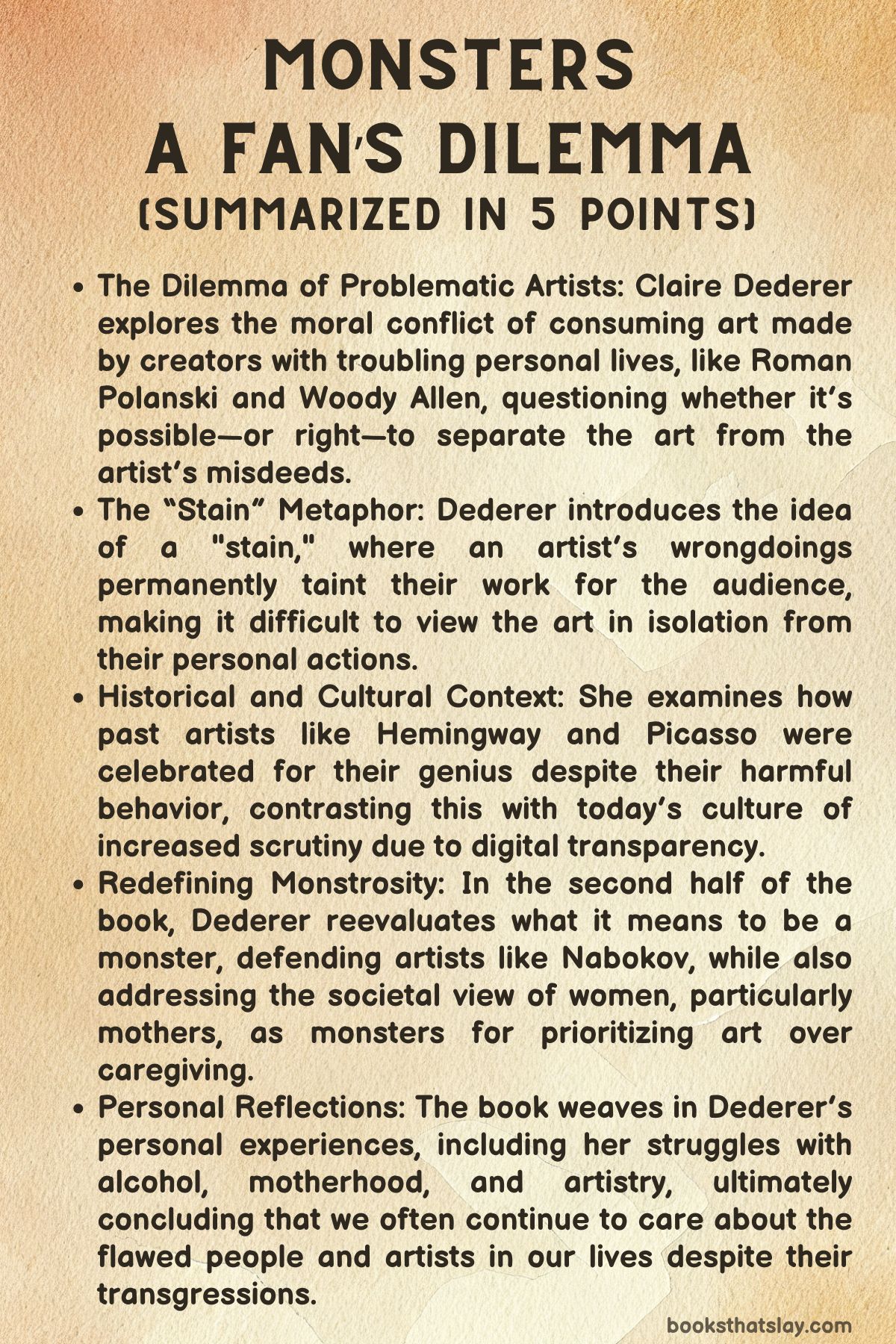

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer is a thought-provoking 2023 book that delves into the moral complexities of engaging with art made by problematic artists. Through a mix of memoir and essays, Dederer explores the conflict between appreciating the work of artists like Roman Polanski, Woody Allen, and Michael Jackson, while grappling with their troubling personal histories.

Drawing from her own experiences as an audience member, she crafts an “autobiography of the audience,” investigating whether we can—or should—separate an artist from their misdeeds, ultimately offering a nuanced meditation on ethics, culture, and personal responsibility.

Summary

In Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, Claire Dederer embarks on a journey to resolve the question: how can we enjoy the art of creators whose personal lives are filled with wrongdoing? Her inquiry begins in 2014, driven by the works of filmmaker Roman Polanski, whose cinematic brilliance is tainted by his sexual assault of an underage girl.

Feeling both captivated by his films and repulsed by his actions, Dederer seeks intellectual clarity on how to handle this paradox but finds scant guidance.

Realizing that logic alone cannot untangle her emotional conflict, she decides to examine the issue through the lens of her personal reactions to art, framing her reflections as an “autobiography of the audience.”

Her exploration deepens as she examines the films of Woody Allen, whose controversial relationship with his adopted stepdaughter, Soon-Yi Previn, shattered Dederer’s long-held admiration for his work.

Like Polanski, Allen’s art forces her to confront an internal dissonance: while Allen’s films once resonated deeply with her, especially Manhattan, his personal life now clouds her appreciation.

She observes how the women in her life share similar discomfort with Allen’s legacy, while the men often dismiss her concerns, urging her to focus solely on the films’ artistic value.

Dederer wonders whether men’s supposed objectivity might be just as emotionally driven as her own reactions.

Dederer then broadens her definition of a “monster” in the art world, identifying them as creators whose actions make it impossible for audiences to view their work without considering their misdeeds.

She explores this “stain” metaphor—where personal behavior taints an artist’s output—through discussions of figures like Michael Jackson, accused of child abuse, and J.K. Rowling, whose controversial views on transgender issues have complicated her relationship with fans.

The digital age, Dederer argues, intensifies this preoccupation with artists’ biographies, as it is nearly impossible to separate art from the person in today’s hyper-connected world.

Looking to the past, Dederer reflects on her 1970s Seattle childhood, when art lovers had to actively seek out information about their heroes.

She contrasts this with earlier eras, when figures like Hemingway and Picasso embraced toxic masculinity, and their violent behavior was seen as part of their genius.

Dederer critiques modern audiences for believing themselves morally superior, arguing that history is littered with problematic artists whose works we continue to admire under the false pretense that they simply “didn’t know better.”

In a shift from her initial premise, Dederer reevaluates the concept of monstrosity. She defends Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita as an artistic risk meant to expose the horrors of pedophilia, suggesting Nabokov is an “anti-monster” who made difficult creative choices to reveal uncomfortable truths.

She also examines the feminist artist Ana Mendieta’s death, allegedly at the hands of her husband, Carl Andre, to question where victims and perpetrators fit into the artistic narrative.

Finally, Dederer turns the spotlight inward, reflecting on women as “monsters” through the lens of motherhood.

She explores how artists like Sylvia Plath and Joni Mitchell sacrificed maternal roles for their work, leading her to wonder whether she has embraced enough “monstrosity” to be a great artist herself.

Through this personal lens, she confronts her own struggles with alcohol and the ways it transformed her, ultimately concluding that, flawed as they may be, we often continue to love the monsters in our lives.

Analysis and Themes

The Conflict Between Aesthetic Merit and Moral Integrity in Art Consumption

Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma grapples with the dissonance between an artist’s moral failings and the aesthetic value of their work. The primary theme of the book centers on the ethical question of how to engage with art created by individuals whose personal actions are morally reprehensible.

Dederer uses figures such as Roman Polanski and Woody Allen as case studies, acknowledging the deep emotional and intellectual pleasure that comes from their art while simultaneously confronting the revulsion elicited by their personal lives. The tension between enjoying the art while knowing the artist’s misdeeds is never fully resolved; instead, Dederer makes clear that this conflict will persist as long as art is entwined with the biography of its creator.

She suggests that the audience’s emotional response is not just a product of the work itself but also of the moral baggage carried by the creator, thus complicating traditional notions of art criticism, which often tries to separate the two. The dilemma here isn’t just about how to engage with art—it’s about whether it’s even possible to do so without implicating oneself in the creator’s wrongs.

The Inextricable Link Between Artistic Genius and Monstrosity

A recurring theme in Monsters is the notion that society has historically conflated artistic genius with moral transgression, particularly in men. Dederer traces the genealogy of this idea back to artists such as Ernest Hemingway and Pablo Picasso, arguing that their mythic status as geniuses was often bolstered by their brutal treatment of women.

The ideal of the tortured, monstrous male genius persists into the present, creating an atmosphere where the artist’s personal flaws are excused or even romanticized as part of their creative identity. Dederer suggests that this cultural attitude perpetuates a dangerous narrative where art is seen as transcending the personal failings of the artist, effectively dehumanizing victims of the artist’s abuse and justifying moral indifference.

This myth of the monstrous genius not only affects how we interpret past artists but also shapes our contemporary interactions with creators who engage in similarly destructive behavior. Dederer questions whether the creative process itself necessitates such monstrosity or whether society has simply constructed a narrative that permits immoral behavior in the name of genius.

The Stain of Personal Biography on Art Reception in the Digital Age

One of the book’s most compelling arguments is the “stain” metaphor, through which Dederer explores how an artist’s personal life irreversibly taints their work. Unlike in previous eras, where the biography of an artist was often obscure or incomplete, the digital age has made the private lives of public figures readily available, resulting in the inescapable context of their actions permeating how audiences consume their art.

Dederer uses J. K. Rowling’s outspoken transphobic views as an example of how a contemporary audience cannot separate her deeply personal beliefs from her work, especially in a culture dominated by social media and digital discourse. The idea of “the stain” suggests that no matter how brilliant a piece of art might be, it cannot be experienced without the shadow of the artist’s personal failings coloring its reception.

This raises a profound question about how modern audiences should navigate the tension between personal biography and artistic output, especially in an era when public personas are so intertwined with the work they produce.

The Gendered Nature of Monstrosity and the Double Standards Imposed on Female Artists

Dederer complicates the concept of monstrosity by examining its gendered dimensions, particularly the way women artists are held to a different standard of moral judgment. In Monsters, she identifies a societal double standard where male artists are often celebrated for their monstrosities, while female artists are condemned for behaviors that deviate from normative expectations, particularly around motherhood and domesticity.

For instance, Dederer points out that the ultimate “female monster” in societal terms is a mother who abandons her children, citing Doris Lessing, Sylvia Plath, and Joni Mitchell as examples. These women’s choices to prioritize their art over their children are framed as monstrous in a way that male artists are rarely judged for their personal transgressions.

Dederer suggests that female artists are often denied the same artistic license afforded to men, forced to balance the competing demands of societal morality and creative freedom in ways that men are not. The theme here extends beyond personal failings; it touches on how deeply embedded gender norms restrict women’s participation in the artistic world, framing their ambition or neglect of traditional roles as monstrous.

The Ethical Complexity of Loving Art Made by Problematic Artists

Dederer ultimately arrives at the paradoxical conclusion that despite all the moral hand-wringing, audiences continue to love the work of problematic artists, even when they cannot condone the artist’s actions. This theme explores the human capacity for cognitive dissonance, where the audience is forced to confront their own complicity in consuming art that they know is linked to monstrous behavior.

Rather than offering a neat resolution, Dederer recognizes that audiences are often willing to tolerate, rationalize, or compartmentalize their discomfort to preserve their connection to the art. In examining her own struggles with alcoholism, Dederer reflects on how coming to terms with her own monstrosity enabled her to view the humanity of other monsters, even those whose actions are much more damaging.

The theme here is not about moral absolution but about accepting the messy, uncomfortable reality of human imperfection—both in the audience and the artist. Art, she suggests, may always be compromised, but so are the humans who make and love it.

The Fallacy of Moral Superiority in Modern Art Consumption

In her exploration of how audiences approach art, Dederer also critiques the modern tendency to view historical artists through the lens of moral superiority.

She argues that contemporary audiences often distance themselves from the problematic behaviors of past artists by assuming that those creators simply did not “know better.”

This sense of moral elevation allows modern viewers to enjoy the art guilt-free, as if they themselves would not have engaged in the same behaviors had they lived in those times.

Dederer deconstructs this idea, suggesting that it is a convenient lie that lets us consume problematic art while feeling morally insulated. She contends that this false sense of progressiveness obscures the more uncomfortable truth: that modern audiences are not fundamentally more enlightened than the artists they judge.

The digital age may have increased the visibility of moral failings, but it has not necessarily made audiences more ethical in their consumption of art.