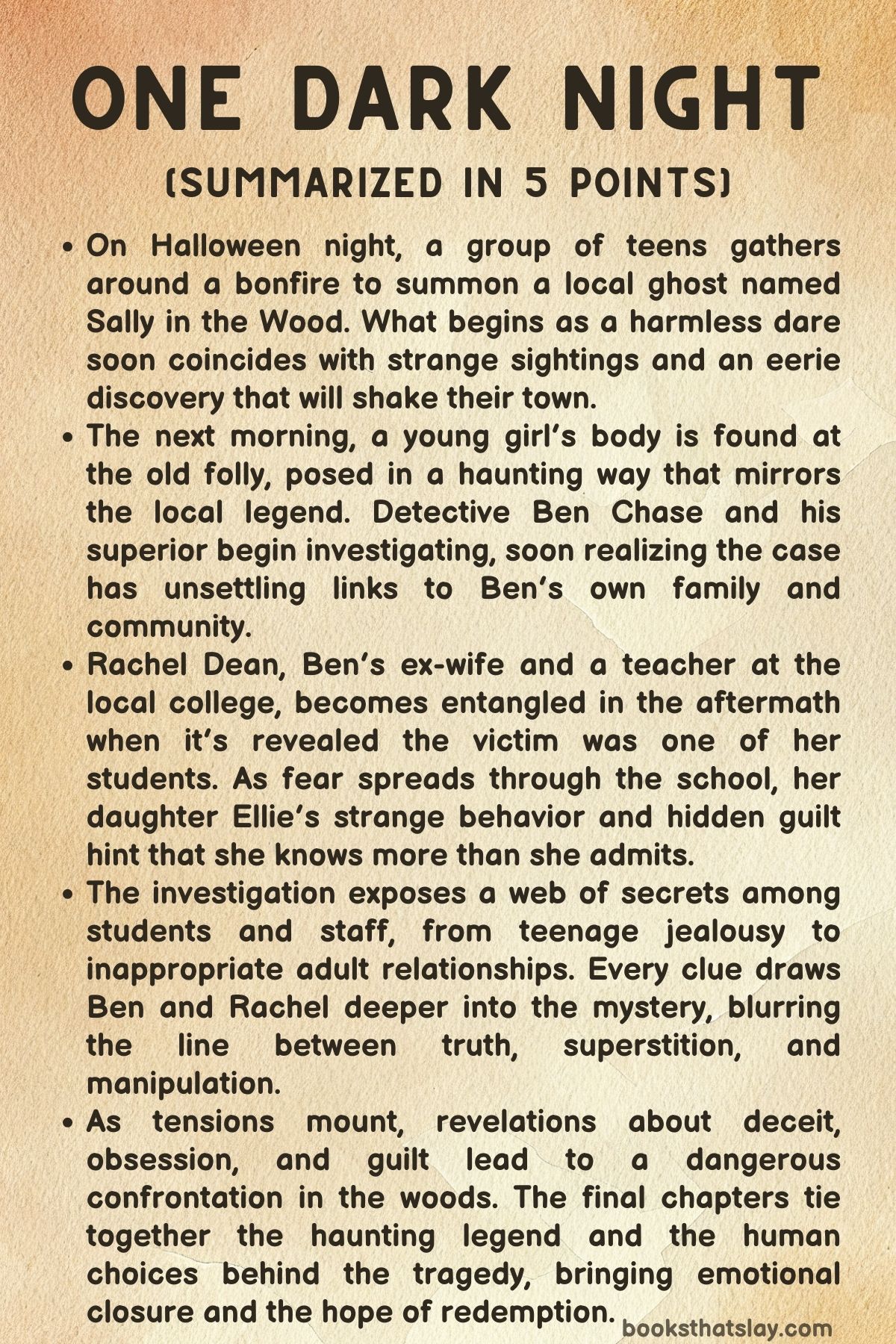

One Dark Night by Hannah Richell Summary, Characters and Themes

One Dark Night by Hannah Richell is a psychological crime thriller set in a small English town steeped in local folklore and buried secrets. The novel begins with a chilling Halloween legend and unravels into a murder mystery that exposes the dark side of human behavior, grief, and guilt.

Through multiple perspectives—detectives, teachers, parents, and students—it explores how lies, fear, and fractured relationships can twist truth into something deadly. At its core, the book examines the devastating aftermath of one fateful night when superstition, teenage recklessness, and adult failures collide, leaving a community to face the shadows it tried to ignore.

Summary

On Halloween night, a group of teenagers gathers in the woods near an old folly, retelling the haunting legend of Sally in the Wood—a ghostly bride said to have been murdered by her fiancé. As they use a homemade spirit board, strange things begin to happen, and one girl believes she sees someone lurking among the trees.

Hours later, John Slater, a taxi driver, drives home along the same forest road and swerves violently to avoid a white figure darting across his path. He survives the near crash, shaken but unaware that his sighting is tied to a tragedy about to grip the entire town.

At dawn, a troop of Girl Guides hiking through the woods discovers a girl’s body near the stone folly. She is dressed in white, her face partly covered by a grotesque bird mask, and words—PUNISH, DESTROY, REPENT—are painted on her arms.

The community is horrified, and Detective Sergeant Ben Chase and his superior, DCI Hassan Khan, begin investigating. The victim, later identified as Sarah Lawson, a student from Folly View College, appears to have been murdered elsewhere and staged deliberately at the site.

Meanwhile, Rachel Dean, a teacher at the same school and Ben’s ex-wife, notices police activity near the woods during her morning run. Her daughter Ellie, who attends Folly View, wakes up hungover and terrified, hiding bloodstained clothes and fragmented memories of the party the night before.

She suspects she might have witnessed or been involved in something terrible but keeps silent out of fear.

The investigation soon links Sarah’s death to the Halloween party attended by Folly View students. Philippa Easton, Sarah’s aunt, grows frantic when her daughter Olivia reveals that Sarah stayed behind at the party in the woods, wearing Olivia’s white lace dress and acting strangely.

When police confirm that Sarah is the victim, grief tears through the Easton family, and suspicion falls on Danny Carlisle, a local boy Sarah had been dating.

Danny tells detectives that the night spiraled out of control after his older brother, Connor, crashed the party with drugs. During a dare game called “Sally Says,” Sarah kissed Connor instead of Danny, leading to a fight.

Danny left in anger after seeing suspicious messages on Sarah’s phone, but he insists he didn’t harm her. His story adds to the confusion—Sarah was alive when he left, yet she ended up dead hours later.

As detectives work through conflicting accounts, Ben struggles to maintain professionalism. His daughter Ellie’s involvement in the party makes him a potential conflict of interest, but he hides this fact from his colleagues.

His personal life also frays as his partner, Chrissie, grows suspicious and distant, especially after learning that Rachel is still central to his thoughts and professional life.

Soon, Ellie is detained for questioning after her name surfaces in witness statements. Rachel is devastated as their home is searched by police, and Ben is suspended from the case.

Meanwhile, Rachel’s interactions with Malcolm Crowe, the creepy school caretaker and husband of the headteacher, grow increasingly disturbing—he’s caught snooping through Sarah’s confidential school records and making cryptic remarks about “naughty girls.

Despite suspension, Ben continues investigating privately. He discovers reports of a disheveled man living in the woods near a sealed cave, covered in markings similar to those found on Sarah’s body.

Following this lead, he uncovers the man’s hideout filled with graffiti echoing the same disturbing words: PUNISH, DESTROY, REPENT. When police arrive, they arrest a filthy vagrant who mutters that he “took care of her,” but Ben senses they have the wrong person.

Rachel, meanwhile, grows increasingly fearful after a near car accident and rumors about Malcolm spying on students. Two frightened girls claim to have seen Sally’s ghost at school, amplifying the sense of unease.

Then John Slater’s testimony about seeing a figure in white near the accident site adds a crucial clue—Sarah might have been running away from someone that night, not heading toward the folly as assumed.

The case takes a turn when Connor Carlisle calls Ben, saying he recognizes the “man in the woods” from television coverage—it’s Edward Morgan, the school’s art teacher. As suspicion shifts, Rachel recalls how Edward’s recent paintings eerily mirror the scene of Sarah’s death.

At school, Edward acts calm, teaching his students—including Ellie—before coaxing her onto his motorbike, promising to help her “confront her fears.

At the same time, Olivia Easton rushes into Rachel’s office, hysterical. She confesses that Edward once asked her to model for him and later began an inappropriate online relationship through a fake account.

When Sarah discovered the secret and threatened to expose him, Edward sent Olivia a message saying, “I’ll take care of her. ” Realizing the danger, Rachel contacts Ben and races to the woods with Olivia after learning Edward has taken Ellie there.

At the station, detectives interrogate Malcolm Crowe, who admits he followed the teenagers into the woods on Halloween to stop them from disturbing protected bats but also reveals that he saw Edward riding away with a girl that night. Meanwhile, digital forensics recover Facebook messages between Edward and Sarah, confirming he had been in contact with her before she died.

Ben realizes the wrong man was arrested—the killer is still free.

In the foggy woods, Edward leads Ellie up the trail to the folly, claiming they are facing her trauma by revisiting the place of fear. Rachel and Olivia arrive soon after, discovering Edward’s motorbike and following them up the path.

As Rachel shouts for Ellie, Edward insists on his innocence but grows increasingly erratic. When Olivia appears at the tower, chaos erupts—Edward falls during the struggle, badly injured, while Ben arrives just in time to find Ellie held hostage by Olivia with a knife.

Through calm negotiation, Ben persuades Olivia to speak. Overcome by guilt, she confesses that Sarah had catfished her, pretending to be Edward online as a cruel joke.

When Olivia discovered the deception on Halloween, she confronted Sarah at the folly, and in the heat of anger, pushed her. Sarah fell to her death, and Olivia fled, nearly being hit by John Slater’s car.

Terrified, she hid her involvement, letting the legend of Sally in the Wood take the blame.

Ben and Ellie manage to stop Olivia from taking her own life, and she is taken into custody. Edward survives his injuries and later admits his inappropriate behavior with Olivia, though not murder.

The truth finally emerges: Sarah’s manipulation, Olivia’s impulsive violence, and the adults’ failures to see danger led to the tragedy that shattered their town.

Weeks later, life begins to mend. Rachel and Ellie visit Edward in the hospital, where Ellie’s art project—exposing environmental corruption linked to the Eastons’ housing project—has gained attention.

New evidence halts the development, and corrupt figures in the community are removed from power. Olivia remains in youth detention, awaiting trial, while Ben and Rachel tentatively rebuild trust, united in their love for Ellie.

The novel closes as mother, father, and daughter walk together into the winter light, leaving behind the darkness of Sally in the Wood and the one night that changed everything.

Characters

Rachel Dean

As Head of Student Welfare at Folly View College, Rachel anchors the human core of One Dark Night. Her instinct is to protect first and judge later, which pulls her into a fraught balance between professional duty and maternal fear when Ellie becomes entangled in the investigation.

She is perceptive—quick to notice smoke on Ellie’s clothes, to read the tremor beneath teenage bravado, and to connect unsettling details like Malcolm Crowe rifling a confidential file or Edward Morgan’s boundary-crossing “mentorship. ” At the same time, Rachel’s past with Ben has left seams of hurt that resurface under stress, yet she retains the steadiness to compartmentalize, advocate for students, and run toward danger when Ellie is at risk.

Her arc charts a movement from uneasy powerlessness to active intervention, and by the end she reclaims authority over her world—professionally by safeguarding students and personally by reopening a door to family repair.

Ellie Chase

Ellie embodies the volatile mix of guilt, loyalty, anger, and fear that defines adolescence under pressure. She is creative and sharp, but also impulsive—sneaking back to the woods, hiding incriminating items, lashing out with vandalism.

Haunted by fragmented memories of the party, she tries on cynicism (“some people have a rotten core”) as a shield for shame and grief. Edward’s coaxing to “face” the scene nearly weaponizes her vulnerability, yet Ellie’s essential courage surfaces when it matters: she helps pull Olivia to safety, owns pieces of her truth, and channels chaos into an art project that exposes environmental harm, reclaiming voice and agency.

Across the novel she moves from self-protective secrecy to hard-won integrity, becoming a moral barometer for the adults around her.

Detective Sergeant Ben Chase

Ben is a detective caught between professional rigor and paternal terror. His credibility erodes the instant Ellie becomes a suspect, forcing him to confront old wounds—his sister’s death, a history of avoidance, and a relationship with Chrissie built on escape rather than healing.

Even when suspended, his investigative mind never stops, and his instincts prove right about the cave and the misdirection around the initial arrest. Ben’s defining tension is control versus care: the job demands detachment, fatherhood demands partiality.

He fails at pure objectivity but succeeds at humanity, talking Olivia down and prioritizing life over blame. The closing suggestion of reconciliation with Rachel signals growth: not triumph, but a humbler steadiness rooted in accountability.

Olivia Easton

Olivia is written as both victim and perpetrator, a teenager destabilized by grief, humiliation, and the cruel alchemy of online deception. She loves Sarah fiercely, then learns the romance that buoyed her—messages she believed were from Edward—was a catfish orchestrated by Sarah.

The betrayal mutates love into rage; their confrontation turns fatal in a split-second shove. Olivia’s subsequent spiral—threats, the knife, the cliff-edge—reads as trauma made kinetic, not wickedness.

Yet she also shows conscience and despair, ultimately saved by Ben and Ellie. Her arc exposes how desire for validation can be exploited and how adolescent emotions, when cornered by secrecy and shame, can erupt into catastrophe.

Sarah Lawson

Sarah is the novel’s absent center, a magnetic girl whose death reorganizes the community. In life she is complicated: charming and kind in Olivia’s memory, but also manipulative, catfishing her cousin and stoking jealousies.

The words painted on her arms—PUNISH. DESTROY. REPENT. —mirror the punitive mood of a town hungry for monsters.

Sarah’s choices spring from unhealed trauma and a need for control—a way to script attention and affection on her terms. In death she becomes legend, conflated with the local ghost story and instrumentalized by adult agendas; in life she was a teenager improvising power in risky ways.

The tragedy is not only that she dies, but that the messy truth of her humanity nearly gets erased by myth.

Edward Morgan

Edward straddles ambiguity for much of One Dark Night: a charismatic art teacher, a supposed watcher in the woods, a man whose professional boundaries crumble into emotional entanglements. He encourages vulnerable students to “confront” fear, but his influence slides toward manipulation, framed by secretive messaging and that staged ride to the folly with Ellie.

Even when he’s not the killer, he embodies the danger of adult authority that mistakes fascination for mentorship. His later injuries and willingness not to press further charges suggest contrition or exhaustion more than redemption.

Edward personifies how art, intimacy, and power can blur—and how those blurs endanger young people.

Malcolm Crowe

The caretaker is a figure of misdirection and unease—seen roaming at night, parroting moralistic lines about “naughty girls,” and violating privacy by snooping through files. His presence amplifies the Gothic undertow of the campus, yet his motives prove smaller and pettier than the aura suggests, tied to surveillance, irritation at student antics, and bat-protection pretexts.

Malcolm illustrates how suspicion attaches to the odd and the elderly in a panicked community, and how institutional spaces can harbor quiet abuses that aren’t headlines but still corrode trust.

Margaret Crowe

As headteacher and Malcolm’s spouse, Margaret projects control in press conferences and assemblies, managing optics while staff and students quake. She is competent but image-conscious, announcing an arrest prematurely and pressuring the school machine to keep running.

Margaret is less a villain than a study in administrative reflex: stabilize, contain, communicate. In crisis, her priority is institutional reputation, and that tension with student welfare lets the novel question what “duty of care” looks like when the cameras arrive.

Christopher Easton

Christopher is power in a bespoke suit—anxious about reputation, property values, and the Folly Heights development. Grief for his niece curdles into aggression and scapegoating; he threatens Ben and seems more wounded by public backlash than by loss.

He’s not the architect of the crime, but he animates the social climate that seeks tidy villains and swift punishment. Christopher’s arc critiques how wealth can bend communal narratives, turning tragedy into a public-relations problem to be suppressed rather than a wound to be tended.

Philippa Easton

Philippa is a mother pulled between propriety and panic, medicated sleep and morning-after dread. She is less forceful than Christopher, more susceptible to the fog of grief and the urge to keep the family’s facade intact.

Her role underscores how domestic spheres accommodate public scandal—closing ranks, smoothing edges, and hoping silence will outrun truth.

DCI Hassan Khan

Khan is procedure personified: he suspends Ben appropriately, reins in speculation, and redirects the team when the investigation veers after Malcolm. His steadiness serves as an ethical scaffold for the case.

He’s not heartless—he listens and recalibrates—but he insists justice must be structurally fair, not emotionally satisfying, modeling the discipline the story’s panic keeps trying to unseat.

DC Fiona Maxwell

Maxwell is the grindstone investigator, patient in interviews and methodical with digital evidence. Her reading of Danny Carlisle balances empathy with skepticism, and her retrieval of Sarah’s phone data becomes the hinge that exposes the Edward–Sarah link and unseats Malcolm as suspect.

She represents the quiet competence that actually cracks cases while louder personalities clash.

Danny Carlisle

Danny is the wounded boy left behind—jealous, impulsive, and humiliated when Sarah kisses his older brother in a dare. He’s quick to anger but ultimately truthful about leaving the scene, and his bruises read as the cost of masculine posturing in a toxic peer ecology.

Danny’s pain is real, yet he refuses the slide into blame; his presence reminds us that teenage cruelty often grows in the soil of insecurity rather than malice.

Connor Carlisle

Connor is swagger without responsibility, a catalyst who brings drugs, mocks boundaries, and enjoys the spectacle. He doesn’t kill Sarah, but he helps set the emotional temperature to boiling and later throws out half-truths that muddy the investigation.

Connor is the ambient threat of a culture that trivializes consent and treats young women’s vulnerabilities as entertainment.

John Slater

The taxi driver is a witness who doesn’t know he’s a witness, his near-miss with the “white figure” first rationalized away as an owl or deer. His recollection later provides a crucial vector of movement through the woods and offers the story a moral footnote about hesitation, fear, and ordinary people’s roles in extraordinary events.

John’s small act—speaking up—helps reassemble the night’s timeline.

Diana Lawson

Diana’s identification of Sarah gives the narrative its rawest grief. Her recognition by a birthmark, not a face, strips away sensationalism and returns us to the reality of a mother and a daughter.

Diana doesn’t drive the plot, but the dignity and devastation of her scene insists that behind every campus rumor and news blast is a family with a hole in it.

Chrissie

Chrissie is the almost-family Ben has tried to build on unstable ground. She is decent and hopeful, pregnant and trying to be supportive, but her relationship with Ben bears the marks of rebound and secrecy.

Chrissie’s presence forces Ben to confront the cost of avoidance; she is the human measure of whether he will grow or loop the same mistakes.

Themes

Folklore, Superstition, and the Power of Stories

From the first scene around the bonfire, One Dark Night shows how a local legend can leak into ordinary life and start steering choices, perceptions, and even police work. “Sally in the Wood” is not just a campfire tale; it is a script that teenagers, parents, teachers, and detectives keep consulting to make sense of what they fear.

The legend supplies props—the white dress, the folly, the road with its history of crashes—and a ready-made cast of sinners and victims. Once that script is invoked, coincidence starts to look like fate, and pranks begin to resemble ritual.

Ben Chase senses the danger of this framing when early interpretations lean toward the monstrous unknown, yet even he is pulled toward the pattern because the details rhyme so neatly with the myth. The community’s need for a moral story accelerates suspicion and cements an atmosphere where sightings, whispers, and symbols carry more weight than timelines and forensics.

This is how the jar on a makeshift spirit board and a staged body painted with commandments can narrow the range of what people are able to imagine about the truth. The book uses the legend as a feedback loop: teenagers perform it to thrill each other; adults interpret events through it to calm their own anxiety; the police and school leadership, under pressure, treat it as cultural context that seems to explain motive.

In the end, the tragedy does not originate in the supernatural; it grows from human choices, desires, and failures. Yet the legend still matters, because it gives form to fear and supplies a vocabulary of punishment and repentance that certain characters exploit.

The story thus becomes a caution about stories themselves—how they clarify, but also how they blind.

Adolescence, Performance, and the Hazards of Belonging

The teenagers in One Dark Night are constantly on stage—at the party, on social media, in classrooms—and much of the danger comes from performance tipping into recklessness. Dares, costumes, drug-fueled bravado, and the thrill of filming everything turn a woodland gathering into a pressure cooker.

Sarah’s white dress is not only a nod to the legend; it is an outfit chosen to be seen, to control the gaze of others, and to play with expectations. Ellie’s hazy recollections, smeared with smoke and blood, capture how quickly identity blurs when a crowd is trying to outdo itself in daring and cruelty.

The game “Sally Says” is a perfect emblem: it repackages obedience and humiliation as fun, normalizes escalation, and rewards the boldest display. Online, the same dynamics operate with higher stakes.

Catfishing weaponizes the desire to be desired, turns trust into a trap, and collapses the boundary between private and public selves. The teenagers measure each other’s worth through screenshots, emojis, and rumors in a system that never forgets and seldom forgives.

Even remorse becomes a kind of performance when students craft statements for administrators and police. The novel gives these moments emotional density by showing how quickly a dare can become a confession, and a joke can become evidence.

Belonging, in this world, means reading the room faster than your peers and moving with a current that punishes hesitation. The tragedy exposes the cost of that economy: secrets multiply, truth fragments into curated snippets, and a single shove—meant to assert control in a volatile hierarchy—produces consequences no one can rewind.

Family Fracture, Care, and the Work of Responsibility

The triangle of Ben, Rachel, and Ellie anchors One Dark Night in the domestic sphere, where care is both an instinct and a discipline. Their family has been through divorce, grief, and new relationships, and the crisis arrives at an awkward moment of transition as Ben’s partner is pregnant and Rachel is guarding a fragile stability.

The investigation forces the adults to act as parents first and professionals second, yet their roles keep colliding. Ben’s skills as a detective become liabilities when they conflict with the obligation to protect his daughter, and Rachel’s position at the school complicates her duty to confidentiality and student welfare.

The novel examines how responsibility is not abstract; it is made of small choices—who gets a phone call, who is informed about a search, who receives the benefit of the doubt. Ellie’s secrecy and anger are not treated as simple teenage rebellion but as the language of a child navigating loyalty to both parents while fearing condemnation from each.

The possibility of reconciliation emerges not through grand declarations but through coordinated action under pressure: racing to the folly, talking someone down, attending medical appointments, gathering the courage to admit past mistakes. Responsibility, the book suggests, is not a static trait; it is the willingness to keep showing up when shame, exhaustion, and resentment would be easier paths.

In this sense the family narrative is a counterpoint to the legend’s cycle of punishment. Where the legend imagines balance restored through retribution, the family reaches for repair through presence, truth-telling, and the slow, unglamorous labor of trust.

Power, Grooming, and Institutional Failure

Adult authority in One Dark Night ranges from benevolent to predatory, and the boundary between mentorship and manipulation is repeatedly tested. Edward Morgan’s attention to students begins with the language of encouragement—modeling for art, special interest in talent—and migrates toward secret messages and emotional dependence.

The grooming does not announce itself as evil; it hides in praise, opportunity, and the thrill of being chosen. Olivia’s vulnerability is not weakness; it is the human hunger for recognition, amplified by adolescence and a high-pressure school.

The book is unsparing about institutional gaps that allow this to happen. Policies exist, but they can be bypassed by charisma, professional reputation, or simple naïveté from colleagues who do not want to imagine the worst.

Malcolm’s surveillance, dressed up as guardianship or environmental concern, reveals a parallel misuse of proximity to young people. The institution’s duty of care falters in public messaging as well, with premature announcements and reputation management competing with the need to listen, investigate, and protect.

This is not a story where one villain explains everything; it is about how systems make room for harm by rewarding results, overlooking boundary crossings, and treating whispers as nuisances rather than signals. The hardest scenes are those where the language of support is indistinguishable from the techniques of control.

The novel pushes readers to ask uncomfortable questions: How do we design oversight that is more than paperwork? How do we teach young people to name grooming without expecting them to carry the full weight of policing it?

And how do colleagues learn to treat oddities in behavior as clues that deserve attention rather than gossip?

Class, Image, and the Politics of Place

The Easton family’s development plans, the billboard, and the polished language of civic improvement pull One Dark Night into a contest over land, status, and narrative control. The housing project is marketed as progress, a boon to the community, and a signature achievement for a local elite.

Yet progress arrives with traffic, ecological stress, and the quiet silencing of those who live closest to its costs. Christopher Easton speaks in the idiom of reputation—investments, optics, damage control—treating tragedy as a public relations event to be managed.

The result is a split in town life: one faction wants tidy explanations and swift justice; another worries about what is being bulldozed, literally and figuratively, to maintain that image. Ellie’s protest art and the revelations about endangered bats expose the brittle underlayer of the sales pitch.

The book suggests that when a place is branded, it is easier to ignore the messy parts of its history, including legends that warn about violence and routes that have already claimed lives. Class operates here as a buffer against scrutiny; certain homes, cars, and surnames generate deference that slows enforcement and skews suspicion.

Conversely, working-class kids like the Carlisles are quicker to be read as trouble, their bruises translated into guilt rather than evidence of vulnerability. The woods themselves become a contested asset: amenity for brochures, obstacle for developers, refuge for those trying to hide from the gaze of respectable society.

By staging the climax at the folly—an architectural vanity project from another era—the novel shows how the built environment memorializes hierarchy while pretending to be merely picturesque.

Guilt, Truth, and the Uneasy Shape of Justice

The investigation in One Dark Night is a study in how guilt can be felt, assigned, and misread. Nearly everyone feels complicit in some way: Ellie because of the fight and her silence, Olivia because of the confrontation that led to the fall, Ben because of divided loyalties and shortcuts taken under stress, the school because warning signs were minimized.

The police process, pressured by fear and expectation, leans toward a clean culprit, yet the truth that surfaces is messier. The painting of words on the body, the staged mask, the witness reports of a watcher—these artifacts promise certainty but actually multiply interpretations.

When the responsible party is revealed, the category of murderer does not fit easily; the event is the endpoint of manipulation, humiliation, jealousy, and a single violent push. The novel resists simple moral closure, not to excuse harm, but to show that punishment cannot repair what community negligence and private cruelty set in motion.

Justice becomes less a verdict than a set of commitments: to name what happened without theatrics, to confront the systems that enabled it, and to carry forward care for the living. Even Sarah is given a complicated portrait—her catfishing is not framed as pure malice but as behavior shaped by trauma and an appetite for control that masked vulnerability.

The final pages suggest that the best version of justice is the refusal to let legend write the ending. Instead of sacrifice at the tower and a curse satisfied, the book offers an image of a family choosing to keep going, a community acknowledging what it ignored, and a recognition that truth often lives in the gray spaces institutions prefer not to see.

Landscape, Environment, and Moral Geography

The setting is not background in One Dark Night; the woods, folly, caves, and twisting road form a moral geography that characters navigate at their peril. The landscape records every human decision: graffiti commands on cave walls echo a culture of judgment; a sealed entrance that can be opened with a simple tool speaks to how thin our barriers really are; the bend in the road where accidents happen remembers those who did not make it home.

The presence of bats, and the legal protections they trigger, becomes a hinge for the plot and a reminder that nonhuman life compels accountability in ways human institutions evade. The environment pushes back against development plans and against the tidy storylines adults prefer.

Fog hides and reveals at crucial moments, a physical analogue for confusion and revelation in the investigation. The folly, a structure built to be looked at rather than used, becomes the most functional building in the story precisely because it concentrates attention; people are drawn there to test courage, declare intentions, and enact fantasies about punishment and absolution.

The woods offer sanctuary to the frightened and cover to the predatory, showing that safety is relational rather than inherent. Characters choose paths—literal trails and social routes—that announce their values: secrecy or openness, domination or care, quick gain or long stewardship.

By the end, the landscape has acted upon the people as much as they have acted upon it, halting a construction project, preserving a species, and insisting that the community reorder its priorities. The setting thus serves as a quiet judge, asking whether those who claim love for their town are willing to honor the place beyond marketing slogans and ghost stories.