Northanger Abbey Summary, Characters and Themes

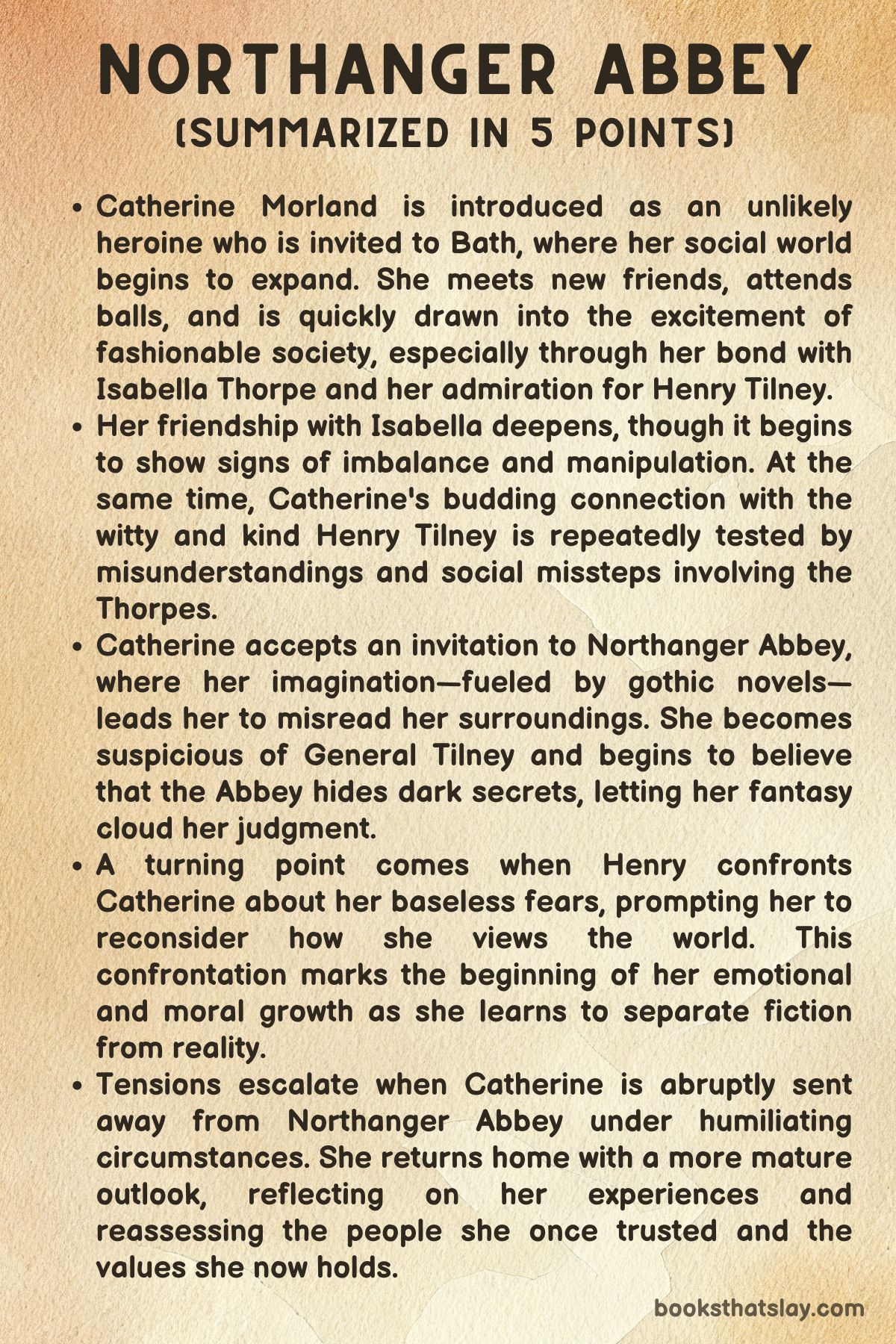

Northanger Abbey is a satirical coming-of-age novel by Jane Austen. The book follows the story of Catherine Morland, a young woman with a passion for gothic novels, who experiences her first brush with society, romance, and self-awareness during a stay in Bath and later at the mysterious-sounding Northanger Abbey.

Through Catherine’s journey, Austen critiques the sensationalism of popular gothic fiction while subtly examining class, manners, and personal integrity.

Summary

Catherine Morland, the unlikely heroine of Northanger Abbey, begins life in a thoroughly unremarkable fashion. Raised in a large, comfortable family in Fullerton, she shows little promise of becoming a traditional protagonist.

She is neither especially beautiful nor particularly talented, but she is kind-hearted, affectionate, and imaginative. As she grows older, her appearance and social interest improve, and she develops a strong affinity for reading novels, especially the Gothic romances that spark her expectations of grand adventure and mystery.

Her first opportunity for excitement arrives when she is invited to accompany the Allens, family friends, to Bath. Mrs.

Allen, though shallow and fashion-obsessed, proves a suitable chaperone in society. Upon arrival, Catherine is both dazzled and overwhelmed by the city’s energy and formality.

Initially without acquaintances, she has little success at the Upper Rooms but soon attracts attention at the Lower Rooms, where she meets the witty and charming Henry Tilney. Their playful conversation impresses her and sparks the beginnings of an emotional attachment.

Catherine is later reunited with her brother James and introduced to the Thorpe family. She quickly forms an intense friendship with Isabella Thorpe, whose theatricality and enthusiasm for novels mirror Catherine’s own romantic inclinations.

However, Isabella’s affection masks a calculating nature. Her brother, John Thorpe, aggressively pursues Catherine with self-centered arrogance, misinterpreting her politeness as romantic interest.

Catherine is too naive and passive to correct him, often swept into awkward situations.

Meanwhile, Catherine continues to think fondly of Henry Tilney. She meets his sister, Eleanor, and finds her to be composed, kind, and sincere—a refreshing contrast to Isabella’s performative friendship.

The Tilney siblings’ refined manners and gentle disposition appeal to Catherine’s growing sense of discernment. Henry’s intelligence and humor deepen her admiration, and she is delighted when the Tilneys invite her to visit their family estate, Northanger Abbey.

The journey to Northanger Abbey marks a turning point in Catherine’s inner life. The grandeur and antiquity of the estate stimulate her imagination, and she begins to entertain morbid fantasies inspired by the Gothic novels she adores.

She becomes suspicious of General Tilney, Henry and Eleanor’s father, interpreting his stern demeanor and mysterious behaviors as signs of a dark secret. Convinced he is hiding something sinister about his deceased wife, Catherine explores the house in search of evidence.

Her assumptions culminate in a moment of humiliation when Henry gently confronts her, clarifying that his mother died of natural causes and that her flights of fancy are inappropriate and unfounded.

This confrontation is pivotal in Catherine’s development. It forces her to reckon with the difference between fiction and reality, marking the beginning of her emotional maturation.

Her deepening bond with Henry is now based on mutual understanding rather than imagined heroics. She continues to enjoy her stay, forming a stronger friendship with Eleanor and feeling increasingly at ease in the Abbey’s refined environment.

However, the pleasant mood is abruptly shattered when General Tilney suddenly sends Catherine away without explanation. Distressed and bewildered, she travels back to Fullerton alone, humiliated and heartbroken.

Her family receives her with sympathy, though her mother, practical and unsentimental, cannot fully understand her emotional turmoil. Catherine struggles in silence, mourning both her ruined prospects and the inexplicable rejection by the Tilneys.

The mystery is soon resolved by Henry’s arrival at Fullerton. He explains that John Thorpe, once eager to inflate Catherine’s wealth to advance his sister’s ambitions, had later spitefully disparaged her after being rejected himself.

The General, misled by Thorpe’s shifting stories, initially believed Catherine to be an heiress but changed his attitude once he perceived her as penniless. Henry, however, refuses to be governed by his father’s prejudices and proposes to Catherine without his approval.

This act cements Henry’s status as a morally upright and independent character. His decision validates Catherine’s affection and signals a more mature, equal relationship.

Eventually, the General’s disapproval is softened when Eleanor Tilney marries a wealthy nobleman, improving the family’s social standing. Realizing that the Morlands are not impoverished and that Catherine’s character is sound, the General relents and allows the marriage to proceed.

Catherine and Henry’s union is presented as a happy one, though Austen characteristically couches this conclusion in irony. The narrator questions whether the story champions rebellion or submission, inviting readers to ponder the balance between romantic ideals and practical morality.

The novel ends with a marriage that affirms Catherine’s journey from gullible girl to discerning young woman, her development shaped not by dramatic adventure, but by quiet lessons in humility, love, and truth.

The annotated edition adds layers of meaning by contextualizing the social norms, domestic details, and architectural references that shape the story. It offers explanations of period customs, such as servant management and drawing room rituals, and explores the use of architecture and decor to signal class status.

The commentary also draws attention to Austen’s subversion of Gothic tropes, emphasizing her preference for realism and ethical depth over sensational drama. Through Catherine’s missteps and eventual growth, Northanger Abbey reveals how imagination, when tempered by reason, can lead to genuine insight and emotional fulfillment.

Characters

Catherine Morland

Catherine Morland, the protagonist of Northanger Abbey, is introduced with satirical irony as a young woman strikingly unfit for the traditional role of a Gothic heroine. Raised in a large, unpretentious family in Fullerton, Catherine is initially awkward, plain, and uninterested in conventional feminine pursuits.

However, her endearing good nature, imagination, and resilience set her apart. As she matures into adolescence, she gains social awareness and a romantic sensibility influenced heavily by her love for novels, especially Gothic fiction.

This passion for melodrama leads her to superimpose fictional tropes onto real-life situations, particularly during her stay at Northanger Abbey, where she misreads the environment through a lens of mystery and suspense. Catherine’s journey is one of emotional and intellectual development; her missteps—most notably, her suspicion that General Tilney may have imprisoned or murdered his wife—stem from an overactive imagination, not malice.

Through experience and gentle correction, particularly from Henry Tilney, she grows into a more discerning and self-aware woman. By the novel’s conclusion, Catherine emerges as someone who has retained her warmth and sincerity but tempered them with maturity, showing that true heroism lies not in grand gestures but in integrity, empathy, and personal growth.

Henry Tilney

Henry Tilney serves as both a romantic interest and a moral compass in Northanger Abbey. Introduced as a witty, intelligent, and perceptive clergyman, he distinguishes himself immediately from the more pompous and egotistical male characters, such as John Thorpe.

His playful teasing and irony reflect both his charm and his ability to see through social pretensions. Henry’s conversations with Catherine often reveal his appreciation for literature and language, as well as his subtly feminist perspective—particularly when he surprises Catherine with his knowledge of muslin and women’s fashion.

Unlike the typical Gothic hero, Henry is grounded and realistic, treating others with kindness while also insisting on personal integrity. His criticism of Catherine’s Gothic-inspired suspicions at Northanger Abbey is firm but respectful, serving as a pivotal moment in her maturation.

Later, his defiance of his authoritarian father to marry Catherine affirms his moral courage and emotional authenticity. His love is not rooted in idealized fantasy but in genuine admiration for Catherine’s character, and his actions underscore Austen’s vision of a hero who values intellect, empathy, and principled independence over bravado or social ambition.

General Tilney

General Tilney, the patriarch of the Tilney family, represents the imposing authority and rigid social stratification of Georgian England. He is a man obsessed with wealth, status, and appearances, and he treats his home and his family as extensions of his public image.

At Northanger Abbey, he guides Catherine through elaborate tours of the estate, clearly seeking to impress her and subtly influence her toward marriage with Henry—believing her to be an heiress. His later abrupt and cruel dismissal of her upon learning of her modest financial background reveals the transactional nature of his regard for others.

Despite Catherine’s exemplary behavior, the General values social connections more than personal merit. He is also emotionally manipulative, exerting control over his daughter Eleanor and expecting unquestioning obedience from his sons.

General Tilney’s character serves as Austen’s critique of patriarchal and materialist values, showcasing the dangers of ambition untempered by affection or humility. In the end, his reversal—prompted not by remorse, but by Eleanor’s advantageous marriage—further underscores his superficiality and the hollowness of his values.

Isabella Thorpe

Isabella Thorpe is a vivid portrait of social opportunism and performative femininity in Northanger Abbey. Initially charming and vivacious, Isabella quickly befriends Catherine with seemingly heartfelt enthusiasm, bonding over shared interests in fashion, flirtation, and novels.

However, her true character emerges gradually through her manipulative and self-serving actions. Her flirtations with multiple men, even while engaged to Catherine’s brother James, reflect her fickleness and insincerity.

Isabella is adept at using emotional language to manipulate others, often claiming passionate loyalty while subtly positioning herself for better prospects. When she realizes that James lacks significant wealth, her interest in him diminishes, and she sets her sights on Captain Tilney, Henry’s brother, in hopes of elevating her status.

Her transparent ambition and betrayal of both James and Catherine exemplify Austen’s satire of social climbing and false sentiment. Isabella’s downfall is not dramatic but socially damning—exposed and alienated, she loses the respect of those whose favor she tried to court, becoming a cautionary figure for the perils of artifice and vanity.

John Thorpe

John Thorpe embodies the worst traits of masculine arrogance and self-delusion. Loud, boastful, and self-centered, he consistently overestimates his own appeal and importance.

His conversations are riddled with exaggerations and contradictions—he praises his horse, carriage, and wealth with inflated claims that fail to hold up under scrutiny. John presumes Catherine’s affection without ever truly engaging with her feelings or interests, treating her more as a possession to be acquired than as a person.

His selfish behavior repeatedly inconveniences and embarrasses her, such as when he withholds crucial information or causes her to miss planned meetings with the Tilneys. More seriously, his reckless lies about Catherine’s financial standing—motivated by spite and wounded pride—nearly destroy her prospects with the Tilney family.

Through John, Austen critiques male entitlement, the dangers of unchecked ego, and the social system that tolerates such figures due to their gender and perceived status.

Eleanor Tilney

Eleanor Tilney is the embodiment of quiet strength and grace in Northanger Abbey. As the daughter of General Tilney and sister to Henry, she navigates a constrained and authoritarian household with composed dignity.

Eleanor is reserved but warm, displaying genuine kindness and sensitivity toward Catherine. Their friendship contrasts starkly with Catherine’s superficial bond with Isabella, offering a model of sincere and respectful female companionship.

Eleanor’s own life is shaped by restraint and patience; she submits to her father’s rigid expectations while quietly maintaining her moral autonomy. Her eventual marriage to a titled man not only elevates her social position but also indirectly facilitates Catherine’s union with Henry, as it softens General Tilney’s opposition.

Eleanor’s character represents the silent endurance and moral clarity Austen admired in women—capable of profound influence not through defiance, but through constancy and inner resolve.

Mrs. Allen

Mrs. Allen provides comic relief and subtle social commentary throughout Northanger Abbey.

Vapid, fashion-obsessed, and perpetually distracted by concerns over muslin and gowns, she is nonetheless well-meaning and kindly. As Catherine’s chaperone in Bath, Mrs.

Allen is both ineffectual and harmless—unable to guide Catherine in any meaningful social or moral way, yet always eager for a good shopping trip or a walk in the Pump Room. Her lack of depth is not malicious but simply a product of her limited worldview.

Austen uses Mrs. Allen to poke fun at the superficialities of polite society, especially the feminine preoccupation with appearances, while also showing that even such characters can play essential roles in a young woman’s social development.

Mr. and Mrs. Morland

Catherine’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Morland, are portrayed as sensible, affectionate, and grounded. They represent the sturdy middle-class values of practicality, moderation, and moral integrity.

Mr. Morland is an honest clergyman with a preference for plain sense over display, while Mrs.

Morland is a caring and reasonable mother who treats Catherine with a blend of affection and pragmatic advice. Their reaction to Catherine’s social opportunities and romantic entanglements is notably understated—they offer neither melodramatic warnings nor excessive encouragement.

When Catherine returns home in distress, Mrs. Morland’s rational attempts to comfort her highlight the emotional gap between youthful idealism and parental realism.

Their steadfast presence provides a solid moral center against which Catherine’s adventures and misadventures unfold, underscoring the value of sincerity and simplicity in a world often dominated by show and pretension.

Themes

Identity and Self-Awareness

Catherine Morland’s journey in Northanger Abbey is fundamentally one of self-discovery, shaped by her transition from naive romanticism to grounded self-awareness. Initially presented as an unconventional heroine—neither beautiful nor accomplished—Catherine’s sense of identity is heavily influenced by the novels she consumes.

These stories feed her expectations of drama, mystery, and moral grandeur, which she tries to map onto her own life. Her first experiences in Bath show her eagerness to be noticed and her belief that every social interaction might blossom into a significant romantic or moral episode.

This tendency becomes more pronounced at Northanger Abbey, where she lets Gothic conventions shape her perception of her surroundings and the people in them, especially General Tilney. However, as her fantasies collapse under the weight of reality, she confronts the discomfort of having misjudged not only others but also herself.

Henry Tilney’s calm correction and her own shame catalyze a shift from performative imagination to introspective clarity. Catherine begins to trust her observations rather than her projections, recognizing that self-worth is not validated by matching fictional archetypes.

By the novel’s conclusion, her maturation allows her to engage with the world on more truthful terms. Her marriage to Henry is not just a romantic resolution but a symbol of her fuller understanding of herself—not as a Gothic heroine, but as a young woman who has learned to reconcile imagination with reality and desire with principle.

Satire of Sentimentality and Gothic Excess

The novel critiques the sentimental and Gothic literature that dominated the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Through Catherine’s overactive imagination, fueled by the novels of Ann Radcliffe and her peers, Austen exposes the absurdities and dangers of applying fictional logic to real-life situations.

Catherine’s suspicions about General Tilney—imagining him as a domestic tyrant who has imprisoned or murdered his wife—highlight the disconnect between melodramatic expectations and ordinary moral complexities. Her tendency to interpret the Abbey’s grandeur and isolation through a Gothic lens becomes an opportunity for Austen to mock not just the genre’s excesses but also the kind of superficial moral drama it promotes.

Rather than being punished for real vices, Gothic villains are often judged for aesthetic qualities—dark hallways, thunderclaps, or ancestral secrets—whereas Austen insists on assessing behavior through consistent, observable conduct. Even Catherine’s confrontation with the mundane truth of Mrs.

Tilney’s death underlines Austen’s point: real human suffering and moral failures do not require supernatural trappings. Moreover, the novel ridicules the emotional overstatements common in sentimental fiction, seen in the exaggerated proclamations of Isabella Thorpe or John Thorpe’s inflated view of himself.

Through irony and narrative commentary, Austen distinguishes between genuine feeling and theatrical excess, encouraging the reader to value moral clarity, emotional restraint, and realistic portrayals of character over literary melodrama.

Social Ambition and Class Anxiety

Social mobility and class consciousness are deeply embedded in the motives and actions of nearly every major character. The Thorpes represent a form of social climbing marked by opportunism and deception.

John Thorpe’s constant exaggeration of Catherine’s fortune—and later, his vengeful retraction—shows how economic status is used as leverage in personal and familial advancement. Similarly, Isabella’s shifting affections from James Morland to a more lucrative match reveal the transactional nature of romantic courtship in a society obsessed with wealth.

General Tilney, ostensibly a man of propriety, is driven by this same fixation. His interest in Catherine only persists while he believes she is an heiress; once this illusion is dispelled, he does not hesitate to eject her from Northanger Abbey with cold indifference.

Austen satirizes such behavior as shallow and dangerous, revealing how appearances and misrepresentations can cause real emotional harm. In contrast, Henry Tilney and Eleanor Tilney demonstrate a more grounded understanding of class and character.

Henry’s defiance of his father’s materialistic views marks his moral and emotional independence, while Eleanor’s eventual rise in status through marriage ironically enables the reconciliation between Catherine and the Tilney family. The tension between genuine virtue and social pretense runs throughout the novel, emphasizing that status is an unreliable measure of worth and that affection and compatibility should supersede class-based concerns.

Growth Through Disillusionment

Catherine’s arc is defined by a series of painful awakenings that gradually strip her of naive beliefs and sentimental illusions. Her introduction to Bath society initially feeds her idealism—she expects romantic attention, thrilling social engagements, and dramatic personal developments.

Yet her experiences continually challenge these expectations. She discovers that polite society can be empty and performative, as evidenced by Mrs.

Allen’s triviality and the discomfort of being overlooked at dances. Her friendship with Isabella Thorpe, at first intense and affirming, begins to unravel as she notices inconsistencies, selfishness, and shallow loyalties.

The supposed romance with John Thorpe—wholly invented on his part—serves as another moment of disenchantment, exposing how assumptions and self-deceit can distort relationships. The most significant blow to her imagination comes at Northanger Abbey itself, where her fanciful suspicions about the Tilney family give way to the mundane and painful reality of social rejection.

These disappointments do not harden Catherine but rather refine her understanding of others and herself. Instead of withdrawing into cynicism, she develops a more nuanced sense of trust and judgment.

Her final acceptance of Henry’s love, and his of hers, is grounded in mutual respect and tempered feeling, not theatrical passion. Austen’s treatment of disillusionment as a necessary and constructive process reinforces the idea that wisdom and emotional integrity are earned through missteps and reflection, not bestowed through romantic inspiration.

Parental Authority and Autonomy

The novel presents a nuanced view of parental influence, contrasting supportive guidance with authoritarian control. Catherine’s parents embody a quiet, rational form of parenthood.

They neither coddle nor oppress her, allowing her to experience life in Bath without undue interference. Their practicality—especially Mrs.

Morland’s level-headed advice—serves as a backdrop against which the more dominating figures, like General Tilney, appear tyrannical. General Tilney’s conduct represents a misuse of parental power; his manipulative encouragement of Catherine’s relationship with Henry based on wealth, followed by his cruel expulsion of her upon discovering her modest background, reveals his overbearing desire to control his children’s futures.

His sudden reversal after Eleanor’s fortuitous marriage reveals the self-interest at the core of his supposed authority. In contrast, Henry’s decision to defy his father reflects a maturation into ethical adulthood, where familial respect does not preclude independent moral action.

Austen also explores the emotional impact of such dynamics. Eleanor’s submissiveness to her father is depicted with subtle pathos, suggesting how long-term exposure to such domination limits emotional freedom.

Ultimately, the novel endorses a model of autonomy tempered by respect and compassion. Catherine’s development into someone capable of navigating these power structures—and Henry’s willingness to stand beside her—positions them as figures who uphold individual agency against the weight of patriarchal expectation.

This contrast enriches Austen’s broader commentary on generational responsibility and emotional maturity.