Never Whistle at Night Summary, Analysis and Themes

Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology is not just a horror collection—it’s a cultural reckoning.

Curated with piercing insight and creative intensity, this anthology brings 26 chilling short stories from Indigenous authors across North America, blending traditional horror with colonial trauma, folklore, grief, and resistance. Each tale is unique, but all are connected by an undercurrent of Indigenous survival, transformation, and ancestral presence. Whether it’s shape-shifting spirits, haunted artifacts, or the deep psychological horrors born from history, the book’s voices crackle with life and mourning. These aren’t just ghost stories—they’re warnings, memories, and reclamations wrapped in shadows.

Summary

Never Whistle at Night unfolds as a mosaic of horror stories from Indigenous perspectives, where each tale reflects a specific cultural lens, a historical wound, or a re-imagined folklore brought vividly—and often terrifyingly—to life.

The book opens with “Kushtuka”, where a young woman faces a doppelgänger spirit drawn from Tlingit lore, echoing generational trauma and manipulation. In “White Hills,” horror hides behind suburban wealth as a pregnant influencer becomes a victim of racist eugenics disguised as maternal care. The ancestral and supernatural clash again in “Navajos Don’t Wear Elk Teeth,” when two cousins find a bewitched elk tooth in a pawn shop that thrusts them into a spiritual crisis.

“Wingless” gives us a symbolic transformation: a grieving girl literally grows feathers and wings, a reflection of her emotional isolation and bodily autonomy. In “Quantum,” the boundaries of science and spirit blur as an Indigenous physicist taps into a multiverse of ancestral memory, accidentally tearing open portals to unresolved cultural trauma.

Stories like “Hunger” take a grotesque turn—here, a young woman consumes her abusive family, in a metaphor of spiritual starvation and reclamation of power. “Tick Talk” critiques digital vanity through the lens of a cursed TikTok trend, where social media summons something truly demonic.

In “The Ones Who Killed Us,” ghosts from a massacre rise to demand justice, revealing how colonial violence festers in the land and memory. “Snakes Are Born in the Dark” explores cursed bloodlines through serpentine horror, and “Before I Go” provides a meditative confrontation with death as a man journeys across spiritual waters to find peace.

The second half deepens the anthology’s psychological and symbolic horror. In “Night in the Chrysalis,” a girl in a residential school undergoes a grotesque metamorphosis to escape colonial imprisonment. “Behind Colin’s Eyes” features a cursed mask that erodes identity, while “Heart-Shaped Clock” traps a grieving mother in loops of time, memory, and mourning.

“Scariest. Story. Ever.” offers dark humor, poking fun at storytelling traditions, while “Human Eaters” depicts cannibalistic monsters born from land desecration. “The Longest Street in the World” becomes a surreal metaphor for generational grief, and “Dead Owls” haunts a woman with ancestral vengeance in feathered form.

In “The Prepper,” isolation becomes literal horror, as a man’s survivalist fears materialize into a supernatural siege. “Uncle Robert Rides the Lightning” brings mythic power into the modern day, with a girl’s storm-wielding uncle standing as protector and warning. “Sundays” traps a boy in a looping domestic nightmare where every week turns darker.

The final stories focus on spiritual reckoning and psychological breakdown. In “Eulogy for a Brother, Resurrected,” a funeral turns into a resurrection gone wrong. “Night Moves” shows a girl haunted by the ghosts of missing Indigenous women as she walks the streets of memory. “Capgras” spirals into paranoia as a man believes his family is being replaced.

“The Scientist’s Horror Story” warns against mishandling traditional knowledge, while “Collections” awakens ancestral spirits stored in forgotten objects. The anthology ends with “Limbs,” where a man’s severed body parts return, infused with the spirit of the land and the weight of stolen lives.

Altogether, Never Whistle at Night is a visceral journey through the haunted landscapes of Indigenous experience—where horror is more than fiction; it’s cultural truth wrapped in shadow and resistance.

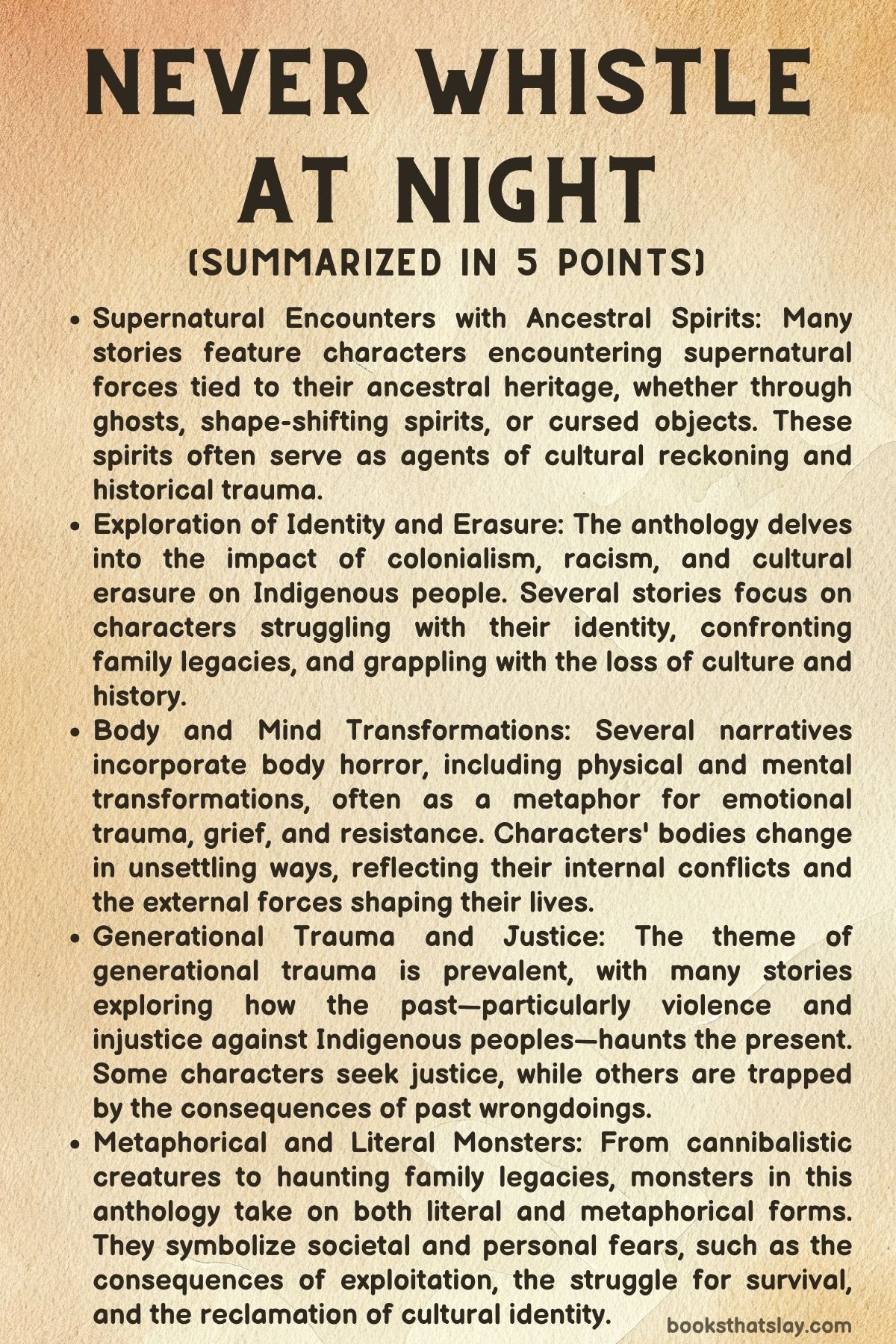

Analysis and Themes

Colonial Trauma and Ancestral Reckoning

The theme of colonial trauma is woven through many of the stories, often in ways that reflect not just historical oppression but its haunting, lingering impact on the present. The horrors described in these stories are not just supernatural for the sake of thrills; they are manifestations of the violence and erasure that Indigenous communities have faced for centuries.

In stories such as The Ones Who Killed Us and Night Moves, ghosts and spirits act as powerful symbols of the unresolved wounds caused by colonization, genocide, and the displacement of native peoples. These spirits do not merely haunt—they demand acknowledgment, reminding both their perpetrators and descendants of the historical wrongs that cannot be buried.

The supernatural forces in these tales often serve as an avenue for ancestral voices to rise up, compelling the living to confront their complicity in maintaining oppressive systems and to seek reparation or justice.

The Unraveling of Identity and the Fragility of Memory

Another recurring theme is the fragility of identity, often explored through psychological horror. Stories like Capgras and Behind Colin’s Eyes delve into the disintegration of personal and cultural identity.

In Capgras, the protagonist becomes consumed by paranoia, believing his loved ones are being replaced by impostors. This delusion reflects a deeper fear of losing one’s sense of self and the anxiety of cultural erasure. Similarly, Behind Colin’s Eyes involves a man who is granted the ability to see through another person’s eyes, but this power leads to an erosion of his own identity as he begins to lose touch with his own sense of self.

This theme extends beyond personal delusion to encompass collective memory, as characters wrestle with inherited trauma, loss of cultural landmarks, and the destabilizing force of colonization that redefines their pasts.

The Interplay of Grief, Transformation, and Rebirth

Many of the stories examine the relationship between grief and transformation. In Wingless and Night in the Chrysalis, the protagonists’ emotional suffering physically transforms them—one into a bird-like creature and the other into a literal insect.

These metamorphoses are symbolic of the characters’ struggles with loss and isolation.

Grief here is not merely an emotional burden but a force that reshapes the body and mind, mirroring the disintegration of personal and cultural connections. Transformation, however, is not always a negative force; it can also serve as a form of escape or rebirth.

In Eulogy for a Brother, Resurrected, grief leads to a chilling resurrection, where the brother’s body refuses to stay dead, symbolizing the cyclical nature of death and memory, and the unresolved business between the living and the dead. In these narratives, transformation is deeply tied to the characters’ attempts to reclaim or reconstruct identity in the face of overwhelming loss.

Spiritual Responsibility and the Dangers of Cultural Appropriation

A cautionary tale emerges in The Scientist’s Horror Story, where a scientist’s reckless use of sacred Indigenous knowledge results in a catastrophic supernatural event.

This story critiques the historical and ongoing exploitation of Indigenous culture, particularly the appropriation of spiritual practices and traditional knowledge by non-Indigenous individuals who fail to understand their significance.

The scientist’s actions are a direct metaphor for the larger issues of cultural theft and disrespect, where Indigenous traditions are commodified or misused for personal gain.

This theme underscores the importance of respecting Indigenous knowledge and the sacredness of ancestral stories, warning against the consequences of treating such knowledge as something that can be detached from its cultural and spiritual context.

Body Horror and the Physical Manifestation of Colonial Guilt

The theme of body horror in the anthology is used as a visceral tool to explore the psychological and emotional toll of colonialism.

Stories like Limbs and Human Eaters employ the grotesque to reflect on the trauma caused by colonial violence and the desecration of Indigenous bodies. In Limbs, the protagonist loses his limbs in a car accident, only for them to return in ghostly form, embodying a form of spiritual vengeance tied to the mistreatment of Indigenous remains.

This body horror connects the destruction of physical bodies with the desecration of Indigenous cultures and lands, offering a poignant metaphor for how colonialism continues to extract life and vitality from native peoples.

In Human Eaters, the monstrous spirits that pursue the protagonists are manifestations of a broken relationship with the land, representing a literal and figurative consumption of Indigenous bodies and resources, as well as the unrelenting hunger for what has been lost.

Resistance, Survival, and the Power of Ancestors

Despite the overwhelming darkness in many of these stories, survival and resistance emerge as central themes.

In Uncle Robert Rides the Lightning, the protagonist’s uncle uses his supernatural control over storms as a form of defense against those who threaten his community. This story suggests that survival can be an act of resistance—a way of reclaiming power and protecting one’s heritage from external forces.

Similarly, many stories in the anthology reflect the resilience of Indigenous peoples, whose survival is not just a matter of physical endurance but also the strength to hold onto identity, memory, and culture in the face of erasure.

Ancestors, as seen in Collections and Dead Owls, serve as guiding figures whose presence and power remain unyielding even after death. These stories emphasize that Indigenous survival is not just about living through trauma but about honoring those who came before and continuing to fight for a future that acknowledges and respects the past.