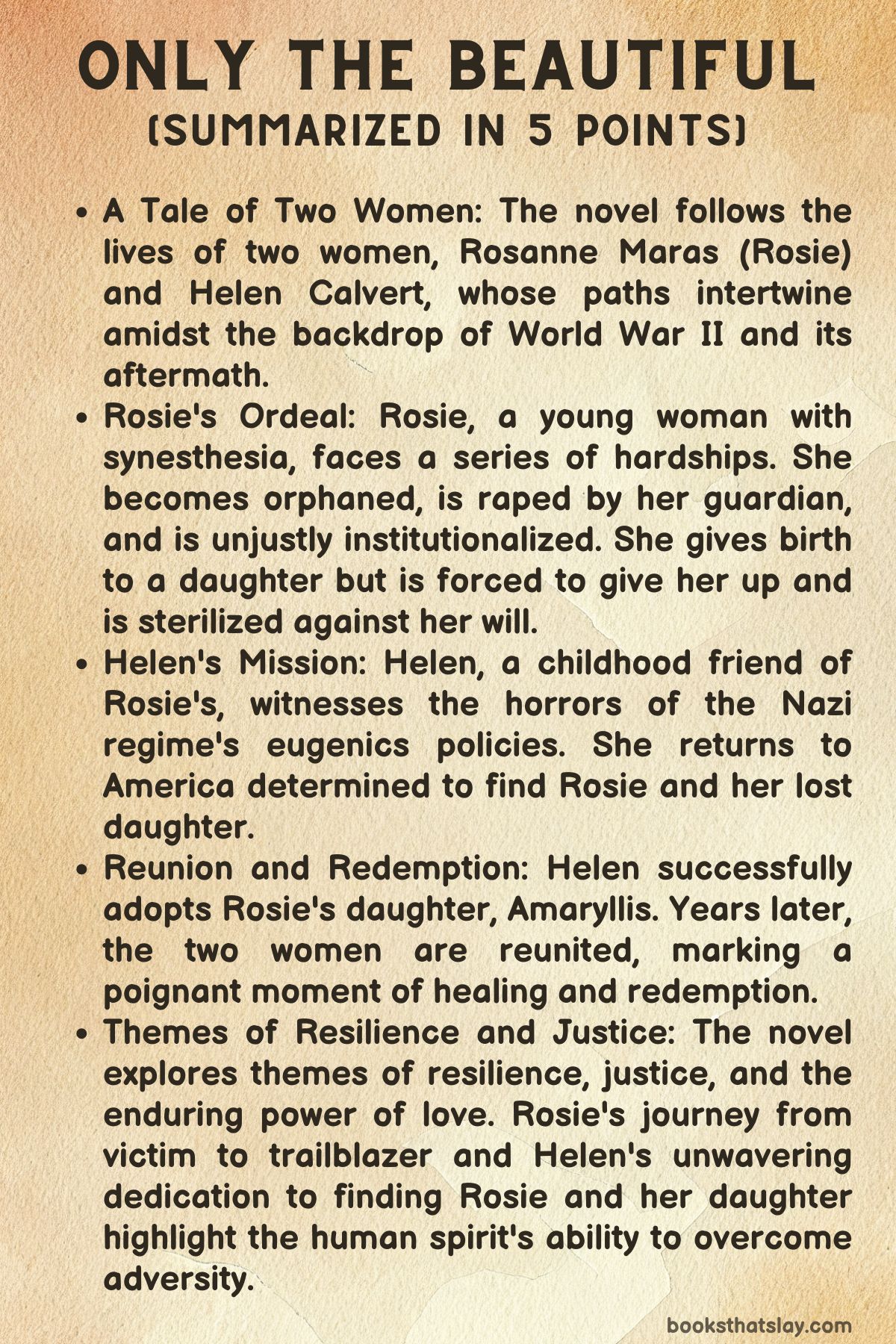

Only the Beautiful Summary, Characters and Themes

Only the Beautiful by Susan Meissner is a historical fiction novel set against the backdrop of World War II and its aftermath.

The story centers around two intertwined narratives: Rose, a young woman institutionalized for her synesthesia, and Helen, a friend who witnesses the horrors of war and becomes determined to find Rose and her lost child. Meissner’s novel delves into themes of trauma, resilience, and the enduring power of human connection.

Summary

In the heart of California’s vineyards, a young woman named Rosanne Maras, or Rosie, grapples with a unique neurological condition. Her world is painted in vivid hues, sounds and sights intertwined in a sensory symphony.

But her idyllic life is shattered when tragedy strikes, leaving her orphaned and at the mercy of her guardians. A cruel twist of fate leads to her unjust institutionalization and the heartbreaking loss of her newborn daughter.

Across the Atlantic, Helen Calvert, a childhood friend of Rosie’s, faces her own trials. As a nanny in Nazi-occupied Vienna, she witnesses firsthand the horrors of the regime’s eugenics policies.

The loss of a young girl to the chilling T4 program leaves her devastated.

Returning to America, Helen discovers the dark secret that haunts her sister-in-law’s vineyard.

The fate of Rosie, once a bright and hopeful young woman, fills her with a burning desire to right the wrongs of the past. Driven by a sense of justice and compassion, Helen sets out on a quest to find Rosie and her lost daughter.

Through a series of twists and turns, Helen’s search leads her to an orphanage where she encounters a familiar face. Amaryllis, Rosie’s daughter, has grown into a beautiful young girl.

With a heavy heart, Helen adopts her, cherishing the opportunity to provide her with a loving home.

Years later, fate intervenes once more. At a book signing event, Helen’s path crosses with Rosie’s.

Now known as Anne, Rosie has built a successful life as a researcher and author. The revelation of her daughter’s whereabouts brings about a long-awaited reunion, filled with tears, joy, and the healing power of love.

As the novel unfolds, we witness the resilience of the human spirit. Rosie’s journey from a victim of circumstance to a trailblazer in the field of neuroscience is a testament to her strength and determination. Helen’s unwavering dedication to justice and her unwavering love for Amaryllis highlight the enduring power of compassion.

Characters

Rosanne Maras (Rosie/Anne)

Rosie is the protagonist of Only the Beautiful, and her journey is central to the emotional arc of the story.

As a young girl with synesthesia, Rosie sees the world differently, but her condition, which should be a source of beauty and wonder, instead becomes a source of misunderstanding and mistreatment. Orphaned at the age of 16, she becomes a victim of circumstances beyond her control.

Rosie’s character is defined by her resilience, despite the overwhelming injustices she faces, from being raped and impregnated by her guardian to being institutionalized and sterilized without her consent. Throughout her time in the psychiatric institution, Rosie is forced to give up her daughter, Amaryllis, a heartbreaking loss that drives her later quest for understanding and self-worth.

Her synesthesia, which was initially a point of conflict, becomes a key to her empowerment, allowing her to seek knowledge and understanding about herself and her condition.

By the end of the novel, Rosie, now going by the name Anne, has found a new life through marriage and motherhood.

She represents strength and perseverance in the face of social and institutional cruelties, and her reunion with her daughter provides a deeply satisfying resolution to her struggles.

Helen Calvert

Helen’s character is the counterpoint to Rosie, offering a secondary perspective through which the novel explores the social issues of the time.

As a nanny living in Europe during World War II, Helen witnesses firsthand the horrors of the Nazi eugenics programs, which mirror, albeit on a more extreme scale, the practices being carried out in the United States.

The death of Brigitta, the child she cares for, under the Nazi T4 program, profoundly affects her. Helen’s story is driven by grief, guilt, and a fierce sense of justice.

When she returns to America, her discovery of what happened to Rosie compels her to act. Helen’s resolve to find Rosie’s daughter and adopt her speaks to her strong moral compass and compassion.

Her work as an advocate against eugenics further highlights her as a character dedicated to righting the wrongs of both personal and societal tragedies.

Her adoption of Amaryllis, and her eventual reunion with Rosie, completes Helen’s journey from bystander to active participant in the fight for justice, making her an instrumental figure in restoring the family Rosie had lost.

Celine Calvert

Celine is a complex character whose actions are deeply tied to the patriarchal and oppressive social norms of the time. As Truman’s wife and Rosie’s legal guardian after the death of her parents, Celine holds a position of power over Rosie, and her complicity in Rosie’s downfall is disturbing.

Although she is not directly responsible for Rosie’s rape, Celine’s decision to institutionalize her, rather than confronting her husband or protecting Rosie, speaks to the internalized misogyny and societal expectations that women of the era often faced.

Celine’s character reveals the ways in which women, too, could perpetuate the system of abuse and control. Her eventual confession to Helen about what happened indicates some level of guilt or awareness, but her passivity during the critical moments of Rosie’s life makes her a tragic figure, complicit in the systemic injustices of her time.

Truman Calvert

Truman is an embodiment of the abuses of power that permeate the novel. As the patriarch of the Calvert family and Rosie’s employer and guardian, his role as her protector is subverted by his predatory behavior.

His rape of Rosie is a key event that sets off the novel’s primary conflicts, and his subsequent evasion of responsibility through Celine’s complicity illustrates the double standards and lack of accountability for men in positions of power during this era.

Truman’s death in a combat training exercise removes him from the narrative before he can face any real consequences for his actions, a fact that highlights the overarching theme of institutional failure in delivering justice to the vulnerable.

Although his presence in the novel is brief, Truman’s actions create the traumatic events that shape Rosie’s life, and his character serves as a symbol of unchecked male authority and privilege.

Amaryllis

Although Amaryllis is not fully developed as a character due to her youth and separation from Rosie for much of the novel, she represents hope and the possibility of redemption. Her birth is a product of violence, yet her presence in the story becomes a catalyst for healing and reunion.

Adopted by Helen, Amaryllis grows up in a loving environment, protected from the harsh realities that her biological mother endured.

Her reunion with Rosie/Anne at the end of the novel symbolizes the restoration of a family fractured by societal abuses. Amaryllis serves as the embodiment of a new beginning, a connection to the future that transcends the pain of the past.

Dr. Anne’s Husband (Unnamed)

The neuroscientist who studies synesthesia and eventually marries Rosie/Anne plays a pivotal yet understated role in the resolution of the novel. His character is not developed in great depth, but he represents a figure of support and intellectual curiosity, contrasting with the exploitative figures from Rosie’s past.

His marriage to Anne signifies her reintegration into society and the validation of her unique neurological condition, which had previously been used against her.

By marrying someone who understands and accepts her condition, Rosie/Anne finds a sense of closure and peace, indicating that she has finally found a place where she can be accepted and loved for who she truly is.

Themes

The Dehumanization and Institutionalization of Neurodivergence within Eugenic Ideologies

One of the most significant themes in Only the Beautiful is the brutal dehumanization of those considered neurodivergent, particularly through the lens of eugenic practices in early 20th-century America. Rose’s synesthesia, a condition that allows her to experience vivid and unique perceptions of the world, becomes the basis for her institutionalization and the series of violations against her autonomy.

The novel shows that Rose’s synesthesia, which could have been regarded as an extraordinary and beautiful aspect of her life, is instead treated as evidence of madness. This reflects a historical tendency to pathologize and criminalize neurological differences, casting them as dangerous defects.

The psychiatric institution where she is confined represents a system that not only fails to understand but actively represses her humanity, treating her as an aberration to be controlled. This system mirrors the broader eugenic philosophy that permeates both the American and Nazi contexts within the novel, underscoring the idea that “undesirable” traits—be they physical, neurological, or behavioral—justify institutionalized cruelty.

Rose’s forced sterilization is a horrifying literal manifestation of this dehumanization, stripping her of reproductive agency in a grim reflection of how society attempts to ‘erase’ difference.

The Intersection of Sexual Violence and Powerlessness in the Context of Social Stigma

The novel intricately weaves the theme of sexual violence with the broader societal forces that oppress women, particularly those who are already marginalized by their health or social standing. Rose’s rape by Truman Calvert and its aftermath serve as a vehicle for examining the ways in which power, gender, and stigma intersect to silence and brutalize women.

As a vulnerable orphan under the care of the Calverts, Rose is preyed upon by a man who understands that her station and condition will make it easy to conceal the crime. This assault is not an isolated incident but part of a continuum of power dynamics in which women’s bodies are controlled and violated, first by men like Truman and later by institutions like the psychiatric hospital.

That Rose’s pregnancy—an outcome of this violence—becomes the catalyst for her further victimization speaks volumes about how women’s bodily autonomy is doubly compromised. Rather than being believed or supported, she is confined, sterilized, and treated as an object of pity or fear, her voice systematically erased.

The Legacy of Eugenics as a Transnational and Multigenerational Trauma

Meissner’s novel engages deeply with the theme of eugenics, not only as a practice but as a legacy of trauma that transcends national borders and generations. While much of the narrative takes place in California, the transatlantic nature of eugenic ideologies becomes painfully clear through the parallel storyline of Helen Calvert in Europe, where she witnesses the Nazi regime’s T4 program.

This juxtaposition of American and German eugenics demonstrates that these ideologies were not confined to one nation or time period; they represented a global movement intent on controlling and “purifying” the human population through often violent means. The novel’s portrayal of the Nazi euthanasia program, which targets children like Brigitta, serves as a harrowing reminder of how easily these ideologies can lead to genocide.

Helen’s mission to raise awareness about these atrocities upon her return to America parallels the work of many historical figures who sought to challenge eugenic policies in both Europe and the United States. However, the novel doesn’t frame eugenics as a relic of the past; through Rose’s sterilization and the systematic mistreatment of those deemed “unfit,” it demonstrates how these ideas continued to reverberate through American institutions long after World War II, leaving scars on those subjected to them.

The multigenerational aspect is evident in the fact that Amaryllis, separated from her mother at birth because of these ideologies, grows up as part of a different family. The reunion of Rose and Amaryllis years later hints at the possibility of healing but also reflects the long-lasting personal consequences of such state-sanctioned violence.

The Tension Between Personal Autonomy and Social Control in Shaping Identity

At its core, Only the Beautiful grapples with the tension between personal autonomy and the myriad forms of social control that shape identity and agency. Rose’s journey is one of a gradual reclamation of her autonomy after years of systemic oppression and personal violations.

Her institutionalization strips her of the ability to define her own identity, subjecting her instead to the labels and treatments imposed by doctors, social workers, and the state. The institutional control over her body, particularly through the act of forced sterilization, is emblematic of how society attempts to exert dominance over individuals deemed “other.”

However, Rose’s eventual discovery of her own condition through the doctor’s casual conversation at the hotel marks a pivotal moment of self-realization. This moment underscores the importance of knowledge and understanding in reclaiming autonomy.

No longer a passive victim of societal control, Rose begins to assert her identity, asking questions and seeking to understand the uniqueness of her neurological experience. Similarly, Helen’s narrative arc explores how individuals can resist social control by bearing witness and advocating for change.

Through her work, Helen carves out a space where personal narratives can challenge oppressive systems, suggesting that the reclamation of identity and autonomy is not only an individual journey but also a collective one.

The Complexities of Motherhood and the Generational Transmission of Trauma and Resilience

Motherhood, particularly in the context of trauma, loss, and resilience, is a central theme in Only the Beautiful, which explores the profound complexities of maternal relationships under duress. Rose’s forced separation from her daughter Amaryllis is an embodiment of both the violence inflicted by eugenic ideologies and the deep maternal grief that results from such policies.

Her longing for her child, combined with her acceptance that she may never see Amaryllis again, illustrates the painful emotional toll that these systems exact on mothers. However, the novel does not portray motherhood solely as a site of trauma.

The relationship that Helen builds with Amaryllis, as well as her efforts to honor Rose’s place as the girl’s biological mother, presents a more nuanced view of motherhood—one rooted in both loss and love. Helen’s decision to adopt Amaryllis but insist that she call her “Auntie” instead of “Mother” reflects her understanding of the complex emotional terrain of motherhood in this situation.

This choice shows how maternal bonds can transcend biological ties, while also acknowledging the importance of Rose’s identity as Amaryllis’s mother, even in absence.