My Time to Stand Summary and Analysis

My Time to Stand is Gypsy-Rose Blanchard’s brutally honest memoir – the woman at the center of one of America’s most disturbing true crime stories. This memoir is not just about a crime—it is about captivity, trauma, awakening, and the search for identity after a lifetime of deception.

Raised under the suffocating control of her mother, Clauddine “Dee Dee” Blanchard, who suffered from Munchausen syndrome by proxy, Gypsy-Rose was forced to live as a sick, disabled child for years. This book serves as both her confession and her declaration of survival, offering a deeply personal lens on the abuse she endured and her eventual bid for freedom.

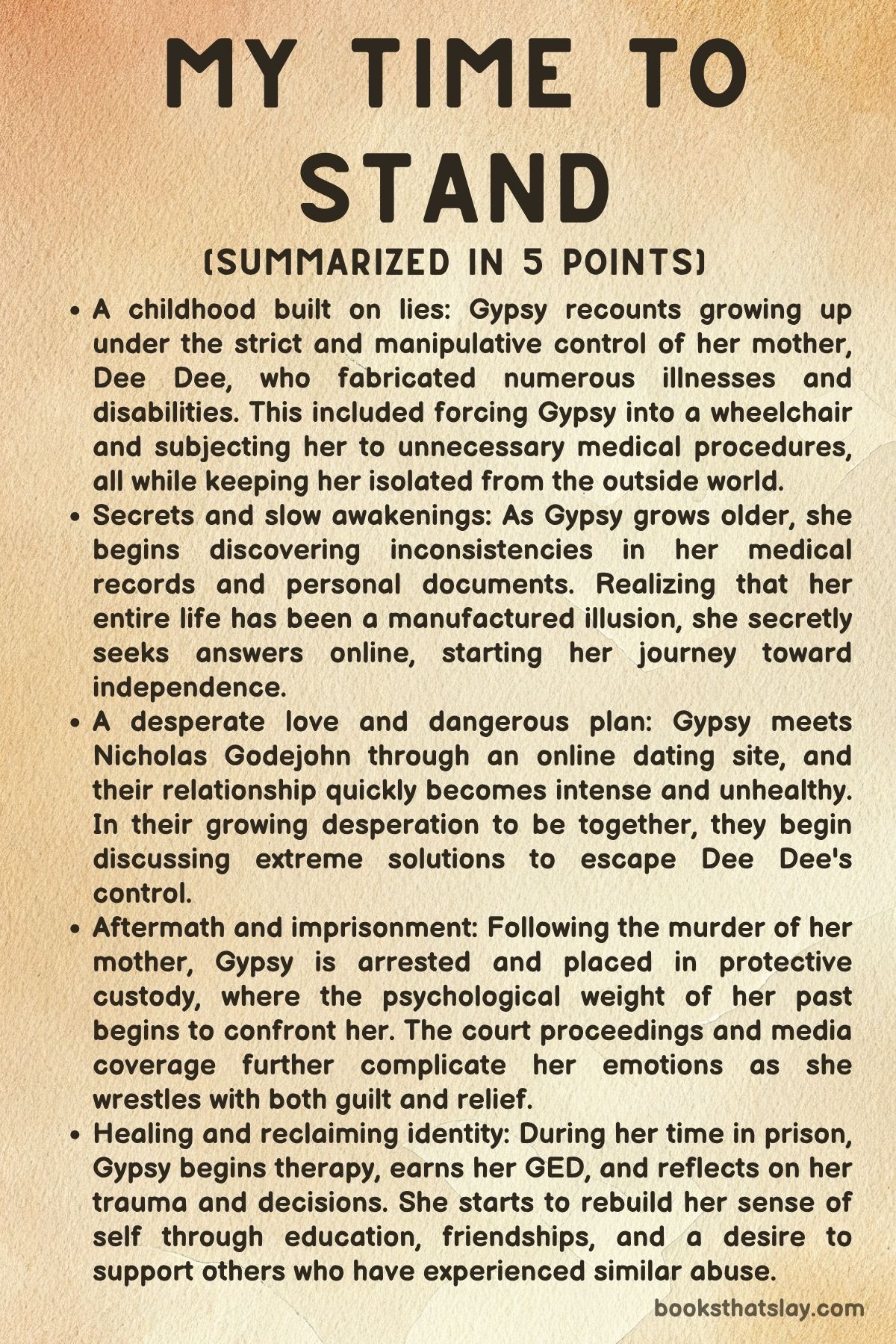

Summary

From the very beginning, My Time to Stand takes readers into the unique and disturbing world Gypsy-Rose grew up in. It was a world shaped by lies, manipulation, and medical abuse.

In the earliest chapters, Gypsy introduces us to the moment she realized she wanted to escape. A botched surgery on her mother’s throat becomes symbolic of the control Dee Dee exerted over every part of Gypsy’s life.

Her reflections are somber and filled with physical and emotional aftershocks, now intensified by prison walls. She delves into her roots, revealing the Cajun-French heritage of her family.

She explains how Dee Dee’s instability, hoarding, and delusions were overlooked or enabled for years. Dee Dee’s behavior is spotlighted as erratic and dangerous.

She isolated Gypsy from her father, her family, and society. She controlled every aspect of Gypsy’s life, from her clothes and food to her identity and body.

Gypsy was portrayed as terminally ill, mentally delayed, and unable to walk. In reality, she was perfectly capable of walking and thinking independently.

She was forced into infantilization—kept in diapers, fed via feeding tubes, and subjected to unnecessary surgeries and medications. Gypsy recounts harrowing experiences of abuse, including being physically restrained and emotionally gaslit.

She describes being subjected to threatening rituals involving voodoo symbols—psychological terror wrapped in faux-mysticism. Despite the severe manipulation, moments of awareness begin to break through.

One turning point comes when she discovers her real birthdate on a Medicaid card. She realizes she’s older than she’d been led to believe.

That sparks a dangerous curiosity, and soon, she secretly accesses the internet. She begins meeting people who show her a life beyond her mother’s control.

Her first escape attempt—an ill-fated plan involving an older man—ends with severe beatings and renewed isolation. But her second brush with the outside world changes everything.

She connects online with Nicholas Godejohn, a man whose own psychological issues and violent tendencies ultimately mesh destructively with Gypsy’s desperation. Their relationship escalates into unhealthy fantasies and intense emotional dependence.

They begin discussing detailed plans to kill Dee Dee. Before this, Gypsy tried to stage encounters between Nick and her mother in hopes of gaining acceptance.

One such attempt happens at a movie theater and fails. As her plans grew darker, Gypsy still hoped for a fairy tale outcome.

She believed she could escape and find love. On June 9, 2015, the murder occurs.

Gypsy waits in the bathroom as Nick stabs Dee Dee in her sleep. She helps clean the crime scene and flees with Nick.

They stay in a motel where the dissonance between her imagined freedom and the brutal reality starts to sink in. Their hideout is surreal—Gypsy tries to cling to a twisted fantasy of romantic liberation.

Internally she begins unraveling. Within days, they are located and arrested.

The media frenzy begins, and Gypsy’s story becomes a national spectacle. From jail, Gypsy starts to process her trauma.

She is placed in solitary confinement, where the irony of being more “free” than ever before hits her hard. In therapy, she begins to understand the psychological abuse she endured.

She learns about trauma bonding and the deep confusion between love and control. She watches Nick’s trial unfold, where their private texts and fantasies are exposed.

Gypsy chooses a plea deal, accepting a 10-year sentence for second-degree murder. It’s a decision both devastating and liberating.

In prison, Gypsy grows. She earns her GED, explores therapy, and starts to form new relationships built on trust.

She reevaluates her feelings for Nick. She realizes their connection was born from trauma, not love.

She reflects on her mother—not with hatred, but with a complex mix of sorrow, anger, and forgiveness. Dee Dee’s voice still lingers in her head, but no longer holds dominion.

Toward the end of the memoir, Gypsy begins writing letters and advocating for victims of invisible abuse. She prepares for life after incarceration.

The final chapters are filled with a sense of cautious hope. She is no longer just a victim or a criminal—she is a woman reclaiming her voice.

She is standing for herself and choosing to live on her own terms. The story concludes with emotional clarity, but not finality.

Gypsy knows her journey isn’t over—it’s just finally her own.

Key People

Gypsy-Rose Blanchard

Gypsy-Rose emerges as a deeply complex and evolving figure. She is initially presented as a helpless, infantilized girl trapped within a meticulously constructed web of lies by her mother.

As the memoir unfolds, she transforms from passive victim to a woman reckoning with the consequences of her desperate bid for freedom. Her voice is reflective and painfully self-aware.

She charts the psychological toll of years of medical abuse, emotional manipulation, and isolation. Initially unsure of her own reality, Gypsy slowly unravels the truth of her physical abilities and identity.

She discovers her real age, the fact that she can walk, and that the dozens of illnesses she was told she had were fabrications. Her awakening is catalyzed by the internet, where she begins to find fragments of normalcy, love, and the tools for escape.

However, her journey is not linear. Even after the murder of Dee Dee, Gypsy is not immediately free.

She trades one prison for another. Through therapy and prison education, she gradually learns to articulate her trauma.

She begins to recognize unhealthy patterns, particularly in her relationship with Nick. Eventually, she reclaims her autonomy.

In the Epilogue, Gypsy reasserts herself not as a symbol of victimhood but as someone who has survived extraordinary psychological torment. She chooses to grow, heal, and advocate for others.

Clauddine “Dee Dee” Blanchard

Dee Dee is a profoundly disturbing figure, simultaneously pitiable and monstrous. She is not merely an abusive mother but the orchestrator of an elaborate deception.

She consumes her daughter’s body and mind through years of manipulation. Suffering from Munchausen syndrome by proxy, Dee Dee subjects Gypsy to unnecessary surgeries and medications.

She uses feeding tubes, performance scripts, and staged illnesses to paint herself as a saintly caregiver. Her manipulation extends to lies about Gypsy’s age, education, and abilities.

What makes Dee Dee’s abuse particularly insidious is her use of affection and guilt as weapons. She infantilizes Gypsy, keeps her in diapers, and frames herself as the only person capable of caring for her.

Dee Dee is also haunted by her own trauma, including childhood sexual abuse. This trauma may have distorted her perception of protection and control.

Yet she remains unrepentant and tyrannical. She uses physical abuse, voodoo superstitions, and psychological terror to maintain dominance.

Even after her death, Dee Dee’s presence lingers. Her voice echoes in Gypsy’s mind as a cruel reminder of how entrenched her control was.

Nicholas Godejohn

Nick is a deeply unsettling yet pivotal character in Gypsy’s story. He exists in a murky space between romantic savior and dangerous enabler.

Introduced as an online boyfriend, Nick initially offers the escape and validation Gypsy craves. But his role quickly turns darker.

He introduces BDSM dynamics, violent sexual fantasies, and murder plots under the guise of love. Nick suffers from multiple mental health challenges.

He is emotionally immature, obsessive, and socially isolated. His interpretation of love becomes intertwined with control and dominance.

Though Gypsy initially clings to him as a rescuer, she later realizes he represents another form of imprisonment. His trial reveals disturbing fantasies and behaviors.

These revelations challenge any simplistic view of him as just a misguided lover. In prison, Gypsy understands that what she felt with Nick was not love—it was desperation and manipulation.

Rod Blanchard

Rod, Gypsy’s biological father, plays a marginal but important role in the memoir. He is manipulated and pushed away by Dee Dee early on.

Rod appears as a symbol of the “normal” life Gypsy could have had. He is portrayed as kind but distant.

Rod is often misled by Dee Dee’s fabricated stories of Gypsy’s declining health. Despite the lies, his love for Gypsy seems genuine.

He sends gifts and tries to remain present, though his involvement is consistently sabotaged. Later, after the truth emerges, Rod supports Gypsy emotionally and publicly.

He expresses remorse for not seeing the truth sooner. His character serves as a counterpoint to Dee Dee’s domination.

Rod represents a different kind of parenting—one that is flawed by absence but grounded in genuine affection rather than control.

Kristy Blanchard

Kristy, Rod’s wife and Gypsy’s stepmother, is a minor but noteworthy presence in the memoir. She enters Gypsy’s life through Rod and offers a sense of stability.

Kristy shows genuine concern for Gypsy, especially after Dee Dee’s death. Though she appears briefly, her presence is significant.

She reinforces the idea that not all maternal figures are manipulative or abusive. Kristy helps support Gypsy’s transition from trauma toward healing.

She becomes part of the foundation for Gypsy’s reimagined future. Her care stands in contrast to Dee Dee’s domination and deceit.

Themes

Abuse and Psychological Control

My Time to Stand is a harrowing account of sustained psychological, emotional, and medical abuse. Gypsy-Rose Blanchard details how her mother, Dee Dee, manipulated her into believing she was gravely ill for most of her life.

This manipulation extended to fabricating symptoms, enforcing unnecessary surgeries and medications, and misrepresenting Gypsy’s age and capabilities. The abuse was systemic and totalizing, covering every aspect of Gypsy’s life—from basic bodily autonomy to her understanding of time and identity.

Dee Dee’s actions weren’t merely physical acts of control but psychological imprisonments that conditioned Gypsy to fear the outside world and to depend solely on her mother. Even when Gypsy discovered fragments of truth—her real age, her ability to walk—she was so entrenched in fear and dependence that escape felt impossible.

The abuse was normalized and framed as care, which made it more insidious. This memoir not only exposes the disturbing reach of Munchausen syndrome by proxy but also challenges societal assumptions about visible versus invisible suffering.

The reader is compelled to confront the reality that abuse can wear a smile, be sanctioned by institutions, and remain hidden in plain sight for years.

Isolation and Infantilization

Gypsy’s narrative is marked by extreme isolation and enforced infantilization. Dee Dee systematically stripped away Gypsy’s access to the outside world, including formal education, friendships, and even unsupervised conversations.

She was homeschooled under the pretense of being too fragile for school and was denied a normal adolescence. She was kept in diapers well past puberty, placed in a wheelchair despite being able to walk, and fed through a feeding tube long after she could eat independently.

Dee Dee’s desire to control Gypsy’s body extended into her emotional and cognitive development. Gypsy was taught to view herself as helpless and broken.

Infantilization served a dual purpose: it reinforced Gypsy’s dependence on her mother and maximized public sympathy. That sympathy translated into financial aid, charity support, and societal validation for Dee Dee.

The childlike persona Gypsy was forced to perform became both a prison and a shield. It protected Dee Dee’s lies while eroding Gypsy’s autonomy.

Even when Gypsy began seeking independence, the lingering psychological effects of infantilization made her choices naïve, impulsive, and anchored in a distorted sense of identity. This theme underscores how robbing a person of adulthood is not just about controlling their actions but about sabotaging their future.

Search for Identity

The memoir is also a deeply personal account of Gypsy’s struggle to understand and reclaim her identity. For years, she lived under false pretenses—her age falsified, her health conditions invented, her memories confused by contradictory realities.

Her name, birthdate, and medical records were all manipulated to the point that Gypsy did not know who she truly was. As she began discovering her medical records and real birth certificate, the world she thought she knew started to collapse.

But discovering the truth was only the beginning. Gypsy’s path to self-definition is riddled with confusion, guilt, and fear.

She initially tried to reclaim herself through online personas and relationships, especially with Nicholas Godejohn. These attempts were built on desperation and fantasy rather than genuine self-awareness.

Her identity had been so thoroughly shaped by abuse that even freedom felt foreign. Only through therapy, education, and time did Gypsy begin to construct a new sense of self, separate from Dee Dee’s narrative.

This evolution is gradual and painful, but crucial. The memoir becomes more than just a recounting of trauma—it is a declaration of selfhood by someone whose very personhood had been denied for most of her life.

Freedom and Responsibility

Freedom in My Time to Stand is portrayed as a paradox. Gypsy physically escapes her mother’s control only through an act of extreme violence, yet she quickly finds herself behind bars—trading one prison for another.

The book explores the distinction between external freedom and internal liberation. While Gypsy is finally outside Dee Dee’s grasp, she is not emotionally or psychologically free.

In fact, prison offers her a strange kind of safety and space for introspection that she never had before. Through therapy and time, Gypsy begins to understand her role in the crime, not as a monster, but as a deeply wounded individual acting out of desperation.

She takes responsibility for her actions without denying the years of abuse that led to them. Her choice to take a plea deal, reflect on her trauma, and use her story to advocate for others reflects a mature understanding of freedom.

Freedom, in this context, is not about avoiding consequences but about reclaiming one’s narrative. It is about shaping the future with intention.

Gypsy’s liberation is not romanticized. It is earned through pain, effort, and self-reflection.

Love, Manipulation, and Codependency

Gypsy’s relationship with Nicholas Godejohn is central to the narrative. It serves as a case study in how trauma can distort one’s understanding of love.

Raised without appropriate models of affection, Gypsy equated control with care and fantasy with connection. Her relationship with Nick was forged in secrecy and desperation, bound together by their shared delusions and mutual neediness.

Initially, Gypsy viewed Nick as a savior—someone who could rescue her from Dee Dee. However, the relationship quickly devolved into unhealthy codependency.

It was marked by manipulative dynamics, disturbing fantasies, and escalating violence. It is only in the latter chapters that Gypsy begins to realize that what she experienced was not love but another form of control.

The insight does not come easily. It requires detaching from the comforting illusion that someone once chose her and staying honest about the harm that relationship caused.

Her decision to break ties with Nick, even while in prison, is one of the most emotionally significant moments in the memoir. It marks her first step toward understanding that real love cannot exist without freedom, boundaries, and truth.

In learning to separate affection from possession, Gypsy redefines what it means to care for herself and others.

Healing and Advocacy

The final chapters and the epilogue focus on Gypsy’s ongoing healing and her desire to help others. Rather than positioning herself solely as a victim or a criminal, Gypsy embraces the complexity of her experiences.

She participates in therapy, earns her GED, develops friendships in prison, and begins using her voice for advocacy. Her healing is not portrayed as linear or complete.

It is a process filled with setbacks, haunted memories, and difficult self-examinations. However, it is also marked by growth, clarity, and empowerment.

Gypsy’s goal becomes not just to survive but to ensure that other victims of covert abuse, especially psychological manipulation and Munchausen by proxy, are seen and supported. She uses her story to highlight the failures of medical institutions, law enforcement, and social services.

These systems allowed her abuse to go unnoticed. By speaking out, writing her memoir, and considering a future in advocacy, Gypsy reclaims her agency.

She no longer sees herself through the eyes of the public or her abusers. She sees herself as someone with a unique voice capable of making a difference.

Healing, in this book, is not about forgetting. It is about choosing what comes next.