Paper Doll: Notes from a Late Bloomer Summary and Analysis

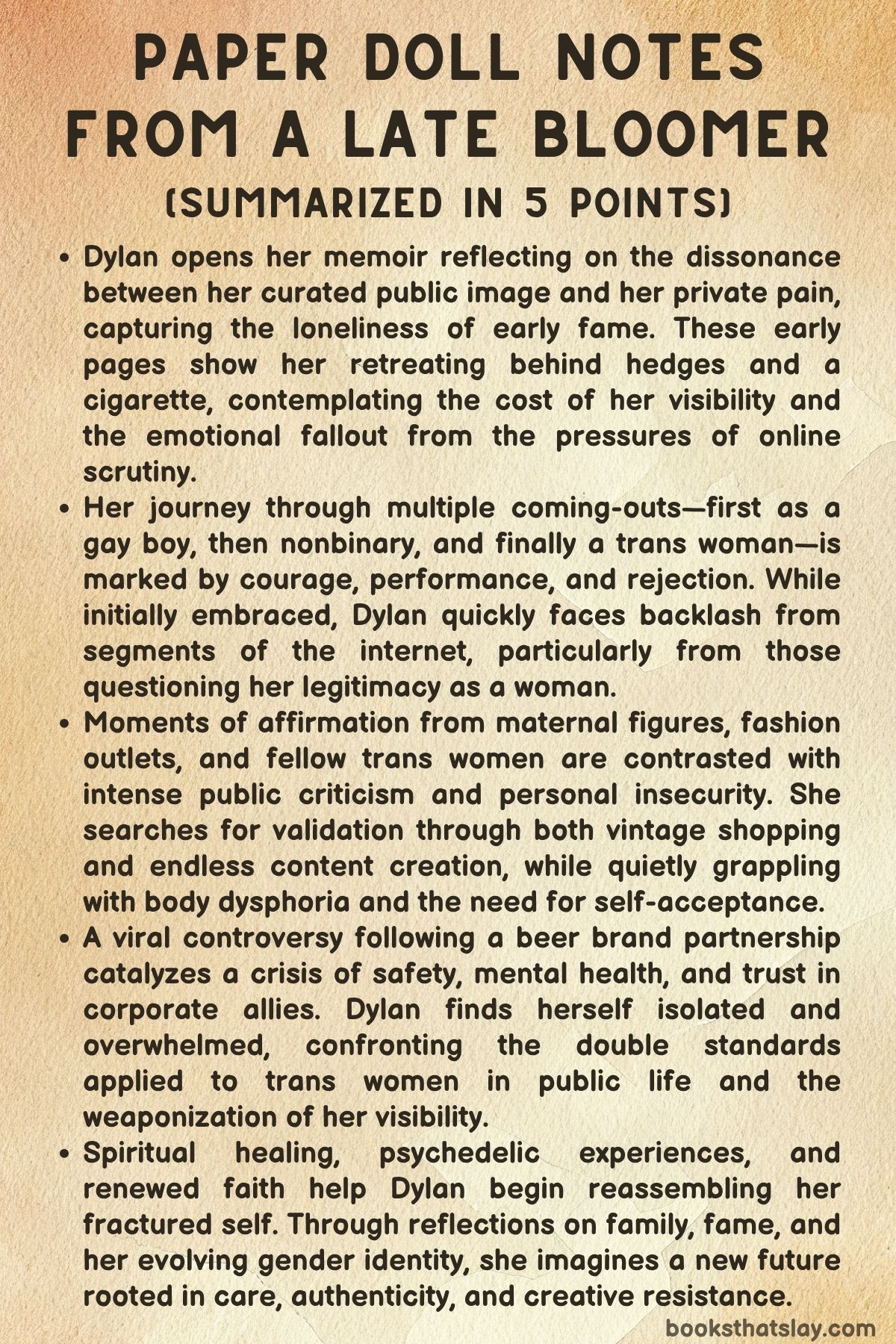

Paper Doll: Notes from a Late Bloomer by Dylan Mulvaney is a bold, intimate, and humorous memoir chronicling the author’s multifaceted journey through gender identity, fame, public scrutiny, and personal healing. Known for her viral “Days of Girlhood” TikTok series, Dylan uses this book to pull back the curtain on her private moments—from childhood gender confusion to navigating the overwhelming spotlight of internet stardom.

Through candid stories, emotional reckonings, and moments of joy and pain, she confronts both the beauty and the brutality of living authentically in a society that isn’t always ready for it. The result is a powerful account of growth, visibility, and the emotional complexity of coming into one’s own.

Summary

Paper Doll: Notes from a Late Bloomer begins with Dylan Mulvaney in a moment of isolation, perched on her porch, smoking a slim cigarette, and contemplating the dichotomy between her curated internet persona and her raw emotional truth. This opening lays the groundwork for a deeply introspective exploration of identity, transition, and survival under public scrutiny.

She describes the emotional intensity of coming out for the third time—first as a gay boy, then as nonbinary, and finally as a trans woman. Her coming-out video, filled with emotion and theatre, is met with immediate backlash from some corners of the internet, particularly from trans-exclusionary radical feminists.

This pain is compounded by Dylan’s internal struggle to gain acceptance from the very group she wishes to join: women.

Early in the memoir, Dylan turns to Keesh, a long-time maternal figure in her life, for comfort. They go vintage shopping, and though the activity is grounding, Dylan is constantly battling the digital noise from her phone.

She becomes obsessed with social media validation, doomscrolling through hate and praise, and trying to salvage her image by posting more content. These moments underscore the psychological toll of being constantly perceived and the challenge of maintaining authenticity amid pressure.

On the third day after her coming out, a surge of support emerges online, balancing the vitriol. This digital whiplash leaves Dylan both uplifted and wary, as she realizes the internet amplifies extremes—both love and hate.

Dylan starts to lean into her femininity, sometimes through symbolic gestures like buying tampons to signal solidarity with cis women. Even these efforts are met with scrutiny, highlighting the impossibility of satisfying everyone.

She opens up about her “lady beard,” a source of insecurity, and discusses her choice to present as feminine even while struggling with facial hair. This choice to embrace imperfection becomes a quiet act of rebellion and honesty.

Her vulnerability about dysphoria, laser treatments, and body image dismantles narrow expectations placed on trans women and reframes femininity as expansive rather than prescriptive.

As her visibility increases, Dylan lands opportunities to attend high-profile events like the Fashion LA Awards. She finds joy in dressing up, being styled, and mingling with icons such as Gigi Gorgeous and Kathy Hilton.

These experiences offer moments of validation, but they also exist alongside painful ones, like being denied a red carpet appearance or being misgendered by celebrities she once admired. Her fame hits a breaking point during the controversy surrounding her partnership with a beer company.

What begins as a lighthearted ad becomes a political flashpoint. Dylan is bombarded with death threats, hateful commentary, and corporate abandonment.

The fallout from “Beergate” leads her to feelings of dissociation, fear, and deep emotional collapse.

To make sense of this trauma, Dylan turns inward. She begins to interrogate her sexuality, revisiting past romantic experiences and redefines herself as queer.

Her exploration is not just about labels but about carving out emotional and physical safety in relationships. She shares vulnerable moments about learning to tuck and being criticized for not doing so.

Rather than buckle under that pressure, Dylan decides to share her experiences publicly, leaning on a small group of trans women for emotional and practical support. This circle becomes a source of strength, offering both education and community.

Her family relationships reflect the complexity of generational shifts in understanding gender. Her father, once emotionally distant, affirms her identity with surprising warmth.

Her mother, Dana, is a more conflicted figure, shaped by religious beliefs and maternal fear. Dylan doesn’t sugarcoat their rocky journey, instead opting to show how love and misunderstanding can exist simultaneously.

The memoir navigates their strained but evolving relationship, touching on moments of hurt as well as hope.

The story deepens as Dylan begins to seek healing outside the online world. She checks into a wellness retreat and eventually travels to Peru for an ayahuasca ceremony.

These experiences are transformative, helping her reconnect with childhood trauma and confront deep-seated fears. In a vision during the ceremony, she receives a powerful message: her purpose may lie in motherhood—not necessarily in the biological sense, but in the act of nurturing and protecting.

This spiritual encounter reframes her journey from one of survival to one of service and legacy.

In the aftermath of this emotional and spiritual awakening, Dylan visits a Unitarian church where she finds a community that welcomes queer identities. The space, filled with openness and acceptance, reintroduces her to the idea of a God who embraces her fully.

This rekindling of faith does not come with doctrine but with personal reclamation. For Dylan, religion becomes less about dogma and more about possibility—a way to make peace with the Catholic guilt that once haunted her.

As the narrative progresses, Dylan redefines what celebrity means to her. Through a concept called “Celebrity 2.0,” developed with guidance from a non-traditional spiritual mentor, she lets go of the performative mask required by internet culture. This shift allows her to embrace her full self—messy, joyful, scared, and powerful.

She contrasts encounters with authentic allies against those with performative supporters, learning to protect her energy and set boundaries.

The memoir ends not with closure but with clarity. Dylan does not claim to have everything figured out, but she asserts her right to take up space—imperfect, joyful, and evolving.

She reclaims her voice not just as a trans woman, but as a human being worthy of love, community, and self-respect. The tutu she longed to wear as a child becomes a symbol not of performance, but of presence.

She belongs now, and she no longer needs anyone’s permission to say so.

Paper Doll: Notes from a Late Bloomer is, at its core, a chronicle of becoming—messy, painful, public, and sacred. Through viral fame, mental health crises, spiritual healing, and personal revelations, Dylan Mulvaney offers a story not just of transition, but of transformation.

Her memoir is a declaration: to live truthfully, even when it’s terrifying, is the most radical form of joy.

Key People

Dylan Mulvaney

Dylan Mulvaney is the vivid, beating heart of Paper Doll: Notes from a Late Bloomer, and her characterization is as layered and expansive as the memoir itself. From the outset, Dylan presents herself not as a static protagonist, but as a constantly evolving narrative force shaped by social media virality, personal trauma, and a relentless desire for self-authenticity.

Her journey of coming out—first as gay, then nonbinary, and finally as a trans woman—demonstrates a deep, introspective interrogation of identity that refuses linear simplification. Dylan is both whimsical and devastatingly honest, delighting in costumes, girlhood rituals, and self-performance, even as she confronts the cruelty of online backlash, loneliness, and dysphoria.

Her emotional world is deeply textured: she finds joy in pink feathered gowns and birthday cakes, yet grieves over her Catholic school trauma, fractured maternal ties, and the isolating weight of public scrutiny. Dylan is also deeply reflective, whether reckoning with the symbolic weight of tampons or undergoing spiritual transformation through ayahuasca visions.

She is fiercely committed to self-expression, often at great personal cost, and her vulnerability becomes an act of political resistance. Dylan’s longing—for motherly love, for peer acceptance, for safe belonging—is never fully resolved, but her resilience, humor, and determination to live joyfully as a trans woman shine throughout the memoir.

Keesh

Keesh emerges as a maternal, grounding presence in Dylan’s whirlwind of viral fame and emotional fragility. Unlike the performative or conditional affections of others in Dylan’s life, Keesh offers something rare and constant: unconditional acceptance.

She represents a chosen family figure who not only affirms Dylan’s femininity but also embodies warmth, comfort, and everyday ritual—like vintage shopping—that counters the toxic rhythm of online validation. Their shared moments offer Dylan relief from doomscrolling and remind her of the affirming spaces that can exist outside of the internet.

Keesh, in many ways, fills the maternal void left by Dylan’s complicated relationship with her own mother. Her presence doesn’t demand perfection or performance; instead, she simply shows up with compassion and steadiness, reminding Dylan—and the reader—that womanhood is also about shared moments, small joys, and community.

Dana (Dylan’s Mother)

Dana is portrayed with nuance and emotional complexity, reflecting a deep maternal bond riddled with tension, religiosity, and miscommunication. Initially resistant to Dylan’s transition, Dana’s disapproval is rooted in her faith and traditional views, creating a chasm between mother and daughter that is as spiritual as it is emotional.

Her discomfort with trans identities, especially the idea of trans children, is devastating for Dylan, who craves her mother’s love and understanding. Yet the memoir also depicts Dana as a figure capable of growth—tentative, slow, and painful.

Their journey toward mutual understanding is neither linear nor fully resolved, but it illustrates the broader generational and cultural tensions faced by many trans individuals. Dana is not a villain; she is a mother navigating her own limitations, caught between doctrine and daughter, love and fear.

Her presence in the memoir amplifies Dylan’s vulnerability and underscores the deep emotional labor required to seek acceptance from family while crafting a new identity.

Dylan’s Father

In contrast to Dana, Dylan’s father surprises both Dylan and the reader with a more immediate and unconditional form of acceptance. A politically conservative man, he breaks expectations by proudly affirming Dylan as his daughter—a moment that Dylan describes as deeply healing and emotionally significant.

His acknowledgment becomes a pivotal emotional anchor in Dylan’s story, suggesting that transformation and acceptance can come from the most unexpected places. While not as frequently present in the memoir’s narrative as other characters, his symbolic weight is immense.

His ability to step into a new role in Dylan’s life—one that defies his political alignment—offers a portrait of familial love that transcends ideology and becomes an emblem of possibility in an otherwise harsh world.

Isadora and Lina

Isadora and Lina function as peer guides and emotional supports within the sisterhood of trans womanhood. They are more than just friends; they are mentors and co-travelers, teaching Dylan the rituals and strategies of survival in a transphobic society.

Whether it’s the practical art of tucking or the emotional labor of processing microaggressions, their presence affirms Dylan’s belonging in a community that understands her pain and joy without explanation. These women offer solidarity, shared wisdom, and humor in the face of public spectacle and private vulnerability.

They represent the power of chosen kinship and highlight how vital intergenerational and communal support is for trans individuals navigating visibility and scrutiny.

Mory

Mory, the spiritual guide and unlicensed life coach, becomes a catalyst for Dylan’s evolution beyond traditional notions of fame and femininity. Through Mory, Dylan formulates the concept of “Celebrity 2.0,” which encourages vulnerability, authenticity, and a rejection of performative gloss. Mory’s influence pushes Dylan toward self-inquiry and away from the need to appease mainstream norms.

Their philosophical and emotionally rich conversations underscore the memoir’s deeper thematic explorations of identity, purpose, and transcendence. In a memoir filled with dramatic highs and lows, Mory introduces a quieter but no less powerful path toward spiritual alignment and self-trust.

Analysis of Themes

Identity as Fluidity, Performance, and Self-Possession

Dylan Mulvaney’s account reveals identity not as a fixed state but as an evolving act of self-construction shaped by public scrutiny, personal intuition, and resilience. Her narrative follows a trajectory through multiple coming-outs—gay boy, nonbinary individual, and ultimately a trans woman—which underscores how identity can be both cumulative and redefined over time.

Each revelation builds upon the last but also resists linearity, showing that understanding oneself is often nonlinear and reactive to context. The “Days of Girlhood” project, while celebratory, becomes emblematic of this complex identity formation: Dylan is simultaneously documenting her transition for herself and performing it for a vast online audience.

The pressure to “get it right” for both cis and trans viewers fractures her sense of authenticity. Her decisions—buying tampons, embracing facial hair, or choosing not to tuck—are weighed down by the expectation to represent an entire community.

This exposes how identity, especially in the context of marginalized existence, can be burdened by the need for perfection. Yet, Dylan reclaims her narrative by affirming that imperfection, ambiguity, and even contradiction are valid modes of existence.

She shifts from people-pleasing and theatrical masking to what she and her mentor call “Celebrity 2. 0”—a model of being that privileges truth over optics.

This move toward radical honesty allows Dylan to transition not just in gender, but in self-possession, where she stops auditioning for acceptance and instead reclaims authorship of her life. Identity, in her telling, becomes not a stable noun but a living verb—unfolding, reacting, and surviving.

The Violence and Liberation of Visibility

Visibility, while often positioned as a tool of empowerment, operates in Paper Doll: Notes from a Late Bloomer as both weapon and balm. Dylan’s early elation at being seen—on red carpets, on social media, in collaborations—gives way to the disorienting reality of being surveilled, criticized, and even threatened.

Her transition becomes a battleground for ideological conflicts, especially following the fallout from “Beergate,” which places her at the center of a culture war. What was once joyful documentation is now weaponized content.

She experiences the paradox of being hyper-visible yet profoundly misunderstood and alone. Her celebratory Day 100 ice cream moment, filmed and adored by strangers online, is starkly contrasted by the absence of any real-life companionship.

This duality illustrates the way digital fame can simulate community while deepening physical isolation. Dylan’s navigation of this paradox forces her to reexamine what visibility means—to be seen but not known, to be watched but not held.

The backlash also reveals how society punishes trans women for simply existing in public, especially those who refuse to conform to rigid, sanitized expectations of femininity. In contrast, Dylan’s ultimate embrace of vulnerability, her defiance in showing her facial hair, and her sharing of private despair shift visibility from spectacle to resistance.

Rather than retreating from the public eye, she chooses to remain, but on her own terms. Visibility becomes less about performance and more about testimony—a form of living protest that honors pain without being defined by it.

The Burden and Beauty of Public Girlhood

Dylan’s girlhood is both a reclamation and a construction, shaped by nostalgia, longing, and social performance. She never had a conventional girlhood, so her viral “Days of Girlhood” becomes both celebration and compensation.

She meticulously curates her femininity, sometimes exaggerating it—performing ballet, buying tampons—to connect with a world she had previously been denied. Yet even these gestures are parsed and politicized by audiences who interpret her femininity through rigid binaries.

The pressure to be the “right” kind of woman forces her into impossible negotiations: be soft but not performative, visible but not provocative, joyful but not naive. This public-facing girlhood, while empowering, comes with constant surveillance.

Every outfit, every gesture becomes a battleground. Still, Dylan finds community and mentorship through other trans women and affirming figures like Keesh and Gigi Gorgeous, who validate her femininity without condition.

These relationships provide emotional scaffolding for her to claim a girlhood that is self-defined rather than inherited. By choosing joy, even in the face of mockery, Dylan asserts that trans girlhood is not derivative—it is real, sacred, and worthy of recognition.

Her narrative challenges the idea that womanhood is bound by biology or linear time. Instead, she proves that girlhood can be chosen, performed, and lived as a conscious act of autonomy.

In reclaiming this timeline, Dylan not only heals past wounds but also offers a radical reimagining of what it means to come of age.

Healing, Spirituality, and the Search for Wholeness

Healing in Dylan’s story is neither swift nor linear. It involves a complex interplay of physical transition, spiritual reawakening, mental health support, and reconnection with community and self.

After experiencing the psychological toll of online hate and corporate betrayal, Dylan finds herself emotionally fractured and physically endangered. She turns to unconventional healing—psychedelic therapy in Peru, reconnection with childhood memories, and eventual return to a queer-affirming spiritual community.

Her use of ayahuasca becomes not just a moment of release but of revelation: she reconnects with a younger version of herself and is shown that her greater purpose might include motherhood—not necessarily biological, but spiritual and communal. This reimagined purpose reframes her pain as a portal to empathy.

It’s not a justification for trauma but a reorientation. Dylan begins to see herself not as a casualty of fame but as a potential source of maternal care for others in the queer community.

This is echoed in her return to a Unitarian church that embraces her womanhood and queerness, signaling that faith, long a source of guilt, can become a sanctuary. Healing is found not in erasure of pain but in its honest acknowledgment and creative transmutation.

Rather than seeking to return to a pre-traumatized self, Dylan constructs a more integrated identity—one that can hold both joy and sorrow, both celebration and scars. Her story suggests that healing is not the closing of a wound, but learning to live—and live generously—while it remains tender.

Family, Generational Change, and Conditional Love

The familial dimension in Dylan’s memoir adds a layer of emotional complexity, exposing how queerness can destabilize and ultimately transform family dynamics. Her father, a conservative man, becomes an unlikely source of acceptance, proudly calling her “daughter” and affirming her transition in small but profound ways.

This acceptance is particularly moving because it comes from someone who once might have been presumed an adversary. In contrast, Dylan’s mother, Dana, is a more challenging figure—loving yet deeply embedded in religious doctrine that conflicts with Dylan’s identity.

Their relationship, marked by disapproval, tension, and reluctant dialogue, exemplifies the pain of conditional love. Yet Dylan doesn’t portray these relationships as static or reductive.

Instead, she opens space for ambivalence, evolution, and slow change. The love she receives is not always clean or ideal, but it is often genuine and growing.

Her reflections on generational divides reveal the emotional labor queer people must perform to maintain bonds with family while safeguarding their own mental health. Dylan doesn’t demand perfection from her parents but yearns for presence, recognition, and emotional accountability.

In showing both the breakthroughs and the failures, she paints a portrait of family as a site of potential transformation rather than fixed roles. This nuance is essential to the memoir’s emotional impact: reconciliation is possible, but it is often messy and incomplete.

Still, the moments of connection—her father’s pride, her mother’s grappling—suggest that even the most resistant relationships can become vessels for growth and mutual learning.