Overdue by Stephanie Perkins Summary, Characters and Themes

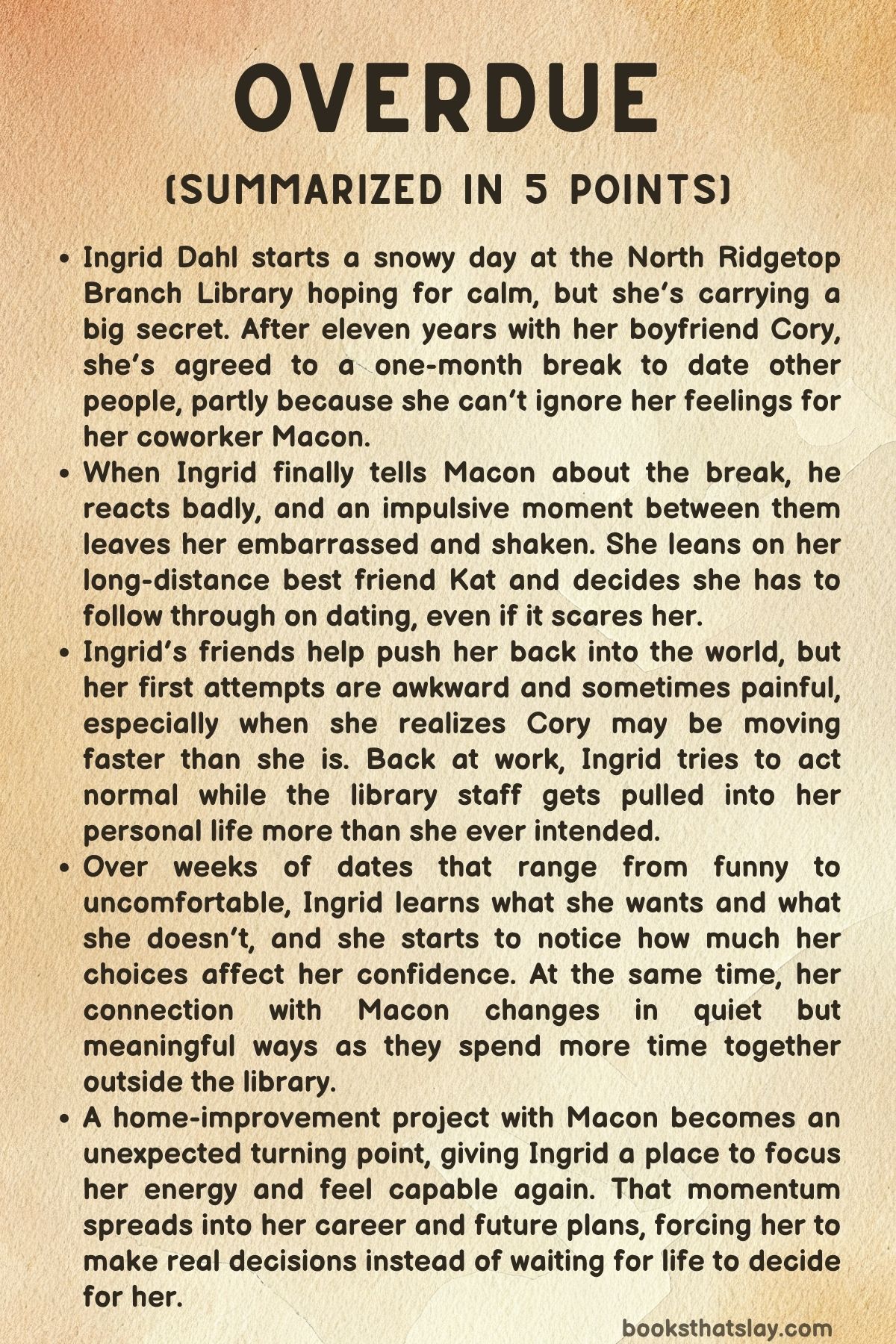

Overdue by Stephanie Perkins is a contemporary novel about change, self-discovery, and the unpredictable nature of love. The story follows Ingrid Dahl, a North Carolina librarian whose life is quietly upended when she agrees to take a one-month break from her long-term boyfriend, Cory, to explore what she might be missing.

What begins as a practical experiment spirals into a deeply personal journey through heartbreak, independence, and renewal. Through friendships, awkward dates, and unexpected emotional turns, Ingrid learns to rebuild both her confidence and her future, finding that sometimes love returns only after learning how to stand alone.

Summary

Ingrid Dahl’s story begins in the calm of the North Ridgetop Branch Library, where she works alongside her loyal yet cantankerous coworker, Macon Nowakowski. The two share a long-standing camaraderie built on humor, shared routines, and unspoken understanding.

Beneath Ingrid’s cheerful surface, however, lies turmoil. After eleven years with her boyfriend Cory, she has agreed to a one-month “break” in which both can date others before deciding if marriage is right for them.

Secretly, Ingrid hopes to explore her growing feelings for Macon.

When she confides in Macon, he bluntly calls the plan a mistake, though his concern hides deeper feelings. As snow begins to fall that evening, Ingrid misreads a moment of closeness and kisses him, only to be rejected in shock.

Humiliated, she drives home in tears and confides in her distant friend Kat, who urges her to move forward and actually participate in her so-called dating experiment.

That night, Ingrid ventures out with friends Brittany and Reza in a snowstorm, attempting to distract herself. When she spots Cory’s car outside a bar, already on a date, her hurt intensifies.

The evening collapses into emotional exhaustion, and she returns home feeling isolated and foolish. The next day’s heavy snowfall gives her time to hide, but Kat convinces her not to quit her job or run away.

When Brittany later offers to set her up with a divorced single father named Adam, Ingrid reluctantly agrees, determined to prove she can handle casual dating.

Returning to work, Ingrid faces Macon again. The encounter is painfully awkward, yet both pretend nothing happened.

His professional politeness and quiet care allow them to reestablish a fragile equilibrium. She soon meets Adam, whose nerves and divorced-dad charm seem harmless—until she learns he already knows about her relationship “break.” The date ends abruptly, and Ingrid feels once again like a failure at both love and self-experimentation.

At work, gossip about Ingrid’s romantic experiment spreads. Her coworkers react with disbelief, fascination, and unsolicited advice.

Pushed by Sue and Alyssa, Ingrid reluctantly creates a dating profile. Over the following weeks, she goes on a string of awkward, disappointing dates with men whose quirks range from self-absorption to outright rudeness.

She shares empty kisses but feels no real connection, while imagining Cory freely exploring new relationships. Her confidence erodes even as she tries to stay upbeat.

At the end of January, Ingrid meets Cory to assess their situation. Cory admits he’s been with other women, while Ingrid reveals she hasn’t slept with anyone.

Their conversation exposes mutual uncertainty, and Ingrid asks to extend their “break” another month. Cory agrees, relieved to delay commitment.

As February unfolds, Ingrid continues her dating misadventures and eventually sleeps with a man named Justin, an experience that brings momentary confidence. Yet when their chemistry fades, she recognizes that her search for meaning through others isn’t working.

Around the same time, she grows closer to Gareth Murphy, a polite library patron. On impulse, she invites him to join her for a hot-air balloon ride.

Their date is gentle, filled with nerves and quiet conversation, but it leaves Ingrid thoughtful rather than transformed.

Macon, meanwhile, becomes a steady presence again. Their conversations deepen as he helps her repaint and renovate parts of his house, transforming shared projects into a renewed friendship.

Through paint-stained hands and shared meals, their bond rekindles. Ingrid opens up about her lost ambitions and love for books, confessing that she once dreamed of owning a bookstore.

Macon encourages her to chase that idea, arguing that failure is not fatal. Slowly, their work evolves into a creative partnership that blurs the line between friendship and something more.

Encouraged by his belief in her, Ingrid applies for local business programs, drafts a business plan, and finally quits the library to open her own bookstore, Bildungsroman. The decision marks her first true act of independence.

When her landlord unexpectedly raises her rent, Ingrid scrambles for stability, eventually moving into a small, unfinished studio behind her friends’ home. Though Macon offers his spare room, she refuses, fearing to complicate their already complex relationship.

Over the months, Ingrid builds her bookstore and herself anew. Her friendship with Macon steadies into mutual admiration.

They work together on his house, repainting rooms, sharing late-night meals, and slowly dismantling the walls between them. When Macon confesses that he’s kept every photo she’s ever sent, they finally acknowledge their long-suppressed attraction.

Their relationship blossoms naturally from years of closeness, without grand declarations or drama.

As they settle into dating, Ingrid moves in with him before Thanksgiving. Their domestic life feels easy and real, filled with shared routines and quiet joy.

However, Macon’s family introduces new challenges—his mother, Lynn, struggles with severe anxiety, making social interactions difficult. A tense Thanksgiving dinner ends abruptly when Lynn panics, but Ingrid’s compassion strengthens Macon’s trust in her.

The holiday season brings further changes. Ingrid’s bookstore thrives through the winter rush, while Macon earns a promotion at work.

Ingrid’s sister Riley’s grand wedding approaches, stirring conversations about marriage that unsettle Ingrid. During her trip to Florida for the ceremony, she realizes she wants to marry Macon but worries he may not feel the same.

Upon returning home, Ingrid finds her bookstore flourishing and her relationship deeper than ever. When she finally admits her fears to Macon, he surprises her by confessing that he has long wanted to marry her but never found the right moment.

They confirm their shared vision of the future—no children, a small wedding, and a life built around books, conversation, and community.

As snow begins to fall outside the bookstore, Macon kneels and proposes without a ring, and Ingrid joyfully says yes. Their story closes at home, where Macon has filled the shelves with both their books and furnished the house with warmth and light.

In the glow of the season, Ingrid recognizes that what began as an uncertain “break” from love has led her back to it—stronger, wiser, and finally ready for a future that feels entirely her own.

Characters

Ingrid Dahl

Ingrid Dahl stands at the emotional core of Overdue, embodying the uncertainty of self-discovery and the slow courage required to rebuild one’s life. At the beginning of the story, she appears as a woman who finds comfort in structure—her librarian job, her long-term relationship, and her small North Carolina town.

Yet beneath that calm exterior, Ingrid struggles with stagnation and quiet dissatisfaction. The “break” from Cory represents not liberation but a hesitant act of rebellion against the passivity that has defined much of her adult life.

Her journey through awkward dates, humiliations, and eventual independence reflects a woman learning to occupy her own life rather than drift through it.

Ingrid’s emotional vulnerability is central to her growth. Her failed attempt to kiss Macon exposes both her impulsive longing and the deep ache of being unseen.

It also propels her into a painful but necessary confrontation with herself—forcing her to understand that love cannot replace self-understanding. Her compulsive cleaning, late-night introspection, and evolving passion for her bookstore dream become symbols of a woman slowly reclaiming her agency.

By the novel’s end, Ingrid emerges not as a flawless heroine but as a deeply human one—someone who has redefined stability on her own terms, finding partnership only after rediscovering her own worth.

Macon Nowakowski

Macon Nowakowski is one of the most complex and quietly magnetic figures in Overdue. A man grounded in ritual and subtle care, Macon embodies both emotional restraint and deep-seated affection.

His early rejection of Ingrid’s kiss is not cruelty but confusion—a symptom of his fear of disrupting a friendship he values more than he can admit. His meticulous habits, from his cleaning routines to his passion for home improvement, illustrate both control and vulnerability.

He seeks order as a defense against emotional chaos, a contrast to Ingrid’s restlessness.

As the story progresses, Macon’s guarded nature softens. His willingness to let Ingrid into his personal world—teaching her to sand, sharing memories of his childhood, cooking for her—reveals how love can unfold not through grand gestures but through steady acts of trust.

His relationship with his mother, Lynn, adds depth, showing the quiet burdens of caretaking and the patience that defines his life. Macon’s evolution lies in his acceptance that emotional connection requires risk.

By the novel’s close, when he fills the shelves with interwoven books and proposes without hesitation, Macon has transformed from a man who hides behind routines into one who creates a shared future with courage and tenderness.

Cory

Cory functions as both a mirror and a foil to Ingrid. Their eleven-year relationship, once comfortable and dependable, has decayed into emotional inertia.

Cory’s suggestion of a “break” under the guise of clarity exposes his immaturity and uncertainty about commitment. His actions—dating multiple women quickly after the break begins—underscore how differently he and Ingrid interpret freedom.

Yet he is not portrayed as cruel; rather, he is a man lost in the comfort of familiarity and afraid of what genuine self-examination might reveal.

Through Cory, Overdue explores the theme of emotional complacency. His presence haunts Ingrid throughout her journey, not as a villain but as a lingering possibility of what might have been if both had stayed passive.

Even his later conversation with Ingrid—urging her to speak honestly with Macon—reveals growth and lingering care. Ultimately, Cory represents a chapter of Ingrid’s life that needed to end for her to evolve.

His character reminds readers that endings, even painful ones, can be acts of quiet mercy.

Kat

Kat serves as Ingrid’s distant yet steadfast emotional anchor. Living in Australia, she bridges the physical and emotional isolation that defines Ingrid’s world at the story’s start.

Kat’s tough love and sharp honesty contrast Ingrid’s hesitations; she pushes Ingrid toward action, whether encouraging her to date again or face her mistakes. Though her role unfolds primarily through digital communication, Kat’s presence carries warmth and strength—she represents friendship as a form of emotional accountability.

Kat’s importance lies in how she keeps Ingrid grounded. Her guidance is pragmatic rather than sentimental, reminding Ingrid that change is uncomfortable but necessary.

In a story filled with failed romances and fleeting connections, Kat’s unwavering support stands as proof that chosen family can provide the courage to start anew.

Sue

Sue, Ingrid’s supervisor at the library, represents both institutional authority and maternal mentorship. Her belief in Ingrid’s potential—especially her insistence that Ingrid apply for library school—reflects her role as a quiet advocate.

Sue is pragmatic, professional, and sometimes stern, yet her encouragement comes from genuine care. She sees Ingrid as someone capable of leadership, even when Ingrid cannot see it herself.

Sue’s guidance also symbolizes the larger theme of opportunity versus fear. She nudges Ingrid toward ambition but ultimately respects her choice to pursue something different, demonstrating the novel’s belief that fulfillment is not found in prescribed paths but in personal authenticity.

Sue’s interactions underscore how mentorship, when rooted in empathy, can inspire self-belief without coercion.

Brittany and Reza

Brittany and Reza, the married couple who accompany Ingrid through her earliest forays into post-break dating, offer a compassionate yet humorous glimpse of domestic normalcy. Their presence highlights the stability Ingrid craves and fears.

They act as both protectors and witnesses—driving her through the snow, guiding her through awkward nights, and serving as gentle reminders of what steady love can look like.

Their relationship contrasts Ingrid’s fractured one, yet their kindness prevents that contrast from feeling judgmental. Through them, Overdue celebrates friendship as an act of quiet rescue.

They help Ingrid rediscover confidence in moments of shame and remind her that companionship, in any form, can be healing.

Gareth Murphy

Gareth Murphy enters the story later but plays a crucial role in rekindling Ingrid’s confidence and curiosity. A regular library patron, his unassuming charm and openness to adventure—agreeing to a spontaneous hot-air balloon ride—mirror Ingrid’s growing willingness to take emotional risks.

While their relationship doesn’t evolve into lasting romance, Gareth’s presence serves as a catalyst for Ingrid’s rediscovery of joy.

Through Gareth, Stephanie Perkins explores the idea that not all connections are meant to last; some exist to awaken dormant parts of ourselves. He represents freedom without recklessness—a necessary stepping stone between heartbreak and true emotional clarity.

Lynn Nowakowski

Lynn, Macon’s mother, appears late in the narrative but leaves a lasting impression as a woman marked by fragility and fear. Her inability to cross into the living room during Thanksgiving, due to her panic, reveals both her psychological struggles and the empathy that defines Macon’s relationship with her.

Lynn’s presence deepens our understanding of Macon—his patience, his protectiveness, and his quiet resilience all stem from years of caregiving.

She also serves as a reminder that love often involves caretaking and compromise. Through Lynn, Overdue highlights the weight of familial duty and how it shapes adult identity.

Her vulnerability humanizes Macon and, by extension, strengthens the bond between him and Ingrid.

Riley Dahl and Jess

Riley Dahl, Ingrid’s sister, and her fiancée Jess form a dynamic portrait of decisiveness and progress. Riley’s engagement to a professional basketball player contrasts sharply with Ingrid’s uncertain romantic life early in the novel, creating a sense of familial tension and internal comparison.

Riley’s straightforwardness—particularly her blunt questioning of Ingrid about marriage—forces Ingrid to articulate her desires rather than drift passively. Jess, though more understated, represents balance and grounded affection, complementing Riley’s strong personality.

Together, Riley and Jess embody a version of love that is confident and public, serving as both a mirror and motivation for Ingrid. Their presence reinforces one of the book’s central truths: that love looks different for everyone, but clarity—knowing what one wants—is the first step toward lasting happiness.

Themes

Self-Discovery and Identity

In Overdue, Ingrid’s journey unfolds as a complex exploration of self-identity, where personal growth is not sparked by dramatic events but by the quiet unraveling of long-standing complacency. At the start, she defines herself through external anchors—her relationship with Cory, her job at the library, and her carefully maintained routines.

These outward markers give her life a sense of predictability, yet they also suppress her capacity for self-definition. The “break” she agrees to with Cory becomes less about testing their relationship and more about confronting the uncomfortable truth that she has never truly known who she is outside of it.

Her awkward dates, professional uncertainties, and emotional missteps all mirror her attempt to rediscover her autonomy. Through the mundane settings of bars, libraries, and homes, Stephanie Perkins illustrates that identity is not reclaimed in isolation but through the act of confronting one’s fears of inadequacy and rejection.

Ingrid’s eventual decision to open her bookstore represents a symbolic rebirth—a conscious shift from being a caretaker of others’ stories to curating her own. It is not a sudden revelation but a cumulative awakening born of heartbreak, humiliation, and quiet persistence.

The theme underscores that self-discovery is not a clean process; it is messy, iterative, and often occurs in moments of domestic ordinariness. By the end, Ingrid’s sense of self extends beyond romantic attachment or external validation; it becomes rooted in purpose, creativity, and the confidence to shape a life that finally feels authored by her own choices.

Love, Vulnerability, and Emotional Maturity

The novel examines love not as an abstract ideal but as an evolving negotiation between vulnerability and self-respect. Ingrid’s interactions with both Cory and Macon highlight her gradual understanding that affection without honesty and mutual recognition cannot sustain intimacy.

With Cory, love has ossified into habit—a relationship defined more by endurance than passion. Their “break” exposes how emotional dependency can masquerade as commitment.

In contrast, Ingrid’s dynamic with Macon embodies the painful but necessary process of learning to love again with openness and courage. His initial rejection shatters her illusion of safety, forcing her to examine whether she values herself enough to endure emotional risk.

As their friendship rekindles and deepens into romance, Perkins portrays love as something that matures through humility, patience, and forgiveness. Macon’s careful boundaries, his gradual trust, and his eventual proposal all serve as emotional milestones in Ingrid’s reeducation about what genuine partnership entails.

The novel resists romantic clichés by portraying vulnerability as a moral and emotional strength rather than a weakness. Love becomes meaningful only when both partners confront their flaws and fears without pretense.

Ingrid’s evolution—from impulsive yearning to conscious emotional generosity—marks her growth from someone who seeks to be loved into someone capable of loving fully. The theme ultimately suggests that maturity in love is measured not by intensity but by the ability to remain kind and honest, even in moments of pain or doubt.

Independence and Female Agency

Perkins places Ingrid’s journey within the broader theme of female independence, portraying it through the lens of everyday resilience rather than overt rebellion. Ingrid’s decision to stay in her job, attend business school, and eventually open her bookstore signifies a departure from passive contentment into active agency.

Her life is shaped by quiet acts of defiance—choosing to date despite failure, rejecting self-pity after humiliation, and asserting control over her future. The book resists presenting independence as a rejection of love or domesticity; rather, it emphasizes coexistence between emotional and professional fulfillment.

Ingrid’s evolution contrasts sharply with the women around her—her sister Riley’s glamorous engagement, Sue’s managerial pragmatism, and Kat’s distant mentorship—each representing different modes of navigating womanhood. Through Ingrid, Perkins reclaims the narrative of female growth from external judgment and societal timelines.

Independence becomes a process of choosing oneself repeatedly, even when the world expects conformity. The establishment of the bookstore, Bildungsroman, stands as the culmination of this theme: a literal and metaphorical house of stories where Ingrid’s voice finally occupies space.

The novel presents her independence not as isolation but as authorship—the right to narrate her own life, mistakes included.

Fear, Failure, and the Possibility of Renewal

Throughout Overdue, fear operates as both a constraint and a catalyst. Ingrid’s story is filled with moments of avoidance—her reluctance to confront Macon after rejection, her hesitation about library school, and her fear of professional inadequacy.

Yet each of these fears propels her toward self-renewal once she acknowledges them. Perkins portrays failure not as an endpoint but as a necessary stage in the cycle of growth.

Ingrid’s mortifying experiences, from failed dates to emotional breakdowns, dismantle her illusions about control and perfection. These experiences strip her of false confidence but leave room for authentic courage to emerge.

The act of renovating Macon’s home and later launching her bookstore symbolizes renewal through labor—literal rebuilding as emotional reconstruction. Every brushstroke, every repaired wall becomes a metaphor for healing, showing that progress often occurs through repetitive, unglamorous work.

The theme culminates in Ingrid’s realization that renewal requires embracing uncertainty rather than conquering it. Her acceptance of imperfection—her own and others’—marks her shift from fear to faith, from clinging to the past to constructing a future.

Perkins suggests that renewal is not granted by circumstance but earned through endurance and an openness to transformation.

Home, Belonging, and Shared Spaces

The motif of home runs deeply through the narrative, functioning as both physical setting and emotional anchor. The library, the micro-studio, Macon’s house, and finally the bookstore each represent stages in Ingrid’s search for belonging.

These spaces evolve from sites of confinement to places of creation and connection. In the early chapters, the library embodies safety and stagnation—a sanctuary that shields Ingrid from emotional chaos while also limiting her growth.

The move to Macon’s home and the renovation projects that follow turn domestic space into a metaphor for intimacy and renewal. As Ingrid helps restore the house, she simultaneously rebuilds her capacity to trust and inhabit love.

The culmination in Bildungsroman, her bookstore, fuses professional and personal belonging: it becomes a home not just for herself but for stories, readers, and the community that surrounds her. Perkins uses these shifting settings to question what “home” truly means—whether it is a place, a person, or a sense of peace within oneself.

By the end, home becomes a shared achievement, one built through care, mutual respect, and the courage to begin again. It stands as both a conclusion and a beginning, where belonging is no longer sought but consciously built.