People Like Us by Jason Mott Summary, Characters and Themes

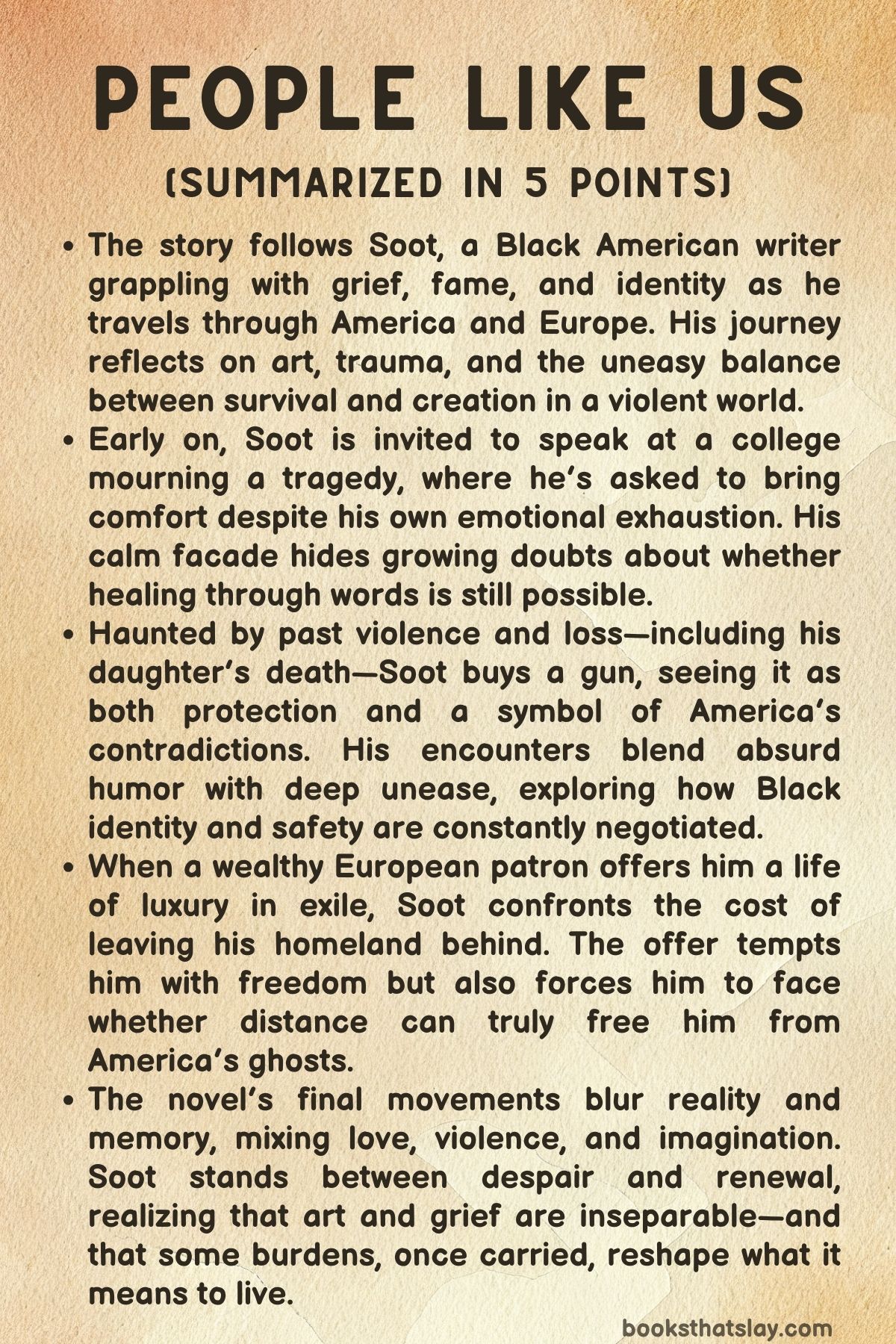

People Like Us by Jason Mott is a bold and reflective novel that blurs the boundaries between memory, imagination, and truth. The story follows Soot, a Black American writer who journeys across America and Europe while wrestling with grief, fame, and identity.

Through fragmented storytelling, dark humor, and surreal encounters, Mott explores the weight of history, the lingering trauma of racial violence, and the tension between escape and belonging. It is a deeply introspective narrative about what it means to live, to remember, and to carry the ghosts of a nation — a meditation on art, loss, and the stories that refuse to die.

Summary

The novel begins with Soot, a middle-aged Black writer, traveling to Minnesota to deliver a lecture at a college mourning students lost in a recent tragedy. As he journeys through a freezing storm, he contemplates aging, race, and his career built around America’s grief.

His escort, desperate for reassurance, asks if things will ever be okay. Soot answers gently, though even he seems unsure.

Amid the howling wind, he senses a strange presence — a voice or song in the snow — before disappearing into the storm.

The narrative shifts backward to the “Summer of the Great Get Back,” a time of apparent social progress when protests filled the streets and optimism bloomed. Yet as autumn arrived, that momentum faded, leaving disillusionment and the return of old systems.

Soot, both observer and participant, recounts the absurdity of hope and despair intertwined in American life. He admits he once left the country after a disturbing encounter in Los Angeles — an incident that continues to haunt him.

Years earlier, during his brief Hollywood fame, Soot was attacked in an alley by John J. Remus, a powerful, older Black man who assaulted him in a bizarre act that blended violence and conversation.

Remus examined Soot’s teeth like a horse trader, praised their “quality,” and calmly announced his intent to kill him. The story cuts away before revealing what happened next, creating a lingering mystery.

On a later flight to Europe, Soot recounts the incident to a woman named Stephanie, claiming to be another writer — first Ta-Nehisi Coates, then Walter Mosley — as a form of protection. This habit of borrowing other names reflects his fractured sense of identity.

He remains haunted by Remus’s words and unsure whether the threat was real or imagined.

Arriving in Toronto, Soot visits his ex-wife, Tasha. They share the unbearable grief of losing their daughter, Mia.

He insists he can time travel — literally — to revisit moments from their family’s life, reliving their happiness and confirming they were blameless in her death. Tasha listens, torn between compassion and concern for his sanity.

She tells him Mia is gone and that he must let go. Soot, unable to face this truth, leaves in silence, his grief as heavy as the air around him.

The story circles back to his rise to fame. Soot wins “The Big One” — the National Book Award — for a novel born of tragedy.

His celebration is extravagant, yet beneath the glamour he feels hollow. His agent, Sharon, tells him a powerful European benefactor known as Frenchie wants to host him abroad, promising freedom and wealth.

Europe, she claims, is a place where Black writers are celebrated, not consumed. Amid the noise of fireworks, Sharon’s voice shifts into Remus’s, warning that “he’s going to find you.” Soot, unsure if he’s hallucinating, feels the world tilt between memory and madness.

In the next phase, Soot buys a Colt . 45 from a pawnshop in North Carolina before leaving for Europe.

The purchase scene is laced with dark humor — the gun represents both freedom and fear, mirroring America’s obsession with weapons as symbols of control. The shop owner’s casual racism underscores how violence and liberty are entangled in American identity.

With the gun hidden in his luggage, Soot travels to Italy, seeking safety that remains elusive.

In Milan, he meets The Goon, a massive Scottish chauffeur who drives him through the city in an ancient car. The Goon insists Soot discard his phone and leave his past behind, guiding him toward a vast villa owned by Frenchie.

The mansion is filled with priceless relics of Black artistry — Baldwin’s notes, Hughes’s manuscripts, Simone’s secret recordings. Frenchie, flamboyant and philosophical, declares that America is decaying and that artists like Soot must stay in Europe to preserve the spirit of what once was.

He offers Soot immense wealth to never return to America, claiming it as both sanctuary and rebirth. Soot realizes that many before him accepted similar deals, turning their exile into art.

Torn between belonging and betrayal, he agrees, knowing that safety may cost him his soul.

Later, Soot is stabbed in Italy and wakes up in a luxurious hospital owned by Frenchie. His friends Dylan — once his imaginary childhood companion — and The Goon care for him.

A note from Remus reading “Keep brushing! ” is found at the scene, signaling that the old threat has followed him across the ocean.

Dylan, now Frenchie’s assistant, reveals his own trauma, suffering from episodes that return him mentally to Baltimore. Frenchie urges Soot to stay in Europe and continue “The Big Score.” Exhausted, Soot drifts between dreams and dread.

One day, he encounters Kelli, a woman from his past who once gave him comfort during his depression. She reveals she left America after too many funerals for children killed by gun violence.

Death, she says, “is better in Europe. ” They reconnect and travel to Paris with Dylan and The Goon, forming a strange, surrogate family.

Along the way, Dylan edits a massive montage of apocalypse films while the others grapple with their pasts. When they stop to shoot Soot’s gun in the hills, the sound unleashes waves of buried memory — funerals, shootings, losses — echoing the collective trauma of Black life in America.

In Paris, they settle at Frenchie’s mansion, withdrawing from the world. Dylan falls into a mysterious coma, reliving a school shooting in his dreams.

Meanwhile, Soot performs readings about his daughter, recounting her birth and death, and mourning the way America consumes its own children. During one event, a student simply thanks him “for being weird,” breaking his emotional walls.

His writing becomes a means to survive what logic cannot heal.

Months pass. The group lives in isolation, their new home becoming a self-made continent.

Then, without warning, Remus reappears, intent on fulfilling his promise. In a chaotic scuffle, Soot’s gun fires and accidentally kills Dylan.

Remus leaves, remarking that they brought America’s violence with them — that it can never be escaped. The tragedy shatters what little peace they found.

Overcome with guilt, Soot runs through Paris with the gun and tries to drop it into the Seine, but it refuses to fall, hanging in the air like an unfinished act. This surreal image captures the novel’s central idea: America’s violence, once internalized, can never truly be let go.

The closing chapters find Soot reflecting on suicide, despair, and survival. He recalls the many times he thought of ending his life — as a teenager with his father’s shotgun, as a man with an HK.45 in Switzerland — but always pulled back. His final encounter is with a teenage American girl in Paris who fears returning home because she might die in a school shooting.

Together, they share a moment of recognition — both haunted by a country that devours its own people. Soot promises to tell her a story, because words, even when powerless, remain the only way to make sense of the pain.

The novel ends with that promise — a story within a story — a fragile act of defiance against forgetting.

Characters

Soot

Soot, the central narrator of People Like Us, embodies both the voice and wound of contemporary America. A middle-aged Black writer, he navigates through the overlapping terrains of memory, race, trauma, and art.

His name—Soot—evokes residue, something left behind after fire, an apt metaphor for his existence marked by loss and persistence. He is introspective and self-aware, aware of his symbolic weight as a “Black voice,” yet burdened by the constant expectation to translate pain into wisdom.

His journey oscillates between realism and surrealism: from giving grief-soaked talks in Minnesota to encountering ghosts of violence and fame in Europe. He is haunted by the death of his daughter, Mia, and the dissolution of his marriage with Tasha, both of which deepen his obsession with time and the idea of revisiting the past.

His purchase of a gun and his encounters with Remus reveal how fear and survival have become inseparable for him. Soot’s recurring reflections on America’s violence, its cyclical grief, and his own guilt for leaving it, make him a deeply conflicted exile—caught between wanting safety and needing to bear witness.

His eventual confrontation with Remus, ending in Dylan’s death, symbolizes the futility of escaping America’s violence: even in Europe, he cannot escape its shadow. Soot is at once artist, mourner, and fugitive—a man writing to survive his own story.

John J. Remus

John J. Remus is a spectral figure who embodies menace, trauma, and accountability.

His first appearance as an attacker in a Los Angeles alley marks him as both literal threat and psychological manifestation. The bizarre nature of his assault—examining Soot’s teeth and promising to kill him—suggests he is less a man than a projection of Soot’s internalized fear, perhaps even the embodiment of America’s violence against Black bodies.

Yet Remus’s later reappearances blur this line between metaphor and reality. He taunts, follows, and finally re-emerges to deliver the fatal confrontation that costs Dylan’s life.

Remus is articulate, almost philosophical, treating murder as ritual and inevitability. He seems to move through time and space with ease, reinforcing his role as the ghost of history itself—an ever-returning presence of racial trauma that no continent can contain.

His casual apology after killing Dylan reinforces his paradoxical nature: a killer aware of tragedy, violence wrapped in weary civility. Remus is the novel’s haunting conscience, the reminder that one cannot flee the violence woven into one’s origins.

Tasha

Tasha, Soot’s ex-wife, is a figure of quiet resilience and emotional truth. She represents the grounded counterpart to Soot’s drifting and self-destructive introspection.

Defined largely through moments of shared grief and distance, she carries the unbearable pain of losing their daughter, Mia, while still trying to live in the present. When Soot insists he can time-travel to relive their past, she listens patiently before reminding him that Mia is gone and that clinging to the impossible will destroy him.

Her empathy is clear, but so is her exhaustion—she has accepted the finality of loss that Soot cannot. Tasha’s character reveals the limits of love when grief becomes boundless.

She is the one who understands that healing requires release, not obsession. Through her, the story explores emotional endurance: how one continues in the aftermath of unimaginable loss without the luxury of retreating into imagination or madness.

Mia

Mia, Soot and Tasha’s daughter, functions as both memory and spirit within People Like Us. Though deceased, her presence infuses the narrative with tenderness and longing.

In Soot’s recollections, she is “a born fixer,” symbolizing innocence, hope, and the tragic futility of trying to mend what cannot be fixed. When she appears in visions—sometimes as a child, sometimes as a teenager in the dress she died in—she becomes the voice of emotional truth.

Her conversation with Soot about sadness and feeling too much encapsulates the book’s central grief: that those who feel deeply are often consumed by the pain of others. Mia’s existence transcends death; she lives within Soot’s voice, within the act of storytelling itself.

Her memory is both comfort and curse, a reminder of love’s permanence and the impossibility of undoing tragedy. She embodies the ache of a parent’s guilt and the lingering question of whether art can redeem grief.

Dylan (The Kid)

Dylan, once Soot’s imaginary friend and later a real companion in Europe, represents the blurred boundaries between imagination and reality. As “The Kid,” he was a manifestation of Soot’s loneliness and creative turmoil; as Dylan, he returns as a mirror—part protégé, part ghost, part son.

His editing of apocalypse films, his blackouts, and his panic attacks reveal his own internalized trauma, echoing the collective pain of a generation shaped by violence and fear. Dylan’s eventual death at the hands of Remus—an accident born from chaos—solidifies him as the ultimate victim of transposed violence.

His existence bridges dream and reality, showing how grief and imagination intertwine until they are indistinguishable. Dylan’s childlike vulnerability and artistic sensibility make his death particularly devastating, underscoring the novel’s message that even in exile, one cannot escape the reach of American violence.

The Goon

The Goon, the large Scottish chauffeur, provides a blend of comic relief, philosophical grounding, and emotional stability. Despite his intimidating size, he exudes gentleness and loyalty, serving as a guardian figure to Soot.

His dialogue often touches on belonging, identity, and fear, allowing for some of the novel’s most meditative exchanges. He bridges cultures and languages, embodying the hybrid existence of exile—someone displaced but still searching for home.

His fascination with guns and America’s mythology of freedom contrasts with his calm demeanor, highlighting how violence and curiosity coexist even in those far removed from its epicenter. The Goon’s quiet compassion makes him one of the few stabilizing presences in Soot’s chaotic journey, yet his helplessness during Dylan’s death shows the limits of protection in a world saturated by inherited violence.

Kelli

Kelli, the undertaker and Soot’s former lover, is both life and death incarnate. Her profession connects her to mortality, yet her personality radiates humor, sensuality, and defiance.

Having fled America because she was overwhelmed by burying children killed by gun violence, she represents the moral exhaustion of a society accustomed to tragedy. When she reenters Soot’s life in Italy, their reunion carries the weight of fate and unfinished emotion.

Her uncanny ability to hear Soot’s thoughts reinforces her symbolic nature—she is the reader of his soul, the one who listens when he cannot even hear himself. Through Kelli, the novel examines how intimacy can exist within trauma, and how love can re-emerge, however fleetingly, amid ruin.

Her acceptance of death and ability to move forward contrasts with Soot’s fixation on the past, making her an emblem of endurance and rebirth.

Frenchie

Frenchie, the eccentric billionaire patron, embodies the seductive face of exile. He offers Soot the chance to escape America’s brutality in exchange for artistic servitude—wealth and safety for silence and distance.

His mansion, filled with relics of Black genius, represents both sanctuary and mausoleum. Frenchie’s philosophy—that America is collapsing and that Black artists must preserve its memory from afar—carries both truth and danger.

He romanticizes the expatriate ideal, but beneath the opulence lies control and erasure. His “Big Score” is an illusion of liberation that perpetuates the same systems of power it pretends to transcend.

Frenchie is thus a paradox: savior and jailer, patron and colonizer of art. His charm conceals complicity, making him the embodiment of Europe’s historical role as both refuge and voyeur of Black suffering.

Themes

Grief and the Inescapability of Loss

In People Like Us, grief is not a singular event but an enduring state of existence that defines Soot’s emotional and spiritual world. His daughter’s death creates a fracture in time and self that he cannot bridge, no matter how far he travels or how many times he revisits memory.

The novel presents grief as an omnipresent companion—shaping Soot’s speech, his hallucinations, his relationships, and even his art. His attempts to convince Tasha that he can travel through time reveal a desperate effort to repair the irreparable, to impose logic on tragedy.

But what haunts him most is not just the loss of his daughter; it is the realization that no story, no success, and no belief in progress can neutralize the permanence of death. His grief is interwoven with guilt, not because of any fault, but because survival itself feels like betrayal.

In this emotional terrain, grief becomes both burden and compass—it drives his creativity but also corrodes his sanity. Through Soot’s eyes, mourning transforms into a form of haunting; his conversations with Mia, whether real or imagined, illustrate that memory can resurrect as much as it destroys.

The novel portrays grief as an inheritance passed through generations of Black experience—personal loss merging with historical trauma—suggesting that sorrow is as much a legacy of America as it is of the individual heart.

Racial Identity and the Burden of Representation

The narrative constantly places Soot in spaces where his Blackness is simultaneously sought after and suffocating. He is invited to speak “to grief,” to embody healing for others, even when he cannot manage his own pain.

His identity as a Black writer becomes a commodity, an expectation, and at times a trap. Through the scenes at the memorial dinner, the airport, and later in Europe, Jason Mott captures how society consumes Black art and pain while rarely acknowledging the humanity beneath it.

Soot’s exchanges with white academics and with his European patrons expose the paradox of representation: he must perform authenticity while hiding exhaustion. The weight of being both symbol and man isolates him.

Even his success, crowned by “The Big One,” feels hollow, as it rewards his suffering rather than his vision. Abroad, he becomes an exhibit in Frenchie’s fantasy of enlightened exile—a curated version of Black genius sanitized for wealthy consumption.

Yet, despite all this, Soot clings to a fragile sense of pride. His Blackness, though exploited, remains his source of power and connection; it binds him to others like Dylan and The Goon, whose own struggles reflect the generational ache of identity under pressure.

The novel exposes how racial identity in America and beyond becomes a constant negotiation between survival, authenticity, and fatigue.

The Violence of America and the Illusion of Safety

Guns pulse through People Like Us as recurring symbols of fear, power, and delusion. Soot’s purchase of the Colt .

45 in North Carolina is not an act of aggression but a ritual of protection in a nation where Black bodies are perpetually vulnerable. The gun offers comfort—a material promise that he can control his own death if not his life.

Yet, as the story unfolds, the weapon transforms from safeguard to curse. Its presence in Europe, culminating in Dylan’s accidental death, demonstrates that America’s violence is portable; it travels with its people like a contagion.

Even in supposed exile, Soot cannot escape the psychic residue of a country obsessed with guns and haunted by mass shootings. The “active shooter” training video and the flashbacks to his daughter’s death underscore how normalized brutality has become.

The final image of the gun refusing to fall into the Seine serves as an emblem of America’s unrelenting grip on its citizens—the inability to discard the culture of violence even when oceans away. Through this, Mott exposes safety as an illusion sustained by denial, revealing that true danger lies not in weapons alone but in the ideologies that justify them.

Exile, Displacement, and the Search for Home

Throughout the novel, Soot’s journey across borders reflects an existential homelessness. Whether in Minnesota, North Carolina, or Paris, he remains untethered, a wanderer seeking a place untouched by grief or racism.

Frenchie’s offer of eternal residence in Europe masquerades as liberation, yet it only deepens his alienation. To accept it is to become a living monument—preserved, admired, but disconnected from the soil that made him.

This exile mirrors the historical experiences of Black artists who fled America in search of dignity and freedom, only to find themselves trapped between admiration and erasure. Soot’s encounters with Dylan, The Goon, and Kelli reveal that displacement is both physical and psychological.

They too are refugees from violence, seeking meaning in foreign landscapes that promise peace but deliver loneliness. The imagined “Other Continent” they create becomes a metaphor for the liminal space of trauma survivors—neither here nor there, suspended between memory and possibility.

Home, in Mott’s vision, is not a place but a condition of belonging that remains perpetually out of reach.

Art, Storytelling, and the Burden of Meaning

Art in People Like Us emerges as both salvation and affliction. Soot’s entire life is built upon storytelling, yet his narratives continually fail to protect him from reality.

His fame is born from trauma, and his success depends on the perpetual retelling of pain. Mott critiques how the literary world commodifies suffering, turning it into currency for empathy and acclaim.

Soot’s encounters with Frenchie’s relics—Baldwin’s notebook, Hughes’s manuscript, Simone’s recording—represent the sacred lineage of Black art but also its imprisonment within elite archives. These artifacts, preserved behind glass, symbolize how even revolutionary voices can be silenced by reverence.

The novel also interrogates storytelling as self-preservation: Soot lies about his identity, invents pasts, and uses words as armor against annihilation. Yet, despite deception and distortion, language remains his last refuge.

When he promises the young girl by the Seine to tell her a story, it becomes an act of reclamation—a belief that words, however fragile, still matter. Mott ultimately suggests that storytelling cannot fix the world, but it can bear witness to its wounds, ensuring that the voices of “people like us” are never fully erased.