One Small Mistake Summary, Characters and Themes

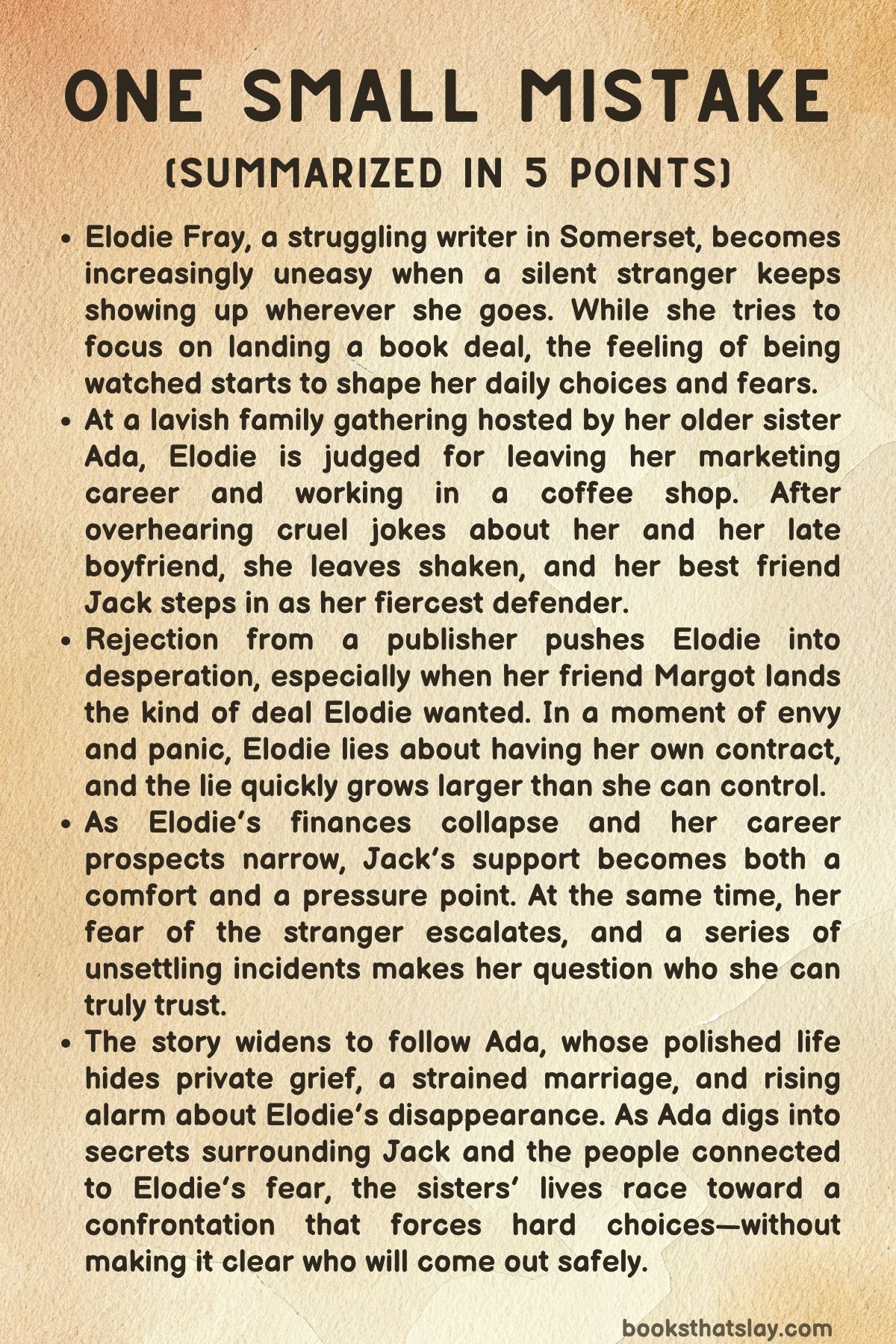

One Small Mistake by Dandy Smith is a psychological thriller set in modern Somerset and London, built around ambition, jealousy, and the risks of trusting the wrong person. Elodie Fray wants to be taken seriously as a writer, but rejection letters, money trouble, and family judgment keep closing in.

When she lies about landing a book deal, the lie spreads faster than she can control. At the same time, a man seems to be watching her, and the pressure of proving herself turns everyday choices into dangerous ones. The story follows how one false claim becomes the spark for a frightening chain of events.

Summary

Elodie Fray is a struggling writer in Somerset, working shifts in a coffee shop while trying to survive on dwindling savings. For days, she keeps noticing the same strange man in different places: outside the library, in the park, and near her workplace.

He doesn’t approach her, but his quiet staring and repeated appearances make her feel watched. Her coworker Hannah shrugs it off, and Elodie hesitates to involve the police because nothing “provable” has happened.

Still, the fear follows her home. She begins timing her routes, scanning crowds, and locking her door with shaking hands.

Elodie’s personal life offers little comfort. Her older sister, Ada, hosts a polished garden party in her grand home, surrounded by wealthy friends and the kind of stability Elodie’s parents admire.

Their mother Meredith uses the gathering to lecture Elodie about quitting her marketing career and “throwing away” her degree. Ada mostly ignores Elodie, and their cousin Ruby openly mocks her coffee-shop job.

Later, Elodie overhears Ada and Ruby gossiping about her in cruel detail, even twisting the death of Elodie’s boyfriend Noah into a joke. Noah didn’t die by suicide, as they imply, but in a hit-and-run, and the insult rips open grief Elodie still carries.

Elodie leaves in tears and runs into her best friend Jack Westwood, who has just arrived. Jack pulls her close, demands to know what happened, and becomes furious on her behalf.

He confronts Ada with cold sarcasm, then escorts Elodie away. Outside, he escalates the night from comfort to rebellion by stealing Ruby’s car keys and daring Elodie to take a joyride, repeating their old challenge: “How far will you go?” Angry and humiliated, Elodie gives in.

They race down country lanes, feeding off adrenaline and the sense that rules don’t apply to them.

A few days later Elodie goes to London to meet her literary agent, Lara. Elodie’s manuscript has reached a publisher through Lara, and Elodie has pinned everything on the outcome.

Lara delivers bad news: the editor admired Elodie’s writing but rejected the book for lacking a strong commercial hook, and the market now wants darker, real-life-leaning stories. Lara pushes Elodie to come up with grittier pitches quickly or risk losing representation.

Elodie leaves the meeting crushed, trying to pretend she can pivot on command.

That night she meets her closest friend, Margot, who is bubbling with excitement. Margot reveals she has signed a book deal with the very publisher that rejected Elodie, because she is co-authoring a memoir connected to her famous-model mother.

Elodie is stunned by the unfairness of it and sick with envy. When Margot asks how Elodie’s meeting went, Elodie lies on impulse and claims she has a deal too.

The lie works instantly: Margot squeals, celebrates, and begins planning public congratulations. Elodie smiles through it, already regretting what she has done.

Jack arrives the next morning with breakfast and a caretaker’s confidence, letting himself into Elodie’s space as if it’s natural. Elodie admits the truth to him: she was rejected.

Jack is furious at the industry and insists she is talented, but Elodie spirals into fear that her mother was right and she has destroyed her future. Jack pushes her to focus on writing and even encourages her to call in sick from her café shift to work on new pitches.

Elodie does, but then she’s seen running in the park on the day she claimed illness. Her manager fires her, and with rent looming, Elodie’s panic turns into desperation.

As the pressure rises, the “stalker” becomes more real. During a run, Elodie collides with the same man she has been seeing around town.

She bolts home, terrified, and finds a large bouquet on her doorstep with a sash congratulating her on her “book deal.” It’s from Margot, who believes Elodie’s lie. Elodie throws away the evidence and sends an expensive bouquet back to Margot to keep up appearances, digging herself deeper.

More rejections follow. Lara emails that Elodie’s new pitches have been turned down too, and even suggests that Elodie return to marketing.

At the same time, Ada pressures Elodie to attend a family dinner. Elodie arrives raw with humiliation, only to find the family has organized a surprise celebration for her “success.” Her father saw the congratulatory flowers at Elodie’s home and assumed they were real proof.

Elodie is trapped in front of everyone, forced to lie again while Ruby needles her about age, marriage, and children. Later that night, the man who followed her appears outside and confronts her.

Elodie falls and injures her wrist. Jack arrives and punches the man, driving him off, playing the hero at exactly the right moment.

Soon after, on the anniversary of Jack’s father Jeffrey’s death, Elodie visits Jack for their usual ritual. She accidentally walks in on him having sex with another woman.

He reacts with sharp anger and control, then smooths everything over at dinner by reinforcing the false book-deal story to Elodie’s family. Back at Elodie’s, a package arrives from Noah’s mother, Florence: Elodie’s manuscript has been returned with Noah’s margin notes, along with a letter asking Elodie to dedicate the future book to Noah.

The request, built on the same lie, makes Elodie feel trapped by her own invention. Jack promises he will “fix” everything.

Then the fear becomes physical. Alone at home with a broken lock, Elodie wakes to an intruder.

A cloth is forced over her mouth, she fights, breaks a mirror, and is drugged. She later wakes confined in a car in the woods, injured and nauseated, unable to escape because basic parts of the car have been tampered with.

After hours, Jack appears and “rescues” her, then admits the truth: he arranged the kidnapping with a friend. He claims it’s for her benefit.

True-crime sells, the world already believes she has a deal, and now she can “reappear” and write the kind of story publishers crave. He has plans, locations, and a ready-made narrative.

Elodie realizes that if she exposes him, she must also confess her lie, and Jack will face prison. Jack uses that leverage to force her into silence.

Elodie is taken to Wisteria Cottage, a coastal house tied to Jack’s childhood, and kept hidden while the public searches for her. Ada, meanwhile, suffers her own unraveling: her marriage to Ethan is cold and controlling, and she recognizes how much of her life has been built for appearances.

As the family’s fear grows, Ada begins to suspect Jack’s involvement. She visits Jack’s mother Kathryn under a false pretext and finds evidence linking Jack to the man who followed Elodie, including suspicious bank withdrawals that match payments.

Ada also discovers signs of old family secrets that suggest a deeper connection between their families, raising the possibility that Jack might be tied to them by blood.

Ada shares what she has with Christopher, a police officer, and pushes for action. Impatient with delays, she drives to Wisteria Cottage herself, spots proof that Elodie is inside, and searches until Elodie hears her voice.

The sisters reunite in terror and relief, but Jack returns unexpectedly. Elodie hides Ada and tries to manage Jack long enough for help to arrive.

Jack drags Elodie upstairs, restrains her, and prepares to assault her while insisting it is “love.” Ada attacks him, and the house turns into a fight for survival. In the chaos, Jack stabs Ada and the cottage catches fire.

Elodie, cornered and out of options, kills Jack and drags Ada outside as the flames take the house.

Two years later, Elodie and Ada have rebuilt their relationship and co-written a bestselling account of what happened, titled One Small Mistake. Elodie works with survivors and continues writing, choosing privacy and healing over public approval.

Ada reshapes her life as well, no longer willing to live for appearances. The story ends with the sisters still carrying scars, but finally free from Jack’s control and from the lie that began it all.

Characters

Elodie Fray

Elodie is the emotional center of One Small Mistake—a woman whose deepest vulnerability is not simply fear of being watched, but fear of being dismissed. She begins as a young writer living on dwindling savings and stubborn hope, trapped between the life her family insists is “sensible” and the life she chose because it felt necessary for survival.

Her sensitivity is not weakness; it is the lens through which she processes everything—rejection letters feel like judgments on her worth, and social slights land like proof that she is fundamentally “less than” her polished sister. That insecurity drives her most consequential mistake: lying about a book deal.

The lie doesn’t come from cruelty or vanity so much as a desperate reflex to protect herself from humiliation, especially when envy and shame collide in front of someone she loves. As her world tightens—job loss, agent pressure, family contempt—Elodie becomes easier to corner, and the story shows how coercion thrives when a person has already been trained to doubt their own instincts.

Her arc is ultimately about reclaiming truth: not only exposing Jack, but rebuilding a self that can survive being seen clearly. By the end, Elodie transforms trauma into agency on her own terms—writing again, helping other survivors, and choosing a softer kind of love that doesn’t demand self-erasure.

Jack Westwood

Jack is written as the most dangerous kind of antagonist: the one who first appears as a protector. He understands Elodie’s wounds with unnerving precision—her hunger for validation, her loneliness, her fear of becoming ordinary—and he uses that knowledge to position himself as the only person who truly “gets” her.

His loyalty at Ada’s party looks romantic and righteous, but it also establishes his pattern: he solves Elodie’s pain by escalating conflict and deciding, unilaterally, what justice looks like. As his control grows, his support becomes indistinguishable from management—he tells her what to do, when to rest, what to write, and eventually where she can live.

The cruelty of Jack isn’t only in the kidnapping and imprisonment; it’s in his ideology. He treats Elodie’s life as material, her body as leverage, and her consent as negotiable, rationalizing everything as love and “help.” The true-crime conversations are key to his psychology because he doesn’t merely enjoy darkness—he believes he can interpret it better than other people, and that belief becomes permission to act outside morality.

His history with violence and his father’s death hangs over him like a blueprint: unresolved rage, entitlement, and a need to control the narrative. Even his tenderness is weaponized—he offers closeness, then withholds freedom; he confesses, then frames confession as proof of intimacy.

Jack’s collapse is not sudden; it is a steady unveiling of a man who confuses possession with devotion and believes a story is worth more than a person.

Ada Fray Archer

Ada begins as Elodie’s polished opposite: the older sister who appears to have “won” life—beautiful home, wealthy husband, curated social world. But Ada’s character is built around the cost of that polish.

Her image is a form of armor, and the narrative gradually shows it is also a cage. She performs stability because she has been rewarded for it by parents, peers, and marriage, yet inside she is isolated, quietly grieving what she thought her life would be.

Her relationship to motherhood becomes the clearest symbol of that trap: she is pressured by culture to want children, pressured by her husband to delay them, and pressured by herself to meet expectations she’s no longer sure she believes. Ada’s growth is painful because it requires admitting she is unhappy in the life she defended—admitting that being admired is not the same as being loved.

Once Elodie disappears, Ada’s superficiality burns away and something sturdier emerges: courage, focus, and a protective ferocity that finally overrides the need to look perfect. Importantly, Ada’s redemption isn’t written as a sudden personality change; it is a release.

She stops protecting the family’s image and starts protecting her sister. In the end she becomes a woman who chooses her own future—leaving Ethan, building a career with meaning, and embracing a relationship where she is not an accessory but an equal.

Ruby

Ruby functions as both a person and a pressure system. She is cruel in a socially acceptable way—mocking Elodie’s job, policing her age and childlessness, turning status into entertainment—yet she does it with the casual confidence of someone who assumes the room will agree.

Her sharpness isn’t random; it’s a tool for dominance, a method of keeping herself centered in the hierarchy of who is successful and who is failing. What makes Ruby unsettling is that she rarely needs to raise her voice; she weaponizes insinuation, laughter, and “just joking” cruelty, and she benefits from Ada’s silence early on.

At the same time, Ruby’s baby shower environment also reveals her as someone deeply embedded in the culture of performance, where motherhood is social currency and women are evaluated relentlessly. Ruby’s character matters because she shows how social violence can feel normal—how humiliation can be served like small talk—and how that normalization leaves someone like Elodie primed to accept worse treatment later, because she has already been taught that her pain will be treated as an inconvenience.

Meredith Fray

Meredith represents the family’s moral and emotional weather—approval when you conform, disapproval when you deviate. Her criticism of Elodie is framed as concern, but it is concern shaped by reputation and fear of instability rather than empathy.

Meredith measures success by external markers: degrees used “properly,” respectable jobs, tidy narratives that can be repeated to others without embarrassment. That is why Elodie’s writing dream irritates her so intensely: it cannot be guaranteed, and it makes the family look uncertain.

Meredith’s attitude helps explain why Elodie lies so quickly about the book deal; she has been taught that love and pride are conditional. Yet Meredith is not portrayed as pure villainy—her collapse during the stress of Elodie’s disappearance hints at the costs of a life built on control.

Her motherhood is real, but it is filtered through anxiety and social rules, and the story implies that her harshness is partly inherited, partly chosen, and ultimately harmful even to herself.

Ethan Archer

Ethan embodies quiet, institutional control—the kind that doesn’t need shouting because it is backed by money, status, and the assumption that his needs come first. His response to Ada’s possible pregnancy, and the broader tone of their marriage, reveals a man who treats Ada’s body and future as scheduling problems.

He is not written as a melodramatic monster; he is worse in a familiar way: self-interested, dismissive, and confident that Ada will adapt. His emotional absence contributes to Ada’s loneliness and makes her more vulnerable to living for appearances, because appearances are the only affection she reliably receives.

When he leaves and the separation becomes real, Ethan’s role is clarified: he was never Ada’s partner, only the person whose life she was expected to fit inside.

Margot

Margot is Elodie’s mirror in a different direction: warmth, momentum, and a kind of effortless social luck that Elodie both loves and resents. She is not malicious; her excitement about her own book deal is genuine, and her concern about the stalker is sincere.

But Margot’s presence intensifies Elodie’s insecurity because Margot represents what Elodie wants most—recognition—and gets it through a connection that is not purely earned in the way Elodie needs hers to be. That contrast is precisely why Elodie lies to her.

Margot becomes the accidental trigger for the plot’s most catastrophic escalation: her bouquet and celebration spread the lie into the wider family, turning Elodie’s private shame into public expectation. Margot’s role is important because she shows how envy can exist inside love, and how a good friend can still become a catalyst for disaster without doing anything wrong.

Lara

Lara, the literary agent, embodies the cold logic of the marketplace and the psychological violence of “professional realism.” She is not cruel for sport; she is pragmatic, focused on trends, hooks, and what sells, but that pragmatism lands on Elodie like condemnation because Elodie’s writing is personal. Lara’s push for darker, “real-life-inspired” stories is thematically loaded: it becomes one of the forces that nudges Elodie toward Jack’s trap, because it reinforces the idea that pain is currency.

Lara also represents conditional support—encouragement as long as there is potential profit—mirroring the conditional approval Elodie receives from her mother. Even when Lara is simply doing her job, she serves as a reminder that Elodie’s dream is judged by systems that do not care how much of herself she has poured into it.

Noah

Noah is present as memory, but his influence shapes Elodie’s core motivations. He represents the gentlest form of belief: the person who encouraged her writing not as a strategy, but as a truth about who she is.

His margin notes on her manuscript make him feel intimate and ongoing—like a voice that still speaks to her when everything else becomes hostile. The cruelty of Ruby’s joke about his death, and the later request from Noah’s mother to dedicate the book, reveal how grief can be exploited by others and how Elodie’s private loss becomes part of public narrative again and again.

Noah’s role also highlights the difference between supportive love and Jack’s consuming love; Noah inspires Elodie toward freedom, while Jack claims to love her by taking freedom away.

Florence

Florence, Noah’s mother, functions as a conduit between Elodie’s past and the lie she is now trapped inside. Her letter and the returned manuscript with Noah’s notes are not just sentimental; they tighten the emotional noose around Elodie by making the fake book deal feel morally irreversible.

Florence’s request for a dedication turns Elodie’s private guilt into something sacred and public, increasing the pressure to keep performing success. She is written as kind and earnest, which is exactly why her involvement hurts more—Elodie cannot dismiss her as toxic; she must face that her deception is now affecting someone who has already lost a son.

Jeffrey Westwood

Jeffrey’s presence is a haunting origin point for Jack’s darkness. He is remembered as violent and abusive, and the trauma Jack carries from that household explains why Elodie understands him so instinctively and why she has long viewed him as someone to protect.

But Jeffrey’s journals also complicate the story by suggesting a history of fear around Jack’s nature—an implication that Jack’s violence was not only learned but also emerging early, noticed, named, and possibly hidden. Jeffrey’s death, framed as suicide yet surrounded by suspicion, becomes the mythic event that defines Jack’s capacity for manipulation: the possibility that Jack can create a convincing narrative around a corpse.

Whether Jeffrey was monster, victim, or both, his legacy is the blueprint of damage that Jack later perfects into control.

Kathryn Westwood

Kathryn is a figure of secrecy and denial. She appears as a mother still tethered to her son’s needs, even when those needs are sinister, and the detail that she is shredding documents for Jack suggests a willingness to protect him that crosses ethical boundaries.

Her connection to the Fray family through past affair implications adds another layer: Kathryn is not only Jack’s mother but part of the tangled web of hidden histories that destabilize the sisters’ sense of reality. She is dangerous not through direct violence but through complicity—the kind that quietly clears the path for harm to continue.

Christopher

Christopher represents grounded competence in a story full of manipulation and performance. He listens, he advises caution, and he tries to use the system—warrants, evidence, procedure—rather than emotion.

That restraint can frustrate Ada, but it also makes him feel like the opposite of Jack: someone who does not confuse urgency with entitlement. His near-romantic tension with Ada matters because it shows Ada learning a healthier dynamic, one built on respect rather than status.

Christopher’s role ultimately supports Ada’s transformation into action; he doesn’t save her, but he helps her turn fear into strategy.

Hannah

Hannah’s dismissiveness early on is small but meaningful. She represents the social reflex to minimize women’s fear—especially fear that has not yet become “provable.” Her reaction contributes to Elodie’s isolation and self-doubt, reinforcing the idea that Elodie might be overreacting.

Even though Hannah is not central later, her role echoes one of the book’s recurring themes: danger often escalates in the space between intuition and evidence, and the people around you can unintentionally widen that space by insisting you stay calm.

Richard

Richard embodies institutional indifference and petty power. He fires Elodie for calling in sick, refusing to see the larger context of her fear and instability, and later he capitalizes on her disappearance by selling defamatory stories.

He is not a mastermind, but he is part of the ecosystem that feeds on women’s vulnerability—punishing them for trying to cope, then profiting when they fall apart. His presence shows how easily a person’s crisis can become someone else’s opportunity.

Arabella

Arabella represents the closed door of the “practical” life Elodie left behind. Elodie reaches out in desperation, hoping the old world might still catch her, and Arabella’s refusal is not framed as personal betrayal so much as brutal reality.

That rejection matters because it eliminates the comforting fantasy that Elodie can retreat to stability whenever she wants. It heightens her dependence on Jack at exactly the wrong moment, and it intensifies the story’s sense that Elodie is being herded toward a single path.

George

George is a small but humane presence—a reminder that kindness exists without strings. His decency stands out precisely because so many other interactions are transactional, judgmental, or performative.

George doesn’t fix anything, but he offers Elodie something rare in her life at that point: uncomplicated respect. In a narrative about manipulation, such ordinary kindness becomes quietly radical.

David Taylor

David is the mechanical arm of Jack’s plan, the man Elodie misreads as a random stalker when he is actually paid and positioned. His character shows how easily fear can be engineered and how a predator can outsource the early stages of terror to create confusion and self-doubt.

David’s function is less psychological complexity and more thematic clarity: the “serial-killer glasses” figure is proof that Elodie’s instincts were right about being followed, even though she was wrong about why. That twist sharpens the book’s central horror—sometimes the threat is not a stranger at all, but the person standing closest, directing the stranger like a prop.

Themes

Fear, Surveillance, and the Everyday Loss of Safety

Elodie’s sense of being watched begins in ordinary places—outside a library, on a park path, in the coffee shop where she works—and that familiarity is what makes it so destabilizing. The story shows how fear does not require an overt attack to become real; it grows from repetition, from being observed without consent, and from the constant calculation of risk that gradually takes over a person’s mind.

Elodie keeps trying to argue herself out of her own instincts because the stranger “hasn’t technically done anything,” and that gap between legal certainty and lived safety becomes a pressure point. Her hesitation to tell Jack, her attempts to normalize what she’s experiencing, and her choice to avoid the police reflect how easily someone can be pushed into silence when the threat is still “deniable.” The dread is not only about the stranger’s presence but also about the way that presence begins to dictate Elodie’s choices—how she walks home, how she judges strangers, how she evaluates her own reactions.

Even when others encourage her to act, she is already trained by social expectations to minimize, to avoid appearing dramatic, and to accept discomfort as the price of moving through public life. The theme becomes even harsher once the truth is revealed: the surveillance and stalking were not random; they were structured, funded, and used as part of a plan.

That shift reframes the earlier fear as something engineered, turning Elodie’s daily reality into a controlled environment. By the time she is isolated at Wisteria with no phone or TV, “safety” becomes a word Jack uses to justify captivity, showing how the language of protection can be weaponized.

The story keeps returning to one central violation: the removal of choice. Whether it is the silent man in town or Jack’s locked doors later, the feeling is the same—someone else has decided Elodie’s freedom is negotiable.

Ambition, Creative Identity, and the Cruelty of Gatekeeping

Elodie’s writing is not presented as a hobby or a casual dream; it is tied to her sense of self, her past, and her need for a life that feels truthful. When she describes rejection as personal rejection, it lands because her work is “made of her life and voice,” so dismissing it feels like dismissing her.

The publishing world she faces demands a “hook,” favors “darker” real-life material, and treats market fashion as more important than craft or emotional honesty. That pressure forces Elodie into a narrowing corner: she must either shape herself into what sells or accept being pushed out.

The theme becomes sharper through the contrast with Margot’s deal, which is not earned through years of solitary work but delivered through proximity to fame—her mother’s model memoir, the built-in platform, the publisher’s appetite for a recognizable story. Elodie’s jealousy is messy and human, and it shows how unequal systems don’t just block people; they also distort friendships and self-respect.

Her lie about getting a deal is not simply vanity—it is a survival reaction to humiliation, especially after being judged by her family and dismissed by an industry that keeps moving the goalposts. Later, the plot exposes the ugliest version of that gatekeeping: Jack treats trauma as a commodity and suggests that abducted women get book deals because they have the “right ticket.” That idea is horrifying because it has a recognizable logic in the real world of attention economics, where suffering can become currency.

In One Small Mistake, the path to success is shown as morally compromised long before the kidnapping occurs, which makes the eventual exploitation feel like the extreme endpoint of a culture that rewards confession, scandal, and pain. By the time Elodie and Ada publish their bestselling book after surviving violence, the theme refuses to deliver a simple victory narrative.

The success exists alongside rage, grief, and public suspicion, including a reporter framing Elodie as someone who “profited.” The story insists that creative achievement does not erase the brutality that produced the material, and it questions the audience’s hunger for “inspired by real events” when real people have to live with the consequences.

Family Hierarchies, Shame, and the Hunger for Approval

Elodie’s family environment runs on comparison and performance. Ada is the polished success story with the grand house and wealthy husband; Elodie is treated as the disappointment who “wasted” her degree and chose instability.

The parents’ approval operates like a scarce resource, and Elodie is made to feel she must earn basic respect through conventional milestones: a stable career, the right kind of partner, the right kind of life. Meredith’s lectures and Ruby’s mockery show how shame can be delivered as “concern” or “humor,” allowing cruelty to hide behind social manners.

Ada’s silence at the garden party, especially when Ruby humiliates Elodie, is its own kind of betrayal. The theme deepens because the sisters’ conflict isn’t only personal; it is structural.

They have been assigned roles: Ada as the family’s proof of success, Elodie as the cautionary tale. That division shapes how Elodie responds to humiliation—she runs, she drinks, she acts recklessly with Jack—because she has no safe place to put her anger.

At the same time, Ada’s later chapters reveal that her “perfect” life is a controlled display hiding loneliness, reproductive pressure, and a marriage built on Ethan’s preferences. Her private grief about pregnancy and the way motherhood becomes a public test at Ruby’s baby shower show how women are boxed in by expectations that are presented as natural and unavoidable.

Ada’s bond with Jennifer is important because it offers an alternative model: a woman who is childless by choice, confident, and not apologizing. That model cracks the spell of Ada’s socially curated existence and makes it possible for her to admit she wants freedom.

The story ultimately reframes the sisters’ relationship from rivalry to recognition. When Ada starts investigating Elodie’s disappearance, she stops being the “good daughter” maintaining appearances and becomes a protector willing to risk social fallout.

Their reunion is powered by honesty that arrives too late to prevent harm but not too late to rebuild connection. The later closeness between them, including co-writing their book and defending each other in public, becomes an answer to the family’s old hierarchy.

Approval still matters—parents’ pride still lands emotionally—but the sisters learn to anchor themselves in mutual loyalty rather than in the shifting judgments of relatives who once used them as status symbols.

Friendship, Dependency, and the Danger of Being “Saved”

Jack begins as the person who shows up with breakfast, cleans Elodie’s room, tells her she is talented, and stands between her and the humiliations her family inflicts. He also holds a longstanding bond with Elodie built on childhood daring and a shared language of risk, captured in the phrase “How far will you go?” That history makes his presence feel inevitable and protective, which is exactly what makes the theme so unsettling.

The story shows how devotion can slide into ownership when one person frames themselves as the only one who truly understands what the other needs. Jack repeatedly decides things “for” Elodie: urging her to call in sick, pushing her toward grittier pitches, insisting she not tell the truth at the surprise party, managing narratives, staging solutions.

Even before the kidnapping, his confidence in his right to steer her life is presented as love. The imbalance grows because Elodie is vulnerable—financially unstable, professionally rejected, ashamed, frightened by a stalker—and Jack positions himself as the antidote to all of it.

That is how dependency forms: not through one dramatic decision, but through many small moments where autonomy is traded for relief. Once Jack reveals the kidnapping plan, the theme becomes explicit: he is not rescuing her; he is authoring her.

He builds an alibi, maps a plot, predicts public response, and expects Elodie to perform the role he has written because it will “help” her career. His logic is chilling because it mimics a distorted version of support—he claims he is creating a path to happiness.

The captivity at Wisteria turns this into a full system: isolation, information control, emotional punishment, and forced intimacy. The night when their relationship becomes sexual underscores the theme’s complexity because it blurs desire with coercive context; affection does not cancel danger when the power balance is broken.

After the assault, Jack’s insistence that it is “proof of love” shows the final collapse of boundaries between care and harm. One Small Mistake uses Jack to expose a frightening truth about certain relationships: the most dangerous person may be the one who knows your fears, your dreams, and the exact words that make control sound like devotion.

Gendered Expectations, Motherhood Pressure, and Social Policing

The story places women under a constant microscope, not just through literal surveillance but through social evaluation. Elodie is judged for her job, her ambition, her financial instability, and her lack of conventional milestones.

Ada is judged for her marriage performance, her hosting, her appearance, and especially her childlessness, which becomes public property in conversations at Ruby’s baby shower and in the gossip Ada later explodes at during the charity bake sale. These pressures are not presented as isolated rude comments; they function like a disciplinary system that pushes women to self-censor and self-correct.

Ada’s memory of Ethan’s response to a possible pregnancy—treating it as inconvenient and controllable—shows how even reproduction can become something negotiated by male comfort and timing. Her decision to secretly remain on birth control reveals a quiet rebellion: she is protecting herself from being pulled deeper into a life she does not want, while still trapped in a marriage where honesty feels unsafe.

Jennifer’s presence matters because it offers a credible alternative: a woman who has been punished for caretaking (raising stepdaughters, then being abandoned) yet chooses a future based on her own desires rather than on social approval. The theme also connects to the publishing plotline, where the market preference for “darker, real-life-inspired stories” echoes a cultural appetite for women’s suffering as entertainment.

Elodie’s eventual public scrutiny at the signing—being accused of profiting from Jack’s death—shows how women are judged no matter what they do. If they stay silent, they are questioned; if they speak, they are blamed for making it public; if they succeed afterward, they are accused of exploiting their own survival.

The book also highlights how women can become enforcers of these expectations, as Ruby mocks Elodie’s work and age, and as Meredith pressures Elodie toward stability, even if she believes she is acting lovingly. At the end, Ada defending Elodie publicly becomes a form of resistance: refusing to let a survivor be reduced to a morality play for onlookers.

The theme lands as a critique of a world where women’s lives are treated as communal property—open for commentary, pity, suspicion, and consumption—while women themselves are expected to remain gracious, quiet, and grateful.

Trauma, Memory, and the Fight to Reclaim a Future

Loss and trauma shape nearly every major decision in the story, but they don’t appear as neat lessons; they appear as triggers, spirals, and sudden collapses. Elodie’s grief for Noah is ongoing and complicated by the way others weaponize his death against her, especially the cruel joke that he “killed himself to escape her.” That moment doesn’t just hurt; it contaminates memory, making even love feel vulnerable to public distortion.

The manuscript returned with Noah’s margin notes becomes another kind of haunting: proof that someone once believed in her, arriving at the worst moment, sharpening both guilt and longing. Jack’s trauma history is also central: the violent father, the discovery of Jeffrey’s body, and the ambiguous circumstances around that death.

The story suggests that trauma without accountability can become a justification for harm, especially when someone learns to treat pain as permission rather than as something to heal. Elodie’s captivity, assault, and imprisonment intensify the theme by showing trauma as an experience that breaks time—days blur at Wisteria, information is withheld, fear becomes routine, and the body becomes a battleground.

The aftermath two years later refuses to present closure as simple. Elodie volunteers at a rape crisis center, indicating a desire to turn suffering into support for others, but she also chooses anonymity by writing under the name “Noah Pine,” which suggests both tribute and the need to protect her identity from public consumption.

The co-authored bestseller shows recovery as complicated: telling the story can be empowering, but it can also keep the wounds visible to strangers who feel entitled to an opinion. Even peace is described as something Elodie has to accept, not something that arrives naturally.

The final view of “gentler love” contrasts with the earlier relationships shaped by risk, secrecy, and performance. It suggests that reclaiming a future is not about forgetting what happened; it is about refusing to let violence define the limits of what love and life can become.