People of Means Summary, Characters and Themes

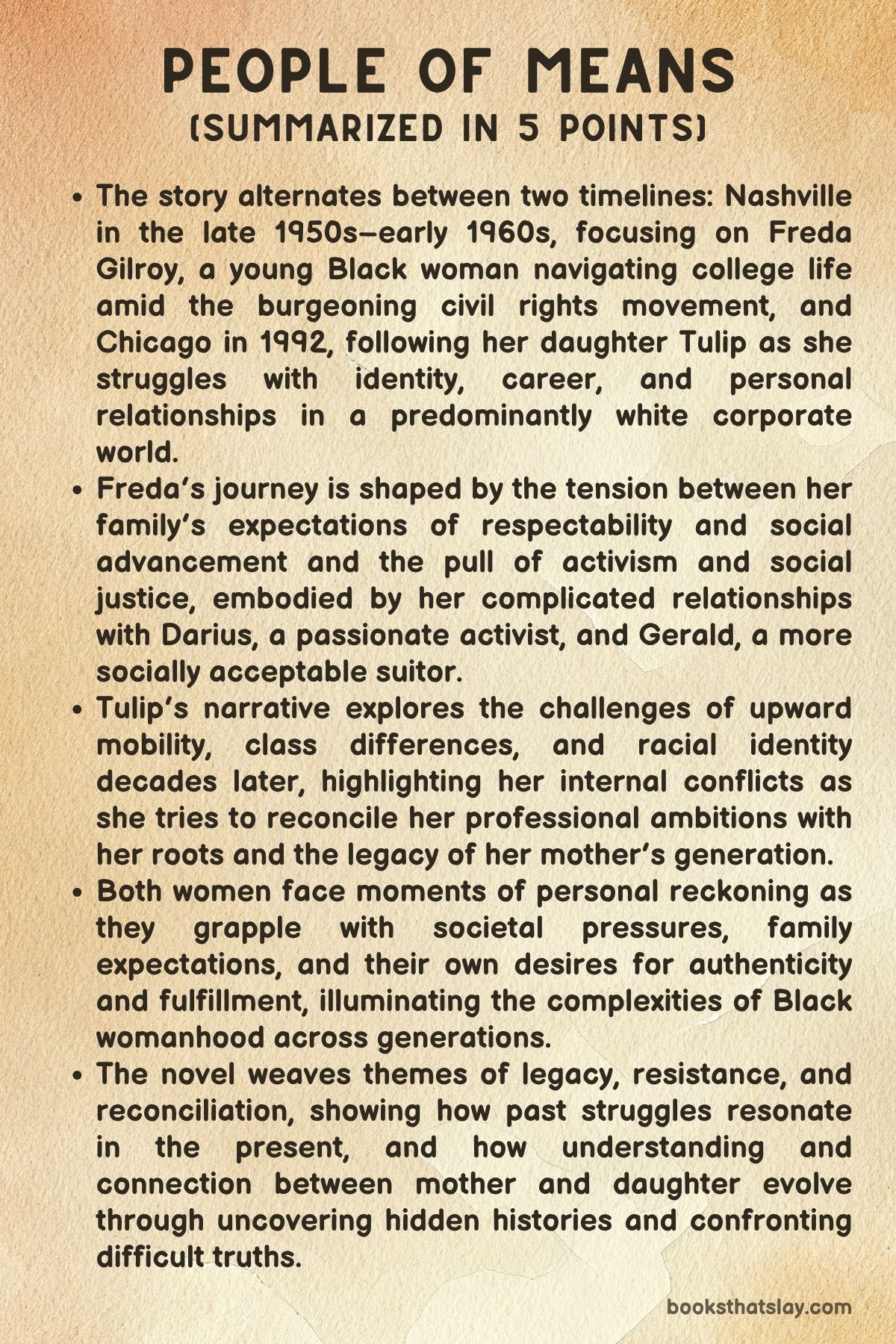

People of Means by Nancy Johnson is a compelling exploration of identity, family, and personal growth set against the backdrop of a racially divided America during the 1960s. The story follows Freda Gilroy, a young Black woman navigating the complexities of college life at Fisk University.

Amid academic pursuits, personal relationships, and burgeoning awareness of the Civil Rights Movement, Freda must reconcile her own ambitions with the weight of her family’s expectations. Through the trials of friendship, love, and activism, Freda’s journey is a deep reflection on the tension between individual desires and societal pressures, particularly in a time of great social change.

Summary

Freda Gilroy’s journey begins as she steps onto the campus of Fisk University, embarking on what she hopes will be a transformative educational experience. She is one of 78 freshmen women, and her arrival is marked by a mix of excitement and fear, particularly under the imposing authority of Mother Gaines, who sets strict guidelines for the students’ conduct.

Freda’s father has sent her to Fisk not just for an education, but as a legacy, a continuation of a family tradition that links them to the proud history of Black excellence in education. For Freda, Fisk represents more than a school—it is the embodiment of the potential for Black liberation, a place where the doors of opportunity can be unlocked through knowledge.

Despite the intimidating presence of Mother Gaines, Freda soon finds a sense of camaraderie with her roommates, Evaline and Cora. Evaline, bold and rebellious, offers a stark contrast to the more reserved Cora, who is pragmatic and grounded.

These relationships become crucial to Freda’s development, pushing her to expand beyond the boundaries of her upbringing while offering a source of support in this new and unfamiliar world. As the trio navigates university life, Freda grows, her ambitions taking root, though she still remains tethered to the expectations of her family, particularly regarding her future.

Though Freda is at Fisk to study mathematics, she finds herself distracted by Darius Moore, a philosophy major whose talents and presence intrigue her. They first meet when Freda hears Darius playing his saxophone at Fisk Memorial Chapel.

Their connection is immediate, but it is complicated by Freda’s upbringing. Her parents have high hopes for her, and they encourage her to pursue an appropriate marriage with Gerald Vance, a medical student at Meharry Medical College, someone who fits the mold of a successful Black man in their community.

Freda’s encounter with Darius at the state fair marks a pivotal moment in her life. It is there that she faces the cruel realities of segregation, experiencing firsthand the humiliation of racial inequality as she encounters segregated facilities.

This event shakes Freda deeply, challenging the comfortable worldview she has grown up with. She finds herself grappling with the realities of racism in the South, a stark contrast to the privileged position she once thought she occupied due to her family’s legacy.

As Freda struggles with her feelings for Darius, she also continues to feel the weight of her family’s expectations bearing down on her. Her relationship with Darius, who comes from a modest background, forces Freda to confront her perceptions of race and class.

She begins to question whether following the path her parents have envisioned for her is truly the way to fulfillment, or if forging her own path might be the only way to achieve real happiness.

The story deepens further as Freda’s college life becomes more entwined with the growing Civil Rights Movement. Her friend Evaline brings her attention to Gerald Vance, whose academic success becomes a topic of conversation among the students.

While Freda has no personal connection to Gerald, his success seems to be shared by association, reflecting the complicated web of relationships at Fisk. Freda’s personal life becomes more complicated as her involvement with Darius deepens.

Darius, a passionate activist, encourages Freda to step away from her intellectual pursuits and embrace a more active role in the Civil Rights Movement. Darius’s radicalism challenges Freda’s more cautious and academic approach, leaving her torn between her desire for stability and the compelling call to action that Darius represents.

The situation escalates when Freda witnesses a sit-in protest at McLellan’s, a pivotal event that forces her to confront the injustices of segregation directly. She feels torn between the intellectual path she has pursued and the urgent need to act in the face of systemic racial inequality.

Freda’s discomfort with the activism at first is clear, yet she cannot deny the courage of those involved in the protests, especially Darius, who takes a leading role in organizing them. The sit-ins become a symbol of the larger struggle for racial equality, and Freda’s internal conflict intensifies as she grapples with the complexities of the fight for justice.

Freda’s journey is further complicated by her recovery from a mild traumatic brain injury sustained during one of the violent protests. The emotional toll of the protests and the violence that Black activists faced at the hands of white mobs deepen Freda’s awareness of the brutal realities of racism.

Her recovery is not just physical—it is emotional and intellectual. She begins to question the place of her family’s expectations in her life and whether her intellectual pursuits can truly bring about the kind of change she now believes is necessary.

Despite her concussion, Freda finds herself visiting Darius in jail, where she sees his unyielding commitment to the movement. Their conversation highlights the stark differences in their worldviews: Darius prioritizes the movement’s long-term strategy, whereas Freda is focused on immediate concerns and personal safety.

This encounter forces Freda to reckon with the sacrifices that the Civil Rights Movement demands, and she begins to see the world in a more critical, yet hopeful, light.

Freda’s relationship with Gerald deteriorates as his disinterest in the Civil Rights Movement becomes more apparent. Freda, now deeply involved in activism, begins to see the divide between them as insurmountable.

The ideological and emotional distance between them grows, and Freda starts to question her future with him. She attends a meeting led by Darius, where she begins to volunteer for the movement, using her skills to support the cause.

Her involvement in activism strengthens as she connects with the larger struggle for racial justice.

Freda’s self-discovery reaches a climax as she confronts the tensions in her personal life and political beliefs. Her relationships with Gerald, Darius, and her friends reflect the larger social and political changes sweeping the nation.

Freda’s journey is one of finding balance between family expectations, personal desires, and the call to action in the fight for justice. The novel ends with Freda standing at the crossroads of her life, her path shaped by the legacy of her family and the evolving reality of her own identity in a racially divided America.

Characters

Freda Gilroy

Freda Gilroy, the protagonist of People of Means, is a young woman embarking on her academic journey at Fisk University, where she is shaped by both her personal ambitions and the weight of her family’s expectations. As a Black woman in the South during the Civil Rights Movement, Freda’s experience is marked by an evolving sense of self.

She is initially introduced as someone who values her academic success, especially her pursuit of mathematics, and is determined to honor her family’s legacy of excellence. Freda is intelligent, ambitious, and well-meaning, but she is also deeply rooted in the ideals and expectations of her parents.

As the story progresses, Freda is forced to confront the conflict between her intellectual path and the demands of social activism, particularly through her interactions with Darius Moore, a civil rights activist whose passion for justice pulls Freda out of her comfort zone. Her internal struggles mirror the broader societal issues of race, class, and identity, as she grapples with her desire for personal success and her responsibility to the greater cause of equality.

Ultimately, Freda’s journey is one of self-discovery, where her academic and personal lives converge, and she must reconcile her family’s values with her own evolving understanding of race, activism, and love.

Darius Moore

Darius Moore, a philosophy major at Fisk University, plays a pivotal role in Freda’s transformation throughout People of Means. As a passionate advocate for civil rights, Darius represents the active, radical side of the movement.

His political activism contrasts sharply with Freda’s more cautious and academic approach, and their relationship highlights the tension between personal aspirations and the urgent need for action against racial injustice. Darius’s commitment to the movement is unwavering, even in the face of personal danger, as seen when he refuses to pay bail after being arrested.

His leadership in protests, particularly his role in organizing sit-ins and speaking at rallies, challenges Freda’s understanding of race, class, and her place in society. While Freda initially views him with some skepticism, his dedication to social change slowly transforms her perspective.

Darius embodies the courage to act, pushing Freda to question the balance between intellectual pursuits and direct involvement in the fight for racial equality. Despite the deep personal connection between them, Freda’s reluctance to fully embrace the movement is evident, making Darius a key figure in her internal struggle and eventual awakening.

Gerald Vance

Gerald Vance is another important figure in Freda’s life, representing the more traditional, established path that Freda’s parents envision for her. A medical student at Meharry Medical College, Gerald is the ideal suitor according to Freda’s family.

He is intelligent, successful, and seemingly a safe choice for a future partner, offering stability and respectability. However, Gerald’s views are in direct contrast to Freda’s growing awareness of the Civil Rights Movement.

While Freda is drawn to Darius’s activism, Gerald remains detached from the political struggles that define the era. His overprotectiveness towards Freda, especially after her involvement in the protests, further highlights their differing priorities.

Gerald’s refusal to engage with the larger societal issues that are shaping Freda’s life creates a growing rift between them, forcing Freda to reconsider their relationship. Despite his genuine care for Freda, Gerald represents the traditional, conservative values that Freda increasingly finds at odds with her emerging sense of purpose.

Evaline

Evaline, Freda’s roommate at Fisk, plays an essential role in the development of Freda’s character. While Evaline is bold and mischievous, offering a stark contrast to the more reserved and sensible Cora, her presence in Freda’s life is one of both challenge and support.

Evaline’s free-spirited nature pushes Freda to step outside her comfort zone, encouraging her to embrace the unfamiliar and to explore the complexities of her new environment. While Evaline’s rebelliousness can sometimes be at odds with Freda’s more cautious approach, their friendship deepens over time.

Evaline’s role in Freda’s life is crucial during moments of personal doubt, especially when Freda is torn between the intellectual path laid out by her parents and the emotional pull of activism. Despite the differences in their personalities, Evaline’s friendship provides Freda with the grounding and courage she needs to navigate the turbulence of her college years.

Cora

Cora, Freda’s other roommate at Fisk, offers a more sensible and grounded perspective compared to Evaline’s impulsive nature. Cora’s role in Freda’s life is one of emotional support, as she helps balance Freda’s more intense relationships with the quieter, introspective moments that allow Freda to reflect on her evolving identity.

Cora’s financial struggles and the burdens she faces due to her parents’ involvement in an underfunded education system serve as a reminder of the systemic issues that Freda is beginning to understand. Cora’s more practical approach to life contrasts with Freda’s lofty ideals, but she remains a steady, understanding friend throughout Freda’s journey.

While Cora does not engage as deeply with the political activism surrounding them, her friendship offers Freda a sense of stability as she confronts the challenges of her personal and academic life.

Key

Key is a pivotal character who struggles with the emotional and societal repercussions of his past criminal record. Recently released from jail, he feels the weight of societal prejudices that continue to haunt him despite his efforts to move forward.

His relationship with his girlfriend, Tulip, is marked by a complex mix of love, guilt, and the external pressures that stem from his past. Although Key is committed to personal growth, he remains deeply affected by the stigma surrounding his criminal record, which makes it difficult for him to see himself outside of the labels imposed upon him.

His struggle for redemption and his efforts to rebuild his life are complicated by his ongoing feelings of alienation from his family, who pity him, and his relationship with Tulip, who sees beyond his past. Key’s internal conflict reflects broader themes of identity, societal judgment, and the difficulty of escaping one’s past in a world that refuses to let go of it.

Tulip

Tulip is a strong and principled character whose journey is deeply intertwined with both her personal and political growth. As an activist committed to social justice, she is dedicated to helping marginalized communities, despite the personal sacrifices it requires.

Her decision to quit her high-profile PR job after leading a protest marks a significant turning point in her life, as she shifts from the corporate world to grassroots activism. Tulip’s relationship with Key is central to her personal narrative, as she grapples with the complexities of their connection.

While she loves him, she also recognizes the systemic racism that has shaped his life and struggles to balance her commitment to social justice with her love for him. Tulip’s unwavering dedication to activism and her ability to navigate the contradictions in her own life make her a resilient and dynamic character, driven by the desire to make a meaningful impact on the world around her.

Themes

Legacy and Family Expectations

The concept of legacy plays a significant role in shaping Freda’s journey at Fisk University. From the very beginning, Freda’s father emphasizes the importance of continuing the family’s connection to the institution, encouraging her to carry forward the legacy of excellence that her parents deeply value.

This expectation is not just about academic success but is intertwined with the belief that education is the key to liberation for Black people. However, as Freda navigates her time at Fisk, she begins to experience the tension between honoring this legacy and pursuing her own personal aspirations.

The weight of familial expectations weighs heavily on her, particularly when it comes to decisions about marriage and career. Her parents envision a traditional path for her—one that is in line with their values—but Freda, influenced by the challenges she faces and the relationships she forms, begins to question whether following their blueprint will lead to true fulfillment.

The theme of legacy in this narrative reveals the internal conflict between honoring the past and carving out an independent identity.

Identity and Self-Discovery

Freda’s time at Fisk University serves as a crucible for her identity formation. As she adjusts to university life, she is pushed beyond the boundaries of her upbringing and forced to confront the complexities of race, class, and personal desire.

Her relationships with her roommates, Evaline and Cora, serve as a mirror reflecting different aspects of her personality, from her academic ambition to her budding sense of independence. Through these friendships, Freda gradually comes to understand the multifaceted nature of her own identity.

She realizes that her desire for success in mathematics and a traditional lifestyle must be balanced with a growing sense of freedom that challenges the constraints of her upbringing. Moreover, her attraction to Darius, a philosophy major and civil rights activist, sparks a deeper questioning of her values.

Freda’s internal struggle between following her family’s prescribed path and seeking her own truth becomes the central journey of self-discovery. The theme of identity in the narrative explores the evolving process of recognizing one’s individuality amidst societal pressures and familial expectations.

Race and Racial Identity

The theme of race and racial identity is woven throughout Freda’s story, particularly in her experiences navigating a segregated South. Her initial experiences at Fisk are colored by her upbringing in a world that values education as a means of achieving freedom and upward mobility.

However, as Freda interacts more with her peers and the broader community, she is forced to confront the brutal realities of racial inequality. Her discomfort during a visit to the state fair, where she faces the indignities of segregated facilities, marks a pivotal moment in her awareness of the systemic racism that defines the world around her.

This racial divide becomes even more apparent as Freda develops a relationship with Darius, a man from a more modest background who is actively involved in the Civil Rights Movement. The contrast between Freda’s sheltered upbringing and the harsh realities faced by people like Darius challenges her perceptions of race, privilege, and her own role in society.

As Freda becomes more involved in activism, she grapples with the complexities of being both a Black woman in a segregated society and a student trying to maintain her academic focus. The theme of race and racial identity in the novel examines the shifting perspectives of a young woman coming to terms with the inequities of the world and her place in the struggle for justice.

Societal Expectations and Personal Freedom

Freda’s growing involvement in the Civil Rights Movement serves as the backdrop for a deeper exploration of societal expectations and personal freedom. While her parents have a clear vision for her future—focused on marriage to a suitable partner and academic achievement—Freda finds herself pulled in different directions as she becomes more aware of the broader social issues at play.

The divide between her intellectual pursuits and the activism led by figures like Darius creates an internal conflict in Freda. Her initial hesitation to join the protests is based on a fear of losing the security and stability that education and marriage seem to promise.

However, as Freda witnesses the courage of those involved in the sit-in protests and becomes more deeply moved by Darius’s leadership, she begins to reconsider what freedom truly means. Is it found in following the prescribed path of societal norms, or is it rooted in the willingness to challenge those very systems?

As Freda’s perspective shifts, the theme of societal expectations versus personal freedom becomes central to her journey, as she learns that true freedom may require breaking away from the constraints of tradition and embracing the risks that come with standing up for justice.

Love, Loyalty, and Personal Relationships

Throughout People of Means, Freda’s relationships—especially with Darius and Gerald—serve as a reflection of her evolving views on love, loyalty, and personal choices. Freda’s attraction to Darius, a passionate civil rights activist, and her ongoing relationship with Gerald, whom her parents deem a suitable match, reveal the complexities of love when set against the backdrop of societal pressures.

While Freda’s family hopes for a traditional, stable relationship with Gerald, Freda’s growing admiration for Darius challenges her to think beyond the confines of conventional romantic expectations. As the story progresses, Freda’s feelings for Darius deepen, leading her to question what loyalty means in the context of her relationships.

Gerald, despite his academic success and stability, becomes increasingly disconnected from Freda’s growing activism, which highlights the tension between her personal desires and her commitment to a larger cause. Similarly, Freda’s evolving relationship with her friends, Evaline and Cora, also highlights the complexity of loyalty and support.

The theme of love and loyalty explores the difficulties that arise when personal relationships are tested by differing values, desires, and commitments, especially when those values challenge the status quo.

Activism and Social Change

As Freda becomes more involved in the Civil Rights Movement, the theme of activism and social change becomes a driving force in her personal development. Initially, Freda is hesitant to engage with the protests, seeing them as a disruption to her academic focus and a risky distraction.

However, her experiences, including witnessing the protests at McLellan’s and the mistreatment of Black activists, compel her to reassess her stance. The movement becomes a way for Freda to not only challenge the systemic racism that has plagued her community but also to discover her own role in the struggle for equality.

Her increasing involvement in activism, from participating in protests to supporting the movement financially, reflects her growing commitment to social justice. The tensions between Freda’s academic ambitions and her desire to fight for racial equality highlight the internal conflict many activists face when trying to balance personal aspirations with larger societal goals.

Through Freda’s journey, the narrative illustrates how activism is not just a response to injustice but also a transformative process that shapes an individual’s identity and purpose.