Penance by Eliza Clark Summary, Characters and Themes

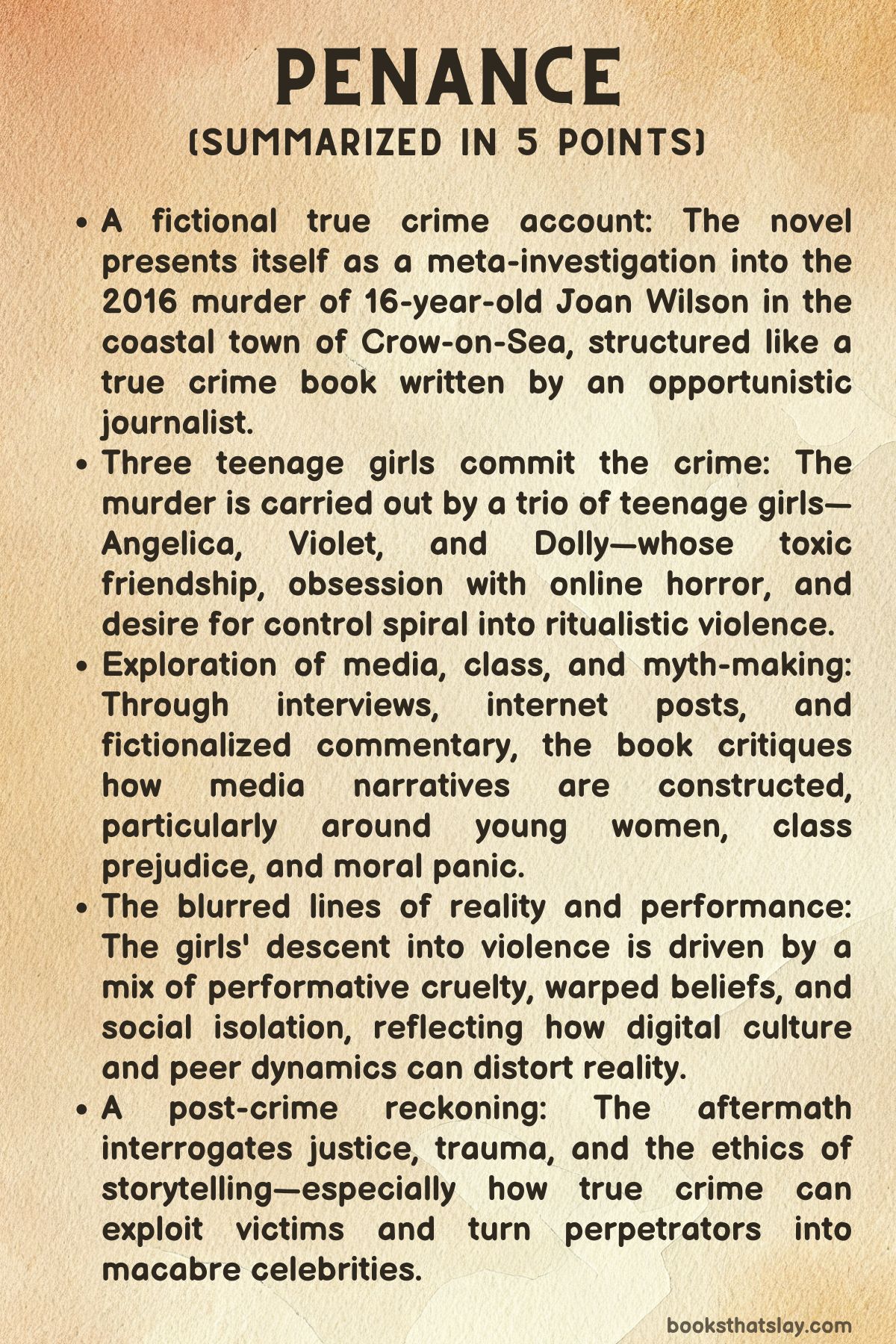

Penance by Eliza Clark is a blisteringly original and haunting work of fiction that dissects the obsession with true crime, girlhood, and modern myth-making.

Told through the lens of a pseudo-journalist compiling a book on the brutal murder of a teenage girl, Penance blurs the line between fiction and documentary. Set in the decaying coastal town of Crow-on-Sea, the story brings together interviews, invented footnotes, online posts, and narrative fragments to explore a crime committed by three girls. Clark’s chilling, satirical, and deeply unsettling novel examines the allure of violence, the danger of storytelling, and the societal impulse to explain the inexplicable.

Summary

Penance opens with the harrowing 2016 murder of Joan Wilson, a 16-year-old girl from the gloomy seaside town of Crow-on-Sea in North Yorkshire. The case shocks the nation not only because of its brutality—Joan is beaten, tortured, and set on fire—but also because her killers are three teenage girls.

The story is told through the voice of a journalist assembling a book years after the crime, blending interviews, theories, and fictionalized “evidence” to reconstruct what happened, and why.

In the section GIRL A, we are introduced to the first perpetrator, Angelica Stirling-Stewart, a girl of privilege with a politician father. Angelica emerges as a cold, manipulative figure who exerts psychological control over her peers. Though intelligent and poised, she is emotionally vacant. The media latches onto her posh background, fueling a moral panic about “killer girls” and class disparity.

HALLOWEEN delves into the group’s early obsession with horror, death, and internet lore. Their interest in violence becomes performative—something that bonds them and sets them apart from their peers. Halloween is the backdrop for increasingly disturbing “games” and rituals. This section emphasizes how their obsession with notoriety and aesthetics of evil warps their perception of morality.

GIRL B centers on Violet Hubbard, the most morally conflicted of the trio. She is awkward, anxious, and deeply immersed in online spaces where dark content is normalized. Violet’s need to belong makes her susceptible to the influence of Angelica and Dolly (Girl C), though she often second-guesses their actions. Violet seems less culpable, but her passivity and silence play their own part in what unfolds.

In THE WITCH HAMMER, the girls begin to craft a delusional mythos inspired by occult texts, conspiracies, and pseudo-history. They position Joan—who had once been part of their group but distanced herself—as a corrupting force, a symbolic “witch” to be punished. Their logic collapses into fantasy, but their conviction grows, and their imagined mythology becomes deadly serious.

CHRISTMAS highlights the emotional and psychological disintegration of the group during the festive season. While the world celebrates, the girls sink deeper into alienation and fantasy. The contrast between holiday joy and the simmering violence within the trio intensifies the unease. They plot increasingly specific forms of revenge against Joan, whom they now vilify in increasingly surreal terms.

FORMERLY KNOWN AS GIRL D shifts to Jayde Spencer, a peripheral figure wrongly implicated due to her proximity to the others. Her life is upended by rumors, social media backlash, and police incompetence. Jayde’s story reveals the broader damage inflicted by a justice system quick to judge and a public eager for scapegoats.

MAD BOB adds texture to the setting by focusing on a local eccentric whose unsettling presence mirrors the town’s own dysfunction. Through his folklore, the reader gains a sense of Crow-on-Sea’s rot: once a thriving community, now hollowed out, paranoid, and bitter—a breeding ground for discontent and darkness.

In SPRING EQUINOX, the girls finalize their plan. What began as symbolic ritual now morphs into real intent. The equinox—a time of “balance”—becomes their chosen date for “purging” Joan. They script the event with theatrical precision, deluded into believing in its moral necessity.

GIRL C zooms in on Dolly Hart, perhaps the most volatile of the trio. Charismatic and damaged, Dolly has a chaotic home life and a twisted sense of loyalty. She becomes the engine of violence, pushing the group toward action with a chilling lack of empathy. Her psychological manipulation is profound, casting her as the emotional center of the crime.

In LEAVING, the murder is finally enacted. Joan is abducted, tortured, and set ablaze in a seaside chalet. Her attempt to escape—on fire, begging for help—is a horrifying crescendo. The girls flee, numbed and in shock.

The final chapter, AFTERMATH, explores the media circus, the trial, and the long-term impact. Joan’s mother grieves in silence while the girls become tabloid icons. The journalist narrator reflects on true crime culture, questioning how stories like this are consumed, commodified, and remembered. The book ends not with answers, but with troubling questions about complicity—both societal and personal.

Characters

Angelica Stirling-Stewart

Angelica Stirling-Stewart, known as Girl A, is initially portrayed as a privileged and manipulative character. Coming from a wealthy family with political ties, she is the driving force behind the group of girls and is often seen as controlling.

Throughout the novel, Angelica’s ability to influence the others becomes more evident, showcasing her dominance within the trio. Her character is deeply complex, reflecting a sense of entitlement, a desire for power, and a lack of empathy.

She plays a pivotal role in shaping the group’s disturbing worldview, often blurring the lines between fantasy and reality. Her behavior is marked by a need to assert control over those around her, which makes her a central figure in the tragic events that unfold.

Violet Hubbard

Violet Hubbard, or Girl B, is quieter and more introspective compared to the other girls. She is deeply affected by social anxiety and struggles with her sense of self, finding solace in digital spaces.

Violet’s character presents a moral conundrum; she is portrayed as impressionable and malleable, often following Angelica and Dolly without much resistance. Despite her internal struggles, Violet is reluctant to take responsibility for the events leading to Joan’s murder, which adds to the ambiguity of her character.

She is both a victim of the group’s toxic dynamics and a participant in its horrifying actions. Violet’s role in the story is crucial as she embodies the vulnerability of someone caught in the gravitational pull of a dangerous friendship, unable to escape the collective delusion.

Dolly Hart

Dolly Hart, or Girl C, is the most enigmatic and manipulative of the three girls. Her background is marked by instability and neglect, which may have contributed to her cruel and charismatic personality.

Dolly is portrayed as the ringleader of the group, her influence over Angelica and Violet stronger than any of the other girls realize. Her psychological complexity is chilling, as she seems to derive satisfaction from controlling and tormenting those around her.

Dolly’s manipulative nature is central to the story, as she masterminds much of the girls’ shared delusions, including their belief that Joan is a witch deserving of punishment. Her leadership within the group highlights the darker aspects of human behavior, especially when unchecked by empathy or moral consideration.

Joan Wilson

Joan Wilson, the victim of the girls’ violent actions, is a tragic figure in the story. While she is not a central character in the same way the girls are, her role is pivotal.

Joan is depicted as a complex individual whose tragic fate brings the darker aspects of the other girls to light. Her character symbolizes the vulnerability of those who become scapegoats for others’ psychological turmoil.

Joan’s suffering, both before and during the brutal attack, is a stark contrast to the emotional numbness and detachment displayed by the girls. The way Joan’s life and death are framed throughout the novel forces readers to confront the ethics of victimhood and the nature of violence in contemporary society.

Jayde Spencer

Jayde Spencer, initially referred to as Girl D, is a character whose life is destroyed by the fallout from the crime. Though she had no direct involvement in Joan’s murder, Jayde is arrested and implicated due to her association with Dolly and her family’s questionable reputation.

Jayde’s character serves as a critique of the media and justice system, highlighting how easily reputations can be destroyed based on assumptions and proximity to scandal. Her story reflects the collateral damage of the crime, as she becomes a scapegoat for a situation she had no control over.

Jayde’s narrative sheds light on the systemic failures that often punish the innocent, particularly those from marginalized backgrounds.

Mad Bob

Mad Bob is a local eccentric in Crow-on-Sea, and while he is not directly involved in the murder, his presence adds depth to the town’s character. Bob represents the myths and stories that the town holds onto, contributing to the larger theme of isolation and alienation.

His role in the novel serves to amplify the sense of a decaying social environment where both the town and its inhabitants are disconnected from reality. Through Mad Bob, the novel explores themes of nostalgia, social decline, and the need for a scapegoat, all of which tie back to the tragedy that unfolds.

His eccentricity contrasts with the darkness of the girls’ actions, making him a poignant figure in the novel’s commentary on societal decay.

Themes

Influence and Power in Shaping Individual Morality

One of the central themes of Penance is how power dynamics within a small group can shape an individual’s actions and moral compass. Through the characters of Angelica, Violet, and Dolly, the narrative explores how different personalities interact and influence each other in toxic ways.

Angelica, with her background of wealth and influence, emerges as the mastermind, drawing others into her orbit with manipulative tactics. Violet, the more introspective and anxious character, finds herself constantly swayed by the group’s increasingly delusional views and violent tendencies.

Dolly, on the other hand, plays the role of the ringleader, holding a magnetic yet sinister pull over the others. This theme probes the psychological and social pressures that can make an otherwise passive person become complicit in immoral acts.

It’s a deep dive into how vulnerability, longing for belonging, and an external force like a charismatic leader can push people towards actions they might not otherwise take.

Class, Identity, and Social Perception in Shaping Justice

Another critical theme in Penance is the intersection of class, identity, and social perception, particularly as it relates to justice. The book reveals how systemic biases—rooted in media sensationalism, class, and family reputation—can lead to false accusations and tarnished reputations.

Jayde Spencer, mistakenly implicated in the murder, becomes a victim of this very system, representing how social class can skew justice. Her background, coupled with her connection to the other girls, makes her a convenient scapegoat in the eyes of the police and the public.

The narrative criticizes how certain social groups, especially young women from marginalized backgrounds, are quick to be vilified when tragedy strikes. All while those with power and influence often escape the full weight of their responsibility.

This exploration uncovers the deep flaws within systems of justice, showing how public opinion, driven by sensationalist narratives, can ruin lives without proper cause or evidence.

Escalating Descent into Fantasy and Violence

The theme of reality disintegration is explored through the girls’ descent into violence and delusion. Over the course of the book, particularly through sections like Halloween and The Witch Hammer, the narrative illustrates how the girls’ obsession with violence, macabre rituals, and online folklore becomes increasingly detached from reality.

This deterioration of the boundary between fantasy and actual behavior is evident in their constructed mythologies about Joan. They start to believe Joan is a ‘witch’ deserving of punishment.

Their escalating violent tendencies are not just acts of physical harm, but a manifestation of their internal chaos and the disconnect they feel from a world that seems too harsh to understand.

The book critiques the allure of escapism through violence and online subcultures, shedding light on how these influences, especially in young minds, can distort reality and justify actions that would otherwise be unimaginable.

The Spring Equinox, with its themes of rebirth and ritualistic significance, marks the final stage in their twisted path toward the horrific crime they commit. It represents the culmination of their break from reality.

Tragedy and the Ethics of True Crime Culture

Finally, Penance delves into the dark world of true crime culture and the ethical considerations surrounding the consumption of tragedy. The final section, Aftermath, takes a critical stance on how tragic events like Joan’s murder are transformed into entertainment and spectacle by the media and public.

The book doesn’t shy away from questioning the role of readers and audiences in perpetuating this culture. It urges them to reflect on their complicity in consuming and sensationalizing the pain of others.

It calls attention to the exploitation of victimhood for entertainment value. The book critiques how the real-life grief and suffering of families and communities are often overshadowed by the thirst for voyeuristic narratives.

The ethical implications of storytelling, particularly in the context of true crime, are laid bare. It forces the reader to confront the often exploitative nature of their own engagement with such narratives.