North is the Night Summary, Characters and Themes

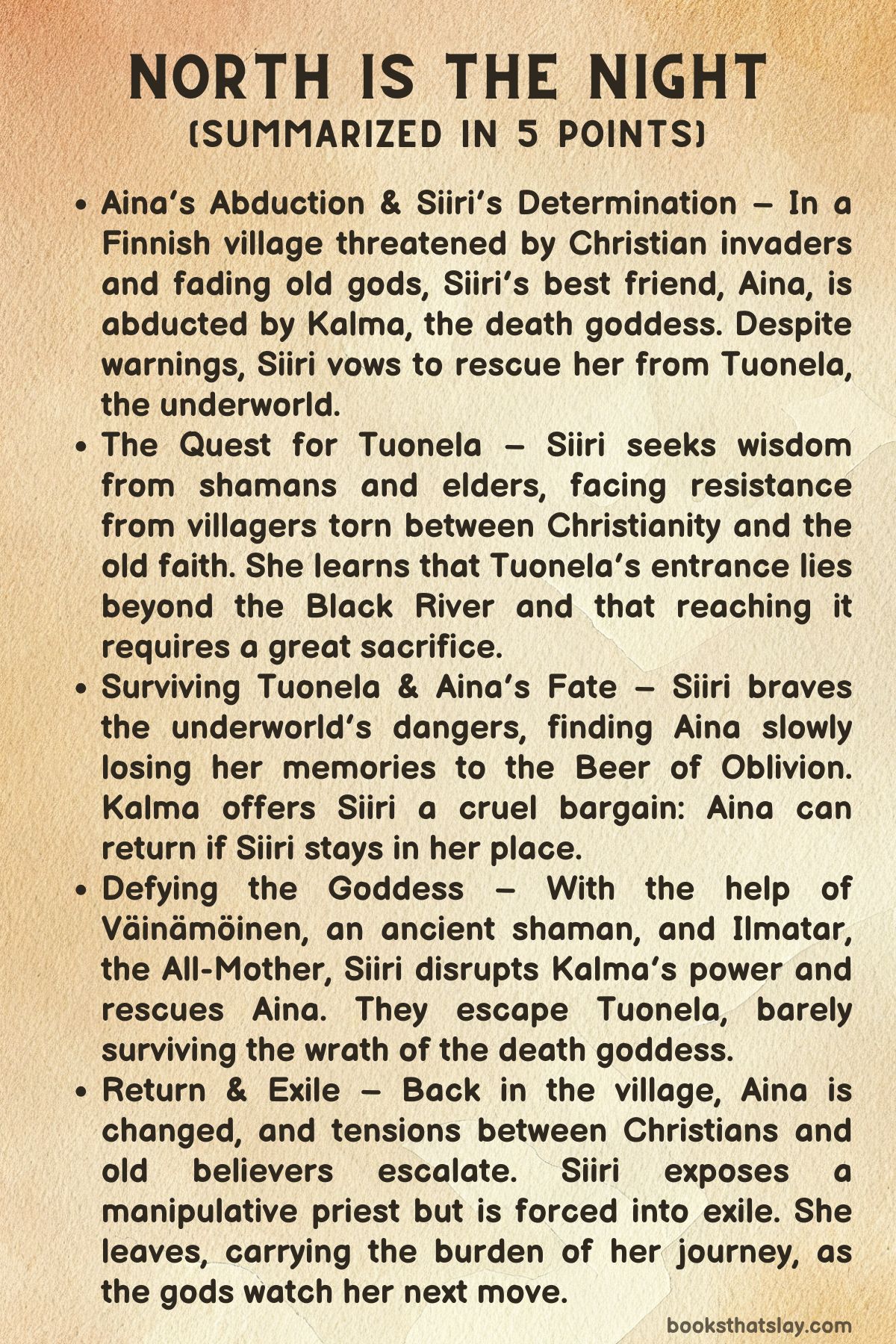

North Is the Night by Emily Rath is a lush and emotionally intense reimagining of Finnish mythology, centered on themes of love, defiance, cultural identity, and the sacred power of women. The story follows Siiri and Aina, two young women whose bond defies mortality, patriarchy, and spiritual conquest.

When Aina is taken by the death goddess Kalma, Siiri’s determination to rescue her transcends the physical and propels her into a divine struggle. What begins as a personal mission quickly transforms into a mythic campaign to revive the forgotten gods, protect ancestral legacies, and reshape the balance between life and death.

Summary

Siiri lives in a remote Finnish village where she spends her days helping her father with the essential fishing and salting tasks needed to survive the brutal winter. Her heart belongs to her closest friend Aina, a girl full of dreams about love and motherhood.

Siiri, however, wants nothing more than to preserve their deep bond, secretly harboring feelings that extend beyond friendship. Their lives are upended when a terrifying, spectral woman clothed in black—a figure possibly representing the goddess of death, Kalma—appears by the lake and takes Aina, vanishing into the shadows with a spectral wolf.

Siiri’s attempts to protect Aina fail, and she is overwhelmed with guilt, believing she was the intended victim. In her despair, she calls out to the All-Mother, pleading to be taken too.

Instead, she is awakened by a mysterious woman with glowing eyes who urges her to rise and “save us. ” Taken home by her family, Siiri recounts what happened.

Her grandmother, Mummi, believes Aina has been dragged to Tuonela, the land of the dead. While others advise Siiri to stay quiet and accept Aina’s fate, she resolves to rescue her, even if it means descending into the underworld.

Siiri visits Aina’s mother, Milja, who gives her blessing, affirming that if anyone could defy death, it would be Siiri. But the priest in the village blames Aina’s disappearance on sin, fueling Siiri’s anger and deepening her commitment to the old gods.

She begins to see herself not only as Aina’s savior but as a spiritual warrior tasked with reawakening divine powers nearly lost to time. Her grandmother’s old stories fuel her purpose, and Siiri embarks northward to seek Väinämöinen, the legendary shaman.

Simultaneously, Aina awakens in a mysterious, enchanted space where abundance and rot exist side by side. A supernatural raven named Jaako is her only companion.

She slowly realizes she is in Tuonela, where time warps, food turns to mold, and bruises appear without cause. The isolation gnaws at her, and the eerie setting makes her question her sanity, but her will to survive persists.

Siiri’s journey brings her into a sacred grove where she meets the goddess Tellervo, who has been abandoned by worshipers and defiled by invaders. This encounter marks Siiri as a bridge between gods and mortals.

She continues north and eventually reaches Väinämöinen, who is fragmented—his soul divided into henki, luonto, and itse. One part, the itse, resides in a bear named Kal.

Siiri assists in reuniting the shaman’s soul, learning soul magic along the way and offering her own essence as a vessel to travel into Tuonela.

Meanwhile, Aina is taken deeper into Tuonela by Tuoni, the god of death. The palace, once shrouded in darkness, begins to awaken with warmth and light under Aina’s presence.

Tuoni urges her to take the throne and dethrone Tuonetar, the cruel Witch Queen. Despite doubts, Aina agrees—not out of ambition, but to protect others.

Tuonetar resists, but her daughter Kalma betrays her, allowing Aina to disarm the queen and take her wand. Aina’s show of mercy—insisting Tuonetar not be killed but dine with her daughters—reveals her strength lies in compassion, not vengeance.

Aina demands Tuoni release the kidnapped mortal girls and never abduct the living again. She threatens him with a blade to both their throats, binding the pact with a kiss that marks the beginning of a complicated romance between the god of death and the newly crowned queen of Tuonela.

Aina remains behind, queen of the underworld, as the rescued girls are sent back to the living world under magical protection.

Siiri learns the full truth from Väinämöinen and commits to using her own essence to find Aina. As she crosses into Tuonela, a climactic confrontation ensues.

Tuonetar launches a final attack, but Aina, now fully Ainatar, rallies the dead to her side. Tuoni sacrifices himself to protect Aina and Siiri from a wave of destruction.

He emerges in his true, fiery form, shielding them with a wall of flame, and then vanishes. This act of love and sacrifice redeems him in Aina’s eyes.

Siiri and Aina return to the living world, where Väinämöinen’s hut is under siege by Lumi and her wolves. Siiri helps defend him, and in a painful act of mercy, grants him the death he was long denied.

With this act, she inherits his magic and mantle, becoming the new Väinämöinen. Lumi is defeated, symbolizing the victory of transformation over stagnation.

Back in the village, Siiri reunites with her family and reveals that Aina lives—and that she is carrying Kalev, the son of Tuoni and Aina. The lost girls return home.

Aina acknowledges her complicated heart: though Tuoni has a place in it, it is Siiri who holds her soul. Together, they raise Kalev, a child who bridges the realms of life and death.

As the seasons pass, Siiri and Aina prepare for the future. With Siiri as the shaman and Aina as queen of Tuonela, they are no longer just girls defying the gods.

They are leaders, symbols of cultural endurance and spiritual rebirth. The story concludes with a promise of revolution: to reclaim their land, protect their people, and restore the sacred harmony between humans and the divine.

Characters

Siiri

Siiri is the emotional and mythic heart of North Is the Night, beginning as a loyal daughter in a harsh Finnish village and evolving into a spiritual warrior of immense depth and symbolic resonance. Initially depicted as diligent and compassionate, Siiri embodies a fierce commitment to family and friendship, particularly through her devotion to Aina.

Her identity is deeply rooted in tradition—she participates in fishing, salting, and reveres the lore passed down by her grandmother, Mummi. When Aina is abducted, Siiri’s anguish transforms into purpose.

She defies her family’s passive fatalism and the rising tide of Christianity that labels Aina’s abduction as divine punishment, asserting instead her allegiance to the old gods and a belief in love’s ability to defy death.

Siiri’s journey from grief-stricken friend to chosen champion of the old faith is both literal and symbolic. She navigates a treacherous spiritual wilderness, not just of land but of belief, challenging the dominance of new religious paradigms.

Her defiance becomes an act of cultural resistance, and her interactions with Väinämöinen mark her initiation into a sacred legacy. Eventually, she volunteers to use her soul’s essence—her itse—as a means to reach Tuonela, exhibiting not just bravery, but a sacrificial love rooted in mythic heroism.

Siiri’s ultimate transformation into the new Väinämöinen after granting the old shaman a merciful death signifies her acceptance of leadership, sacrifice, and the burdens of rebirth. She bridges ancient myth with modern resistance, embodying faith, grief, and an unyielding love that transcends death and time.

Aina

Aina’s character is a mesmerizing portrayal of inner strength, endurance, and eventual ascendance to divine sovereignty. At first, Aina represents warmth, joy, and hope—she is a source of light in Siiri’s life, dreaming of motherhood and stability.

Her abrupt abduction catapults her into an otherworldly prison, where she experiences a surreal entrapment marked by illusion, decay, and isolation. Confined to a mystical space that mimics comfort before descending into rot, Aina undergoes a slow, harrowing awakening to her circumstances, paralleled by a growing metaphysical awareness.

Her only consistent companion is Jaako, a supernatural raven whose guidance tethers her sanity and intuition to the ancient myths of her homeland.

Aina’s metamorphosis culminates in her elevation as Ainatar, Queen of Tuonela, where she does not triumph through violence but through love, compassion, and mercy. Her showdown with Tuonetar—the dethroned, tyrannical Witch Queen—showcases her moral clarity and spiritual resolve.

She demands mercy for Tuoni’s daughters and asserts her power not by conquest but by healing a broken kingdom. Her romantic entanglement with Tuoni, while fraught with danger and desire, is ultimately a nuanced dance of power and intimacy.

Aina maintains agency, choosing how and when to love, and redefining death itself through acts of mercy. By the novel’s end, she is not just a queen of the dead, but a living symbol of renewal, maternal strength, and emotional sovereignty.

Her bond with Siiri—profoundly platonic yet soul-deep—grounds her, and her child Kalev becomes the living bridge between realms.

Tuoni

Tuoni, the god of death, emerges as a complex, enigmatic, and ultimately redemptive figure in North Is the Night. Initially portrayed as a terrifying and forceful deity who abducts Aina, Tuoni exudes an aura of menace, mystery, and suppressed vulnerability.

His early actions—possessive, dominating, and rooted in old-world power—echo the archetypal dark god figure, yet his narrative arc dismantles this trope through the slow revelation of grief, longing, and deep-seated loneliness. Tuoni’s palace, once decayed under Tuonetar’s reign, blossoms into golden grandeur upon Aina’s arrival, a metaphor for his own rekindled hope and emerging emotional resonance.

His relationship with Aina becomes the axis of his transformation. He begins to relinquish control, respond to love, and even accept Aina’s demand for personal sovereignty.

His decision to restore his palace, revive the dead, and allow Aina to lead marks a seismic shift in Tuoni’s identity—from sovereign tyrant to devoted consort. His final act of sacrifice, shielding Aina and Siiri from Tuonela’s destructive tide with his own divine flame, completes his evolution.

Tuoni is no longer just death; he becomes its guardian, one tempered by love, vulnerability, and the desire for connection. His letter to Aina about their son Kalev reveals tenderness and yearning, showcasing his growth from captor to companion and father.

In embodying both destruction and devotion, Tuoni becomes a mythic force of duality—death as both ending and transformation.

Väinämöinen

Väinämöinen is the soul of Finland’s mythic tradition brought into flesh, depicted in North Is the Night as a shaman fractured by time, loss, and disconnection from his divine essence. When Siiri seeks him out, he is a broken man, physically diminished and spiritually scattered.

The division of his soul—into henki, luonto, and itse—renders him incomplete, embodying the consequences of divine neglect and cultural erasure. Väinämöinen is not just a mentor figure but a symbol of fading ancestral wisdom.

He passes his knowledge to Siiri, acknowledging that the future belongs to the youth, the bold, and the faithful.

His death, at Siiri’s hand and his own request, is one of the novel’s most poignant moments. It is not just a death, but a transference—a sacred rite of passage in which the old world entrusts the new with its memory and power.

Through this act, Väinämöinen is immortalized, not in body but through legacy. His blessing transforms Siiri into the new shamanic force of the land, a living heir to ancient truths.

Väinämöinen’s character reminds readers that heroism is not only in action, but in letting go—allowing others to carry the torch forward into unknown futures.

Tuonetar

Tuonetar, the Witch Queen, stands as the embodiment of cruelty, decay, and oppressive immortality. Her reign over Tuonela is steeped in tyranny and darkness, built on manipulation, torture, and spiritual stasis.

She is the antagonist not only of Aina and Tuoni but of transformation itself. Her power clings to the status quo of suffering, refusing to yield even as the kingdom around her shifts toward renewal.

Yet even in her fall, Tuonetar retains a grim dignity. Her taunts and resistance to Aina’s mercy reflect a tragic inability to evolve, a tyrant consumed by her own legend.

Kalma’s betrayal reveals that even her own daughters find her rule untenable. Her exile, enforced by magical chains once used on Tuoni, is a fitting reversal.

Aina’s choice to offer her a seat at the dinner table—despite her crimes—demonstrates the new regime’s contrast: one rooted in compassion over cruelty. Tuonetar thus becomes not just a defeated villain, but a cautionary monument to power misused and love forsaken.

Kalma

Kalma, the feared death-daughter of Tuonetar, is a character shrouded in ambiguity, dread, and ultimately, quiet defiance. First introduced as a monstrous woman cloaked in shadow, she is the figure who abducts Aina and strikes terror into Siiri.

However, as the story progresses, Kalma’s true complexity surfaces. Despite her initial violence, she aids Tuoni and Aina from within the shadows, revealing a soul torn between inherited cruelty and buried compassion.

Her decisive act—turning against her mother and aiding in Tuonetar’s defeat—shifts the narrative lens. Kalma becomes a tragic figure, forced into monstrousness by lineage, yet brave enough to reject her origins.

Her visit to see Kalev near the novel’s end signals a yearning for connection, absolution, and perhaps a future beyond fear. Kalma represents the buried wounds of generational trauma and the possibility of redemption through quiet, sacrificial resistance.

Jaako

Jaako, the raven spirit and Aina’s supernatural companion, functions as both a guide and enigma throughout her captivity. Speaking in riddles, disappearing without warning, and offering cryptic insights, Jaako embodies the old myths of animal familiars—part mentor, part messenger.

His true allegiance is unclear for much of the story, and his presence evokes unease as much as comfort. Yet, as Aina gains clarity, so does Jaako’s purpose: he is a tether to the mythic realm, a reminder of the sacred stories embedded in the natural world.

In many ways, Jaako reflects Aina’s inner journey. He challenges her perceptions, forces her to trust instinct over appearances, and leads her toward empowerment.

He is the guardian of memory and a living fragment of the vanished divine. His final appearances are solemn but affirming, as he watches over Kalev and Aina’s transformation.

Jaako represents the wisdom of the wild—the sacred voice that endures even in silence.

Themes

Cultural Survival and Ancestral Faith

The story of North Is the Night reverberates with the fierce urgency of preserving cultural identity in the face of spiritual colonization. Siiri’s refusal to adopt the teachings of the Swedish priest or apologize for her beliefs is not just an act of personal defiance but a declaration of loyalty to a spiritual legacy being erased by foreign religion.

Her community’s increasing deference to Christian doctrine, and her father’s violent insistence on obedience, symbolize the internal fractures that colonial influence breeds within a culture. Siiri’s journey is rooted in the belief that the gods of her ancestors still live, even if abandoned.

Through her bond with Mummi and the myths she was raised on, Siiri fights not merely for Aina’s life but for the soul of her people. Her trek north is a pilgrimage of faith, one that reignites divine presence and demands reverence where there was resignation.

This act of spiritual resistance becomes an argument for cultural survival, asserting that faith must not bend to conquest but evolve through continuity and belief. The revival of Väinämöinen and the reawakening of forgotten gods demonstrate that ancestral power is not dead but dormant, needing champions like Siiri to stir it awake.

The narrative insists that memory and myth are essential threads of identity, and in fighting for them, Siiri becomes the living embodiment of a heritage worth preserving.

Love as Devotion, Not Possession

At the heart of Siiri’s actions lies a love that transcends romance and enters the domain of sacred loyalty. Her bond with Aina is not defined by overt confessions or mutual desire but by unshakeable commitment.

Siiri’s decision to journey into the land of the dead is not framed as heroic martyrdom, but as something she considers necessary, even inevitable—because to live while Aina is lost would be a kind of spiritual death. This kind of love, rooted in constancy rather than possession, informs many of the book’s most powerful moments.

When Siiri confronts divine forces or negotiates with the dead, she does so not to claim Aina, but to protect her. The distinction is vital.

Aina, meanwhile, forms a complex emotional bond with Tuoni, the god of death. Their connection, volatile and intimate, suggests that love can also arise in shadowed places, provided it is tempered by mutual respect.

Aina’s insistence on loving Tuoni on her own terms contrasts with Tuonetar’s dominion, where power meant subjugation. Love in North Is the Night is constantly examined through the lens of agency: who chooses, who follows, and who sacrifices.

It is not the domain of men alone, nor is it clean or uncomplicated. It is love that reclaims the throne from tyranny, that calls back the dead, and that reshapes the very laws of the afterlife.

In both its platonic and romantic forms, love becomes the force that steadies the living and redeems the divine.

Female Empowerment and Spiritual Authority

Siiri and Aina’s arcs illustrate a rare model of female leadership that refuses to imitate masculine authority. Rather than drawing power through violence or control, their strength lies in choice, compassion, and conviction.

Siiri becomes the new Väinämöinen not through conquest but through sacrificial empathy—choosing to take on the burden of a dying shaman and accepting the cost of becoming more than herself. Her magic is rooted in memory, soul, and connection to the natural world.

Aina, by contrast, earns her throne not through bloodshed but by restoring what was lost, transforming Tuonela from a place of despair into one of order and mercy. Her confrontation with Tuonetar is not just a political coup but a spiritual exorcism of cruel power, one that affirms a different kind of queenship.

Aina’s refusal to exile Tuonetar completely, insisting instead on shared meals, marks a radical departure from the cycle of vengeance that once ruled the underworld. Through these choices, the narrative positions feminine power not as secondary or reactive, but as regenerative and sovereign.

The transformation of both women—Siiri into shaman, Aina into queen—represents the arrival of a new mythic era led not by warriors or patriarchs but by women who carry the memory of their people and the will to protect them. Their roles are not symbolic or ceremonial; they are deeply practical, sacred, and necessary for the world to heal.

The Moral Reclamation of the Divine

Tuoni and Kalma, once terrifying figures associated with death and decay, are rendered with moral complexity that challenges preconceived notions of good and evil. Tuoni is introduced as a god of death who abducts the living, yet his gradual evolution under Aina’s influence reframes him as a figure capable of grief, change, and even love.

His ultimate act of sacrifice, protecting Aina and Siiri from annihilation, strips away his identity as captor and recasts him as guardian. Kalma’s redemption, too, underscores this theme.

Originally a figure of dread, she reveals herself as an ally working against Tuonetar’s tyranny, driven by a hidden loyalty to her father and the well-being of Tuonela. These revelations disrupt the binary of divine benevolence and cruelty.

Even Tuonetar, as monstrous as she becomes, is shown to be driven by the trauma of abandonment and the desperation to retain relevance. The gods are not immutable forces but participants in the same cycles of pain, love, and transformation as mortals.

This moral reframing allows the story to argue that divinity is not about perfection or dominance but about the willingness to change and to protect. In showing how the gods respond to mortal love, defiance, and belief, North Is the Night asserts that redemption is not the exclusive province of humans.

It is available even to the most fearsome of gods, provided they are willing to be seen, challenged, and loved.

Rebirth Through Memory and Sacrifice

The concept of rebirth—both literal and spiritual—courses through the narrative as the ultimate expression of transformation. Whether it is Väinämöinen’s painful return through the restoration of his three soul parts, or Siiri’s transcendence into his role through death and rebirth, the story treats memory and sacrifice as the engines of becoming.

The world does not change through violence alone, but through the willingness to remember and to give up part of oneself for something greater. Siiri’s sacrifice of her own itse in service of another echoes throughout her arc, culminating in her assumption of a shaman’s legacy not as inheritance, but as earned right.

Aina’s ascent to queenship is likewise framed as a process of remembering who she was—daughter, friend, beloved—and integrating that into her new identity. Rebirth here is not a clean slate but a continuity of self across trauma, myth, and love.

Even Tuoni, once chained and humiliated, is reborn as a partner and protector. The birth of Kalev, a child born of death and life, becomes the most literal and hopeful embodiment of this theme.

He is not just a child but a symbol of unity between worlds, and his name, chosen by Siiri, roots him in the legacy of a people still fighting to be remembered. North Is the Night ends not with closure but with continuity, showing that the future must grow out of memory and be watered by sacrifice, if it is to mean anything at all.