One Good Thing Summary, Characters and Themes | Georgia Hunter

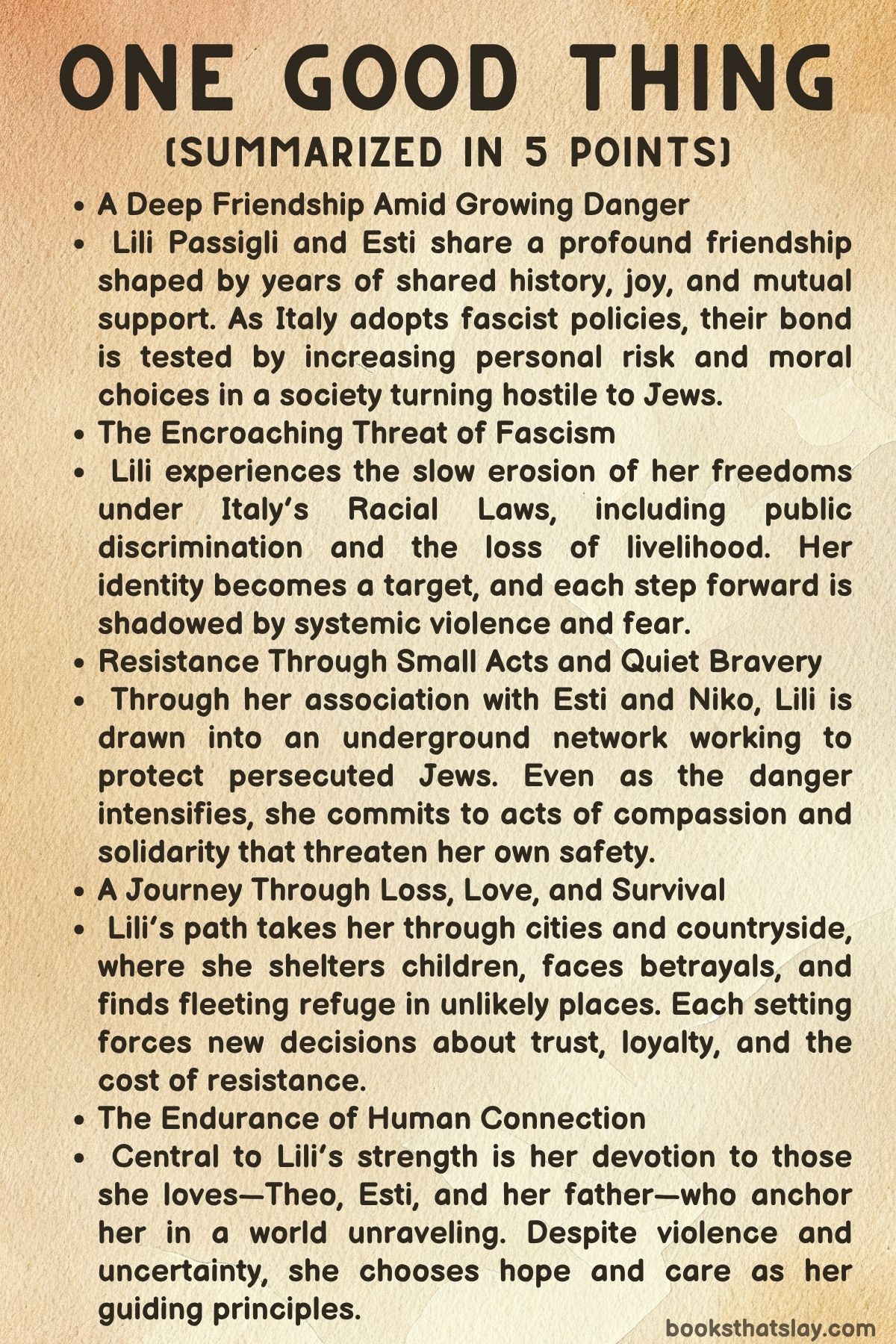

One Good Thing by Georgia Hunter is a moving novel set during the rise and fall of fascist Italy in World War II. The story follows Lili Passigli, a Jewish woman whose life is gradually dismantled by the forces of antisemitism, war, and resistance.

Through her unbreakable friendship with Esti, an underground activist, and her evolving bond with a child named Theo, Lili is drawn into the heart of the resistance effort across Italy. As persecution intensifies, Lili’s choices are shaped by loyalty, fear, and love. The novel, based on real events, honors quiet bravery and resilience in the face of unimaginable threat and grief.

Summary

The story of One Good Thing begins with a desperate escape: Lili Passigli is running through the woods during World War II with a young boy, dodging gunfire. This jarring scene sets the emotional and political stakes that shape the rest of the book.

The narrative then rewinds to quieter, though no less significant, moments. Lili is present at the birth of Theo, the son of her best friend Esti and Esti’s husband, Niko.

Their tight-knit friendship and growing worries over Niko’s secretive behavior are foregrounded against the backdrop of Mussolini’s tightening grip over Italy.

Through flashbacks, we learn how Lili and Esti met at university, formed an immediate bond, and built a chosen family in an increasingly hostile environment. Niko’s secretive work is soon revealed: he collaborates with Delasem, an underground organization helping Jews escape persecution.

This discovery brings both admiration and terror into Lili’s life, as she realizes how much danger surrounds them. Her trip to Bologna to visit her father, Massimo, highlights her vulnerability.

They attend a film that turns out to be virulently anti-Semitic, an experience that crystallizes the slow erosion of their safety and dignity under Fascist rule.

Despite Massimo’s optimism, the Racial Laws imposed by the regime increasingly restrict Lili’s life. A getaway with Esti to Rimini results in public humiliation and threats of arrest when they are denied lodging due to Lili’s Jewish identity.

Their argument about whether to protest or stay safe reveals their different approaches to surviving in a fascist world. The situation grows worse as a synagogue is desecrated on the eve of Rosh Hashanah.

Niko reacts violently, nearly executing a Fascist soldier, which propels him into hiding.

The narrative shifts to Ferrara in 1941. Esti, now on the run, arrives at Lili’s home with Theo in tow.

Niko has fled to Greece to help his family, leaving Esti to continue his work with Delasem. She admits to forging documents for Jews using fake Aryan IDs.

Lili, torn but loyal, agrees to shelter Esti and Theo. Over time, they move to Nonantola and begin working with Villa Emma, a refuge for orphaned Jewish children smuggled from across Europe.

While Esti handles forged documents, Lili helps teach and care for the children. Niko’s letters from Salonica become sparse, and the radio brings news of atrocities in Greece, escalating Esti’s worry.

Mussolini’s downfall brings temporary hope in 1943, but it’s quickly dashed when German forces begin occupying Italy. Esti, Lili, and their allies help smuggle the Villa Emma children into hiding, placing them in homes and churches across the countryside.

The villa is raided soon after. Esti is then recruited for high-level forging operations in Florence.

Lili joins her with Theo, and they stay with Massimo. The city, once a refuge, is now full of fear.

Esti works with Cardinal Dalla Costa, producing false documents to protect Jews from arrest. She eventually invites Lili to join the effort, symbolizing her deep trust.

The journey intensifies as Lili and Theo, now fugitives, flee southward through war-torn countryside. Along the way, they encounter both danger and unexpected allies, such as Gino Bartali, the cycling champion who helps smuggle them to safety.

They find temporary refuge at a convent and later with a farming couple, Giovanni and Luisa, where Theo finds a moment of happiness with a lamb he names Lucignolo. Yet danger is never far, and they are forced to leave again, this time passing through German-occupied towns and relying on clandestine networks of partisans.

They eventually join a band of rebels in the forest, where they meet Matilde, another Jewish woman hiding and fighting. She reveals horrific truths about the extermination camps.

Their respite is short-lived, as their camp is attacked. After Theo is injured, Lili seeks help and finds sanctuary in a small hospital before finally reaching Rome.

There, she delivers a mysterious package on behalf of the resistance. She and Theo are given shelter by a nun, and for a brief moment, they experience a quiet life amid the city’s ruin.

Theo calling Lili “Mama” solidifies their emotional bond.

As the war nears its end, Lili returns to Bologna and is reunited with her father. Their shared survival is a fragile joy tempered by unspoken grief.

She tries to preserve a sense of normalcy for Theo, celebrating his birthday and waiting for news about Esti, who remains missing. The liberation of Auschwitz brings with it horrifying images, but no answers.

Then, a letter from Thomas, the American soldier Lili once met, rekindles hope and possibility. When he returns in person and proposes a new life in America, Lili is torn.

Haunted by loss and reluctant to abandon her homeland and Esti’s memory, Lili seeks solace at her mother’s grave. There, she confronts her grief fully.

Esti’s diary, which Lili reads at last, reveals her final wishes: that Lili be Theo’s guardian, a message that affirms Lili’s role and the future she can offer him. With that blessing, she accepts Thomas’s proposal.

The book ends with Lili, Theo, and Thomas boarding a ship to New York. Though the war has stolen much, what remains is a sense of resolve and forward motion.

Lili leaves Italy not as someone who has escaped, but as someone who carries the memory of those lost, the weight of survival, and the quiet strength of love that endured through one of history’s darkest hours. One Good Thing closes on the promise of healing—not from forgetting, but from remembering and still choosing to live.

Characters

Lili Passigli

Lili Passigli is the emotional and moral center of One Good Thing. A Jewish woman caught in the tightening grip of fascist Italy, Lili’s character is one of extraordinary emotional depth and resilience.

She begins as someone anchored in intimate friendships and familial bonds, finding solace and strength in her relationship with Esti and her father, Massimo. Initially hesitant to become involved in overt acts of resistance, Lili’s journey becomes one of gradual moral awakening.

Her nurturing instincts are most powerfully expressed through her care for baby Theo, which deepens into maternal devotion and fuels her courage in increasingly dangerous circumstances. Lili’s sense of duty evolves beyond family into broader acts of resistance—teaching Jewish children in hiding, safeguarding false identities, and ultimately navigating the perilous route to Rome.

Her growth is measured not in grand heroic acts, but in her quiet, persistent choices to protect, endure, and love despite unspeakable risk. Even in the face of grief—over Esti’s presumed death, the ravages of war, and the loss of her homeland—Lili’s determination to rebuild a life with Theo is a testament to her fierce will to survive and preserve humanity.

Her eventual decision to emigrate to America with Thomas signals not an abandonment of the past, but a commitment to carry it forward with grace and renewed hope.

Esti

Esti is Lili’s best friend and an unforgettable force of nature in One Good Thing. From their early days as university students to their shared life during the war, Esti exudes charisma, intelligence, and a fearlessness that stands in stark contrast to Lili’s more measured temperament.

A skilled photographer, Esti becomes a linchpin in the Jewish resistance network, forging false documents, transporting children to safety, and risking her life countless times. Her marriage to Niko is tender but fraught with the pressures of war, and she often finds herself navigating the emotional weight of his absence, his danger, and her own clandestine work.

Esti’s unwavering moral compass and sense of justice drive her into ever riskier roles, even when she is physically and emotionally exhausted. She does not bend in the face of danger—whether confronting bigoted hotel staff, aiding orphaned children, or forging papers under the Nazi nose in Florence.

Through Esti’s diary and her final entrusting of Theo to Lili, we understand the profound love and trust she places in her friend. Her presumed death leaves a void, but her bravery and vision live on through Lili and Theo.

Esti represents the kind of fierce loyalty, bravery, and moral conviction that war both demands and immortalizes.

Theo

Theo, though just a child during the events of One Good Thing, becomes a powerful emotional symbol of innocence, survival, and legacy. Born at the novel’s start to Esti and Niko, Theo is at first a fragile, vulnerable life in a collapsing world.

But as the story progresses, his presence galvanizes Lili’s purpose and provides moments of light amid encroaching darkness. His needs, fears, and affections shape Lili’s decisions, whether it’s hiding with villagers, trudging through forests, or facing down checkpoints.

Theo is a silent witness to trauma—the raids, the flight, the hunger—but he is also a source of joy and grounding. When he names a lamb Lucignolo, or when he calls Lili “Mama” in Rome, we see how deeply he has come to rely on her and how much she has become his world.

His emotional evolution reflects the scars of war on children, yet his enduring spirit and capacity to love show that the future, while marred, is still possible. In the end, Theo symbolizes the continuity of love across loss, and his bond with Lili is the most enduring “good thing” the title evokes.

Niko

Niko is a complex, often absent, yet pivotal character in One Good Thing. As Esti’s husband and a committed member of the resistance, he is both a source of admiration and sorrow.

His clandestine work with Delasem and efforts to help Jews escape from Greece to Italy place him in grave danger, forcing him into hiding and separation from his family. Though his presence in the narrative is largely indirect—through letters, memories, and Esti’s grief—his choices have a profound impact on the trajectory of both Esti’s and Lili’s lives.

Niko’s character embodies the moral burden of action during wartime. He is not perfect—his secrecy, the risks he imposes on Esti, and his silence during long stretches strain their relationship—but he is deeply principled.

His courage and commitment to justice mark him as a quiet hero whose sacrifices echo long after he disappears from the story. The weight of his absence underscores the personal costs of resistance, and his memory remains a haunting presence in Esti’s arc and a reminder of the uncertain fates of countless others.

Massimo

Massimo, Lili’s father, serves as an anchor of familial love and quiet dignity in One Good Thing. A widower clinging to the memory of his wife Naomi and the traditions of his Jewish heritage, Massimo is a gentle, philosophical presence amid the chaos.

His relationship with Lili is marked by warmth and shared memory, and he often seeks to shield her from the full force of political reality, even as danger encroaches. His initial faith in Italy’s ability to return to normal is touching, if naive, and reflects a generation’s reluctance to believe the full horror of fascism.

Over time, he adapts—accepting false identity papers, surviving alone in Florence, and ultimately encouraging Lili’s decisions, even those that take her far away. His health becomes increasingly fragile, yet he never loses his emotional acuity.

In their final reunion, his blessing of Lili’s new life with Thomas and Theo is deeply moving, emblematic of love’s persistence even in broken times. Massimo represents the quiet endurance of memory, the lasting bonds of family, and the moral wisdom that carries forward even when the world collapses.

Thomas

Thomas is the American soldier who brings a quiet sense of hope and renewal into Lili’s war-torn life in One Good Thing. Though his appearances are relatively brief, they are emotionally resonant.

He first enters Lili’s world during a moment of transition and gradually becomes a symbol of possibility—a future not defined by war, secrecy, or fear. Thomas is kind, attentive, and respectful of Lili’s grief and trauma.

His letters are light-hearted yet thoughtful, and his relationship with Theo reveals a natural tenderness. When he proposes that Lili and Theo come with him to America, his offer is not just romantic—it’s an invitation to a different life, one shaped by peace and promise.

Lili’s struggle to accept his proposal reflects her internal conflict between honoring her past and embracing an unknown future. In the end, Thomas becomes a vessel for healing, not by erasing what came before, but by helping Lili see that she can carry her memories and love forward into a new beginning.

Matilde

Matilde, introduced later in One Good Thing, is a powerful character whose fierce pragmatism and bravery offer Lili a mirror of what female resistance looks like under extreme circumstances. A fellow Jew living among partisans in the woods, Matilde is deeply scarred by knowledge of the camps and the loss of her people.

She has no illusions left about the nature of the enemy, and her revelations to Lili about the extermination camps inject a chilling clarity into the narrative. Despite her hardened exterior, Matilde is capable of deep loyalty and compassion.

She accepts Lili and Theo into her circle, helps guide their journey, and ultimately encourages their survival. Her parting with Lili is filled with mutual respect and unspoken sorrow, knowing they may never see each other again.

Matilde’s presence is brief but potent—a reminder of the many women who resisted, endured, and shaped the course of history from the margins.

Giovanni and Luisa

Giovanni and Luisa, the farmer and his wife who temporarily shelter Lili and Theo, exemplify the quiet courage and decency of everyday Italians who risked everything to help persecuted Jews. Their home offers a moment of warmth, normalcy, and recovery in the midst of Lili and Theo’s long, traumatic journey.

Giovanni’s calm, grounded demeanor and Luisa’s maternal care underscore the importance of small acts of kindness during times of widespread cruelty. Their choice to help—despite the risk of German retaliation—adds a layer of moral humanity to the broader picture of resistance.

Though their role is small, it is profoundly felt, representing the unsung heroes whose goodness kept hope alive.

Themes

Survival Under Oppression

As the fascist grip tightens around Italy, survival becomes a daily calculation for Lili and those around her. This is not merely about physical endurance but also about negotiating the psychological and moral terrain of living under a regime that seeks to erase one’s identity.

Lili’s Jewishness marks her for exclusion, surveillance, and violence, and her strategies for survival become increasingly complex. She must conceal her affiliations, forge documents, escape cities, and endure starvation—all while preserving her sense of self and protecting Theo.

Her resistance to the regime is often quiet, expressed not through confrontation but through the preservation of dignity, memory, and life. Even the decision to flee or hide rather than confront the fascists head-on becomes a radical act of resistance when simply existing as a Jew is outlawed.

This theme explores how individuals survive not only through physical flight or evasion but also through acts of emotional resilience—through care, community, and memory. Every decision Lili makes is laced with danger and moral weight, yet her survival never drifts into moral compromise.

She refuses to become indifferent, even when such indifference could mean safety. In that refusal lies a profound form of defiance.

The theme shows how enduring under such brutal conditions demands not only bodily resourcefulness but also emotional and ethical clarity.

Friendship and Chosen Family

The bond between Lili and Esti lies at the emotional core of One Good Thing, surpassing the mere category of friendship to become something familial, expansive, and necessary. From their university days to their shared domestic life during the war, their relationship becomes a sanctuary amid a world unraveling.

Esti, bold and determined, complements Lili’s cautious but steady presence. The strength of their friendship is measured not just by mutual affection but by sacrifice, argument, forgiveness, and shared risk.

When Esti moves in with Lili during her most vulnerable moment—pregnant and alone—their household transforms into a stronghold of mutual care. Later, as they risk their lives to protect Jewish children and forge new identities for the persecuted, their friendship becomes the lifeline through which survival and resistance flow.

The relationship takes on the roles traditionally associated with family—co-parenting Theo, protecting one another, providing emotional ballast in a crumbling world. Their fights, particularly around the ethics of confrontation versus caution, further reveal how deeply invested they are in each other’s survival.

Even in absence, Esti’s influence continues to guide Lili, and her diary becomes a source of affirmation and strength. This theme asserts that in the face of collapsing institutions and familial separations, chosen family—relationships built on loyalty, love, and shared belief—becomes a foundation for emotional and ethical endurance.

Moral Courage and Ethical Risk

At multiple moments, characters are forced to choose between what is safe and what is right. Esti chooses to forge papers for strangers rather than retreat into anonymity.

Niko, despite his familial obligations and new fatherhood, joins Delasem’s covert operations. Lili, initially cautious and focused on self-preservation, finds herself teaching orphaned children, hiding fugitives, and eventually forging documents herself.

These actions are not born of impulsive bravery but of accumulated conviction. Moral courage here is quiet, slow-growing, and grounded in empathy and responsibility.

It is not romanticized as unerring heroism; instead, it is portrayed as a deeply conflicted and often painful reckoning with fear. The story presents moral courage as something that manifests in the most ordinary moments—deciding to stay in a town a few days longer, choosing to carry a child through a checkpoint rather than leaving him behind, deciding to trust a stranger.

This theme is also shaded by the cost of ethical risk. The losses are not just theoretical: people disappear, families are destroyed, futures are compromised.

Yet characters continue to act because to do otherwise would be a betrayal of their humanity. The novel asks what it means to be good in a time when goodness is outlawed, and it answers by portraying characters who, with trembling hands and breaking hearts, choose ethical action despite knowing it may destroy them.

Memory and Legacy

Throughout One Good Thing, memory is both a burden and a guide. Lili carries the weight of her mother’s memory, the haunting silence around Esti’s fate, and the unspoken legacy of Jewish persecution.

Memory here is not only a recollection of personal moments but a repository of cultural identity and moral imperative. It fuels her decision-making and gives shape to her longing for continuity and justice.

Massimo’s stories, the grief-laced silence after Auschwitz’s liberation, Esti’s diary entries, and even fleeting moments of shared joy all function as threads tying past to present. These recollections sustain Lili in moments of despair and act as a bridge between generations.

Theo, the youngest and most innocent, becomes both the inheritor and symbol of these memories. When he calls Lili “Mama,” it’s not just an emotional resolution but an acknowledgment of the legacy she has chosen to carry and pass on.

Esti’s diary also functions as a literal and symbolic embodiment of legacy—written memory that affirms Lili’s value, her sacrifices, and her worthiness to raise Theo. The novel presents memory not as a static archive but as a living force that shapes identity, fosters continuity, and provides moral clarity amid chaos.

In choosing to carry memory rather than discard it for convenience or escape, Lili enacts an active, conscious form of resistance to erasure.

Love as Resistance

Love, in its many forms—platonic, maternal, romantic—is portrayed as a subversive and sustaining force in the novel. At a time when dehumanization is law and fear seeks to isolate, every expression of affection becomes an act of defiance.

Lili’s maternal love for Theo, though unofficial at first, deepens into an unshakable bond that gives her the strength to endure life-threatening journeys, starvation, and moral uncertainty. This love is not idealized; it is messy, strained, and complicated by grief and guilt.

Yet it persists, offering both purpose and redemption. The rekindled romantic bond with Thomas, too, is portrayed not as a solution to trauma but as a fragile, hopeful connection built on mutual respect and emotional vulnerability.

It reminds Lili that she is still capable of joy, desire, and trust. Even her filial love for her father, complicated by his optimism and age, roots her in a sense of continuity and belonging.

Love here is never ornamental—it is what drives characters to risk, to hope, and to begin again. In a world where the powerful seek to dismantle families, erase identities, and suppress empathy, love becomes an active form of resistance.

It offers not escape, but the courage to build something new from the ruins. It is the one good thing that, even amid destruction, refuses to be extinguished.