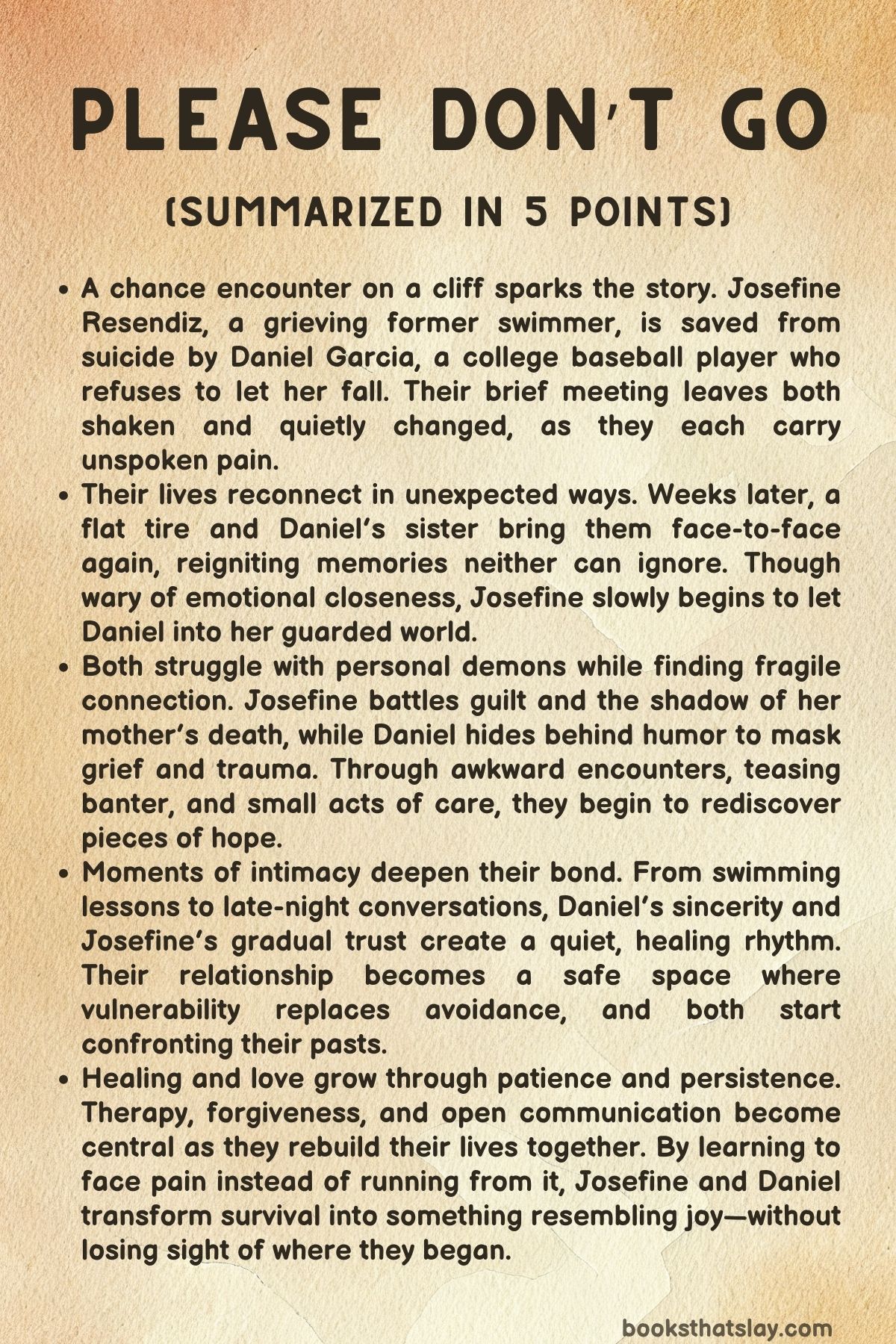

Please Don’t Go Summary, Characters and Themes

Please Don’t Go by E. Salvador is a contemporary new adult romance exploring love, healing, and the lingering shadows of loss.

It follows Josefine Resendiz, a former collegiate swimmer burdened by trauma and grief, and Daniel Garcia, a baseball player hiding behind a cheerful façade while fighting his own pain. Their story begins at a cliff on Christmas Eve, where Daniel stops Josefine from ending her life with three simple words: “Please don’t go.” What follows is a tender, emotionally charged journey of two broken people learning to trust, to feel, and to choose life again—together—amid the quiet echoes of their shared darkness.

Summary

Josefine Resendiz, a former swimmer at Monterey Coastal University, stands at the edge of a cliff on Christmas Eve, ready to end her life. She feels detached from everything, her existence consumed by numbness and despair.

Just as she’s about to jump, Daniel Garcia, the university baseball shortstop, intervenes. He doesn’t try to reason with her at first; he simply stays, talks, and reaches out until she finally breaks down and lets him hold her.

His repeated plea—“Please don’t go”—becomes a turning point. When dawn comes, Josefine leaves a note saying she didn’t jump.

Daniel, haunted and uncertain of her fate, can’t stop thinking about her.

Days later, he and his friend Angel revisit the cliff on New Year’s Eve, hoping to see her again. She doesn’t appear, but Daniel finds a strange comfort in knowing he tried to save her.

Meanwhile, Josefine survives but lives like a ghost. She teaches children to swim, going through the motions without joy.

One night, when her tire blows out, a kind girl named Penelope stops to help her—Penelope, it turns out, is Daniel’s sister. Daniel soon arrives, and the two are stunned to see each other again.

They awkwardly reconnect as he helps her with the tire and insists on ensuring she gets home safely. Inside her home, he admits he needed to see if she was real—alive.

Their brief, vulnerable exchange rekindles something quiet between them. The next morning, Daniel leaves a note on her door, offering his number and writing, “I’m so happy you’re here.

Josefine later refuses a coaching job offered by Monica Jameson, her late mother’s rival, unwilling to face swimming’s reminders of loss. She maintains her fragile routine until she joins a hiking and photography class, where she unexpectedly runs into Daniel again.

His warmth and persistence chip at her defenses, and though she resists, he brings small moments of life into her numb existence. Slowly, their paths begin to merge once more.

Daniel, who narrates part of the story, hides his grief beneath humor. During their hiking class, he and Josefine are paired as partners, forcing them to interact.

Their playful conversation hints at a budding connection—she chooses invisibility as a superpower, symbolizing her desire to vanish, while he picks elemental control. When she finally smiles, he feels a spark of hope.

Later, Daniel’s teammates reveal that Josefine once dated Bryson, the same teammate who betrayed Daniel by sleeping with his ex. The revelation complicates Daniel’s emotions but also deepens his empathy for her.

Josefine’s perspective reveals her cautious friendship with Penelope and Vienna, two women who slowly pull her into their social circle. Daniel’s persistence continues: he emails her asking for swimming lessons, claiming he doesn’t know how to swim.

She suspects a joke but later realizes he’s sincere. When they meet for lessons, tension simmers between them—he’s afraid of water, and she’s afraid of feeling again.

Gradually, trust forms. At a party, when her drunk ex Bryson harasses her, Daniel intervenes quietly, shielding her without overstepping.

Their shared pain begins to align into mutual understanding. Daniel promises her one semester to make her feel again.

She warns him not to try—but deep down, she hopes he will.

Their connection deepens through shared vulnerability. Josefine, once repelled by baseball, finds herself watching Daniel play.

His confidence on the field mesmerizes her, though jealousy surfaces when she hears others gossip about him. That night, she returns home to find her house filled with yellow flowers—his gift.

When she finds him crying outside, their confrontation softens into intimacy. They play a revealing game where each secret requires removing an item of clothing, trading stories of loss: his late brother Adrian, her demanding mother, their shared grief.

Their emotional honesty transforms into passion, culminating in a tender, physical union that marks the beginning of something deeper than either expected.

As weeks pass, they continue to orbit each other—Daniel cooking for her, sharing music, and taking swimming lessons to conquer his fears. She gradually opens up, laughing more, finding lightness in his presence.

Still, both struggle with guilt: Daniel for using her as a lifeline for his unresolved trauma, and Josefine for feeling happiness she thinks she doesn’t deserve. Their relationship is fragile yet real, built on compassion and quiet care.

When Daniel gifts her a CD titled “Danny’s Holy Grail of Happiness,” they bond over music, memories, and shared pain. She eventually helps him face his fear of water; during a swim lesson, their trust culminates in a passionate embrace, symbolic of healing through closeness.

Yet, their journey isn’t without collapse. Both begin therapy separately after a painful fallout.

Josefine starts confronting her anxiety and grief over her mother’s death, while Daniel begins sessions with therapist Jarvis to address trauma from witnessing his brother’s drowning. In time, therapy helps them both reclaim agency over their lives.

When Daniel returns after a month away, he finds Josefine at an aquarium and confesses he’s getting help, taking medication, and trying to heal. They reconcile, exchanging “I love you” for the first time and promising not to hide anymore.

Together, they unpack their shared trauma—the cliff incident, his guilt, her despair—and vow to walk through the darkness side by side.

Their friends rally around them, helping Daniel move in with Josefine. Domestic scenes—cleaning, cooking, quiet laughter—replace the chaos that once ruled their lives.

Daniel returns to baseball; Bryson apologizes for past cruelty, and Daniel forgives him for the sake of closure. During a game, he writes “I’m very taken” on a baseball tossed to a fan, publicly acknowledging his love for Josefine.

She, meanwhile, accepts a student assistant position under Monica, finding strength in returning to the sport that once broke her.

By summer, Daniel can finally swim unaided, symbolizing his emotional freedom. Josefine cheers for him as he conquers the deep end, the same place that once terrified him.

Their growth is mirrored—he’s learned to stay afloat, and she’s learned to live again. Seven years later, they live together in Seattle, Daniel now a professional baseball player and Josefine a swim coach at Seattle State University.

On Christmas Eve, they revisit the cliff—the place where their story began. This time, she carries a gift: a positive pregnancy test.

Overwhelmed, Daniel promises unwavering support. Standing together where death once tempted her, they embrace life and the family they’re about to begin.

Their story, once marked by pain and survival, closes in quiet triumph. They didn’t just save each other that night—they chose to keep saving one another, every day after.

Please Don’t Go becomes not a plea of desperation, but an affirmation of love, growth, and staying.

Characters

Josefine “Josie” Resendiz

Josefine is the emotional heart of Please Don’t Go, a young woman trapped between grief, guilt, and the slow rediscovery of life. Once a promising swimmer, her mother’s death and the pressure of living in her shadow lead her into an emotional collapse.

Her first appearance—standing on the cliff’s edge, ready to die—captures her utter detachment from the world. Her numbness isn’t born from weakness but from years of loneliness and loss that hollowed her spirit.

The encounter with Daniel becomes the first fracture in her despair; his desperate “please don’t go” reawakens something fragile within her—a sense that she still matters.

Throughout the story, Josefine’s journey is one of reluctant healing. She resists attachments, fearing they’ll lead to more pain, yet life continually pushes her toward connection.

Her work as a swim instructor is both a coping mechanism and a punishment—an echo of the sport she associates with her late mother. As she reconnects with Daniel, and later with friends like Penelope and Vienna, we see the slow thawing of her isolation.

Josefine’s relationship with Daniel is not an easy romance but a mirror of her emotional recovery: hesitant, tender, and sometimes self-destructive. By the novel’s end, she chooses to live—not because life is suddenly beautiful, but because she has learned that love and pain coexist.

Her evolution from despair to quiet resilience embodies the book’s central message of survival through connection.

Daniel “Danny” Garcia

Daniel serves as the story’s emotional counterpart to Josefine—his charm and humor conceal deep-seated guilt and grief. Outwardly a confident athlete and beloved teammate, Daniel carries the trauma of his brother Adrian’s death and the crushing weight of pretending to be okay.

His attempt to save Josefine at the cliff isn’t only an act of compassion but a subconscious effort to save himself. From that moment, she becomes a symbol of redemption, a person whose survival gives meaning to his own pain.

As the narrative unfolds, Daniel’s complexities emerge. His inner turmoil contrasts his cheerful façade; his love for baseball, his family, and even his banter with friends are coping mechanisms against emptiness.

His growing bond with Josefine allows him to express genuine emotion without fear of judgment. Their intimacy—both physical and emotional—reveals Daniel’s capacity for empathy and patience, qualities that make his healing believable.

His therapy later in the novel is pivotal, marking his acceptance that love alone cannot fix trauma. By the end, Daniel stands as a man who has reclaimed both purpose and peace, not by burying his pain but by acknowledging it.

His final moments with Josefine at the cliff symbolize closure—revisiting a place of death and turning it into a beginning.

Penelope Garcia

Penelope, Daniel’s sister, is the novel’s emotional grounding force. She represents the kind of steady, unconditional love that both Daniel and Josefine lack in their fragmented lives.

Initially cheerful and somewhat naive, Penelope’s warmth and optimism contrast the darkness surrounding the main characters. Her decision to befriend Josefine without judgment shows her instinctive compassion.

As the story progresses, she becomes a bridge—reconnecting Josefine and Daniel, but also helping Josefine rebuild trust in friendship.

Penelope’s apology to Josefine later in the story is one of the book’s quiet yet powerful moments. It reflects the maturity to admit when love—familial or otherwise—has been imperfectly expressed.

Her presence during the final chapters, alongside Vienna, reinforces the idea that healing is communal. Penelope embodies stability, love, and hope—the familial warmth both main characters need to rebuild themselves.

Vienna “Vi”

Vienna provides levity and groundedness in a story heavy with emotional weight. As a performer and friend, she embraces joy in a way that contrasts sharply with Josefine’s initial emptiness.

Her friendship is not intrusive but patient, gradually coaxing Josefine out of isolation. Vienna’s confidence, humor, and lack of pretense make her a mirror of what Josefine could become—a woman comfortable in her own skin.

Vienna’s teasing about Daniel and her refusal to let Josefine retreat into cynicism introduce moments of genuine warmth. Through her, the novel explores the role of friendship as a form of emotional rehabilitation.

She doesn’t push Josefine toward romance or redemption but toward living honestly. By the end, her continued presence in Josefine’s life symbolizes the sustainability of healing beyond romantic love.

Monica Jameson

Monica functions as both a mentor figure and a symbolic link to Josefine’s past. As a former rival of Josefine’s mother, she represents the legacy Josefine struggles to accept.

Her offer of the assistant coaching position is more than a professional opportunity—it’s a test of whether Josefine can confront the ghosts tied to swimming and her mother’s memory. Monica’s compassion and understanding show her awareness that healing cannot be forced.

Monica’s role in arranging therapy for Josefine underscores her subtle wisdom. She recognizes that support means guidance, not pressure.

By encouraging rather than coercing Josefine, Monica becomes a quiet catalyst for her transformation. She represents the world’s gentler, patient side—the kind that waits for broken people to find their own way back.

Bryson

Bryson is the shadow figure of the story—the embodiment of toxic masculinity, insensitivity, and unresolved guilt. As both Daniel’s teammate and Josefine’s ex, he personifies the pain both characters carry from their past relationships.

His cruelty, especially during the party scene, underscores how trauma can be perpetuated through indifference and mockery. Yet his later apology to Daniel, though brief, marks an important thematic shift in the narrative.

Bryson’s presence is a reminder that closure doesn’t always come through revenge or punishment. Sometimes, acknowledgment—however imperfect—is enough to signal change.

His character arc, though small, illustrates the possibility of personal accountability and growth, even among those who once contributed to others’ suffering.

Claudia Resendiz

Claudia, Josefine’s late mother, hovers over the novel like an unspoken ghost. Though she never appears directly, her influence shapes nearly every choice Josefine makes.

A celebrated swimmer, Claudia’s perfectionism and emotional distance left Josefine yearning for approval she could never earn. Her death cements the cycle of guilt and inadequacy that drives Josefine toward the cliff.

Through memories and conversations, Claudia becomes a symbol of legacy and expectation—what it means to live in the shadow of someone else’s success. Yet by the story’s conclusion, Josefine’s acceptance of the coaching job signifies her reconciliation with that legacy.

She learns to separate her mother’s love from her mother’s flaws and to reclaim swimming as her own. Claudia’s unseen presence, therefore, becomes the haunting melody of the novel—a reminder that love, even imperfect, leaves a lasting imprint.

Themes

Healing and Emotional Resurrection

Josefine’s journey in Please don’t go begins at the brink of death, suspended between the desire to disappear and the faint, unacknowledged pull of life. Her encounter with Daniel becomes the first moment she is forced to confront the fact that she is still capable of being seen, touched, and saved.

The act of being physically pulled back from the cliff becomes a metaphor for the slow emotional resurrection that defines the novel. Healing in this story is not swift or miraculous; it is fractured, marked by hesitation, relapse, and quiet progress.

Josefine learns to exist again through small acts — teaching children to swim, sharing meals, joining a photography class, and allowing people to occupy the empty spaces in her life. Daniel’s presence does not cure her despair but gives her a reason to engage with her pain.

The novel frames healing as a partnership of vulnerability — one person’s courage to reach out meets another’s willingness to be held. Both Daniel and Josefine find that recovery demands confronting trauma rather than evading it.

Their love is not built on saving each other but on creating room for the other’s brokenness. By the end, healing is portrayed as an accumulation of moments — a conversation, a shared laugh, a step forward — where living becomes a choice reaffirmed each day.

The Burden of Grief and Memory

Grief in Please don’t go operates as an ever-present shadow, shaping identity, behavior, and relationships. Josefine’s mourning for her mother is not simply loss but an inheritance of pressure, guilt, and silence.

Her mother’s legacy as a celebrated swimmer turns water — once a space of comfort — into a mirror reflecting her inadequacy. Daniel’s grief, too, is heavy, defined by the drowning of his brother Adrian, a trauma that manifests as insomnia, avoidance, and guilt disguised beneath cheerfulness.

Both characters carry the weight of what they could not prevent — a death they were too late to stop, a person they could not save. Memory becomes both torment and tether; they cling to reminders of the past while longing to escape them.

Through therapy, conversation, and shared pain, the narrative suggests that grief does not vanish but transforms. By speaking their losses aloud, Josefine and Daniel reclaim control over memories that once controlled them.

The novel captures grief as cyclical — it resurfaces unexpectedly but softens with understanding and acceptance. Their eventual decision to revisit the cliff symbolizes the reclaiming of a memory once dominated by despair, converting it into a symbol of continuity, love, and life renewed.

Love as Redemption and Responsibility

The relationship between Josefine and Daniel unfolds not as a typical romance but as an emotional reckoning between two people trying to survive themselves. Love here is an act of responsibility — a conscious choice to stay, to listen, to hold space for pain that might never fully disappear.

Daniel’s insistence on caring for Josefine, even after her attempts to push him away, challenges the notion that love must always be easy or mutual at first. His affection is patient but not idealized; he struggles with guilt, jealousy, and fear of inadequacy, yet continues to show up.

Josefine, on the other hand, fears dependence and vulnerability, equating love with loss. Their intimacy is built through communication, touch, and small gestures — notes, lessons, and moments of honesty that signal the rebuilding of trust.

Love becomes a mirror reflecting their own self-worth: to accept love, each must learn to believe they are deserving of it. By the end, when both admit “I love you,” it is not a declaration of escape but of endurance.

Their love does not erase their pain; it simply redefines it, turning it into a shared burden they are willing to carry together.

Identity, Legacy, and Self-Worth

Josefine’s struggle to separate her identity from her mother’s shadow forms a central emotional thread. Her refusal to accept the assistant coaching job at first reflects a deep internal conflict — the fear that she will forever be a reflection of Claudia Resendiz rather than her own person.

The pool, once her place of triumph, becomes a graveyard of expectations. The novel portrays the suffocating nature of legacy: how familial success can feel like a debt rather than an inheritance.

Through her interactions with Monica and Daniel, Josefine begins to rediscover swimming not as a reminder of failure but as a connection to both her mother’s memory and her own autonomy. The journey toward self-worth is marked by incremental acceptance — that she can honor her mother without being consumed by her image.

Her decision to eventually return to coaching symbolizes reclamation, transforming what once symbolized pressure into purpose. This theme extends to Daniel as well, who learns that he does not need to replicate his late brother’s dream to honor his memory.

Both characters find identity not in comparison or achievement but in authenticity — in the quiet courage to exist for themselves, not through others’ expectations.

The Continuum of Mental Health and Recovery

Please don’t go treats mental health not as a condition to be conquered but as a lifelong process requiring patience, honesty, and support. Both protagonists confront depression and trauma in different forms — Josefine’s numb detachment and suicidal ideation, Daniel’s anxiety and guilt-induced restlessness.

The inclusion of therapy later in the narrative grounds their recovery in realism. Healing is not romanticized; therapy sessions are described as exhausting, progress as uneven, and relapse as part of the journey.

The story dismantles the myth of instant recovery, showing that love alone cannot replace professional help. Yet, it also celebrates the importance of human connection as a complement to treatment.

Daniel’s necklace with the safety pin becomes a tangible reminder of his commitment to stay alive, symbolizing the merging of love, therapy, and self-discipline in sustaining recovery. The narrative’s final chapters — showing both protagonists maintaining therapy, stable careers, and a growing family — reflect the continuity of mental health rather than its conclusion.

Recovery here is an act of persistence, of learning to live beside pain rather than in its shadow, and of replacing hopelessness with the steady rhythm of daily resilience.