On Our Best Behavior Summary, Analysis and Themes

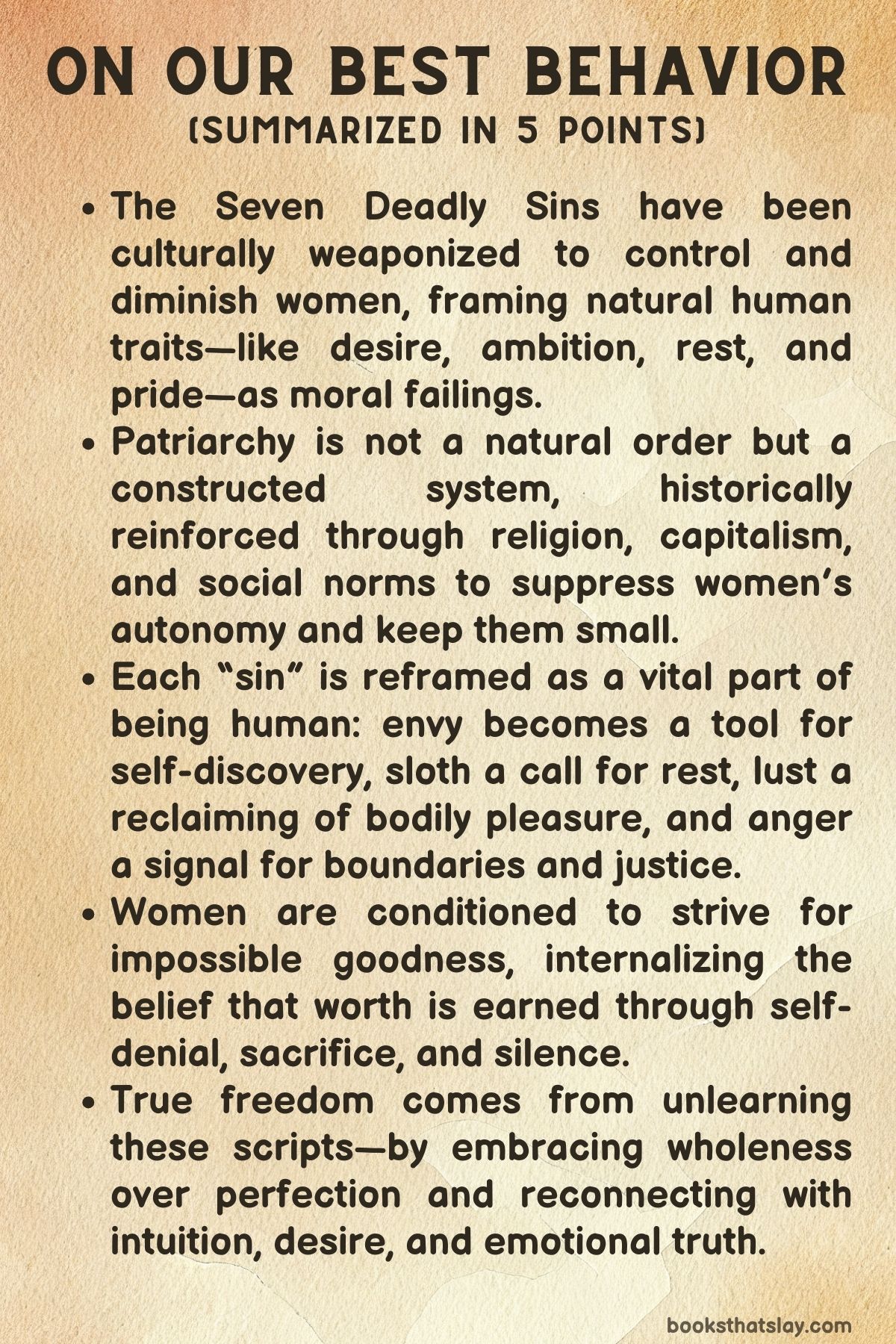

On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to Be Good by Elise Loehnen is a powerful cultural critique and personal reflection on how women have been conditioned to self-deny in the name of “goodness.”

Blending memoir, research, feminist theory, and spiritual inquiry, Loehnen traces how the Seven Deadly Sins—though not biblical—have been weaponized to suppress women’s desires, needs, and power. She explores how these “sins” have become tools for patriarchal control, shaping everything from our ambition and appetites to rest and rage. Ultimately, she urges readers to reclaim wholeness, not through perfection, but by honoring their full humanity.

Summary

In On Our Best Behavior, Elise Loehnen begins with a deeply personal moment of crisis. In late 2019, despite outward success, she was hyperventilating daily, overwhelmed by the pressure to be perfect. A therapist helped her uncover a deeply rooted belief: that if she could just be good enough, she’d be safe and loved. This became the seed of the book.

Her investigation led her to the Seven Deadly Sins—not biblical commandments, but moral frameworks institutionalized by patriarchal religion and culture. Loehnen argues these sins have been internalized by women as blueprints for a self-sacrificing, obedient life, far removed from authenticity or joy.

The book opens with a historical overview in “A Brief History of the Patriarchy,” examining how human societies moved from egalitarian structures to male-dominated hierarchies. As agriculture developed, women’s reproductive power became something to control. With monotheistic religions came male gods, female demonization, and moral codes that cemented patriarchal dominance. The Seven Deadly Sins became tools of social control, with female bodies and behaviors the target.

From there, each chapter explores one sin and how it has culturally programmed women to abandon essential parts of themselves.

In “Sloth,” Loehnen reveals how rest is viewed as immoral laziness for women. Conditioned by Protestant work ethics and capitalist demands, women feel compelled to overfunction—to never stop, never rest, never ask for reprieve. Being still is framed as failure, rather than necessary restoration. She reframes rest as radical resistance to burnout and erasure.

“Envy” explores how women are taught to suppress or feel ashamed of their desires. Instead of acknowledging envy as a signpost to what we long for, women are pushed into silent competition, judgment, and guilt. Loehnen suggests that when envy is honored, it becomes a guide to ambition and truth, not a flaw.

In “Pride,” she dismantles the belief that confidence in women equals arrogance. Women are taught to downplay their gifts, avoid the spotlight, and stay small. Pride has been cast as sinful self-promotion, but Loehnen argues it’s essential for living fully and being seen.

“Gluttony” delves into diet culture and bodily control. Women’s morality has become tied to thinness, self-denial, and control over appetite. Hunger—both literal and metaphorical—is suppressed to maintain societal ideals. Loehnen urges readers to reclaim hunger as natural, not shameful.

In “Greed,” the target is financial ambition. Women are praised for selflessness but discouraged from seeking wealth or asserting economic value. Money becomes a taboo topic, and dependence is normalized. Loehnen reframes financial clarity and desire as essential for autonomy and agency.

“Lust” examines sexual desire—how women are both objectified and shamed for owning their sexuality. Sensuality is policed through modesty rules and double standards. Loehnen calls for the reclamation of desire as sacred and life-affirming, rather than sinful or shameful.

“Anger” tackles emotional repression. Female anger is seen as unattractive, irrational, or dangerous. Women internalize resentment, which often manifests as anxiety or depression. Loehnen argues that anger is valuable data—signaling injustice and the need for boundaries. Reclaiming it is a path to liberation.

Finally, in “Sadness,” Loehnen explores the under-acknowledged grief and vulnerability women carry. Sadness is stigmatized and buried under toxic positivity, but Loehnen treats it as sacred—something to move through, not suppress.

In her conclusion, she reframes sin not as evil, but as “missing the mark”—a disconnection from self. She calls for balance, not perfection; alignment, not obedience. Through storytelling and insight, she invites women to release guilt, honor their inner compass, and step into full humanity—not by asking permission, but by claiming it.

Analysis and Themes

The Historical Construction of Patriarchy and Its Impact on Women’s Identity and Autonomy

One of the most critical themes in On Our Best Behavior is the historical construction of patriarchy and its long-lasting effect on women. The patriarchy, as Elise Loehnen explains, is not a natural system but one that has been deeply ingrained through centuries of cultural, religious, and political forces.

In the early stages of human civilization, societies were far more egalitarian, with women revered for their role in reproduction and care. However, the rise of agrarianism brought about a paradigm shift toward ownership and control, particularly over women, who were seen as property and reproductive assets.

This transition was further solidified by the advent of monotheistic religions, which reinforced male dominance by demonizing female power and by institutionalizing laws that reinforced women’s inferiority. The Seven Deadly Sins, originally created to regulate the moral behavior of people, were later co-opted to control women specifically, reinforcing ideas of sin and guilt related to their natural desires, needs, and behaviors.

The fear and suppression of these desires continue to manifest in modern times, shaping how women perceive themselves and how they are treated within a patriarchal society. This theme illustrates how patriarchal norms have been institutionalized and perpetuated by cultural myths, legal structures, and religious doctrines, leaving women in a constant state of self-surveillance and self-denial.

The Repression of Rest as a Moral Imperative and Its Detrimental Effects on Women’s Well-being

Another important theme explored in the book is the cultural weaponization of rest and how it has been linked to moral failure, especially for women. In Chapter 2, Loehnen critiques the concept of “sloth,” which has historically been framed as a cardinal sin.

The cultural narrative, particularly in Western societies, has perpetuated the idea that women, in their roles as caregivers, homemakers, and professionals, should constantly be in motion—producing, serving, and performing. This relentless expectation of constant productivity is rooted in capitalist and Protestant work ethics, where the idea of resting or taking a break is seen as laziness and failure.

This belief system has led to the internalization of guilt for women when they choose rest over work or caregiving, often resulting in burnout, anxiety, and self-neglect. Loehnen challenges this perception, calling for a radical rethinking of rest—not as a weakness, but as an essential act of reclaiming one’s humanity.

She posits that rest should be seen as a revolutionary act, a necessary step toward healing and self-care, particularly in a society that demands women to sacrifice their well-being in the name of others.

The Social Construction of Female Desire and the Stigmatization of Envy and Lust

Loehnen also tackles the cultural suppression of female desire, particularly in terms of envy and lust. In Chapter 3, she explores how envy, often dismissed as a negative and destructive emotion, is a suppressed signal of unmet desires or unacknowledged goals.

Women are conditioned to feel ashamed of their envy, and it is often misdirected toward other women rather than toward the systems that restrict them. Instead of seeing envy as a tool for self-discovery, women internalize it as a flaw, leading to competition, self-doubt, and feelings of inadequacy.

Loehnen argues that envy, when acknowledged and explored, can serve as a powerful tool for aligning oneself with true desires, helping women gain clarity about their needs and goals. Similarly, the concept of lust, as explored in Chapter 7, has historically been framed as dangerous and immoral when associated with female desire.

Women are often taught to be passive objects of desire, while men are encouraged to pursue and assert their own sexual agency. This has resulted in women being socialized to fear their own sexual desires and pleasures.

Lust has been demonized not only in religious contexts but also in cultural narratives, where women’s sexuality is often linked to shame, sin, or a loss of control. By denying women the autonomy to claim their desires and pleasures, society enforces a form of self-erasure and keeps women in a position of subjugation.

Loehnen argues that reclaiming lust as a natural, vital force of life—rather than something to be feared or suppressed—can help women reconnect with their full humanity and assert their rights to pleasure, autonomy, and sexual sovereignty.

The Pathologization of Emotional Expression: Anger, Sadness, and the Denial of Authentic Feelings

Loehnen also dives into the repression of emotional expression, particularly in women, who are taught to suppress feelings of anger and sadness. In Chapter 8, she highlights how women are socialized to avoid expressing anger, as it is seen as unattractive, unladylike, or even hysterical.

Anger, however, is a powerful signal that points to injustice, unmet needs, and violated boundaries. When women internalize anger instead of expressing it, the emotion can turn inward, leading to depression, anxiety, and physical ailments.

The cultural ideal of the “good girl” requires women to remain calm, accommodating, and peacekeeping, at the expense of their own needs and self-respect. Loehnen encourages women to embrace anger as an essential emotion, one that can guide them toward clarity, self-assertion, and justice.

In Chapter 9, the theme of sadness is explored, not as a weakness but as a profound emotional experience that is often repressed in both men and women. Women, in particular, are expected to be strong and caretakers of others’ emotions, while their own grief or sadness is marginalized or ignored.

This cultural expectation has led to what Loehnen calls “toxic positivity,” where sadness is either denied or suppressed in favor of an unrealistic, always-happy ideal. Sadness, according to Loehnen, is not something to overcome but an essential part of the human experience.

It provides an opportunity for healing, integration, and connection, allowing women to acknowledge and process their emotional wounds.

Reclaiming the Full Spectrum of Human Experience: From Suppression to Liberation

The overarching theme of On Our Best Behavior is the reclamation of women’s full humanity by confronting and questioning the cultural programming that has defined their desires, emotions, and actions as sinful or wrong. Whether it is the denial of rest, the suppression of ambition, or the demonization of emotional expression, the book argues that women have been culturally conditioned to reject essential parts of themselves in the name of being “good.”

By understanding the origins of these beliefs and challenging their legitimacy, women can begin to reclaim their autonomy, their desires, and their full emotional range. Loehnen advocates for a new understanding of goodness—one that is rooted in self-awareness, emotional honesty, and the integration of all aspects of the self, rather than in obedience, perfection, or self-sacrifice.

This process of self-reclamation, Loehnen suggests, is not only crucial for individual healing but for the transformation of society at large, enabling a more authentic, equitable, and integrated world.