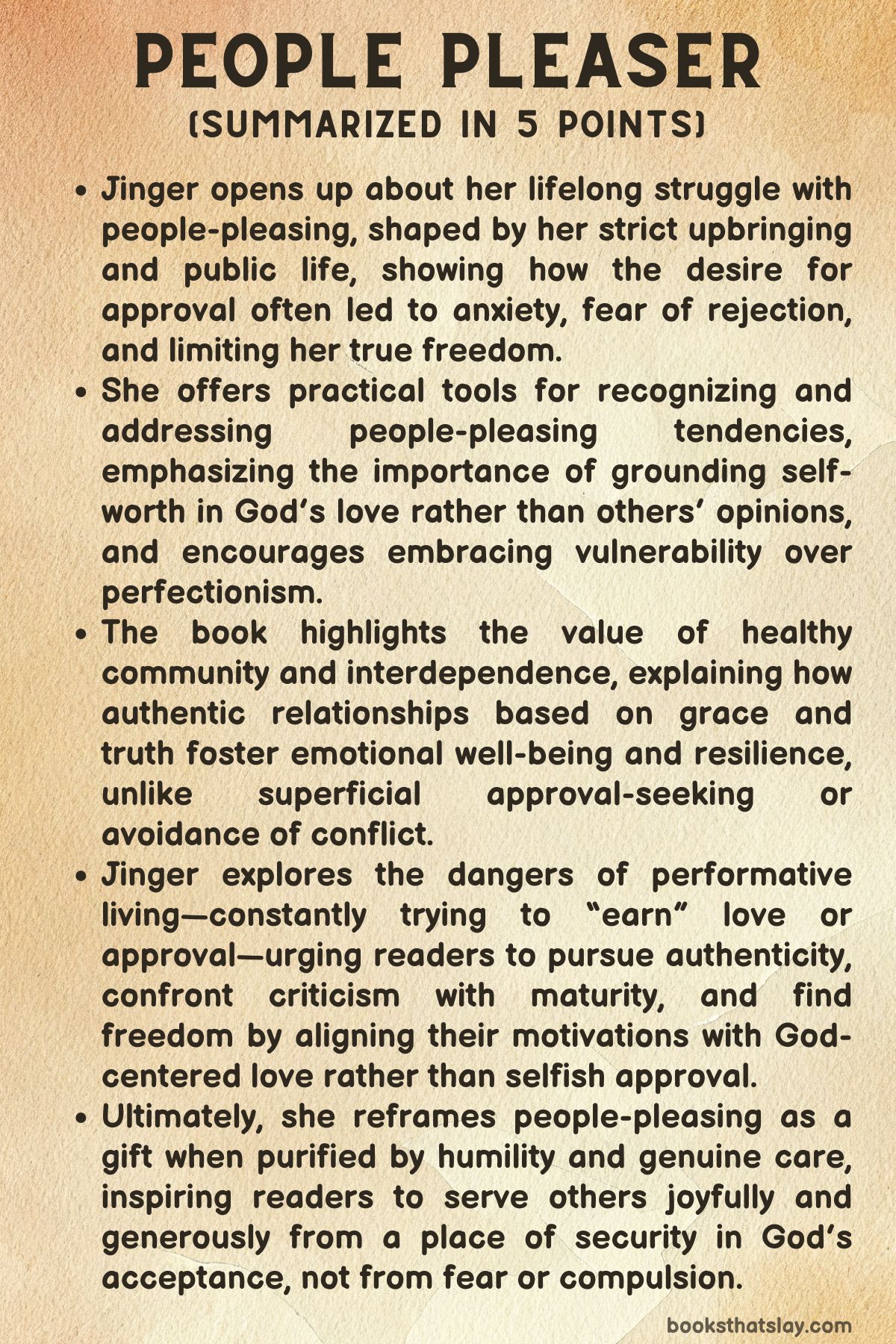

People Pleaser Summary, Analysis and Themes

People Pleaser by Jinger Duggar Vuolo is a candid and reflective memoir chronicling her journey from a life dominated by the need to appease others to one rooted in authentic faith and personal freedom. Raised in a highly controlled religious environment and growing up under public scrutiny, Jinger details how performance-based approval shaped her identity and strained her emotional well-being.

Through honest storytelling, scriptural insights, and personal transformation, she illustrates the emotional, spiritual, and relational costs of people pleasing—and how she learned to exchange that burden for peace, purpose, and connection rooted in God’s unconditional love.

Summary

People Pleaser opens with Jinger Duggar Vuolo recounting a period in her early marriage where anxiety overshadowed seemingly happy moments. While she and her husband, Jeremy, were establishing a home in Laredo, Texas, and hosting friends in their cozy apartment, she often felt dread and unease beneath her cheerful exterior.

That emotional dissonance led her to examine the deeper causes of her discomfort, which she eventually identified as the lifelong pattern of people pleasing—a habit she didn’t fully recognize until she began writing her earlier book, Becoming Free Indeed. This discovery marked the beginning of an introspective journey to understand how performance, approval-seeking, and fear governed her choices, behaviors, and self-worth.

As she reflected on her upbringing, Jinger traced the roots of her compulsion to please back to her childhood, where strict rules, religious legalism, and public visibility created an environment where perfection was expected and mistakes felt like moral failures. Her fear of disappointing others, especially those in spiritual authority or close family, led to suppressed desires and a constant effort to perform righteousness.

In social situations, she became anxious not because of the people themselves, but because she was consumed by thoughts of how she might be judged or misunderstood.

Relocating to Los Angeles offered Jinger a shift in perspective. While her fears didn’t vanish, the new environment gave her enough distance from familiar expectations to begin evaluating her behavior with fresh eyes.

With her husband’s support, she started unpacking her fears through open conversations, counseling, and spiritual reflection. She realized that her compulsion to people please had originally developed as a way to feel safe and loved, but over time it stifled her authenticity and joy.

Her healing process involved learning to ask better questions about her motivations, accepting her limitations, and allowing herself to be seen as imperfect.

In the next phase of the book, Jinger discusses the universal human longing for connection and how that longing can be twisted when people seek belonging through performance. Sharing personal memories from childhood—such as feeling awkward during fast-food outings or constrained by modesty rules during playful activities—she demonstrates how small acts of kindness made her feel truly seen and loved.

She explains that genuine connection, rather than image control, is God’s intention for humanity. Through biblical stories and scientific observations about aging and well-being, she underlines that deep relationships, not achievements, are what sustain people through life.

The book shifts focus to the theme of desperation, describing how people often engage in self-sacrificing or irrational behaviors just to be accepted. She uses an anecdote about her brother shocking himself on an electric fence to illustrate how the desire to fit in can override self-care.

Jinger connects these experiences to broader spiritual principles by analyzing the story of Martha and Mary. While Martha anxiously performed for Jesus, Mary sat with Him.

Jesus gently redirected Martha—not because service was wrong, but because striving for approval distracted her from true presence. The takeaway is that people pleasing often stems from misplaced priorities and must be replaced by hope and trust in authentic relationships.

Jinger then explores the consequences of “trading down”—sacrificing meaningful relationships or peace of mind for short-term comfort or approval. She likens this to Esau trading his birthright for a bowl of stew, noting how people pleasing causes individuals to trade vulnerability for image, and deep connection for superficial harmony.

Her personal reflections reveal moments where she chose to stay emotionally guarded, which ultimately led to isolation rather than protection. Through the story of Jonah, she encourages readers to stop running from discomfort or divine calling, reminding them that God offers second chances even when fear causes detours.

The following chapter addresses the inner critic—those internalized voices of judgment that are often more damaging than external criticism. Jinger recounts how online parenting critiques and past teachings fed her internal anxiety.

She contrasts this with Jesus’ interaction with the adulterous woman, showing that conviction leads to freedom while condemnation leads to shame. She encourages readers to let the “light of grace” into the dark corners of their minds rather than locking themselves in greenhouses of self-protection.

Healing begins by confronting fear with truth.

Chapter seven takes on the fear of failure and embarrassment. Jinger shares a humorous yet revealing story involving a grocery store incident that was captured by paparazzi.

While such moments once would have mortified her, she eventually laughed at herself, illustrating how her capacity for self-acceptance had grown. She opens up about how she used to hide her mistakes to protect her image—a coping mechanism shaped by being on reality television and living under rigid expectations.

In marriage, Jeremy’s unconditional support helped her feel safe enough to be imperfect. She draws a parallel to Adam and Eve hiding in the garden, explaining that shame often causes people to isolate when what they need is connection and grace.

Jinger discusses how vulnerability must be handled with wisdom. While it’s important not to hide behind perfection, she warns against oversharing without discernment.

Safe, mature relationships—those where honesty is met with compassion—are essential for healing. Scriptural commands to “bear one another’s burdens” and “confess sins” are seen not as religious obligations but as invitations to genuine community.

Her personal anecdotes highlight how shared laughter, awkwardness, and honesty can build stronger bonds.

As the book nears its close, Jinger encourages readers to examine their motivations behind service. People pleasing, she explains, is not always obvious.

Sometimes, it masquerades as kindness or humility. The key difference lies in motive—serving out of love versus performing for praise.

She illustrates this distinction through metaphors like snake venom (dangerous in one form, healing in another) and biblical references to sincere service. She presents a three-step model to shift from harmful people pleasing to healthy, Spirit-led service: recognize desperation-based motives, reject self-centered filtering, and embrace joyful, grace-fueled action.

Boundaries are redefined not as self-serving barriers but as tools for navigating unsafe situations wisely. The story of a woman anointing Jesus with perfume is offered as an example of intentional and meaningful service.

Prioritizing core relationships like family is encouraged while maintaining openness to those in need around us.

Jinger closes by reflecting on spiritual gifts and the unique roles individuals play in God’s plan. She emphasizes that the very areas where people feel most insecure or attacked are often where they’re meant to thrive.

Biblical stories such as the boy with loaves and fishes and the widow at Zarephath serve as reminders that God multiplies even the smallest offerings when they’re given in faith. Ultimately, she leaves readers with a message of freedom: that identity doesn’t rest on being perfect or liked but on being known, loved, and called by God.

By walking in truth and releasing the need for approval, people can live more joyfully, love more freely, and finally be at peace with themselves.

Key People

Jinger Duggar Vuolo

At the heart of People Pleaser is Jinger Duggar Vuolo herself, whose emotional, spiritual, and psychological evolution becomes the spine of the narrative. Jinger presents herself not just as an author recounting events, but as a soul unraveling decades of internalized fear, anxiety, and performance rooted in her upbringing and public life.

From her earliest memories of strict religious adherence to her roles within a high-profile reality television family, she internalized the message that love, worth, and safety came through rule-following and the avoidance of failure. Her anxiety in hosting social events, her dread of criticism, and her compulsion to perform in every area of life—from hospitality to faith—are manifestations of this learned behavior.

The emotional weight of constantly pleasing others, particularly the church community and public eye, slowly eroded her sense of self. Jinger’s transformation begins as she relocates to Los Angeles, where space—both literal and figurative—gives her the room to reflect, challenge old beliefs, and embrace vulnerability.

Her character arc is steeped in contradiction and grace. She does not merely abandon her past; she sifts through it with discernment, keeping the sacred while rejecting the toxic.

Her evolution is marked by moments of deep discomfort—exposing her thoughts publicly in Becoming Free Indeed, undergoing therapy, and embracing spiritual practices grounded in grace rather than legalism. Jinger’s embrace of metaphors—swimming in pants as a child versus learning to swim freely in Los Angeles—demonstrates how she translates spiritual insights into accessible, lived wisdom.

Her willingness to laugh at herself, even when the world is watching, shows a new resilience rooted not in flawless image maintenance but in humility and authenticity. Through confession, theological reflection, and relational transparency, Jinger emerges as a woman who is no longer defined by people’s approval but by her identity in Christ.

Her narrative invites others into this freedom, without pretending the journey is neat or fast.

Jeremy Vuolo

Jeremy Vuolo, Jinger’s husband, plays a transformative role in her healing journey. He is portrayed as patient, emotionally attuned, and steadfast—someone who doesn’t try to fix Jinger’s anxiety but instead gently encourages her to face it with honesty.

His reactions to her fears and insecurities stand in stark contrast to the judgment and pressure she internalized growing up. He is consistently shown offering a safe emotional space, asking questions rather than giving directives, and modeling a different kind of masculinity—one rooted in grace and curiosity rather than authority and rigidity.

His consistent presence becomes a mirror in which Jinger begins to see herself more clearly, not as someone failing to live up to impossible standards, but as someone worthy of love in her imperfection.

Jeremy also challenges Jinger, not with condemnation but with loving nudges toward growth. He invites her to take emotional risks, to let go of the need for control, and to embrace awkwardness and failure as essential parts of human connection.

His own willingness to be vulnerable—seen, for instance, in the humorous mishap of singing about low water pressure at a friend’s home—becomes a model for Jinger, reinforcing that embarrassment is survivable and even redemptive. His theological insights and emphasis on grace play a crucial role in helping Jinger reframe her understanding of God—not as a demanding taskmaster, but as a loving Father.

Jeremy is not just a supportive spouse in the narrative; he is a co-journeyer whose strength lies not in fixing but in walking alongside.

Jana Duggar

Jana Duggar, Jinger’s sister, makes a brief but symbolically rich appearance in the narrative. In the scene where the two work on a DIY closet renovation, Jana becomes a metaphorical guide—helping Jinger see that change is possible with the right tools, patience, and support.

This interaction highlights the contrast between Jinger’s past feelings of inadequacy and her emerging confidence to tackle challenges independently and imperfectly. Jana is not deeply explored as an individual character, but her role in that scene is pivotal in showing how relational support, especially from those who understand your background, can catalyze transformation.

Their sisterly bond, grounded in shared history, provides Jinger with a safe space to try, fail, and learn—a pattern that repeats throughout the book as Jinger experiments with new ways of living and believing.

The Inner Critic

Though not a person, the inner critic functions as a haunting character throughout People Pleaser, acting as an internalized voice of condemnation shaped by religious legalism, public scrutiny, and childhood conditioning. This voice doesn’t merely whisper doubts—it dominates Jinger’s decisions, relationships, and perceptions of self.

The inner critic tells her she must be perfect, that mistakes make her unlovable, and that vulnerability is weakness. Its presence is felt in her anxiety, her perfectionism, and her fear of criticism.

However, Jinger gradually learns to recognize this voice for what it is: a distortion. Through scripture, therapy, community, and reflection, she begins to counteract the inner critic with the truth of grace and love.

The eventual quieting of this voice signifies a major character shift—one where internal peace replaces internal tyranny.

God

God is perhaps the most central yet complex character in Jinger’s journey. He is not a static figure but one whose image evolves as Jinger disentangles legalism from faith.

Early in her life, God is perceived as a rule-keeper, a figure of fear whose approval must be earned through flawless living. This perception fuels Jinger’s people pleasing and anxiety, as she mistakenly conflates divine love with human approval.

Over time, however, she re-encounters God through scripture and experience as a being of grace, truth, and deep relational desire. This reorientation shifts everything: service becomes an act of joy rather than obligation, vulnerability becomes safe, and love becomes unconditional.

God is no longer the critical parent she must appease, but the loving Father who invites her into freedom. Her spiritual maturity unfolds as she embraces a theology of grace, slowly shedding the performative shell of her past.

Through God’s constancy, she finds the courage to be honest, to confess, to grow, and to lead others toward the same light.

Analysis of Themes

The Destructive Cycle of Performance-Based Approval

Performance-based approval is portrayed in People Pleaser as a subtle yet powerful form of bondage that shapes the author’s entire worldview from a young age. Jinger Duggar Vuolo’s upbringing, deeply entrenched in a public-facing religious subculture, demanded constant perfection and outward righteousness.

Mistakes weren’t just personal setbacks; they were interpreted as spiritual failures and potential public scandals. This environment taught her that her worth was tied directly to how well she could uphold rules, meet expectations, and perform morally in the eyes of others.

Over time, this cultivated a lifestyle in which authenticity was sacrificed for applause, vulnerability was mistaken for weakness, and love was seen as conditional. Even after marriage, this mindset persisted, coloring her relationships, faith, and sense of self.

Her anxiety in hosting guests and the dread of being judged—especially in how she might reflect on her husband—illustrate how deeply embedded this performance anxiety had become. The realization that this wasn’t a spiritual virtue but a psychological burden marks a pivotal moment in her healing.

Through counseling, candid conversations, and self-reflection, Jinger begins to see the cost of living for applause: isolation, exhaustion, and emotional dishonesty. The internal critic becomes a relentless judge, shaped by years of religious legalism and social expectation.

Healing, then, begins not with trying harder but with releasing the need to appear perfect and embracing grace. By learning that love and acceptance can’t be earned through performance, she gradually untangles her identity from the approval of others and reclaims it through faith and self-honesty.

The Fear of Vulnerability and the Instinct to Hide

The narrative repeatedly exposes the instinct to hide—whether it’s mistakes, insecurities, or flaws—as a central element of the people pleaser’s experience. Growing up under intense public scrutiny and religious rigidity, Jinger internalized the message that being truly seen—especially in weakness—was dangerous.

This fear manifests in mundane situations, such as fumbling with groceries, but also in deeper emotional patterns like avoiding difficult conversations or suppressing authentic reactions. The fear of being “found out” fuels what she calls the “Lonelies,” a state of soul-level isolation that begins when people believe they must earn their place in community by presenting a flawless version of themselves.

The biblical story of Adam and Eve hiding after their fall resonates throughout the text, not just as theology but as metaphor for the human condition. Hiding becomes a survival tactic, born from the lie that to be accepted, one must be unblemished.

This creates a paradox: in seeking to belong, people conceal the very parts of themselves that allow for true connection. Jinger explores how shame, pride, and fear feed this cycle, and how perfectionism is often a mask worn to avoid rejection.

Her transformation begins when she starts testing the safety of vulnerability—first in her marriage, where Jeremy’s unconditional love offers a model of grace, and later in friendships, where honesty fosters intimacy rather than shame.

Learning to confess, share burdens, and let herself be seen—especially in her faith journey—becomes not only a spiritual exercise but a therapeutic one. Vulnerability, rather than weakening her, strengthens her sense of self and reorients her understanding of God’s love as something unconditional.

The call to “olly olly oxen free” is not just about stepping into the light; it’s about believing that what is found there—grace, connection, and truth—is more healing than the safety of hiding.

The Desire for Control Masquerading as Selflessness

Control is shown to be a frequent companion to people pleasing, often dressed as sacrificial love but driven by fear and self-preservation. Jinger examines how behaviors that look like kindness or humility—always saying yes, avoiding conflict, going above and beyond—can actually be rooted in a need to manage others’ perceptions and ensure emotional safety.

These actions are not purely altruistic; they are transactions, hoping to buy approval or avoid judgment. She confesses how much of her service to others was filtered through the subconscious question, “Will this make them like me more?

” and how exhausting and hollow that pursuit becomes over time.

In religious terms, this kind of “service” is a distortion of Christlike love. The book emphasizes that true servanthood is led by the Spirit, not by fear or compulsive obligation.

The difference lies in motive: whether one serves out of freedom or compulsion, love or anxiety. When people pleasing is driven by desperation for control—of relationships, outcomes, or public opinion—it breeds resentment, burnout, and emotional detachment.

Jinger’s recognition of this pattern leads to a reframing of boundaries, not as selfish walls but as necessary protections for healthy giving. Boundaries allow for thoughtful, Spirit-led generosity instead of compulsive, fear-driven action.

The metaphor of antivenom is especially powerful here: the same drive that harms—pleasing for approval—can become healing when transformed. When control is released and love becomes the motive, acts of service gain authenticity.

By distinguishing between unhealthy compliance and joyful obedience, Jinger reclaims her agency and models how control can be surrendered without abandoning love or responsibility.

The Transformation from Desperation to Hope

Desperation is portrayed not simply as a feeling but as a driving force behind unhealthy choices and relationships. Jinger recounts stories—like her brother touching an electric fence to impress others—that highlight how the need to belong can override wisdom and self-protection.

This desperation is rooted in a fear of being unloved or excluded and often leads to compromise, anxiety, and spiritual disorientation. Rather than viewing this longing for connection as inherently flawed, she explains that the problem arises when it is misdirected—when hope is placed in human approval instead of divine truth.

What begins as a desire for relationship can devolve into a hunger for affirmation, leaving the soul empty and vulnerable to manipulation. The remedy, she suggests, is not to shut down desire but to redirect it.

Biblical stories like Martha’s anxious hospitality or Esau’s impulsive trade serve as moral mirrors, showing how desperation clouds discernment. Jinger contrasts these with stories of Jesus offering calm, clarity, and redirection—teaching that hope anchored in God allows people to be honest, steady, and at peace, even when others don’t approve.

This transformation is not abstract. It requires practical steps: learning to pause before saying yes, evaluating motives, and risking honesty in relationships.

Counseling, spiritual reflection, and community become tools for replacing desperation with discernment. Over time, Jinger learns to hope not in curated relationships but in a deeper assurance of worth and purpose.

This hope becomes a quiet strength, empowering her to serve, speak, and love without losing herself in the process.

Reclaiming Identity Through Grace and Spiritual Gifting

Throughout People Pleaser, the author’s journey is one of rediscovering her God-given identity apart from cultural, familial, or religious expectations. This reclamation begins with the dismantling of false identities shaped by performance, fear, and people pleasing.

But it does not end in deconstruction. Instead, Jinger rebuilds a sense of self rooted in grace, truth, and divine calling.

She explores how everyone has unique spiritual gifts meant for service and encouragement—not for comparison or competition. Her own experiences of feeling called to write, speak, and serve are reframed not as acts of ego or rebellion but as faithful responses to God’s leading.

This shift is reinforced through biblical metaphors: the widow who shares her last bit of oil, the child who offers five loaves and two fish. These stories serve as reminders that even small offerings can be multiplied when surrendered with faith.

Jinger challenges the belief that only grand, polished, or public acts matter. Instead, she affirms the power of simple, sincere obedience.

In doing so, she invites readers to examine their own talents and contributions, not through the lens of fear or inadequacy but through trust and gratitude.

Grace is presented as both a theological truth and a daily practice. It reshapes how one views failure, how one extends forgiveness, and how one chooses to engage with others.

By resting in grace, Jinger experiences new joy, deeper relationships, and a renewed passion for serving others—not as a people pleaser, but as someone free to give because she has already been given much. This sense of freedom and purpose is the ultimate fruit of her journey, and the gift she hopes to extend to others through her story.