Mother, Nature by Jedidiah Jenkins Summary and Analysis

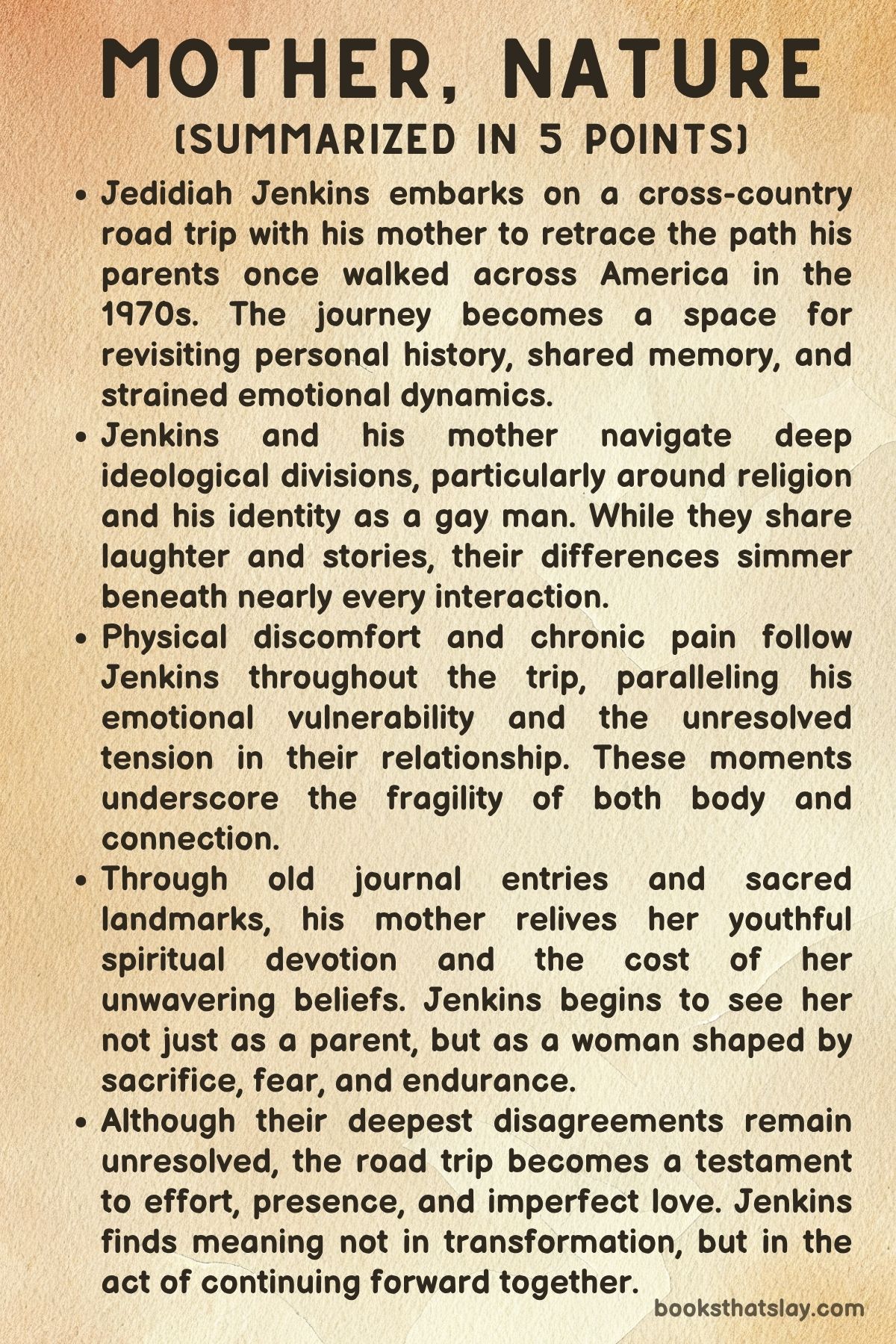

Mother, Nature by Jedidiah Jenkins is a reflective memoir that chronicles a deeply personal road trip between Jedidiah Jenkins and his mother. Jenkins, a gay man and progressive thinker, embarks on a cross-country journey with his devoutly Christian mother to retrace the steps of a historic walk she took with her husband in the 1970s.

Along the way, they confront the ideological, emotional, and spiritual rifts that have long defined their relationship. Jenkins uses the open road as a setting to explore identity, love, faith, and the complicated ties between parent and child.

The book is both travel narrative and emotional excavation, filled with candid dialogue, tension, humor, and moments of deep humanity.

Summary

Mother, Nature begins with a metaphor that sets the emotional tone: the parable of blind monks touching different parts of an elephant, each convinced of a partial truth. This idea of limited understanding frames Jedidiah Jenkins’ complex relationship with his mother, a woman deeply committed to her Christian faith and unable to reconcile her beliefs with her son’s sexuality.

The story kicks off with a memory from 2003—a traumatic car accident that momentarily closes the emotional distance between them. From there, Jenkins proposes a road trip: retracing the steps of the iconic walk his parents took across America decades earlier, hoping to create space for reconnection.

Their journey begins in her eccentric SUV, stocked with colloidal silver, candy, and conservative radio, while Jenkins brings skepticism and quiet hope. The first leg takes them to New Orleans, bypassing scenic stops in favor of familiar comforts.

Jenkins is both amused and agitated by her quirks—her obsession with true crime, her prayers, her firm grip on certainty. Amid cultural and generational divides, they find moments of shared laughter, like bonding over a podcast about D.B. Cooper.

Physical pain shadows Jenkins throughout the trip, a mysterious and chronic abdominal issue that echoes the emotional weight he carries. Despite visits to hospitals and past diagnoses, the pain lingers without clarity.

As they move through Southern towns steeped in his mother’s memories—from wedding chapels to seminary halls—the contrast between their inner worlds becomes sharper. Her stories about the past feel sacred to her, but for Jenkins, they highlight unspoken grief.

She narrates her past, but avoids truly engaging with his present. In Texas and Oklahoma, the journey deepens.

Jenkins sees in his mother a woman shaped by discipline and divine mission, someone who sacrificed autonomy for obedience to faith. Tornado-swept towns and abandoned highways serve as landscapes not only of decay but of introspection.

Jenkins ponders the cost of her belief system—not just for him, but for her. She recites scripture to explain tragedy; he sees climate change and social dysfunction.

Still, the journey binds them—through laughter, routines, and ghost stories. Amarillo becomes a metaphor for their emotional stalemate: wide, barren, unyielding.

The Rocky Mountains bring fresh beauty and deeper tension. Jenkins, aching from physical pain and emotional yearning, asks his mother a question he’s long carried: Would she attend his wedding if he marries a man?

Her evasive, spiritualized non-answer cuts deep. Yet, rather than react in anger, he accepts the moment as part of their reality.

Her love is real but filtered through a worldview that limits her expression of acceptance. Later, when she anoints him with oil and prays over his pain, the gesture feels surreal but sincere.

This is how she loves: through ritual, conviction, and a desire to protect, even if she cannot fully affirm. The final destination is Florence, Oregon, where Jenkins’ parents ended their walk in the 1970s.

Standing at the Pacific, his mother reflects on the price she paid to follow her husband—both the glory and the cost. Jenkins watches her with a mix of admiration and sorrow.

She remains unchanged in theology, but now seen with deeper empathy. They speak of aging, death, and legacy.

Jenkins accepts that he may never receive the full embrace he longs for, but he finds solace in their shared effort to stay in each other’s lives. The road trip doesn’t resolve their differences, but it reaffirms their bond—imperfect, enduring, and unmistakably real.

Key People in the Memoir

Jedidiah Jenkins

Jedidiah Jenkins serves as both the narrator and emotional compass of the memoir. A gay man in his forties raised in a deeply religious Southern Christian household, he is a seeker—of truth, of belonging, of peace with his past.

Throughout the journey chronicled in the book, Jenkins brings a reflective and often conflicted perspective, shaped by his experiences growing up under the weight of religious expectations that clashed with his identity. His internal landscape is one of simultaneous reverence for the love he’s received from his mother and deep pain from her inability to affirm his sexuality.

The physical road trip becomes a vehicle for internal reckoning as Jenkins attempts to bridge the emotional and ideological chasm between them. He is vulnerable, witty, and fiercely introspective, unafraid to examine his own flaws and contradictions.

Despite the hurt, Jenkins does not seek to demonize his mother. Instead, he attempts to understand her—and by extension, himself—more deeply.

His physical ailments, particularly the unexplained abdominal pain, act as a metaphor for the psychological burdens he carries, especially the wound of not being fully seen or accepted by someone he loves so dearly. Jenkins evolves across the memoir, not necessarily by arriving at resolution, but by arriving at clarity—grasping the shape of love that is real, if not ideal.

Barbara Jenkins (Jedidiah’s Mother)

Barbara Jenkins is a vivid, complex, and often contradictory presence in the book. A woman forged in the crucible of 1970s evangelical fervor, she is at once devout, maternal, eccentric, and infuriatingly resolute.

Her past is storied—having walked across America with her then-husband as part of a Christian mission, she embodies both adventure and submission. In the present, she is deeply conservative, relying on scripture and prayer to navigate a world that has shifted dramatically from her formative years.

Her love for her son is never in question; it is fierce and loyal, but also constrained by a theology that casts his sexuality as sinful. Rather than confront this head-on, she often deflects or spiritualizes such conversations, cloaking rejection in a mantle of divine concern.

She is not a villain in the narrative, though. Jenkins portrays her with tenderness and nuance, revealing a woman who survived betrayal, raised children alone, and weathered her own spiritual and emotional storms.

Barbara’s belief system is both her armor and her prison; it gives her strength and identity, but also limits her capacity for transformation. What’s striking is how human she remains throughout—charming, stubborn, hopeful, occasionally maddening, yet always driven by what she believes to be love and righteousness.

These two characters form the emotional core of Mother, Nature. Their road trip through the American landscape becomes a mirror for their emotional topography: beautiful, fraught, familiar, and full of unspoken terrain.

Their conversations, silences, prayers, and laughter illustrate a deep familial love straining under the weight of ideological rigidity and generational dissonance. Jenkins’ brilliance lies in portraying this not as a tragedy, but as a complicated truth—one many readers may recognize in their own relationships.

Themes

The Fractured Intimacy Between Parent and Adult Child

At the heart of Mother, Nature lies a complex and painful intimacy between Jedidiah Jenkins and his mother, defined not by estrangement but by a persistent emotional ache. Their bond is tender yet fraught, built on a lifetime of shared memories, love, and an ever-present ideological rift.

As an adult son who has chosen a life path and identity fundamentally at odds with his mother’s religious convictions, Jenkins inhabits the space between closeness and alienation. They share meals, stories, podcasts, and hotel rooms, and yet there remains an insurmountable distance—his longing for unconditional acceptance and her inability to offer it in the form he needs.

This fractured intimacy is especially raw because it does not manifest as outright rejection; rather, it simmers in avoidance, in prayers that imply change, and in silences that speak volumes. Jenkins portrays their relationship with a kind of bruised reverence: she is a woman of faith, love, and survival, but her affection is channeled through a worldview that sees parts of her son’s identity as wrong.

The emotional power of their story stems from this tension—not that they have stopped loving each other, but that their love cannot reconcile a fundamental disagreement. It’s a portrait of many modern parent-child relationships where generational, political, and spiritual differences do not break the bond entirely but transform it into a more fragile, careful, and sometimes sorrowful connection.

Ideological Polarization Within Families

The road trip narrative becomes a staging ground for America’s wider cultural schisms, dramatized through the conversation, behavior, and inner reflections of Jenkins and his mother. Their respective ideological ecosystems are sharply defined—she listens to conservative talk radio and believes in spiritual warfare; he is gay, progressive, and skeptical of religious literalism.

This divide is not abstract but viscerally experienced in their time together, whether it is choosing which podcast to play, interpreting natural disasters, or confronting theological positions on sexuality. The author never caricatures his mother; instead, he captures the subtler dimensions of ideological difference that exist even in loving families.

There is a kind of ambient sadness in how deeply entrenched both sides are—not out of stubbornness, but because their beliefs are rooted in lived experience and personal truths. The book captures the claustrophobic feeling of being trapped in a vehicle with someone you love but cannot fully speak to.

It is not merely political disagreement; it is a fundamental dissonance in worldview that touches every aspect of their identity, memory, and hope. Jenkins’ writing makes it clear that while ideological division is a societal issue, its most painful consequences are often experienced in private—in conversations that fail, in questions avoided, in the haunting realization that even love has its limitations when worldviews are irreconcilable.

The Role of Memory in Healing and Hurting

Memory functions throughout the narrative as both balm and blade. As Jenkins and his mother retrace the journey she once took across America in the 1970s, memory becomes a shared landscape through which they attempt to reconnect.

Revisiting old towns, reading her journals, and retelling stories provide moments of warmth and mutual understanding. Yet these same memories also illuminate the emotional distance between who they were and who they have become.

For his mother, memory often serves as a stabilizing force, reaffirming her faith and life choices; for Jenkins, it brings forth both nostalgia and grief. He sees the cost of his mother’s decisions, the silencing of her own needs, the way she became shaped by faith and sacrifice.

Their shared past contains points of convergence but also highlights the divergence in values and beliefs that has grown with time. Memory, in this book, is not static—it is activated and shaped by place, emotion, and need.

Jenkins uses memory not to romanticize the past but to hold it accountable, to ask what it means to love someone whose past decisions directly affect your present pain. At times, their mutual recollections seem like attempts to rewrite or rescue their relationship.

But as the trip continues, memory becomes a sobering reminder that some emotional distances are not easily closed, even when the road ahead is a shared one.

The Incomplete Nature of Love Without Acceptance

Love, in Mother, Nature, is everywhere—spoken, enacted, remembered—but always weighed against the unfulfilled promise of full acceptance. Jenkins’ mother clearly loves her son.

She prays over him, cares for him on the road, makes jokes, and shares her life. And yet, for Jenkins, love that does not accept his sexuality fully is incomplete.

This forms one of the most poignant tensions in the book: can love still be called love when it demands erasure or compromise of one’s core identity? Jenkins wrestles with this quietly, introspectively.

He doesn’t demonize his mother but instead illustrates the pain of being seen as broken by someone whose love he otherwise trusts. The reader sees how love can be both steadfast and conditional—offered freely but always within the constraints of belief systems.

What makes this portrayal so powerful is that Jenkins does not force a conclusion. He neither condemns his mother outright nor absolves her entirely.

Instead, he allows the love to stand as it is: real, enduring, but painfully incomplete. The book implicitly questions whether familial bonds can remain strong when one side cannot validate the other’s truth.

It’s a question that echoes across many relationships affected by religion, culture, or generational norms, and Jenkins explores it with honesty and emotional precision.

Nature as a Reflection of Inner States

The physical journey through America’s vast landscapes serves as a mirror to the internal emotional states of both Jenkins and his mother. From the deserts of Texas to the mountains of Colorado and the Pacific coast of Oregon, the natural world is constantly present as backdrop and metaphor.

The land is aged, scarred, breathtaking, and unpredictable—qualities that parallel the state of their relationship. When Jenkins experiences emotional pain, it is often against a backdrop of stark beauty or quiet wilderness, underscoring how the external world can feel both indifferent and strangely resonant with human experience.

Nature does not offer answers, but it often offers clarity. It strips away distractions, forcing the pair to confront each other without the usual domestic buffers.

The road itself, with its twists and detours, mimics the process of trying to reach understanding or even emotional truce. Jenkins often experiences moments of awe in nature that give him temporary peace, but even those moments are complicated by the internal dissonance he carries.

The beauty of the world doesn’t erase the pain of familial misunderstanding—it merely holds it in a different light. Nature, then, is not a healing force in the book, but a contextual one.

It allows for pause, for reflection, and occasionally, for quiet communion between mother and son—even when words fail.