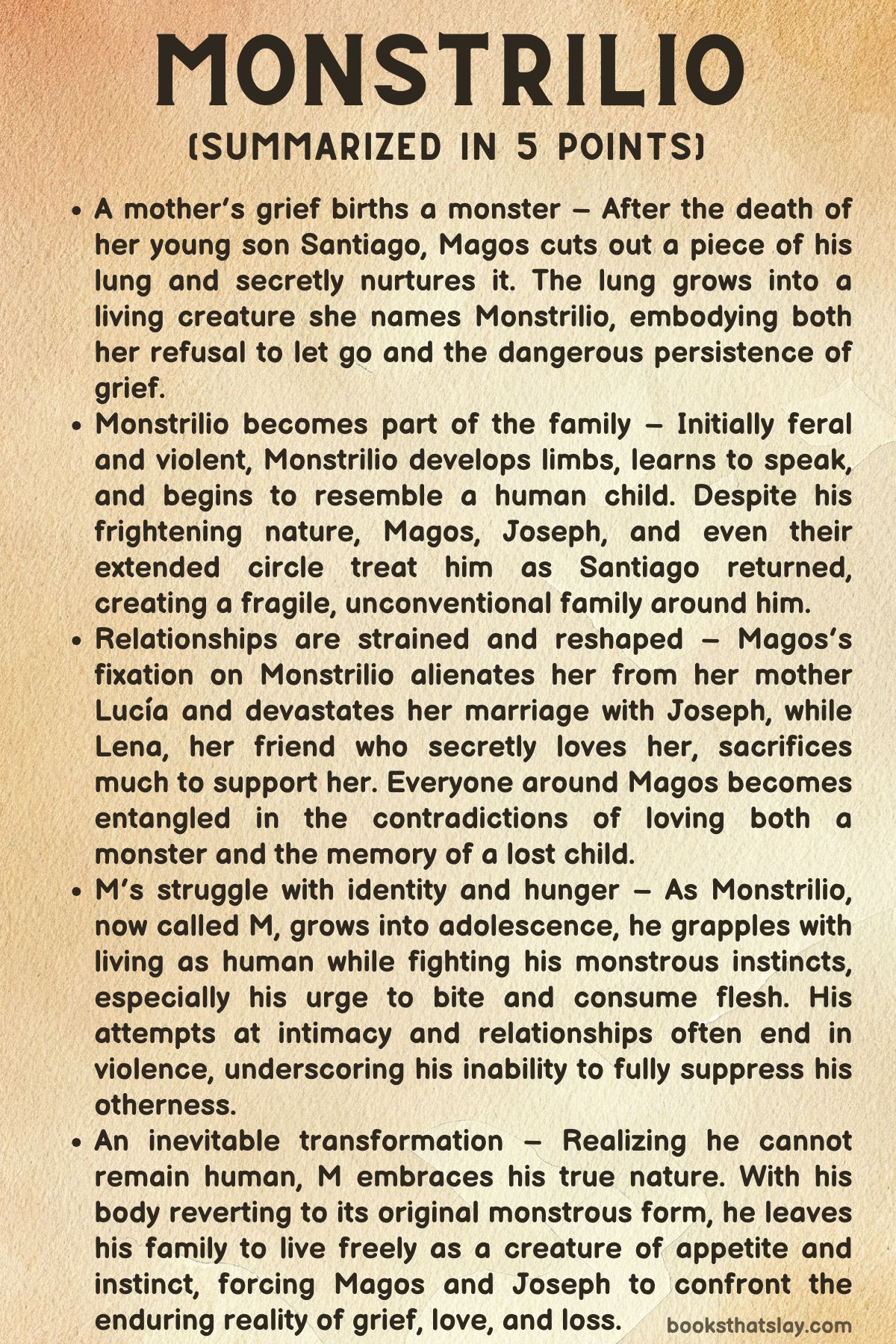

Monstrilio Summary, Characters and Themes

Monstrilio by Gerardo Samano Cordova is a dark and unsettling exploration of grief, love, and the monstrous shapes they can assume.

The novel follows a mother, Magos, who loses her young son Santiago and, in her devastation, cuts out a piece of his lung. This act sparks a disturbing transformation, as the organ evolves into a living creature she names Monstrilio. The story traces how this unnatural being becomes both a mirror of grief and a member of a fractured family, raising questions about identity, love, obsession, and the cost of clinging to the past.

Summary

The story begins in a house in upstate New York, where Magos and her husband Joseph lie next to the body of their dead son Santiago. Magos is overcome not by wailing sorrow but by a muted numbness. While Joseph clings to the body, desperate to hold onto their child in physical form, Magos feels disoriented and hollow. In this quiet devastation, she cuts into Santiago’s body and takes a piece of his lung, a shocking act that will shape the course of everything that follows.

Magos brings the lung back with her to Mexico City, concealing it inside a jar. The lung becomes her private object of grief, a relic and a burden she cannot release. Inspired by folklore told by Jackie, the family housekeeper, Magos begins feeding the lung, and in time, it grows. What begins as a fragment becomes a strange, living creature—feral, grotesque, and hungry. The lung consumes flesh, attacking even the family dog, reminding Magos that it is not Santiago reborn but something entirely different. Despite the danger, she protects and nurtures it, unwilling to sever her connection.

Her life in Mexico becomes increasingly strained. Magos isolates herself, refusing her mother Lucía’s encouragement to rejoin the world or to find solace in ritual and community. Joseph, shattered by grief, grows distant, and their marriage begins to collapse. The lung-creature, now developing form and behavior, demands her attention. Jackie, who offers support, warns her of the danger, but Magos refuses to let go. Eventually, when the lung attacks Lucía, Magos’s secret is revealed to others, including Lena, her former roommate and close friend who harbors romantic feelings for her. Together, they manage to kill the creature, but it reappears weeks later, larger and stronger.

Naming the creature Monstrilio, Magos treats it as both child and otherworldly presence. Monstrilio grows in startling ways, developing limbs, acquiring language, and showing intelligence. Though monstrous, he becomes a point of connection and division among those around Magos. Lena sacrifices much to support her, even at the expense of her own well-being. Joseph, upon discovering Monstrilio, is initially horrified but gradually drawn into the unsettling bond, especially when the creature calls him “Papi.” Monstrilio becomes the strange center of this broken family, embodying both the impossibility of moving forward and the refusal to relinquish grief.

Magos embraces a new identity as an artist, transforming Santiago’s old room into a performance space. Joseph constructs a play area for Monstrilio, and together they form a fragile, patchwork household. Lena, heartbroken by her unrequited love for Magos, eventually accepts her distance but cannot fully detach from the life she imagined. Even Lucía and Jackie, once repulsed, are charmed and unsettled by Monstrilio’s childlike affection, despite his dangerous nature.

Years later, the narrative shifts to the perspective of Joseph, now with a new partner, Peter. Their seemingly normal life is shadowed by Joseph’s unresolved past. Monstrilio, now more human-like and known as M, lives in Berlin with Magos. He is withdrawn, struggling to reconcile his human experiences—work, friendship, and desire—with his monstrous urges, such as biting and consuming. His relationships, especially with a man named Thomas, expose his duality: he craves connection but remains unable to suppress his violent hunger.

Joseph, meanwhile, struggles to balance his life with Peter and his loyalty to M and Magos. When Peter proposes, Joseph accepts, though he hides the truth about M’s origins and their shared history. His double life creates constant tension. This escalates when Magos stages a performance piece called SON in Berlin, mourning Santiago’s death through art. M attends, only to be devastated by the public reminder of who he once was. Unable to reconcile his identity with Magos’s grief, he disappears, leaving Joseph torn between honesty with Peter and loyalty to the son he cannot fully explain.

The later chapters focus on M’s increasing struggle to live as human. He experiments with intimacy, even finding partners who allow him to bite them, but his hunger overwhelms any attempt at normalcy. In one catastrophic encounter with a man named Sam, M crosses the line from controlled desire into lethal violence, consuming him despite his pleas. His family, complicit in covering up the act, is forced to acknowledge the danger he poses.

As M grows older, signs of his original monstrous form reemerge. His arm begins transforming back into a claw-like appendage, and his jaw unhinges, hinting at a return to his primal state. Recognizing that he cannot suppress his true nature, M tells his parents he must leave. Though it devastates them, they allow him to walk into the woods, accepting that his existence cannot be contained within human life.

The novel ends with M embracing his transformation, leaving behind family and human bonds to pursue an unknown future as a creature of appetite and freedom. For Magos, Joseph, and those bound to him, Monstrilio remains the embodiment of their grief—loved, feared, and impossible to control.

In this unsettling narrative, Monstrilio reveals how grief refuses to be neatly resolved, how love can bind itself to what is dangerous, and how identity shifts when the past can never be left behind. It is a meditation on family, desire, and the monstrous forms that loss can take, asking whether acceptance means release or surrender.

Characters

Magos

Magos is the central figure in Monstrilio, a grieving mother whose life becomes defined by the unbearable loss of her young son Santiago. Her grief is not expressed in grand or public gestures but rather through private acts of desperation, culminating in the shocking decision to cut out a piece of her son’s lung after his death.

This action reflects both her inability to let go and her yearning to keep part of him alive, no matter the cost. The lung she nurtures becomes Monstrilio, a creature that represents both her mourning and her refusal to accept finality. Magos’s identity erodes under the weight of grief, leaving her alienated from her husband Joseph and estranged from her mother Lucía. She increasingly directs all her energy into Monstrilio, treating him as a continuation of Santiago rather than recognizing him as something entirely other.

Over time, her obsession becomes both creative and destructive, fueling her new artistic identity while also binding her to a dangerous and uncontrollable being.

Joseph

Joseph is Magos’s husband and Santiago’s father, a man devastated by grief but unable to sustain his marriage in the wake of tragedy. His grief manifests in physical intimacy with his son’s body, clinging and nuzzling as though he could undo death through sheer will.

Unlike Magos, who becomes numb and inwardly consumed, Joseph’s mourning is raw and visceral. As Monstrilio grows, Joseph initially reacts with horror but gradually begins to see in the creature a reflection of Santiago. When Monstrilio calls him “Papi,” Joseph is pulled back into his grief, torn between revulsion and love. His later life with Peter reflects an attempt to move forward, yet the unresolved past continues to shadow him.

Joseph’s divided loyalties—to Peter, to Magos, and to Monstrilio—highlight the impossibility of reconciling past loss with present love. He is a character caught between two lives, perpetually haunted by the secret of his son’s monstrous second existence.

Santiago / Monstrilio / M

Santiago is first introduced as a dead child, his absence the central wound of the narrative. Through Magos’s desperate act, a piece of his lung becomes Monstrilio, a grotesque creature that consumes flesh and grows into a semi-human form.

As Monstrilio develops, he embodies both the hope of Santiago’s return and the monstrous nature of grief itself. Nurtured by Magos, Lena, and Joseph, he evolves into a more human-like figure, eventually known as M. Despite his outward appearance, he struggles with violent cravings, particularly his compulsion to bite and consume flesh.

This duality—human in body, monstrous in instinct—defines his existence. As M matures, he seeks connection, romance, and a sense of belonging, yet his urges sabotage every attempt at normalcy.

His ultimate decision to leave his family and embrace his monstrous nature underscores his inability to fit into human life. M is both victim and danger, a being created out of love and loss, yet doomed to exist outside the boundaries of humanity.

Lucía

Lucía, Magos’s mother, represents an older generation’s response to grief, emphasizing ritual, community, and shared mourning. She urges Magos to embrace practices that might allow others to help carry her burden, but Magos resists, clinging instead to her solitary pain.

Lucía becomes one of the first to see the danger of Monstrilio after he attacks her, yet she also allows herself, in time, to be charmed by his childlike qualities. Her relationship with Magos is strained, reflecting the tension between maternal guidance and a daughter’s autonomy.

Lucía embodies the voice of reason and tradition in the novel, standing in stark contrast to Magos’s obsessive path.

Jackie

Jackie, Lucía’s partner and the family’s longtime housekeeper, plays a subtle yet crucial role in the story.

It is her story of folklore—about a woman who fed a heart until it grew into a man—that sparks Magos’s decision to feed Santiago’s lung. Jackie is compassionate and supportive but also wary of Monstrilio’s danger. Her perspective blends practicality with elements of myth, grounding the novel’s surreal developments in cultural memory.

Jackie’s warnings serve as a counterbalance to Magos’s obsession, though ultimately she too is drawn into the strange family unit that forms around Monstrilio.

Lena

Lena, Magos’s loyal friend and former roommate, brings another dimension of love and longing to the narrative. She harbors deep romantic feelings for Magos, feelings that complicate her willingness to help raise and protect Monstrilio. Lena sacrifices her own comfort, peace, and even her home to support Magos, but her devotion comes at the cost of her own identity and stability.

Her jealousy of Monstrilio reflects both her unfulfilled desire for Magos and her frustration at being sidelined by the grief-driven bond between mother and monster. Despite her heartbreak, Lena remains tied to Magos, embodying the theme of love that persists even when it cannot be fulfilled.

Peter

Peter enters the narrative later, as Joseph’s partner after his marriage to Magos collapses. He represents Joseph’s attempt at normalcy and stability, offering love, companionship, and even marriage.

Yet Peter exists on the margins of Joseph’s hidden past, unaware of Monstrilio’s origins and the unresolved grief that defines Joseph’s identity. His insistence on honesty and openness contrasts sharply with Joseph’s secrecy, and his character highlights the tension between building a future and remaining trapped by the past.

Though less directly involved in the central conflict, Peter is vital in showing the impossibility of compartmentalizing grief when it has transformed into something monstrous.

Uncle Luke

Uncle Luke serves as a caretaker figure for M during his adolescence, providing structure, stories, and a sense of calm. His presence allows M brief moments of comfort and normalcy, as activities like braiding his hair and reading aloud soothe M’s inner turmoil.

Luke’s role may appear secondary, but he embodies the quiet attempts at nurture and acceptance that contrast with Magos’s obsessive love and Joseph’s conflicted attachment. Luke accepts M without judgment, creating a rare pocket of stability in an otherwise chaotic existence.

Themes

Grief as Creation and Refusal of Loss

In Monstrilio, grief is not simply an emotion but an engine that reshapes reality. Magos’s decision to cut out a piece of Santiago’s lung and carry it from upstate New York to Mexico City refracts mourning into action, ritual, and stubborn refusal. The jarred organ first functions as relic and talisman, a private anchor that rejects the expected rites of funeral and public lament.

But when Magos feeds it and it begins to live, grief becomes a maker: it fabricates a creature that answers to an ache rather than to ethics or nature. The attack on the family dog exposes how bereavement, if treated as sovereign, can demand sacrifices from others; Magos’s pain does not inoculate the household from danger. Joseph’s overwhelming sorrow expresses itself physically—clinging to the body of his son—while Magos’s numbness expresses itself as an extreme experiment in keeping something of Santiago near.

These differing responses render grief a centrifugal force that spins the family away from shared ceremonies and toward isolation, secrecy, and improvised rites of feeding and care. As the lung grows into Monstrilio, mourning hardens into a daily routine: hiding, protecting, and explaining the impossible. Even years later, when Monstrilio passes as M and tries to live as human, grief’s original bargain persists; the parents continue to accommodate what cannot be normalized.

The final image of M leaving for the woods is not closure but acknowledgment that some losses cannot be pacified by memorials or replacements. The sorrow that animated the creature cannot bring Santiago back; it can only produce a different life that requires its own painful letting go.

Motherhood, Ownership, and the Ethics of Care

Magos’s motherhood in Monstrilio unfolds as a negotiation between love, possession, and responsibility. She wants to nurture what she has salvaged from death, yet that nurturing risks turning caretaking into control.

By feeding the lung and later protecting Monstrilio, Magos claims a maternal right over a being that is not her child, even as she addresses him as if he were. The novel scrutinizes the line between caregiving and ownership: how far may a parent go to sustain a bond, and who pays the cost when that bond overrides the safety of others? This tension is staged through the household’s women—Lucía, Jackie, Lena—who serve as voices of caution, accomplices out of loyalty, and sometimes targets of the creature’s volatility.

Their participation complicates the moral ledger: community can cushion grief, but it can also spread complicity. Joseph’s fatherhood adds another layer. When Monstrilio calls him Papi, paternal tenderness ignites even as alarm persists; love is real, but so is danger.

Later, when M kills Sam, the family’s ethic of protection crosses into cover-up, dramatizing how care can become a shield for harm. The book asks whether parental duty includes the courage to release what endangers the world, even if that release feels like another death. Magos’s later turn to performance art does not cancel her maternal impulse; it reroutes it into staging and meaning-making.

Motherhood is portrayed as both sanctuary and hazard, a place where devotion can blur consent and where nurture without boundaries can curdle into a claim over another’s being. The final permission granted to M—to leave and live as creature—becomes a hard-won version of care that refuses ownership at last.

Monstrosity, the Body, and Appetite

Bodies in Monstrilio are sites of truth. The lung’s appetite inaugurates a world where hunger is literal, messy, and morally destabilizing.

As Monstrilio grows, desire and consumption knit together; he learns language and affection while retaining the urge to bite, to taste, to eat. When M engages in erotic play that includes biting Thomas, the novel treats appetite as a spectrum that runs from intimacy to predation. The body announces limits that social scripts cannot fully manage. Biting can be negotiated, even eroticized, but the same instinct can snap past consent when hunger floods the scene.

Sam’s death is the most severe articulation of this risk; M’s inability to stop eating once begged to stop reveals a terrifying asymmetry between desire and self-governance. The regrowth of the arm-tail, the unhinging jaw, the sense of claws returning—all point to a physiology that refuses the fiction of complete human assimilation.

The body keeps the score of origin and remains a record of what the family has tried to edit. At the same time, the novel resists reducing monstrosity to pure evil. Appetite is not demonized outright; it is presented as a fact that demands responsible forms. The problem arises when an inner urge is granted priority over another’s life.

By staging this conflict through flesh and teeth rather than abstract moralizing, Monstrilio grounds its ethics in sensation: hunger, taste, pain, relief. The ending acknowledges that some bodies cannot be domesticated without violence to themselves or others. Recognizing that truth becomes an act of mercy, not a capitulation to horror.

Queerness, Desire, and the Making of a Self

Queerness in Monstrilio is not only about who loves whom; it is about how a self is constructed under pressures of secrecy, difference, and longing for belonging. M’s adolescence in Berlin involves first jobs, friendships, and sexual discovery, yet every step toward intimacy is shadowed by his history as a creature born from grief.

Consent-focused encounters that center biting show an earnest attempt to craft a livable sexuality from impulses others might reject. These scenes explore the possibility that desire can be negotiated at the edge of danger, where clarity, communication, and aftercare are essential. The tragedy with Sam demonstrates the fragility of those negotiations when appetite, shame, or euphoria overrides the rules that make risk tolerable.

Alongside M’s path, Joseph’s relationship with Peter introduces a different queer strand: the strain of hiding a past that cannot be spoken in ordinary terms. Engagement announcements and domestic routines clash with the unshared truth about M’s origin, and secrecy erodes trust long before any revelation occurs.

The novel suggests that queer kinship can be generous and adaptable—uncle Luke’s caretaking, Lena’s devotion, the patchwork household around Monstrilio—but it also shows how concealment corrodes the very intimacy it seeks to protect. Queerness here becomes a laboratory for chosen family, negotiated desire, and identity-making; it refuses normalizing arcs that promise easy assimilation. M’s decision to leave is not self-hatred but self-definition, a choice to inhabit a form of life that standard categories cannot house.

The resulting picture is neither tragedy nor triumph alone; it is a complicated freedom that respects difference without erasing responsibility for others.

Art, Performance, and the Politics of Mourning

Magos’s turn to art reframes grief as something that can be staged, witnessed, and circulated. In Monstrilio, creative practice offers structure when life feels ungovernable, but it also risks converting private pain into public spectacle.

The performance piece SON honors Santiago and gives Magos a language beyond caretaking and secrecy; it allows her to narrate loss on her own terms. Yet the presence of M in the audience exposes an ethical fault line. If the creature was born from Magos’s refusal to accept death, what does it mean to craft art that mourns the original child while the second life sits nearby, absorbing the message that he is not the one being grieved?

The ovation at the end of SON highlights art’s double edge: validation for the artist and possible injury to those embedded in the story. Joseph experiences the work as a betrayal, a public claim that displaces the living being who has carried their shared history.

The book does not condemn Magos’s art; it interrogates the costs of turning memory into performance, especially when the audience’s catharsis might deepen another’s confusion or shame. At the same time, art functions as a survival technology.

By transforming Santiago’s room into a studio, Magos reclaims space and authorship, refusing to be only mother or mourner. Monstrilio therefore presents art as both remedy and hazard: it can organize chaos and create community around meaning, but it can also aestheticize pain and unsettle those who are conscripted into the narrative.

The ethical question becomes not whether to make art from loss, but how to do so without sacrificing the living to the needs of the work.

Secrecy, Complicity, and Moral Gray Zones

From the hidden jar in Mexico City to the quiet disposal after Sam’s death, Monstrilio is saturated with silence as strategy.

Secrets shield the family from legal consequence and social exile, but they also bind them together in a pact that distorts every relationship. Joseph’s withholding from Peter is only one example; Lena’s lifelong devotion, Jackie’s warnings, and Lucía’s attempts at equilibrium all orbit the unspoken truth that the household exists because a boundary was crossed at a morgue table years ago. Secrecy is initially framed as protection—of Magos’s sanity, of Monstrilio’s chance to live—but over time it evolves into a system of debt.

Each participant owes the others continued silence, and that debt becomes the real glue of the family. Complicity grows in increments: feeding the lung, hiding an attack, lying to a partner, cleaning a scene. The book asks readers to examine how good intentions can congeal into a harmful order, not by sudden malice but by cumulative accommodation. Yet the narrative resists a simple moral verdict. The same secrecy that endangers the community also keeps a vulnerable being alive long enough to make his own choice about his future.

The family’s cover-up is condemnable and understandable at once; this tension is the novel’s moral temperature. In the end, the most honest act is spoken permission: letting M walk away. Secrecy maintained the family; truth breaks the pact without erasing love. The gray zones remain, but the story locates a difficult integrity in surrendering control and accepting consequences that cannot be managed in private forever.

Transformation, Identity, and the Limits of the Human

Across its arc, Monstrilio maps a metamorphosis that refuses neat assimilation. Organ to creature, creature to boy, boy to M, and finally M to something beyond human designation—each stage carries forward traces of the last. Language and manners arrive, but appetite lingers.

Domestic routines normalize the household, yet the body reasserts its difference with the reemerging arm-tail and widening jaw. The novel uses these shifts to challenge a cultural reflex that equates humanity with safety and monstrosity with moral failure. M is capable of tenderness, curiosity, and loyalty; he is also capable of lethal harm. Rather than sorting him into fixed categories, the story insists on a restless identity that changes with context and choice.

Transformation is not treated as cure but as unfolding. Joseph’s own identity evolves, too, as he tries to become a partner to Peter while remaining a father to someone who cannot be introduced at dinner. Magos evolves from clandestine caretaker to artist willing to risk public scrutiny. Even the cityscapes—upstate New York, Mexico City, Berlin—serve as stages where identity is tested under different pressures of language, law, and community.

The closing decision to walk into the woods is less escape than alignment with a truth that has always been present. It acknowledges that some beings cannot be fully themselves inside the terms of the human household. The family’s assent signals growth on their part as well: identity is honored not when it is successfully masked, but when it is given room to exist, even if that existence takes it beyond the family’s reach.