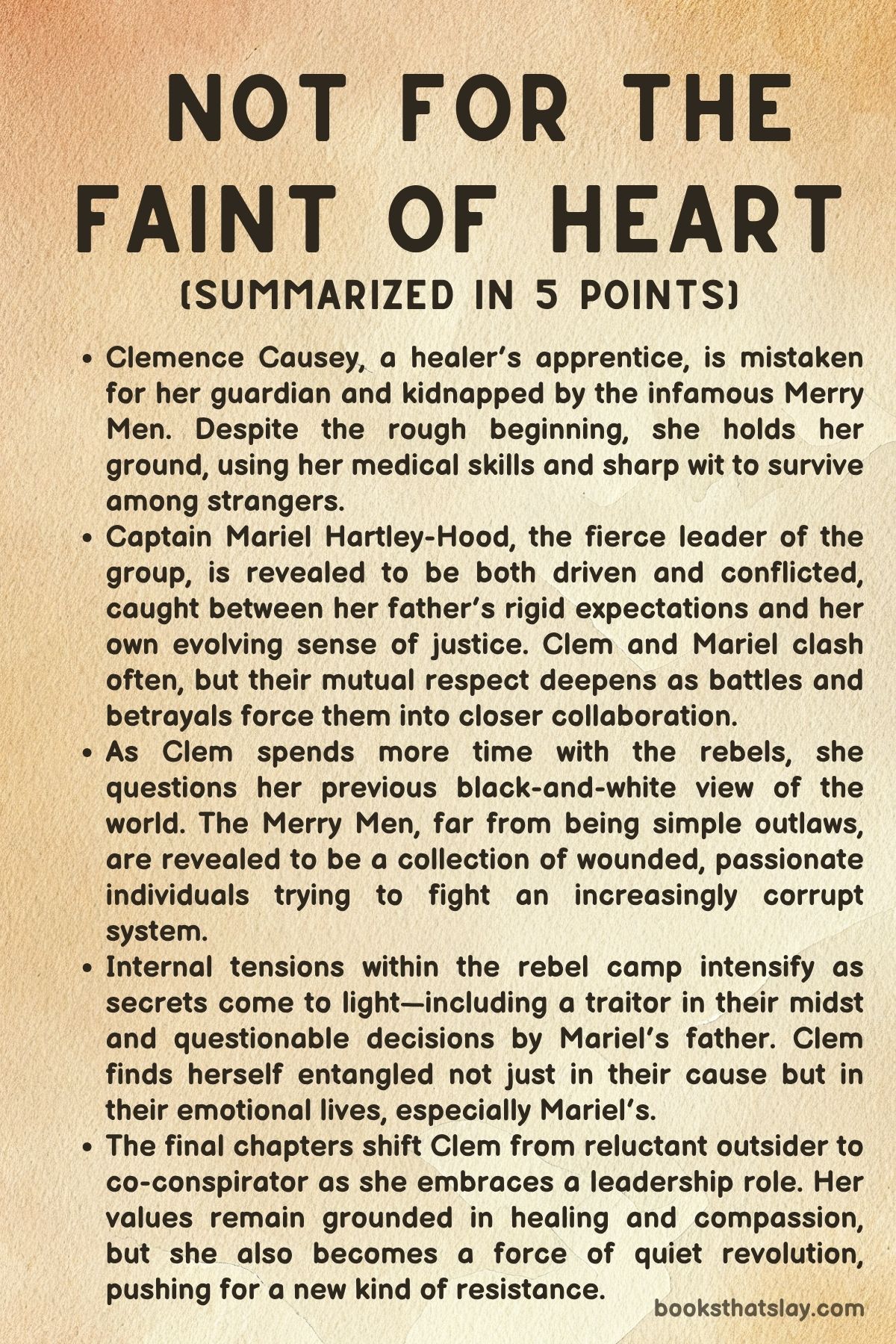

Not for the Faint of Heart Summary, Characters and Themes

Not for the Faint of Heart by Lex Croucher is a vibrant, subversive fantasy that reimagines the Robin Hood mythos through a queer, feminist lens. At its heart, the story follows Clemence “Clem” Causey, a fiercely independent healer whose quiet life is upended when she’s abducted by a militarized version of the Merry Men.

As she’s thrust into the heart of a brewing rebellion, Clem navigates fraught alliances, moral dilemmas, and unexpected friendships. With sharp humor, emotional depth, and richly drawn characters, the novel interrogates heroism, legacy, and the nature of resistance, all while capturing the warmth of found family amid rising danger.

Summary

Clemence “Clem” Causey begins her day with whimsical calm, crafting a tiny hat for a fox. This serene scene is interrupted by the arrival of the Merry Men, who arrest her guardian, Old Rosie, under vague accusations of treason.

Clem, in a moment of protective bravery, offers herself in Rosie’s place. Her offer is accepted, and she is quickly rendered unconscious and taken by the Merry Men.

Mariel, the young captain of this resistance group, makes the decision to take Clem rather than Rosie, hoping the substitution still meets strategic goals while giving her a chance to demonstrate her initiative to her father and commander, Jack Hartley.

Upon waking, Clem is confused and angry. The Merry Men, though not the merry-hearted folk legends suggest, are shown to be a militarized and often callous organization.

Despite being tied up and sedated, Clem begins forming tentative impressions of her captors. She meets Kit, the kind medic; Josey, the cheery but dangerous lieutenant; Baxter, a gentle giant; and Morgan, a sharp, rebellious youth.

Mariel, who leads them, is intense, wary, and emotionally reserved—traits formed by years under her father’s demanding expectations.

Clem’s interactions reveal her sharp wit, bravery, and deep compassion. She tries to present herself as useful to the group by offering her healing skills, but Jack Hartley dismisses her.

Mariel remains suspicious, unconvinced by Clem’s attempt to lie in order to shield Rosie. Clem is disillusioned as she sees the Merry Men not as heroes, but as a grim, bureaucratic militant force.

Things take a drastic turn when the Sheriff’s forces ambush the group. Morgan is badly injured by an arrow, and Clem risks her safety to provide medical aid despite still being a prisoner.

Meanwhile, Mariel engages in a brutal duel with the odious noble Frederic de Rainault and is wounded. Clem finds her and, despite everything, saves her life.

This act complicates their already tense relationship, exposing layers of duty, vulnerability, and mutual misunderstanding.

Although Clem attempts to escape, she is recaptured and returned to camp. Her ability to tend to the wounded earns her a grudging respect.

Mariel, while still emotionally guarded, begins to recognize Clem’s value. Through Clem’s kindness and banter, the walls around the group’s hardened members start to soften.

Simultaneously, Mariel’s backstory is expanded: she is Robin Hood’s daughter, raised in the shadow of a legendary figure and caught between loyalty to her father and her emerging convictions. Her internal struggle deepens as she questions the direction of their cause.

When intelligence reveals that a key prisoner is held at Hanham Hall, Mariel orchestrates a bold rescue. The team splits, using a bard disguise as a distraction while the others infiltrate the buttery.

Mariel’s discomfort with the playful ruse adds humor to the operation. Tensions rise when Morgan, though ordered to stay behind, joins the mission and acts on old trauma by smashing an heirloom belonging to Lord Hanham.

This impulsive act nearly dooms the mission, but they narrowly escape to a hidden rebel base called Underwood.

Underwood offers rare joy—songs, feasting, and laughter. However, Mariel is furious with Morgan and temporarily expels them.

A heartfelt confession reveals Morgan’s need to be remembered by the place that hurt them. Clem and Mariel also share flirtatious, emotionally loaded moments, particularly during an arm-wrestling match and while caring for a drunken Morgan.

These scenes showcase Clem’s ability to challenge Mariel’s stoicism and offer warmth where Mariel has long felt only pressure.

The group’s resolve strengthens after they return to Hanham to liberate more prisoners. Success bolsters morale and deepens their commitment to justice.

Clem’s compassion and Mariel’s evolving leadership bring the group closer together, with even skeptical members beginning to trust Clem. However, tragedy soon strikes.

Baxter Scarlet, the beloved gentle giant, dies during a later mission. His funeral becomes a moment of shared grief and vulnerability.

Clem and Mariel, though still emotionally distant, share silent solidarity. Meanwhile, Clem is once again captured, and her skills as a healer are manipulated for strategic gain.

Mariel’s disillusionment with her father Jack peaks when she learns that Clem has been taken and her estranged mother, Regan, is being used as bait.

Mariel’s friends rally around her, and together they launch a rescue. A fierce battle follows.

Clem, fighting to save others, is gravely wounded by an arrow. Mariel, simultaneously trying to save her mother, learns that Jack exiled Regan years ago for challenging his rigid leadership.

This revelation shakes Mariel’s faith in her father and the structure he built. Though Regan survives, her coldness—particularly her lack of gratitude toward Clem—underscores the cost of idealism unmoored from care.

Clem, barely alive, is saved by Mariel. The act becomes a turning point in both their arcs.

Frederic de Rainault, long portrayed as a sneering noble, unexpectedly shows kindness toward Clem, complicating earlier impressions. As the battle ends, Jack Hartley, now wounded and exposed, offers leadership to Mariel.

She refuses to accept it as inheritance and demands a democratic vote instead.

Mariel’s campaign for leadership is grounded in humility, experience, and responsibility. She is ultimately elected to lead the Merry Men.

Clem remains by her side, their connection deepened by hardship, mutual respect, and emerging love. Together, they envision a future built not on tradition or legend, but on shared values and community.

The story closes with a sense of earned hope. Clem and Mariel, alongside a reformed rebel force, carry forward the legacy of resistance.

They are scarred but stronger, united not by bloodlines or myth, but by the belief that heroism is found in care, courage, and the willingness to change.

Characters

Clemence “Clem” Causey

Clem emerges as a vibrant, complex protagonist whose personality blends humor, empathy, resilience, and a profound moral compass. Initially depicted in Not for the Faint of Heart as a humble healer with whimsical habits—such as making hats for foxes—Clem’s life is quickly upended by her forcible abduction by the Merry Men.

However, even in captivity, she retains her wit and resourcefulness. Her decision to offer herself in Rosie’s place reflects a self-sacrificial spirit, which becomes a recurring element in her character.

Clem’s compassion is underscored during moments of crisis: she risks her own safety to treat Morgan’s wounds during an ambush and later chooses to save Mariel’s life despite their antagonistic history. These actions demonstrate not only medical skill but a defiant kind of kindness that transcends political lines.

Her gradual transformation from a reluctant hostage to an indispensable rebel medic shows how she grows into her power without losing her sense of humor or her sharp, observant mind. Clem also acts as a mirror to the other characters, revealing their contradictions and challenging their rigid ideologies.

Her dynamic with Mariel, in particular, reveals layers of tension, chemistry, and mutual growth, ultimately becoming a cornerstone of the emotional arc of the novel. Clem’s principled courage and commitment to healing, both physical and emotional, make her the moral center of the narrative.

Mariel Hartley

Mariel is portrayed as a disciplined, battle-hardened captain navigating the treacherous waters of legacy, expectation, and personal conflict. As the daughter of the infamous Robin Hood, she bears the weight of a legendary name and the burden of living up to her father’s vision for the Merry Men—a group that has evolved from romanticized outlaws to a military faction steeped in bureaucracy and suspicion.

Mariel’s outward coldness and obsession with control mask deep-seated insecurities stemming from a fractured relationship with her mother and a strained loyalty to her father. Her interactions with Clem begin in icy opposition, but Clem’s presence forces Mariel to reckon with her own rigidity and emotional detachment.

Over the course of Not for the Faint of Heart, Mariel undergoes a profound transformation. The revelation of her father’s manipulations and her mother’s exile prompts a crisis of identity.

Yet, her leadership qualities—rooted not in perfection but in fierce loyalty and adaptability—come to the fore. Mariel’s decision to democratize the leadership of the Merry Men rather than accept it by birthright encapsulates her evolution from a soldier shaped by others to a leader defined by her own convictions.

Her bond with Clem, laced with tension, tenderness, and mutual respect, becomes the novel’s emotional fulcrum.

Morgan

Morgan stands out as one of the most emotionally volatile and deeply scarred members of the resistance. Initially introduced as a rebellious youth with a surly demeanor, their complexity is gradually revealed through moments of intense vulnerability and moral courage.

Morgan’s history of trauma—particularly their past abuse by Lord Hanham—drives their impulsive behavior during the rescue mission, where they risk the mission’s success to enact personal revenge. This moment of defiance nearly causes disaster but also uncovers the emotional pain and desire for recognition that drives them.

Despite being temporarily expelled from the group, Morgan’s confession about their past and need to be seen invites compassion, particularly from Baxter and later Mariel. Clem’s kindness and care during Morgan’s inebriated state further cements their place within the found family of rebels.

Morgan’s arc is one of reclamation—reclaiming agency, voice, and a place among a community that both challenges and nurtures them. Their journey underscores the theme that resistance is not only about toppling external enemies but also about healing internal wounds.

Jack Hartley

Jack Hartley represents the shadow of idealism corrupted by power. Once a legendary figure at the heart of the Merry Men, he has become a cold and autocratic strategist whose vision for the rebellion has calcified into militarism.

Jack’s demeanor is one of calculated indifference—he dismisses Clem’s healing innovations, shows little warmth toward Mariel, and manipulates circumstances for perceived tactical gain. His estrangement from both his daughter and his former partner, Regan, underscores his inability to form genuine emotional connections.

Jack’s betrayal of Regan and his willingness to use Clem as a pawn reveal his prioritization of control over compassion. In the final stretch of the novel, his decline—both physical and ideological—is stark.

Grievously wounded and politically weakened, Jack’s offer to pass leadership to Mariel is not an act of generosity but a last-ditch attempt to preserve influence. His rejection by Mariel, who chooses a democratic process instead, marks a symbolic end to the era of his authority.

Jack functions less as a villain and more as a cautionary embodiment of resistance hollowed out by authoritarianism.

Rosie Sweetland

Rosie serves as Clem’s guardian and an early source of warmth, wisdom, and comedic levity. Though her screen time is limited, her influence looms large over Clem’s sense of right and wrong.

Rosie’s arrest at the hands of the Merry Men catalyzes the entire narrative, and Clem’s decision to take her place is rooted in deep loyalty and admiration. Rosie treats danger with characteristic cheek, using humor as a shield, yet it is evident that her past is more complicated than it first appears.

Her suspected affiliations with the Sheriff’s forces raise questions about survival, morality, and pragmatism in a world where allegiances are never black and white. Rosie embodies the idea that even the kindest figures have shadows, and her role acts as a narrative pivot, emphasizing that family—biological or chosen—is both a source of strength and vulnerability.

Josey

Josey is a lethal yet charismatic lieutenant whose sharp wit masks a pragmatic worldview shaped by warfare. His relationship with Clem is marked by teasing affection, which gradually turns into respect.

Though not as emotionally raw as characters like Morgan or Mariel, Josey provides levity and tactical clarity. He is a figure of balance within the group—never fully cynical, yet never fully idealistic either.

Through his eyes, we see the human toll of prolonged conflict and the subtle shifts in allegiance that occur when ideology is replaced by lived experience. His interactions with Clem, particularly during medical crises, allow for flashes of compassion that hint at a more nuanced inner life.

Baxter Scarlet

Baxter serves as the emotional bedrock of the rebel camp—a large, physically imposing man whose heart is even larger. His role as comic relief is undercut by his quiet moments of profound emotional intelligence.

Baxter comforts Morgan during their darkest hour, performs ceremonial rites for the dead with reverence, and stands by Mariel and Clem through chaos and uncertainty. His death is a pivotal emotional blow, shaking the foundation of the group and catalyzing a shift in their unity and urgency.

Baxter’s legacy becomes a guiding force for the group’s moral compass, representing kindness and loyalty in a world that often demands the opposite.

Regan

Regan, Mariel’s estranged mother, enters the narrative late but with explosive impact. A former revolutionary in her own right, Regan’s exile by Jack Hartley for questioning his authority reveals a recurring theme: the silencing of dissent in the name of order.

Regan’s idealism is tinged with self-interest—she allows Clem to be wounded protecting her and leaves without gratitude, showcasing a cold pragmatism that undermines her revolutionary veneer. Yet, she also plays a key role in dismantling Jack’s narrative, offering Mariel the painful truth about her family’s dysfunction.

Regan is a cautionary figure—brilliant but emotionally unavailable, principled but self-serving. Her presence deepens Mariel’s internal conflict and prompts the final, necessary rupture between father and daughter.

Frederic de Rainault

Frederic de Rainault begins as a detestable aristocrat—smug, privileged, and cruel—but evolves into something more complex. His duel with Mariel and later unexpected tenderness toward Clem complicate the binary of good versus evil that the rebellion often promotes.

Frederic’s actions hint at buried humanity, and his willingness to show kindness to an injured Clem suggests that redemption is possible even for the most unlikely figures. His presence in the novel reminds readers that individuals cannot always be judged solely by their affiliations; transformation, even fleeting, remains possible.

Kit

Kit, the gentle medic of the group, plays a quieter yet essential role. As someone who bridges the gap between Clem’s world and that of the Merry Men, Kit offers medical expertise and quiet support.

His emotional farewell to Baxter and his calm demeanor in chaotic situations anchor the group’s collective grief and healing. Kit embodies the ideal of care as resistance and reinforces the theme that healing—physical and emotional—is a revolutionary act in itself.

Themes

Disillusionment and the Loss of Idealism

Clem’s abduction and her subsequent interactions with the Merry Men force her to confront a painful discrepancy between myth and reality. Raised on tales of heroic outlaws standing up to tyranny, Clem expects camaraderie, moral clarity, and just rebellion.

Instead, she is faced with a fractured militia bound by paranoia, bureaucracy, and emotional coldness. The group’s actions—arresting innocent people, holding Clem as a political hostage, and operating under militarized hierarchy—strip away the romanticism she once held.

Mariel’s leadership, shaped by her desire to prove herself to her authoritarian father, contrasts starkly with the heroic legends of Robin Hood, revealing the grim, pragmatic demands of sustaining a resistance. Clem’s journey mirrors that of many disillusioned individuals whose ideals are challenged by the moral ambiguity and internal rot of revolutionary movements.

This theme is not merely about the external corruption of a cause but also about the internal recalibration required to continue fighting for something once believed to be pure. Clem does not abandon the idea of justice but instead begins to redefine it on her terms, grounded in compassion, pragmatism, and human decency rather than legends and lineage.

The Merry Men, in their current incarnation, represent how noble ideals can be co-opted by structure and ambition. Through Clem’s eyes, the reader is invited to question the sustainability of heroism in a world dictated by power and legacy, and whether true rebellion can exist without evolving its ethos.

Found Family and Emotional Resilience

Throughout Not for the faint of heart, the ragtag group of rebels forms a makeshift family marked by tension, humor, shared trauma, and reluctant trust. While they begin as Clem’s captors, the Merry Men gradually become entwined in her emotional world, offering support, sparring affection, and eventual loyalty.

Characters like Baxter, Josey, Kit, and even Morgan reveal depths of vulnerability, creating a contrast to their outwardly tough exteriors. This community forged under duress reflects the theme of found family, a particularly poignant counterweight to Clem’s increasing alienation from traditional structures of authority.

Mariel’s emotional arc also intersects here—her relationships are shaped by absence, expectations, and emotional withholding from both her parents. The bonds she forms with Clem and her comrades slowly chip away at her emotional armor.

The warmth of Underwood, their hidden base, offers a momentary reprieve where camaraderie feels genuine and earned. Moments of shared meals, songs, and confessions reveal how connection becomes a survival strategy.

Clem’s influence becomes catalytic—not by commanding, but by listening, healing, and showing compassion even when it is not deserved. In a world ruled by suspicion and violence, the rebels’ ability to form emotional ties—however imperfect—marks them as resilient.

Their found family does not erase pain or betrayal, but it becomes a space where healing is possible, and where leadership can emerge from mutual care rather than inherited power. The emotional safety net they create affirms the radical act of choosing love and support amid chaos.

Identity, Inheritance, and Leadership

Mariel’s arc is defined by her struggle with identity—both in the shadow of her legendary father, Jack Hartley (Robin Hood), and through her fractured relationship with her mother, Regan. Her leadership style is one of constraint, discipline, and emotional suppression, shaped by the constant need to live up to her father’s legacy.

Jack is a symbol of authoritarian charisma who demands obedience, while Regan, long estranged, represents idealistic rebellion. Caught between these two poles, Mariel’s identity becomes a site of conflict, performance, and gradual transformation.

Her interactions with Clem force her to confront what leadership can and should look like. Clem models a style rooted in empathy and honesty, which challenges Mariel’s sense of self-worth.

By the novel’s end, Mariel’s decision to reject inheritance in favor of a democratic vote reflects a monumental shift in how she perceives power. She no longer accepts leadership as a birthright but instead as a responsibility rooted in the community’s trust.

This thematic concern with identity also manifests in the internal struggles of other characters—Morgan’s outburst over being forgotten, Clem’s rejection of passive victimhood, and the group’s collective shift from soldiers to citizens. The theme interrogates how identity is not static but continuously shaped by relationships, choices, and the courage to reject the roles assigned by history and family.

Leadership, it suggests, must be earned not through legacy but through integrity, vulnerability, and service.

Moral Courage and Self-Determination

Clem consistently exemplifies the kind of courage that emerges not from grand gestures but from quiet, stubborn acts of defiance and care. Her insistence on telling the truth, even when it endangers her; her unwavering decision to treat the wounded, even those who hurt her; and her challenge to the rigid authority structures around her all underscore her commitment to moral self-determination.

She does not wait for permission to act justly. Whether rescuing Morgan, protecting Regan, or standing up to Jack, Clem’s actions demonstrate that real bravery lies in holding fast to one’s ethics when it is inconvenient or dangerous.

Her form of resistance is deeply personal—it doesn’t seek to dominate but to humanize. Mariel, too, undergoes a transformation that reflects this theme.

She begins as someone who sees vulnerability as weakness, but eventually comes to understand that moral courage includes the ability to admit failure, ask for help, and choose a path not dictated by fear or expectation. The novel suggests that real rebellion is not defined by breaking laws but by building better values, often at great personal cost.

Clem’s wounds, both physical and emotional, are worn as evidence of a life lived with purpose. Her actions make clear that heroism is not limited to those with swords or titles—it belongs to those who show up, care deeply, and insist on dignity for themselves and others, even in the face of overwhelming violence or betrayal.

Grief, Healing, and the Limits of Idealism

Baxter’s death and its aftermath mark a turning point in the narrative where the emotional stakes become undeniable. The collective mourning at the funeral highlights the rebels’ humanity, stripping away their soldierly personas and revealing the rawness of their grief.

Clem, who has always responded to pain by reaching outward, finds herself temporarily lost, both physically and emotionally. Her healing powers, so often used to mend others, are challenged by the realization that not all wounds can be closed.

The limits of her idealism come into sharp focus during this sequence—she cannot save everyone, and not every act of kindness is reciprocated. Regan’s cold indifference after being rescued by Clem crystallizes this painful truth.

Meanwhile, Mariel grapples with her father’s betrayal and her mother’s complicated legacy, forcing her to grieve not just for the dead but for the fantasy of a just, coherent family. The scene of Clem’s collapse from an arrow wound functions as both a literal and symbolic surrender—she cannot be the solution to everyone’s problems, and her survival is contingent on being saved in turn.

The novel uses grief not as a closing point but as a crucible through which healing and transformation can occur. It rejects easy redemption arcs or tidy resolutions, instead offering a realistic portrayal of how grief reshapes people and communities.

Clem and Mariel’s decision to move forward together, wounded but determined, becomes a final affirmation that healing is possible—not as restoration, but as resilience.