Pickleballers by Ilana Long Summary, Characters and Themes

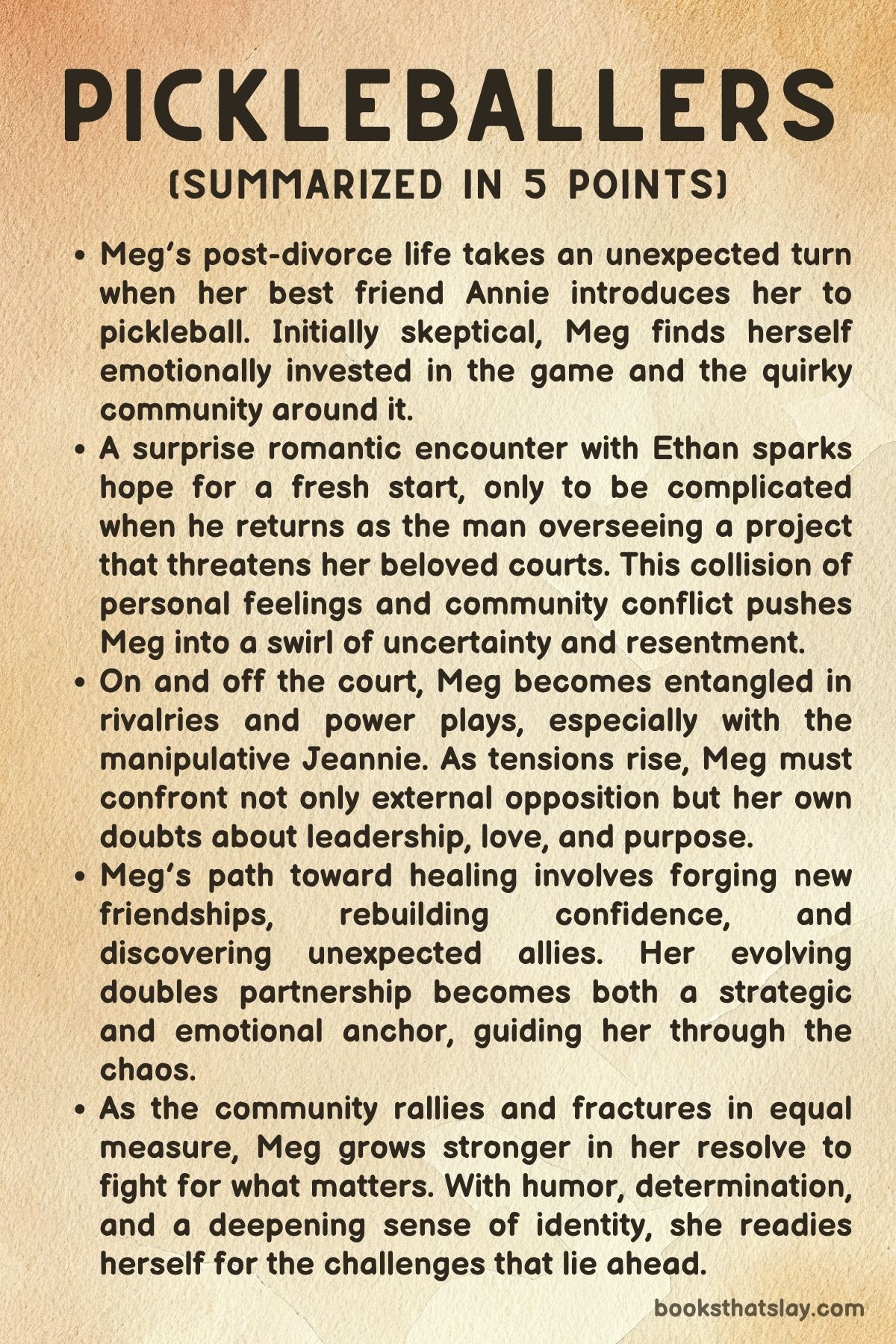

Pickleballers by Ilana Long is a heartfelt and humorous contemporary novel centered on the emotional rehabilitation of Meg Bloomberg, a recently divorced artist who reluctantly joins a local pickleball league. What starts as a reluctant hobby quickly becomes a lifeline as she struggles with heartbreak, redefines her identity, and finds solace in an unexpected community.

Set in the Pacific Northwest, the story blends emotional depth with laugh-out-loud moments, offering a resonant portrayal of middle-aged reinvention. With a dynamic cast of quirky players and complicated relationships, the novel uses pickleball not just as a game, but as a metaphor for resilience, self-discovery, and love.

Summary

Meg Bloomberg’s life hits rock bottom when her husband, Vance, leaves her with no explanation, just a scribbled note on the back of a receipt. In the throes of heartbreak, Meg’s best friend Annie encourages her to join a local pickleball game as a way to lift her spirits.

At first, Meg finds the game baffling and frustrating, but the physicality and simplicity of hitting a ball with a paddle offer her a strange sort of catharsis. While she initially resists Annie’s optimism, Meg starts to use the sport as an outlet for her grief, discovering a hint of satisfaction in her erratic swings and missed shots.

On Bainbridge Island, Meg delivers her last order for her embarrassing Crafty Cat Collars business, finally freeing herself from a phase she has outgrown. She feels a flicker of her old artistic inspiration during her ferry ride home, where she encounters a striking painting and an even more striking stranger named Ethan Fine.

A flirtation sparks over clam chowder and chemistry blooms, though the moment feels fleeting and disconnected from her real life.

Later, Meg and Ethan unexpectedly cross paths again in Seattle, leading to an impulsive and awkwardly hilarious almost-hookup in her car. They don’t exchange information, leaving Meg to assume it was a one-time adventure.

Despite this, she feels empowered by her own spontaneity. When she returns to the pickleball courts, Meg finds comfort in the community there, even as tensions rise with aggressive players like Jeannie.

She’s asked to represent the group at a school board meeting, only to be blindsided when she learns that the project lead threatening to remove the courts is none other than Ethan. Overwhelmed and betrayed, she leaves the meeting speechless.

The emotional turbulence continues as Meg’s divorce is finalized on the summer solstice, symbolizing both an end and the potential for new beginnings. Rooster, one of her older pickleball companions, offers encouragement, emphasizing that hardship is temporary.

This insight helps Meg start to rebuild emotionally, appreciating the power of resilience in small, consistent efforts—both on and off the court.

Meg’s involvement in the pickleball league deepens just as the community faces a threat: the local courts are at risk due to a proposed wetland restoration project, ironically spearheaded by Ethan. She tries to avoid the situation, even hiding in a portable toilet during a meeting, but her growing connection to the community compels her to take a stand.

The upcoming Picklesmash Tournament becomes a focal point of hope, with a $10,000 prize on the line and a requirement that each team include beginner players. Meg and Rooster are natural picks for this spot, but complications arise when Vance and his suspiciously proficient new girlfriend, Édith, return to town.

As the tournament nears, team dynamics grow strained. Jeannie, driven and hostile, threatens team unity.

Meanwhile, Meg wrestles with her lingering feelings for Ethan and her sense of inadequacy. During a rainy afternoon, she impulsively challenges Jeannie to a match to secure her spot as a beginner player, only to learn that Rooster will soon be leaving for Bainbridge.

Rather than give up, Meg decides to join him, seeking both a chance to train and an opportunity to reset emotionally.

On Bainbridge, Meg finds unexpected healing. A woman named Mayumi offers her room and board in exchange for painting the fence at her inn.

As Meg throws herself into the project, she begins reconnecting with her identity as an artist. The fence becomes a symbol of both division and connection, and painting it helps her process her emotional growth.

Ethan appears again, and together they paint and share stories, opening up in a way they hadn’t before. Ethan’s role as an environmental consultant, once viewed with suspicion, is now understood in a new light: he’s genuinely trying to balance preservation with community needs.

Their connection deepens with newfound honesty. They confess their past wounds and vulnerabilities—Ethan’s abandonment by his father, Meg’s fears stemming from her divorce—and tentatively rekindle their relationship.

This emotional rawness sets the stage for renewed trust and affection. A comical yet grounding interruption by Ethan’s eccentric mother Babs adds levity to their intense reconnection.

The story’s climax unfolds during the Picklesmash Tournament. Meg, Ethan, Annie, and Rooster arrive at Everest Park ready to represent their community.

Meg is anxious but supported by those who have become her tribe. The presence of Vance and Édith adds pressure, but Meg remains focused.

As she and Ethan begin competing, their coordination and understanding improve with each match. Their progress mirrors their relationship—tentative at first, but increasingly confident and unified.

Despite the temptation to disqualify Vance and Édith for ineligibility, Meg decides to win fairly. After a rocky start in the final match, she finds her rhythm and executes a miraculous shot that secures a dramatic victory.

Though Lakeview wins the tournament by a narrow margin, a surprise donation ensures that youth sports on Bainbridge also benefit. Meg’s perseverance pays off in ways both tangible and symbolic.

The epilogue jumps forward a year, showing Meg thriving. She and Ethan are a couple in love and artistic collaboration, working on eco-friendly mural projects together.

Annie and Michael, her friend’s new partner, are also thriving, using their wealth for philanthropic causes. In a romantic gesture, Ethan proposes to Meg using a custom pickleball delivered by their dog, Relish.

The novel concludes with the four friends enjoying a friendly pickleball match under the lights. It’s a moment that captures the essence of Meg’s journey: joy, resilience, community, and love.

What began as a reluctant hobby became the catalyst for transformation. In reclaiming her identity, Meg finds not only her place in the world but also the strength to shape her future, one rally at a time.

Characters

Meg Bloomberg

Meg Bloomberg stands at the emotional and narrative core of Pickleballers, her transformation anchoring the story’s themes of renewal, identity, and vulnerability. When readers first meet her, Meg is a woman devastated by her husband’s abrupt departure, left with nothing but a mocking note on a hardware store receipt.

This emotional trauma lingers at the forefront of her mind, coloring her early attempts to engage with the world again. Her journey is not marked by instant revelation or easy victories, but by halting steps forward, false starts, and moments of humbling awkwardness.

From crafting cat collars to reluctantly swinging a pickleball paddle, Meg initially presents as someone afraid to confront her true self and potential. Yet, it is precisely through the absurdity and challenges of pickleball that she begins to rediscover her voice and agency.

As the narrative unfolds, Meg’s character reveals rich emotional layers—she is not just a wronged ex-wife, but a deeply feeling artist who has allowed the loss of love to suppress her creative voice. Her impulsive flirtation with Ethan, her spontaneous hike into the mountains, and even her decision to challenge Jeannie for a spot in the tournament all reflect a growing hunger to reclaim control over her narrative.

Meg becomes a character who learns to embrace discomfort as a necessary prelude to change. Her progression from passive sufferer to active agent is reflected not only in her paddle swings but in her willingness to lead, to fight for her community, and to risk falling in love again.

By the end, she is not merely a woman healed by sport or romance, but one who has come home to herself, integrating pain, play, love, and purpose.

Ethan Fine

Ethan Fine enters the narrative with an air of charming spontaneity—a ferry café flirtation that soon turns into a catalytic presence in Meg’s life. He is at first a mystery, his role and motivations unclear, particularly when he reappears as the project manager overseeing the potential demolition of the beloved pickleball courts.

Yet, rather than casting him as a romantic antagonist, the novel peels back Ethan’s emotional armor in a way that complements Meg’s own journey. As an environmental consultant, he embodies a kind of principled professionalism that complicates the morality of the court conflict, but his personal history, especially his trauma over paternal abandonment, renders him emotionally textured and vulnerable.

What makes Ethan compelling is his dual nature: he is both a source of disruption and a figure of stability. His chemistry with Meg is immediate, but their relationship is repeatedly challenged by miscommunication, past wounds, and external obstacles.

His confrontation with Meg about her tan line reveals his longing for emotional honesty and security—a trait that deepens the reader’s empathy. The turning point in his character comes during the mountaintop cabin conversation, where he fully exposes his insecurities.

It is in this moment that Ethan shifts from being a romantic possibility to a deeply relatable partner, one willing to do the emotional labor required for intimacy. By the conclusion of Pickleballers, Ethan stands not only as Meg’s partner but as someone whose own evolution—from guarded consultant to supportive teammate and loving fiancé—mirrors the book’s larger message of growth through vulnerability.

Annie

Annie, Meg’s best friend, is a figure of warmth, optimism, and relentless support. A pediatric doctor, Annie embodies both practicality and emotional intelligence, acting as Meg’s emotional anchor throughout the novel.

From introducing Meg to pickleball to encouraging her during romantic and artistic crises, Annie functions as both confidante and comedic relief. Her own subplot—falling for Michael Edmonds only to discover his engagement—adds emotional dimension to her character, proving that her sunny demeanor doesn’t exempt her from heartbreak.

Despite her personal pain, Annie never recedes into bitterness. Her decision to accompany Meg on a treacherous mountain hike in search of solace and clarity highlights her loyalty and emotional courage.

Annie is not merely a sidekick; she is a character grappling with her own search for love and self-worth. Her eventual pairing with Michael and their shared philanthropic work adds a fulfilling arc to her storyline, one that reflects the larger themes of healing, renewal, and community.

Annie’s unwavering support is instrumental in Meg’s growth, but her own evolution—from love-struck vulnerability to empowered action—cements her as a fully realized character whose presence enriches every page she occupies.

Rooster

Rooster is one of the story’s most endearing and grounded characters—a quirky older man whose combination of court savvy and philosophical insight provides balance and levity. Rooster becomes a gentle mentor to Meg, helping her navigate both the literal pickleball court and the metaphorical game of life.

His role is not flashy, but it is indispensable; he sees Meg not as a broken woman, but as someone in need of reflection and redirection. His most poignant contribution comes in the form of emotional guidance: his reminder to Meg that her pain is temporary and her capacity for growth immense is one of the story’s most touching moments.

Rooster’s unexpected hand injury is more than a plot twist—it becomes a catalyst for Meg’s independence. It symbolically shifts the responsibility of action from mentor to mentee, forcing Meg to rise to the occasion.

Rooster’s move to Bainbridge Island and his quiet presence at pivotal moments reinforce the novel’s motif of transition. His character serves as a bridge between generations, between past and future, and between despair and resilience.

Though never at the center of the romantic or dramatic conflicts, Rooster is the heartbeat of the community, his eccentric wisdom leaving a lasting impact on Meg and readers alike.

Vance and Édith

Vance, Meg’s ex-husband, is less a fully developed character and more a lingering wound personified. His abrupt departure—without explanation, without confrontation—establishes the emotional chasm from which Meg must emerge.

His reappearance alongside Édith, his stylish and suspiciously athletic new partner, feels like a cosmic slap in the face, one that reopens old insecurities for Meg. Yet Vance’s smugness and lack of emotional accountability only serve to highlight Meg’s growth.

He is a foil rather than a true rival, a reminder of who Meg used to be and who she refuses to become again.

Édith, while given minimal backstory, functions as a subtle antagonist. Her elegance and polished demeanor serve as an emotional contrast to Meg’s messier, more earnest path.

Together, Vance and Édith represent the performative success Meg once chased and now rejects. Their defeat on the court is symbolic—Meg triumphs not through vengeance, but through authenticity and teamwork.

In the end, they are important not for who they are, but for what they provoke in Meg: a final, liberating confrontation with the past.

Jeannie

Jeannie is one of the most complex secondary characters in Pickleballers, beginning as an abrasive, hyper-competitive figure whose confrontational nature destabilizes the pickleball community. She antagonizes Meg in the early chapters, often serving as an obstacle to camaraderie and cohesion.

Yet, Jeannie is never portrayed as a flat villain. Her intensity and ambition mask deeper fears about aging, relevance, and self-worth—concerns that mirror Meg’s in unexpected ways.

The turning point for Jeannie comes not through conflict, but through unexpected resolution. Her eventual reconciliation with Meg reveals a more vulnerable side, suggesting that her hostility was a projection of internal turmoil rather than true malice.

Her acknowledgment of Meg and Ethan’s contributions to the Lakeview victory shows grace and self-awareness, allowing her to evolve beyond the stereotype of the “mean girl” competitor. Jeannie’s arc, like many in the novel, is about learning to let go—of ego, of bitterness, and of the need to win at all costs.

Her character adds texture to the story’s message that even the fiercest battles can lead to unexpected understanding.

Mayumi

Mayumi, the soft-spoken hotel owner on Bainbridge Island, provides a sanctuary both literal and metaphorical for Meg. She is the keeper of a space where healing becomes possible—not through advice or interference, but through quiet observation and gentle presence.

Her offer to let Meg paint the fence in exchange for room and board is a subtle but powerful act of trust, giving Meg the chance to rebuild her identity as an artist and as a woman with something to offer.

Mayumi’s history with Bainbridge Island and her nuanced understanding of people imbue her character with a sense of timeless wisdom. She becomes a mirror for Meg’s evolution, offering a space for contemplation rather than intervention.

In a story brimming with high energy and interpersonal drama, Mayumi’s quietude is grounding. Her presence underscores the importance of safe spaces and stillness in the midst of emotional storms.

Through her, Pickleballers pays tribute to the unsung heroes of transformation—the ones who make healing possible simply by holding space.

Themes

Healing Through Community and Shared Purpose

Meg Bloomberg’s transformation throughout Pickleballers is deeply tied to her gradual immersion in a supportive, sometimes chaotic, but ultimately restorative community. Initially isolated and emotionally wrecked by her husband’s abandonment, Meg enters the world of pickleball almost accidentally.

What begins as a half-hearted attempt to get out of the house quickly becomes the foundation for rebuilding her sense of identity. The pickleball courts aren’t just recreational spaces—they serve as a public arena for connection, conflict resolution, and belonging.

Through interactions with Annie, Rooster, and even her adversaries like Jeannie, Meg discovers that healing isn’t a solitary journey. It is in the communal rituals of play, encouragement, and shared setbacks that she finds resilience.

Whether it’s defending the court from demolition, training for a tournament, or learning to negotiate tense group dynamics, Meg finds that being part of something larger than herself invites her back into life. The community gives her a sense of stakes and responsibility, forcing her to advocate not only for a physical space but also for the people who have come to matter to her.

Even conflict becomes an opportunity for growth, as it pushes her to make decisions she would have once avoided. The narrative positions healing not as a quiet, internal retreat but as an active, outward-facing process catalyzed by shared experiences and collaborative efforts.

Reclaiming Identity and Creative Agency

Meg’s journey is also a quest to reclaim her sense of self as both an artist and a woman with agency. The divorce shatters her sense of worth, leaving her adrift in roles that feel performative and disingenuous—like her job crafting cat collars.

The absurdity of dressing piglets becomes a metaphor for the superficiality she’s been trapped in, highlighting how far she’s veered from her passions. The chance to paint the inn’s fence on Bainbridge Island becomes a turning point.

The fence, an ordinary structure, transforms into a canvas of self-expression and possibility. As Meg literally paints her way back into purpose, she also begins to rewrite her internal narrative—from someone who has been abandoned and silenced to someone who creates, defines, and chooses.

Her flirtation and eventual relationship with Ethan serve not as the end goal but as a mirror for her evolution. When she finally accepts her desire to paint again—not for survival but for meaning—it signifies her return to authorship of her own life.

She stops reacting and begins to act, guided not by fear or heartbreak but by instinct and desire. The creative process itself becomes restorative, offering not only beauty and release but also clarity about what matters.

Through art, Meg reconstructs both her emotional stability and her sense of agency.

Emotional Risk and the Necessity of Vulnerability

Throughout Pickleballers, characters are repeatedly pushed into situations where emotional vulnerability becomes unavoidable. Meg, in particular, resists this at every turn.

Her initial coping mechanism is withdrawal, evident in her avoidance of confrontation and her tendency to deflect with sarcasm or physical escape—hiding in porta-potties, storming off courts, or choosing a treacherous mountain path rather than deal with emotional tension. However, these avoidance strategies only lead her deeper into moments of reckoning.

It is on that precarious hike, facing danger and failure, that she begins to understand the value of exposing her inner fears. The late-night conversation with Ethan in the mountaintop cabin—where both of them share traumas they’ve long kept hidden—underscores the importance of transparency.

Ethan’s childhood abandonment and Meg’s shame over her failed marriage are not romantic confessions but genuine emotional disclosures. These moments don’t resolve their issues but instead build a foundation for trust.

Vulnerability in this story is framed not as weakness but as the condition for meaningful intimacy, friendship, and even play. Meg’s final willingness to risk public failure during the Picklesmash Tournament, and her refusal to win through technical disqualification, is a further extension of this emotional courage.

She chooses the riskier, more exposed route, and in doing so, achieves personal and communal victories. Vulnerability is no longer a threat but a pathway.

Transformation Through Play and Embodied Experience

The sport of pickleball functions as more than a plot device—it becomes the medium through which Meg’s transformation is physically enacted. Her initial wild swings, performed in a state of grief, begin as catharsis.

Yet over time, her movement becomes more intentional, her play more strategic. The sport offers a rare combination of spontaneity and structure, providing both the space for expression and the demand for discipline.

In this way, pickleball mirrors Meg’s inner journey. The tournament format—with its rules, brackets, and pressures—requires her to confront failure publicly, recalibrate under stress, and trust others in ways she has long avoided.

At the same time, the physicality of the sport forces her into her body. After a period of emotional dissociation, where she has numbed herself against feeling, the quick reflexes and sweat of the court bring her back into the present.

Physical play becomes its own form of language, a way for Meg to test boundaries, connect, and eventually thrive. Even her final victory, the whimsical yet miraculous Golden Pickledrop, symbolizes this confluence of effort, luck, and embodiment.

Play is not treated as childish or escapist, but as a serious venue for emotional engagement, risk-taking, and transformation.

Forgiveness, Acceptance, and Moving On

Meg’s arc cannot be fully understood without recognizing how forgiveness and acceptance operate in the background of every major decision. She is surrounded by characters who challenge her ability to let go of grudges and disappointments—her ex-husband Vance, his smug partner Édith, the competitive Jeannie, and even Ethan in his colder moments.

Each of these figures forces her to decide what kind of narrative she wants to live in: one shaped by resentment and reactivity, or one guided by grace and perspective. Her choice to forgo disqualifying Vance and Édith in the tournament reflects not just fairness but an emerging sense of integrity.

She no longer needs revenge to assert her worth. Her reconciliation with Jeannie, too, shows a capacity to revise opinions and allow space for others to grow.

Importantly, forgiveness in Pickleballers isn’t about denying harm or pain; it’s about releasing oneself from their long-term grip. Acceptance becomes a means of regaining power—not by erasing the past but by refusing to let it define the future.

The final scenes, with their communal laughter and spontaneous play, show characters who have made peace with imperfections, both in themselves and each other. The story argues that real closure comes not from perfect resolutions but from the choice to keep playing, keep connecting, and keep showing up.