Only Stars Know the Meaning of Space Summary, Characters and Themes

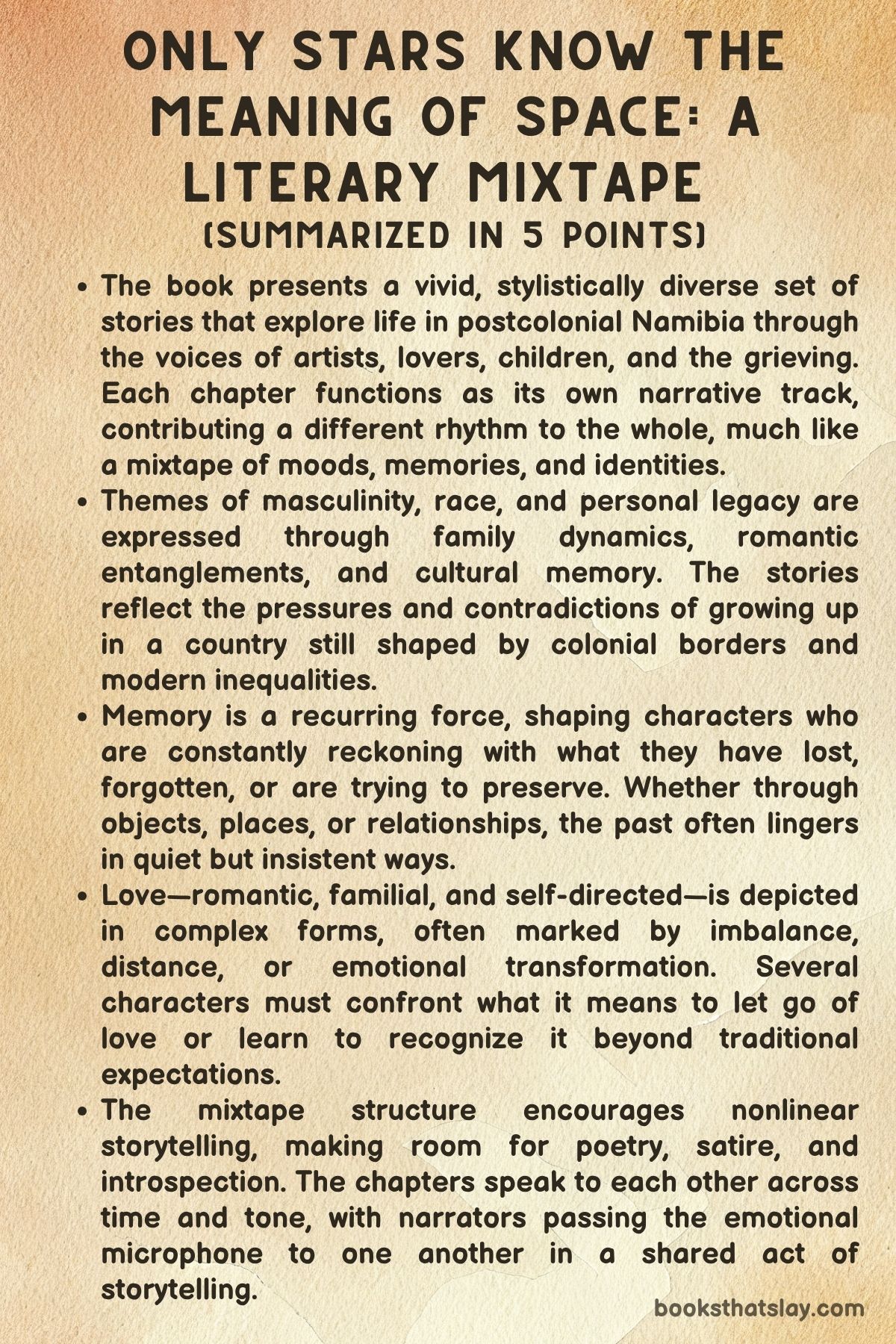

Only Stars Know the Meaning of Space: A Literary Mixtape by Rémy Ngamije is a collection of short stories styled as a mixtape.

Each chapter plays like a track, building emotional resonance rather than advancing a single narrative. Set primarily in Namibia, the stories reflect on masculinity, love, grief, art, and memory.

Tied together through motifs of music, movement, and memory, the mixtape allows the reader to feel more than follow. It explores the private lives of individuals against the pressures of postcolonial legacy and cultural change.

Summary

Only Stars Know the Meaning of Space begins with “The Hope, The Prayer, and The Anthem,” where a narrator reflects on turning thirty. He measures youthful dreams against the compromised landscape of adult reality.

The tone is quiet and introspective, grappling with disappointment, growth, and missed ambitions. In “Crunchy Green Apples,” a former lover’s memory lingers in household routines like doing laundry and cooking, making the narrator’s healing process incomplete.

“Black, Colored, and Blue” traces an affair between the narrator and a gangster’s girlfriend. It’s not just about desire, but about powerlessness and guilt amid social silence and gendered violence.

“Little Brother” centers on a late-night phone call. The strained bond between two brothers is shaped by rivalry, resentment, and unspoken affection.

In “Tornado,” the narrator races through a hospital to find his mother. The fragmented narration mimics the chaos and fear of grief.

“The Sage of the Six Paths” recalls five friends who build their own mythologies using anime and video games. Their escapism reflects economic disparity and racial boundaries.

“From the Lost City of Hurtantis to the Streets of Hellodorado” tells the story of Franco, navigating heartbreak and trauma while moving through the city’s physical and emotional labyrinths.

“Nine Months Since Forever” captures emotional stasis. Grief has taken root but cannot grow or break apart.

“Hope is for the Unprepared” delivers a confession of self-deception. The narrator admits to overestimating his emotional strength in love and life.

“Sofa, So Good, Sort Of” blends migration, social mobility, and family. The story is told through memories centered on a tattered ottoman and references to artist John Muafangejo.

The B-side begins with “Wicked,” in which a woman reclaims herself after heartbreak. Her autonomy is raw, imperfect, but honest.

“The Neighborhood Watch” explores a group of boys who scavenge trash in rich neighborhoods. Through their eyes, the wealth divide in Namibia becomes sharp, but not humorless.

“Important Terminology for Military-Age Males” functions as a glossary of masculinity. The chapter critiques surveillance, trauma, and the dangers of being a young Black man in a postcolonial world.

In “Annus Horribilis,” one man’s life unravels emotionally and economically. The story conveys the quiet collapse of someone trying to hold it together.

“Love is a Neglected Thing” compares biblical teachings on love with a modern relationship’s disappointments. It’s about how spiritual ideals rarely match emotional reality.

In “The Giver of Nicknames,” schoolyard politics reveal racial hierarchy and violence. The privileged commit harm without consequence, while nicknames become instruments of social control.

“The Other Guy” looks at a woman’s realization that her poet-lover is more myth than man. She chooses peace over the ache of half-fulfilled love.

“Seven Silences of the Heart” portrays a funeral through color, sound, and stillness. The story studies how ceremony masks grief while also honoring it.

“Granddaughter of the Octopus” features a grandmother who recounts her five loves. She offers candid lessons on womanhood, survival, and storytelling.

In “Only Stars Know the Meaning of Space,” a woman remembers a romance that was more spiritual than possessive. She accepts the poet for what he is—changing, uncontainable.

“End Credits” follows a narrator who forgives a partner despite his friends’ protests. Forgiveness is framed as rebellion against societal norms of anger and revenge.

“The Poet and the Pineapple” traces a love that shifts from passion to disillusionment. Even grocery shopping reveals tensions between romantic ideals and everyday reality.

“Cartography of Love” maps the narrator’s travels across countries and flings. Each stop is a failed attempt to recover a former love.

“Future of Grief” brings grief to life as a voice and a guide. The narrator is told he will survive it, but only through acceptance and time.

The book closes with “Thump-Thump,” where the narrator imagines becoming a star. Distant but luminous, he accepts solitude and radiance as coexisting truths.

Characters

The Poet (Narrator/Protagonist Figure)

The most recurring and cohesive voice in the collection, the Poet serves as both observer and participant in the stories. He is introspective, flawed, and eternally searching—for meaning, for peace, for identity.

His voice is that of a postcolonial intellectual deeply wounded by generational trauma, romantic disappointment, and the societal contradictions of modern Namibia. In many narratives, he is aging and disillusioned, coming to terms with broken dreams and unreciprocated love.

He tries to reconcile the tenderness of boyhood with the hardness of adult masculinity. In relationships, he often appears as the one left behind, a figure others use as a temporary harbor before sailing on.

Still, he does not resent this entirely. Instead, he holds space for it, philosophically, and often with a heart that refuses to harden.

Through this central figure, the book investigates vulnerability in Black men. It challenges stereotypes of stoicism and dominance with meditations on softness, artistry, and emotional depth.

The Woman Who Leaves (Poet’s Lover)

She is never named consistently, often known only through her relationships with the poet or abstract titles like “the other girl” or “the woman who called him a poet.” She is complex—simultaneously nurturing, free, wounded, and unforgiving.

She often represents both love and its end, beauty and its fleetingness. Through her voice, especially in stories like The Other Guy and Only Stars Know the Meaning of Space, we learn that she is not a victim of abandonment but an agent of self-liberation.

She departs relationships with clarity and intention, understanding her needs and acknowledging the poet’s inability to fulfill them. Her stories speak to female autonomy in the face of male idealism.

They offer an alternative lens to romantic suffering: one rooted in empowerment rather than martyrdom. Her departure is not escape but self-restoration.

Franco

Franco appears in mythic terms, most notably in From the Lost City of Hurtantis to the Streets of Hellodorado. He is a symbol of youthful rebellion, heartbreak, and broken promises.

Caught between being a friend, a rival, and a tragic hero, Franco embodies the cost of not conforming—whether in sexuality, ambition, or cultural identity. His narrative is textured by magic realism, adding a dreamlike sheen to his descent.

Franco represents the parts of ourselves we mythologize to survive the harshness of real memory. His fall is not entirely tragic.

There is a quiet dignity in his refusal to follow the prescribed script of success or masculinity. He is a relic of what cannot be domesticated.

The Little Brother

In Little Brother (Or, Three in the Morning), the younger sibling emerges as both antagonist and mirror. He is irresponsible, brash, and constantly in trouble.

Yet his vulnerability and dependence expose the elder brother’s buried tenderness. The younger brother triggers unresolved trauma, envy, and familial duty in the narrator.

Their relationship encapsulates a broader tension within Black families navigating intergenerational pain. Though he appears only briefly, he symbolizes a recurring theme in the book.

This theme is the difficult love between men in spaces that offer them few safe emotional outlets. He is a test of love disguised as nuisance.

The Matriarch / Grandmother

The grandmother in Granddaughter of the Octopus commands the page with her wisdom, humor, and irreverent attitude toward patriarchal tradition. Having loved and left multiple men, she tells her granddaughter not to suffer fools or sentimentality.

Her character breaks the stereotype of the demure, saintly elder woman. She replaces it with a matriarch who is unapologetically herself.

She understands the world not through ideological purity but through lived experience. Her survival is a pedagogy.

Her narratives of romance are as much about independence as they are about intimacy. She is a beacon of female resistance in a deeply male-centric narrative world.

Donnie Blanco

Donnie Blanco, the privileged white classmate in The Giver of Nicknames, is a chilling figure of structural power and racial violence. His actions, particularly the sexual assault he commits, become a lens through which the narrator critiques whiteness, legacy, and the toxic shield of colonial privilege.

Donnie is not just a singular villain but a representation of how violence is protected, rationalized, and passed down through social systems. His nickname, like others in the story, becomes a marker of betrayal rather than camaraderie.

He is the dark counterpart to the Poet. He is a man who uses language to mask harm rather than reveal truth.

John Muafangejo (Symbolic Presence)

Though not a character in the literal sense, John Muafangejo’s spirit infuses the narrative with a quiet authority. In Sofa, So Good, Sort Of, Muafangejo’s linocuts become touchstones for memory, resilience, and artistic lineage.

He stands as a creative ancestor to the narrator. He reminds him of the power of art to witness suffering and still endure.

Through him, the narrative links the domestic with the historical. It also connects the aesthetic with the emotional, making him a spiritual character in the mixtape’s fabric.

Cicero

Cicero, the reflective protagonist in Nine Months Since Forever, is less a defined individual and more a vessel for suspended emotion. His name evokes Roman intellect and endurance, yet in this narrative, he is paralyzed by grief and time.

He doesn’t seek closure. Rather, he inhabits the space between past and present.

Through Cicero, the book investigates what it means to dwell in emotional purgatory. It shows a state where forgetting is impossible and healing is a distant ambition.

The Woman Traveler (Narrator of Cartography of Love)

She is the globe-trotting seeker in Cartography of Love, using physical distance as a strategy for emotional healing. Her story captures a familiar post-breakup pattern—trying to replace intimacy with experiences, lovers with landscapes.

Even as she collects memories from Ghana, Mozambique, and Thailand, she learns that grief cannot be walked away from. Her character is deeply vulnerable, haunted by longing, but also brave in her pursuit of herself.

She resists being reduced to her heartbreak by insisting on transformation. Even if the journey is imperfect and incomplete, she chooses motion over stagnation.

The Child Survivors / Street Boys

In The Neighborhood Watch, the unnamed group of boys navigating Windhoek’s trash bins offer a haunting yet playful vision of life on society’s margins. They are scavengers, hustlers, and dreamers, caught between survival and invisibility.

Their bond is fierce, often expressed through banter and mischief. But underneath lies deep sorrow.

These characters are lenses into class disparity, institutional neglect, and racialized poverty. Yet they are also vessels of resilience and joy.

Their humor is sharp, their loyalty palpable, and their perspective unfiltered. They ground the mixtape in gritty urban realism.

Themes

Identity and Self-Perception

The theme of identity is present throughout the book, articulated through fragmented lives navigating love, trauma, and cultural displacement. The narrators—some recurring, others singular—expose the tensions between the versions of themselves they perform and the ones they privately endure.

In chapters like “Hope is for the Unprepared” and “The Other Guy,” characters examine the dissonance between who they are and who they hoped to be. This contrast often plays out under the gaze of others who cannot or choose not to understand them.

Masculinity is especially complicated here. Being a Black man in postcolonial Namibia demands performance, yet that performance often silences vulnerability.

This duality appears in the form of “the poet” and “the man,” and also in the lexicon-heavy structure of “Important Terminology for Military-Age Males,” which uses definitions to frame the rigid expectations imposed on young men.

Elsewhere, identity is tied to memory. “Black, Colored, and Blue” juxtaposes personal guilt with inherited colonial trauma, making it impossible for the narrator to exist without historical context.

The self becomes layered, performative, and sometimes unrecognizable. Even in “Crunchy Green Apples,” heartbreak is less about loss and more about the narrator’s inability to let go of the person he was when he was loved.

The mixtape format reinforces this theme. Like a cassette tape with two sides, the characters often contain contradictions, operating between what they used to be and what they are becoming.

This dynamic examination of identity resists fixed definitions. It suggests instead that identity is as much about fragmentation and contradiction as it is about cohesion.

Love and Its Discontents

Love in this book is rarely idyllic. It is bruised, unbalanced, and ephemeral.

It emerges not as a singular event but as a spectrum of emotions—longing, loss, infatuation, intimacy, betrayal, and, sometimes, peace. Across chapters like “Love Is a Neglected Thing,” “Only Stars Know the Meaning of Space,” and “Cartography of Love,” relationships are marked by incompleteness.

Lovers part ways not always because of lack of love but because of an inability to become what the other needs. Love becomes something experienced through aftershocks, in fragments and echoes.

In these stories, women often reclaim their agency after emotionally exhausting relationships. They decide to leave men who are emotionally distant or burdened by past trauma.

Men, in contrast, often realize their need for love too late. They only recognize its shape through its absence.

The recurring poetic male figure is simultaneously adored and resented. He cannot be pinned down and thus cannot provide the stability his lovers seek.

Stories like “The Poet and the Pineapple” dramatize how even the mundane aspects of life—like grocery shopping—become saturated with emotional tension when love is uncertain.

Love is also transnational in “Cartography of Love,” where the narrator seeks healing across continents. Geography, however, cannot fix the emotional void within.

Ultimately, love is shown as something both transformative and devastating. It becomes a space of vulnerability where people try and often fail to truly connect.

The characters seem to ask: is love something we build, something we receive, or something we survive?

Grief and the Passage of Time

Grief is a constant undercurrent in this mixtape of stories. It takes many forms—grieving people, lost possibilities, failed relationships, broken dreams, and even lost versions of the self.

In chapters like “Tornado,” “Seven Silences of the Heart,” and “Future of Grief,” the narratives dwell on the physicality of loss. Characters don’t just think about what’s missing—they feel it in their bodies, in their rituals, in how they move through rooms or watch time pass.

Grief is personified, spiritualized, and sometimes silenced, depending on the speaker. The tone varies—some characters fight against grief, others surrender to it.

In “Future of Grief,” grief becomes a companion, a being to converse with. Pain isn’t something one escapes but something one learns to live with.

“Seven Silences of the Heart” connects grief to cultural ceremony. Funerals and rituals try to organize pain into something manageable, even if they fail.

The stories suggest that time doesn’t necessarily heal. It only changes the form grief takes.

Past events linger like static on a cassette; they remain embedded, never quite fading. This is echoed in how stories like “Nine Months Since Forever” present grief as suspension, as a kind of frozen time.

Grief is not just about death. It is about emotional stagnation, about waiting for something that will never return.

Yet, even in sorrow, there is often a quiet hope. There is an acknowledgment that continuing, even in pain, is a radical act of survival.

Postcolonialism and Socioeconomic Inequality

Namibia’s colonial legacy and the economic disparities it left behind form a powerful backdrop for many of the stories. The characters live with inherited traumas—racial stratification, cultural dislocation, and class-based humiliation—that they cannot escape.

In “The Neighborhood Watch” and “The Giver of Nicknames,” class divides are portrayed as physically observable, often brutal realities. Children forage in trash from affluent neighborhoods, white privilege protects abusers, and nicknames become weapons and survival mechanisms in oppressive school environments.

These stories lay bare the structural inequalities that persist long after colonialism’s official end. Yet, this critique is never just academic—it is grounded in the everyday lives of characters who suffer from and participate in these systems.

The narrator in “Black, Colored, and Blue” engages in a dangerous relationship not just because of personal desire. He does so because of the silence demanded by historical power dynamics.

The legacy of apartheid-era categorizations—Black, colored, white—haunt the narratives. They affect how people love, work, and even see themselves.

Artistic references, such as to John Muafangejo, are used not only as cultural touchstones but as symbols of resistance and identity reclamation. The social commentary is sharp but layered.

There are no easy villains or heroes. Even those who benefit from inequality are portrayed with psychological nuance.

What emerges is a landscape where inequality is not just a condition. It is a force shaping every decision, every heartbreak, every moment of self-doubt.

Art, Storytelling, and the Power of Memory

The mixtape format of the book is not just structural. It reflects a deeper meditation on the power of art and storytelling as tools for survival, remembrance, and resistance.

Each chapter operates like a track, with its own rhythm, theme, and voice. This emphasizes that memory and meaning are constructed through narrative fragments.

This is most explicit in stories like “Sofa, So Good, Sort Of” and “Only Stars Know the Meaning of Space,” where characters look back on artistic influences and emotional milestones through specific objects, songs, or images. Art becomes a way to process the past.

Muafangejo’s linocuts, mixtapes, poems, even the physical arrangement of furniture are loaded with emotional and cultural significance. Storytelling allows characters to reframe trauma.

They make sense of events that were once chaotic or overwhelming. The narrators are aware they are constructing memory.

They pause, rewind, fast-forward, and sometimes erase. This reflective mode gives the reader not only a sense of what happened but also of how and why it’s remembered.

The structure itself critiques linear storytelling. It suggests that lives, especially those shaped by love, pain, and colonial legacies, cannot be flattened into chronology.

Instead, they must be listened to like music. Sometimes out of order, sometimes off-key, but always bearing meaning.

In this way, the mixtape becomes both a personal and collective archive. It is a testimony to lives lived in the margins and voices echoing long after the music ends.