Mood Machine by Liz Pelly Summary and Analysis

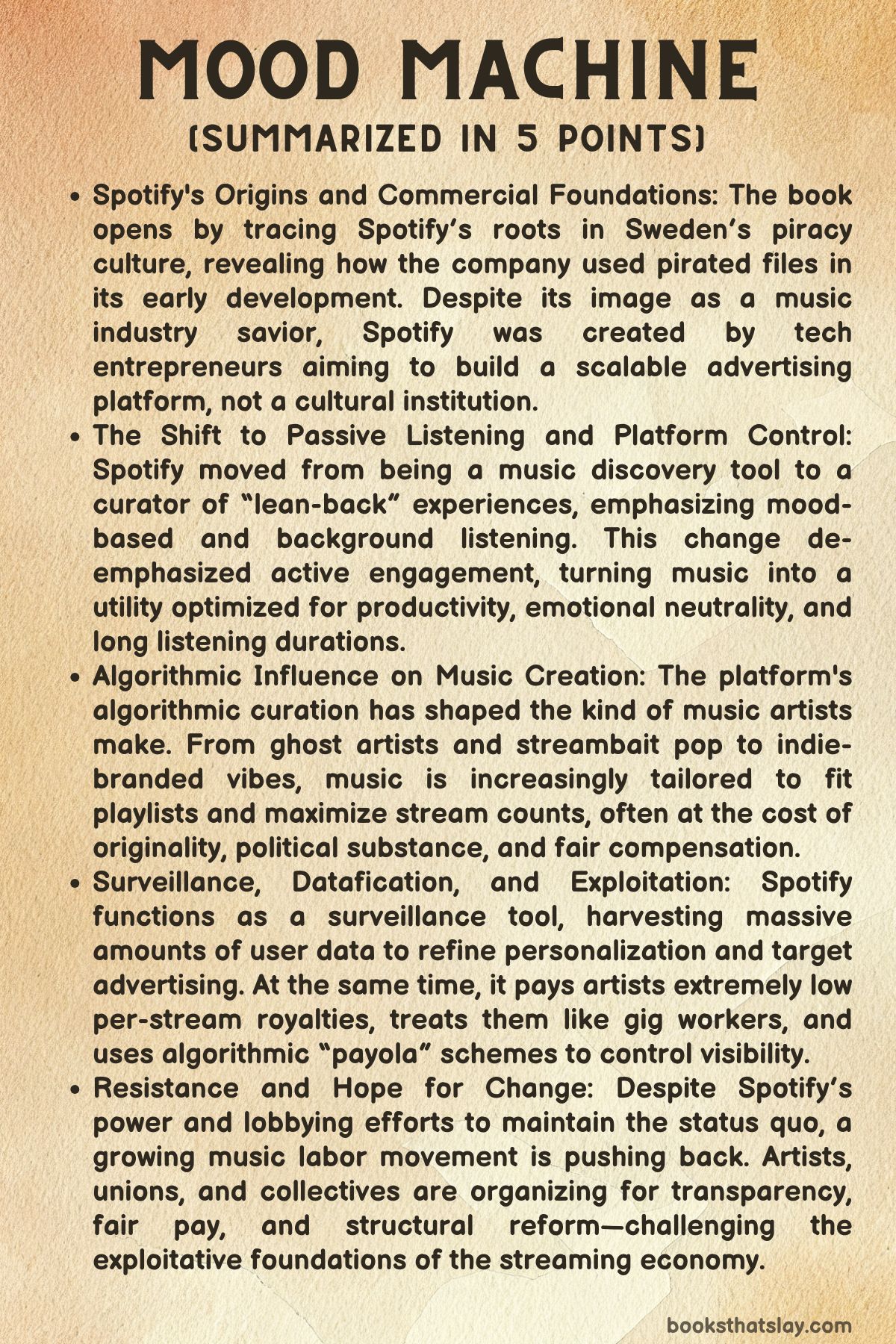

Liz Pelly’s Mood Machine is a scathing and illuminating critique of the modern music streaming industry, centered on the evolution of Spotify from a piracy-era response into a dominant force that redefines not just how we listen to music, but how music is created, marketed, and valued. With incisive detail and journalistic clarity, Pelly explores the commodification of mood, the erosion of independent artistry, and the rise of platform capitalism.

At the heart of the book is the tension between artistic expression and data-driven manipulation—between music as culture and music as content. Through case studies, historical parallels, and interviews with musicians and industry insiders, Mood Machine reveals how the playlist economy and mood-driven algorithmic curation have reshaped the soundscape of our everyday lives.

Summary

Mood Machine begins by tracing the digital and political roots of Spotify’s rise in Sweden in the early 2000s, following a period of cultural upheaval marked by the anti-globalization protests in Gothenburg. The failure of traditional activism led to new forms of cultural resistance, such as fare strikes and the founding of Piratbyrån—a group advocating free information and cultural sharing.

From this, The Pirate Bay was born, which fundamentally disrupted the music industry and pushed record labels into disarray. Spotify emerged in this context, not as a savior of music culture, but as a business opportunity grounded in advertising and frictionless access.

Its founders were more interested in monetizing attention than supporting artists, and Spotify’s early versions reportedly used pirated music files to prototype its model.

The platform’s strategy was to mimic the immediacy and convenience of piracy while packaging it within a legal and polished user interface. This design was crucial to attracting major record labels, who were initially skeptical.

Spotify offered them equity, large advances, and minimum payouts in exchange for licensing deals. This resulted in a tiered system that gave major labels and their artists preferential treatment, reinforcing the industry’s inequalities rather than democratizing access as it claimed.

A critical part of Spotify’s success was the introduction of mood-based playlists—categories like “Chill Vibes,” “Peaceful Piano,” and “Deep Focus”—which shifted the center of music consumption away from albums, artists, or even genres, toward emotional and situational use cases. This repackaging of music into ambient and functional categories coincided with a broader societal trend toward optimization and productivity.

The playlists were curated not to provoke thought or elicit strong emotional reactions, but to accompany passive activities like studying, commuting, or sleeping.

This model echoes historical attempts to control mood through music, including Muzak in mid-20th-century factories and Edison’s early 20th-century catalogs promising “mood music. ” What was once considered background music for elevators or waiting rooms was rebranded and refined by Spotify’s algorithms into a dominant mode of cultural consumption.

The result was the rise of “functional music”—songs that serve a utilitarian purpose rather than invite creative engagement.

The impact on musicians was immediate and far-reaching. Independent artists, once able to find niche audiences online, found themselves trapped in a system that rewarded algorithmic friendliness over artistic innovation.

Lo-fi music, once a grassroots genre born of sampling and experimentation, became sanitized and commodified. Brands like Lofi Girl dominated the genre, turning it into a genre-less background blur of interchangeable beats, devoid of identity or narrative.

Spotify’s in-house and partner curators quietly seeded these playlists with stock music made by ghost artists—often underpaid musicians working under contract who received flat fees with little or no recognition or residuals. Internally, Spotify called this “perfect fit content,” and these tracks were engineered to seamlessly blend into playlist themes without standing out.

This trend blurred the line between real and synthetic, between art and product. Swedish production houses like Firefly and Epidemic Sound supplied Spotify with massive quantities of anonymous, inexpensive content optimized for playlists.

By doing so, they undercut artists producing more substantive work while contributing to the aesthetic flattening of the music ecosystem. Ambient and experimental genres that once thrived on specificity and context were reduced to generic, frictionless soundtracks for tasks.

Spotify’s embrace of AI music generation and biometric data took this commodification further. The platform’s partnerships with startups like Endel explored how AI could produce endless streams of mood music using user data, environmental cues, and emotion-detection algorithms.

Spotify’s abandoned “Soundscape” initiative was an example of their ambitions to provide users with one-button, mood-matching audio streams. These services marketed themselves as therapeutic or productivity-enhancing, often citing dubious scientific studies.

Meanwhile, the underlying model harvested immense amounts of personal data—from skip rates to listening contexts—and sold these insights to advertisers.

The surveillance implications of this model were significant. Spotify didn’t just sell ad space—it sold emotional and behavioral profiles.

Through third-party data brokers, the company tagged users as “Mindfulness_Seekers” or “Captain Morgan Drinkers,” allowing advertisers to target them with uncanny precision. In more extreme cases, Spotify partnered with neuromarketing firms and tested wearable brainwave-scanning devices to “prove” the emotional efficacy of ads—an example of how deeply the company was willing to commodify human attention.

These practices eventually led to legal challenges in the EU under GDPR, but the fines did little to change the system’s core logic.

As the platform matured, Spotify promoted a narrative of empowerment through its artist tools. “Spotify for Artists” and promotional tools like Discovery Mode promised musicians more control.

However, the reality was bleak. Discovery Mode allowed artists to increase their algorithmic exposure in exchange for lower royalty rates—essentially a legalized form of payola.

The system prioritized engagement metrics over artistic merit, and major labels dominated top playlists through preferential treatment and backend agreements hidden by NDAs.

One case study highlighted in the book is that of Lance Allen, an independent guitarist whose career was initially boosted by placements on playlists like “Peaceful Guitar. ” But as Spotify shifted toward cheaper, pseudonymous tracks and “perfect fit” music, Allen found his revenue dropping dramatically.

His story exemplified the volatility of success under Spotify’s model and the illusion of sustainable DIY careers.

Despite the odds, resistance emerged. Musician advocacy groups like United Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW) and the Music Workers Alliance (MWA) began calling for transparency, higher per-stream royalties, and legal reform.

UMAW’s “Justice at Spotify” campaign demanded a penny per stream and helped inspire the Living Wage for Musicians Act in the U. S. Congress. These movements aim to rebuild the music economy around fairness, dignity, and artist rights rather than surveillance and corporate control.

By the end of Mood Machine, Pelly makes it clear that Spotify’s greatest triumph is not in bringing music to the masses but in transforming music into a data product—one optimized for mood, stripped of context, and designed to maximize ad revenue. The idea of “chill” is no longer a subversive rejection of capitalist urgency, but a commercial strategy used to lull listeners into passive consumption.

What’s lost is the soul of music: its messiness, its specificity, its ability to disrupt, provoke, and inspire.

Mood Machine offers a necessary and unflinching look at the consequences of frictionless culture. It is both a historical reckoning and a call to rethink how we value music—not as an ambient backdrop to productivity, but as a vital force of expression, identity, and community.

Key People

Daniel Ek

Daniel Ek, co-founder of Spotify, emerges in Mood Machine not as a music lover or cultural visionary, but as a pragmatic entrepreneur driven by advertising potential and platform efficiency. His decision to enter the music industry was not rooted in artistic passion but in identifying music as a fertile space for disruption due to rampant piracy and inefficiencies.

Ek’s approach reflected a deep alignment with platform capitalism—emphasizing scalability, data optimization, and monetization. He represents a new breed of tech executive who sees culture not as an expressive force but as a malleable commodity that can be engineered and distributed for maximum engagement.

Ek’s actions, from courting major labels with equity deals to investing in AI-generated content, exemplify a technocratic ideology that prioritizes shareholder value over cultural integrity. His dispassionate treatment of music—framing it as a medium for background noise, user profiling, and ad targeting—positions him as both a creator and symptom of the devaluation of artistry in the streaming age.

Lance Allen

Lance Allen, a self-releasing guitarist who found fleeting success through Spotify playlists like “Peaceful Guitar,” embodies the paradoxes of the so-called “independent” artist in the streaming era. Initially presented as a DIY success story, Allen’s career highlights how Spotify’s playlist culture created a temporary ladder for some artists—only to pull it away when corporate logic demanded cheaper, more controllable alternatives.

His willingness to engage with playlist pitching and metadata optimization shows a shrewd adaptation to the platform’s game-like structure, yet his later marginalization by stock music and ghost artists reveals the brutal precarity at the heart of this system. Allen’s trajectory is not one of failure, but of disposability—his relevance and success were contingent on serving Spotify’s needs, and once his content became more expensive or less algorithmically useful, he was quietly replaced.

Through Allen, the book illustrates how streaming’s illusion of independence is often just another form of dependency, marked by instability and invisibility.

Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo

Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo, an activist and scholar, appears as a powerful voice of critique against the racialized and exploitative tendencies of AI-generated music and platform capitalism. Her analysis of projects like FN Meka—a virtual rapper constructed through racist tropes—highlights how digital spaces can replicate and even amplify the worst aspects of cultural appropriation.

Enongo frames AI-generated content as a modern form of minstrelsy, where the aesthetics of Black culture are mined for profit while Black creators are excluded from ownership and visibility. She challenges the idea that technology is neutral, exposing how algorithms, avatars, and machine learning tools are often weaponized to reinforce existing hierarchies.

Her presence in the text provides a moral and ethical framework that counters the cold instrumentalism of Spotify executives. Enongo becomes a conduit for broader conversations about consent, authorship, and the cultural stakes of automation—reminding readers that what’s at risk is not just fair pay, but the soul of music itself.

The Ghost Artists (Perfect Fit Content Producers)

The anonymous musicians behind Spotify’s “perfect fit content” (PFC) represent a new underclass of invisible laborers in the streaming economy. These artists, often hired under contract to create mood-optimized, royalty-light tracks, are stripped of authorship, branding, and agency.

Their music populates top playlists not because of quality or demand but because it is cheap, compliant, and easily slotted into algorithmic formulas. These ghost producers reflect a disturbing turn in music production where artistry becomes indistinguishable from stock audio—tailored to minimize disruption, emotional friction, or cost.

Though they are real musicians, their anonymity and lack of residuals place them closer to gig workers than creators. The character of the ghost artist illustrates how Spotify’s model thrives on erasure: erasing personality, history, and identity from sound in order to render it frictionless and profitable.

In them, the platform finds its ideal contributor—unseen, uncredited, and underpaid.

The Pirate Bay Collective / Piratbyrån

The members of Piratbyrån and the Pirate Bay, though not foregrounded as individuals, function collectively as ideological foils to Spotify’s corporate model. Originating from Sweden’s post-Gothenburg protest culture, they represent a countercultural vision of digital sharing rooted in community, anti-capitalism, and open access.

Their creation of The Pirate Bay was both a technical feat and a political act—a rebellion against the commodification of culture and the legal stranglehold of copyright regimes. In contrast to Spotify’s logic of surveillance and monetization, the Pirate Bay ethos celebrated chaos, decentralization, and cultural abundance.

The tension between this anarchic digital underground and the sanitized, corporatized world of streaming platforms reflects a broader shift from digital utopianism to digital enclosure. As the book unfolds, the Pirate Bay figures—activists, hackers, punks—serve as ghosts haunting Spotify’s gleaming interface, reminders of a moment when the internet promised freedom, not frictionless exploitation.

UMAW and Music Workers Alliance (MWA)

Though not personified through single characters, the collective actions of groups like the United Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW) and the Music Workers Alliance (MWA) provide the most tangible forms of resistance in Mood Machine. These organizations are portrayed as organizing forces pushing back against Spotify’s exploitative royalty models and opaque data practices.

Their campaigns—such as Justice at Spotify and advocacy for the Living Wage for Musicians Act—mark a turning point where artists begin to reassert their value not just as content providers but as laborers demanding fair treatment. Unlike the symbolic gestures of branding or “artist-first” messaging promoted by Spotify, these groups operate with material demands, political strategies, and community solidarity.

They are critical characters in the book’s closing arguments, offering a glimmer of hope that collective action can disrupt the data-driven marketplace and restore dignity to creative labor.

Analysis of Spotify as a Character

In Mood Machine, Spotify itself functions as a character—an omnipresent, algorithmic force that shapes not only musical consumption but also labor, identity, and emotional experience. The platform is personified through its decisions, algorithms, interfaces, and curated moods, becoming an invisible conductor of everyday life.

Its core personality traits—efficiency, smoothness, surveillance, and profit-seeking—play out in how it guides user behavior and restructures artistic production. The book does not depict Spotify as malicious per se, but as an inevitable manifestation of platform capitalism, where culture becomes code and value becomes data.

Its chilling effect on musical depth, human connection, and artistic risk reveals a character driven by control masked as convenience. In this light, Spotify becomes both antagonist and infrastructure, an unseen puppeteer whose influence permeates every aspect of the contemporary music ecosystem.

Themes

Mood as a Tool of Control

Mood categorization on Spotify might appear to be a user-friendly feature at first glance, but in Mood Machine, Liz Pelly reveals it as a subtle mechanism of behavioral control rooted in a long legacy of manipulation through music. The book draws direct lines between Spotify’s algorithmic playlisting and earlier corporate or militaristic uses of mood music—such as Muzak in factories or wartime productivity schemes—where the primary goal wasn’t artistic fulfillment but efficiency, docility, and focus.

Through playlists like “Peaceful Piano” and “Lo-Fi Chill,” Spotify doesn’t merely offer options for listeners but nudges them into predictable, repetitive listening habits designed to maximize engagement while minimizing emotional disruption. These emotionally sanitized environments serve corporate interests far more than artistic ones, muting the possibility of music to challenge, provoke, or even deeply move.

Listeners are subtly encouraged to self-regulate their moods not through introspection or social interaction but through passive listening, which often aligns with capitalist ideals of productivity and wellness. This restructuring of music around mood not only disempowers artists by stripping context from their work but also reduces listeners to emotional consumers constantly soothing themselves to remain functional within the pressures of late capitalism.

The deployment of music as mood management—rather than cultural communication—signals a broader shift in how emotional life is mediated by platforms seeking data and monetizable habits rather than artistic engagement.

Erosion of Artistic Identity

In an ecosystem dominated by algorithmically generated mood playlists and corporate curation, individual artistic identity becomes expendable. Mood Machine underscores how Spotify’s shift from album-oriented listening to mood-based playlists results in artists being anonymized and depersonalized.

Tracks are selected not for who made them or what they mean, but for how they fit an algorithmic vibe. This move is exemplified by the rise of pseudonymous stock music and “perfect fit content” (PFC) crafted by unknown or contracted producers who receive flat fees or discounted royalties.

The platform privileges tracks that won’t disrupt the listening flow—short, wordless, tonally neutral compositions devoid of cultural specificity or personality. The result is that musicians are reduced to background workers in their own field, producing content to fill digital shelves rather than sharing meaningful expressions of self or society.

Even genres with strong historical roots in individuality and experimentation—like ambient, lo-fi, and jazz—are repurposed into standardized templates. Platforms benefit from stripping identity because nameless, frictionless music drives repeat listens and consistent engagement.

This undermines the social and cultural function of the artist and redefines music as filler rather than expression. In this world, the idea of a musician as a storyteller, provocateur, or community voice is overwritten by a new definition: someone who delivers calming sound in an efficient, unbranded format.

Exploitation Through Platform Capitalism

Pelly demonstrates that Spotify functions not simply as a music distributor, but as a platform capitalist enterprise that treats both users and artists as sources of data and profit. Its royalty model, based on total platform stream share, naturally privileges the most popular content and undermines niche or independent artists, regardless of their engagement or merit.

The platform’s monetization strategies—like Discovery Mode, where artists can pay with reduced royalties in exchange for increased visibility—are framed as opportunities but more accurately resemble digital payola. These tools create a rigged system in which success requires not just talent but a capacity to navigate opaque algorithms and invest in self-promotion with little promise of equitable return.

Meanwhile, Spotify collects immense amounts of user data, including emotional profiles and listening behaviors, which it packages and sells to advertisers. The listener becomes a product, the artist becomes a contractor, and the platform acts as the sole arbiter of access and value.

This model reflects the broader dynamics of platform capitalism: centralization of power, opacity in operations, and a commodification of human creativity and emotional life. The company’s lobbying efforts and political positioning are not just about music but about entrenching itself as an indispensable infrastructure in cultural life—an infrastructure built on the backs of underpaid artists and unaware consumers.

Devaluation of Listening Itself

One of the most incisive critiques in Mood Machine is its exploration of how Spotify has reshaped not only what we listen to, but how we listen. The platform’s frictionless design—endless autoplay, autoplay-enabled playlists, and algorithmic personalization—discourages active listening and encourages music consumption as a background activity.

This design mirrors the goals of engagement-based social media, where time spent and attention captured are more valuable than thoughtful interaction. Over time, listeners become conditioned to expect music to be soothing, seamless, and undemanding.

This passive consumption redefines the act of listening from a conscious choice into a behavioral reflex, one that often aligns with the pursuit of comfort or productivity. The platform optimizes for continuous play rather than meaningful engagement, reinforcing a mode of listening that diminishes surprise, challenge, or emotional complexity.

Music, once an expressive art form meant to be experienced and interpreted, is reduced to an environmental utility. The deeper danger is that this shift not only changes music’s social function but gradually rewires how people relate to sound and emotion.

The platform’s success rests not just on its catalog or playlists, but on this fundamental reprogramming of listener behavior, which over time erodes music’s cultural depth and replaces it with a data-driven sense of emotional regulation.

Disintegration of the Independent Music Ethos

By closely following the trajectory of independent artists like Lance Allen, Pelly outlines how Spotify has co-opted and ultimately hollowed out the promise of musical independence. Once celebrated as a platform where DIY artists could bypass industry gatekeepers and reach audiences directly, Spotify now operates in ways that replicate—and sometimes worsen—the same power imbalances it claimed to disrupt.

Independent artists are encouraged to behave like entrepreneurs in a marketplace, constantly releasing content, managing campaigns, and adapting their sound to fit platform trends. The music itself becomes secondary to its performance in algorithmic environments.

Even platforms and distributors that began as independent—like AWAL and TuneCore—have been absorbed into major label infrastructures, serving as scouting tools rather than tools of empowerment. The term “indie” is thus emptied of meaning, encompassing both global pop stars and unknown bedroom producers, blurring important distinctions and dissolving community-oriented identities.

This shift signals not only a transformation of market structures but also a cultural erasure. The independent spirit of resistance, experimentation, and community-building is replaced by a metrics-driven hustle.

Spotify’s branding of independence is ultimately a simulation, providing the illusion of opportunity while systemically privileging the interests of corporations and investors. What remains is not an ecosystem of diverse, autonomous voices but a content mill optimized for volume, efficiency, and commercial predictability.