Pomona Afton Can So Solve a Murder Summary, Characters and Themes

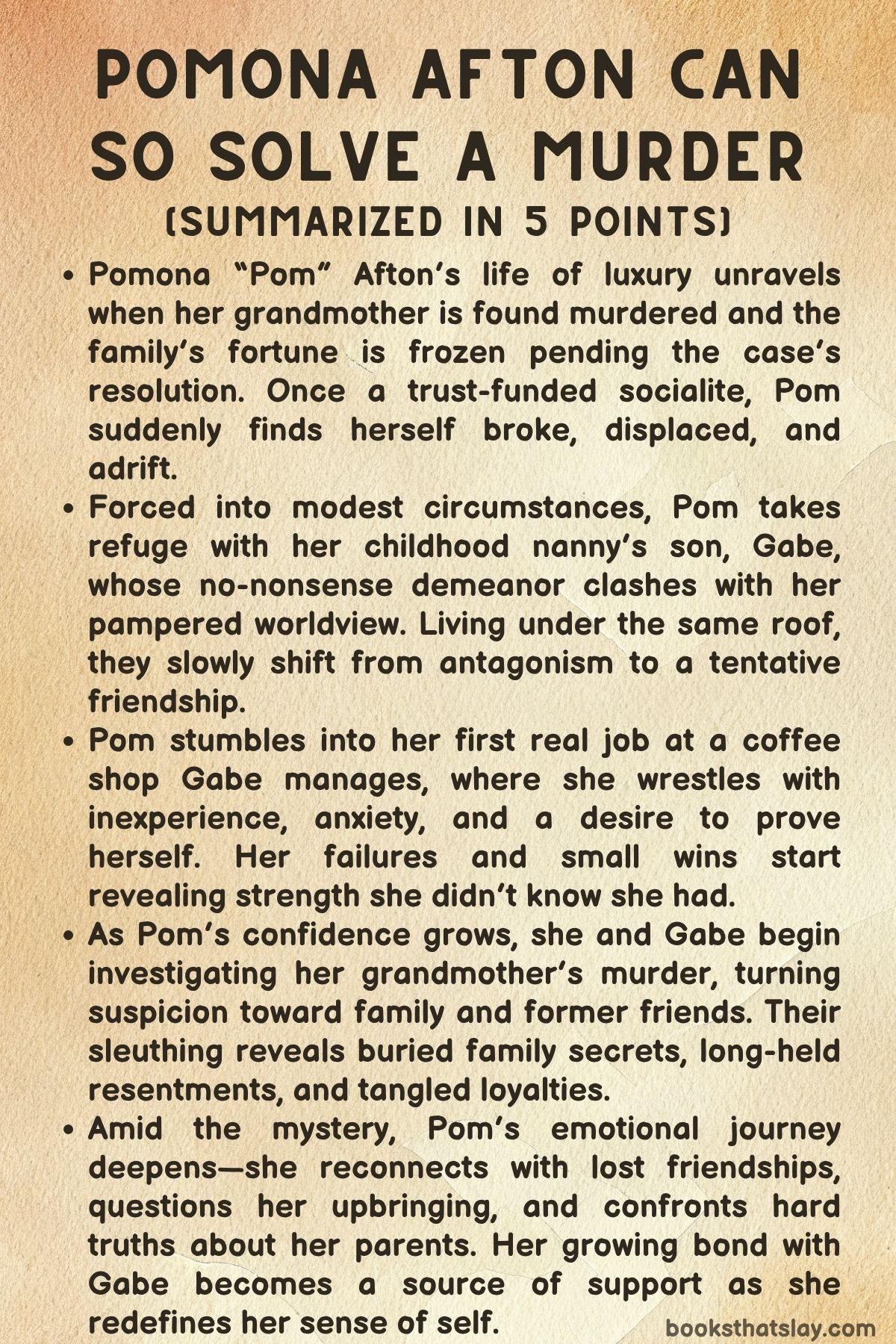

Pomona Afton Can So Solve a Murder by Bellamy Rose is a sharp, witty, and emotionally layered contemporary mystery that follows the fall and rise of Pomona “Pom” Afton, a spoiled heiress forced to rebuild her life after the sudden, brutal murder of her powerful grandmother. Once cocooned in designer clothes, socialite parties, and a plush trust fund, Pom finds herself cut off from her wealth and suspected of being connected to the crime.

Faced with an unrecognizable life of couch-surfing, minimum-wage jobs, and family secrets, she reluctantly begins her own investigation. What starts as a desperate attempt to regain her privilege becomes a transformative journey of identity, purpose, and justice.

Summary

Pomona Abigail Afton—known as Pom—is introduced as a privileged young woman from a wealthy hotel dynasty. Her life is defined by excess and detachment.

She’s spent her twenties drifting from failed ventures to extravagant galas, earning the reputation of the family disappointment. Her brother, Nicholas, is the golden child and business heir, while Pom remains adrift, leaning heavily on her trust fund and social status.

On the day her life changes, Pom wakes up hungover and ignores repeated calls from her formidable grandmother Marion Afton, only to later discover Marion stabbed to death in her penthouse suite. The tragedy is shocking, but the aftermath is what truly upends Pom’s life.

Marion’s will includes a clause freezing all family assets if she dies under suspicious circumstances. With no money or housing, Pom is evicted and quickly finds herself without any support.

Her brother’s hospitality is awkward and short-lived, and her attempts to rebrand herself as a lifestyle influencer fail when the public sees her behavior as tone-deaf. Estranged from most of her friends, Pom reaches out to Andrea, her old nanny, and moves in with Andrea’s son Gabe.

Their relationship begins with friction, worsened by class differences and old wounds, but softens slightly when Pom discovers her childhood cat—now renamed Meatball—is living with Gabe. The cat becomes an odd bridge between them.

Pom is woefully unprepared for life outside of luxury. She can’t cook, clean, or navigate public transportation.

Gabe offers her a job at his café, which she accepts only because she’s broke. Her first attempt is a disaster, ending in a panic attack, but she gets a second chance under an alias.

Pom slowly starts to adapt to her new world, her arrogance giving way to resilience. The death of Andrea, Gabe’s mother and her former nanny, becomes a shared point of grief that further connects them.

Eventually, Pom and Gabe agree to investigate Marion’s murder. They form a suspect list that includes family members and close associates.

Their efforts yield small breakthroughs but also cause tension, especially after an early meeting with the company’s CFO ends in an argument. Pom begins to discover she’s far more capable than she’s ever been allowed to believe.

She uses her social skills and intuition to gather information, piecing together motives and timelines. Their suspect pool includes Pom’s cousins Farrah and Jordan, Nicholas and his girlfriend Jessica, and Opal—one of Pom’s former best friends.

The mystery deepens when Pom overhears a suspicious phone conversation between her parents, revealing that her mother might be involved in Marion’s murder. Though Gabe wants to go to the police, Pom insists on gathering more evidence first.

She starts making small strides toward independence—applying for jobs, selling brownies at Gabe’s café, and beginning to enjoy the feeling of productivity. Her growing confidence is tested when her socialite identity is exposed, leading to public humiliation and a painful run-in with Vienna, her once-best friend.

Gabe comforts her during this low point, and their friendship begins to evolve into something deeper.

Further suspicion falls on Nicholas after Pom visits him and finds him evasive. A trip to her parents’ house uncovers more inconsistencies: her mother admits to an argument with Marion involving a thrown stiletto heel, but denies committing the murder.

She also confirms that Nicholas and Jessica visited Marion after she left, casting suspicion in their direction. Determined to find proof, Pom enlists Gabe and Opal to help her sneak into the hotel and retrieve security footage from the night of the murder.

Just as they’re close to succeeding, they’re caught by security. Gabe kisses Pom to distract the guard, revealing both romantic tension and increasing stakes.

Pom and Gabe reconcile after the botched footage heist, solidifying their personal and investigative partnership. They share their first real romantic moment, rooted in mutual respect and growing affection.

Gabe reaffirms that his interest in solving the case is no longer about money but about supporting Pom. Their next big breakthrough happens after Pom reconnects with Vienna and makes peace with their falling out, realizing how much she’s changed from the selfish socialite she once was.

Their reconciliation symbolizes Pom’s transformation and acknowledgment of her past failures.

The final clue comes when Pom and Gabe confront Opal at her Queens apartment. Pom records the encounter secretly, and when Opal discovers this, a physical altercation ensues.

In the chaos, Opal confesses: she is Pom’s secret aunt, born from an affair between Pom’s grandfather and her mother. After discovering the truth through a DNA test, Opal approached Marion for recognition and support but was rejected cruelly.

Enraged, she murdered Marion with the stiletto heel. Gabe arrives with the police just in time, and the confession is secured on tape.

The story then skips ahead a year. Pom has rebuilt her life on her own terms.

She opens a successful bakery called Pomona’s Treats, maintains a steady and loving relationship with Gabe, and starts a foundation that supports food and education initiatives. Her relationships with people like Vienna, her cousins, and even her emotionally distant parents have stabilized, if not entirely healed.

At the bakery’s opening, surrounded by those who stayed and those who returned, Pom reflects on how far she’s come. She no longer defines herself by her wealth or her family’s name but by her choices, her relationships, and her work.

The novel closes on a humorous note, with Gabe teasing her about solving another murder. Pom, now grounded and sure of herself, insists that one solved mystery is enough.

Her journey from a performative, entitled party girl to a self-possessed woman capable of love, purpose, and independence forms the emotional core of Pomona Afton Can So Solve a Murder, blending coming-of-age insight with the intrigue of a murder mystery.

Characters

Pomona Abigail Afton (Pom)

Pomona, the protagonist of Pomona Afton Can So Solve a Murder, begins as a caricature of wealth and frivolity, a Manhattan socialite with more sarcasm than direction. She is introduced as a woman who’s cushioned by generational affluence, dismissive of responsibility, and addicted to the performance of luxury.

Her identity revolves around parties, curated appearances, and the cynical expectation that she will always fall short of her family’s expectations. However, the sudden death of her grandmother and the freezing of the family’s assets catapult her into a life of struggle, forcing a painful reckoning.

As Pom is stripped of her status and forced to navigate real-world challenges—poverty, labor, public scrutiny—she begins to shed her defensive armor. Her vulnerability gradually transforms into grit.

The murder investigation becomes both a literal and symbolic path to self-discovery, wherein Pom evolves from a passive figure into someone assertive, curious, and morally accountable. By the novel’s end, she isn’t just solving a crime—she’s reclaiming her agency, redefining her worth, and building a life that is no longer dictated by legacy but by earned purpose.

Gabe

Gabe is the reluctant roommate, coffee shop manager, and eventual love interest who acts as Pom’s tether to reality. Initially gruff, unimpressed by Pom’s former social standing, and emotionally distant, Gabe represents the stability and moral clarity Pom lacks.

His life, though modest, is rooted in care—he’s the son of Andrea, Pom’s old nanny, and his grounded worldview often clashes with Pom’s extravagant background. Yet beneath his blunt exterior is an empathetic heart.

He offers Pom her first job, supports her entrepreneurial efforts, and respects her need for growth. As their relationship deepens, Gabe becomes Pom’s emotional confidant, encouraging her to see herself beyond the lens of her family’s judgment.

His belief in justice—not just legal, but emotional—is unwavering, even when it risks their bond. The tenderness he shows during Pom’s lowest moments, paired with his fierce protection of those he loves, makes him a crucial catalyst in Pom’s transformation.

Their romantic evolution, while subtle, is steeped in emotional intimacy and mutual respect, and Gabe ultimately becomes not a savior, but a steady partner in Pom’s reclamation of her life.

Marion Elizabeth Hunter Afton

Marion, Pom’s powerful and imperious grandmother, is a force even in death. As the matriarch of the Afton dynasty, she looms over the narrative like a ghostly standard of control, wealth, and conditional affection.

Her expectations for Pom were sharp-edged, and her death leaves behind more than a vacuum of power—it unearths decades of manipulation, silence, and emotional neglect. While she is never present in the narrative’s “now,” her influence drives the plot: the murder investigation, the inheritance drama, and the psychological unraveling of the family.

Marion’s cruelty becomes especially haunting when the details of her interactions with Opal are revealed. Her refusal to acknowledge a secret daughter and her unapologetic elitism speak to a legacy of coldness and transactional love.

Yet her death inadvertently opens the door for Pom’s liberation and growth, making Marion both the instigator of the story’s crisis and the symbolic embodiment of a toxic legacy Pom must learn to escape.

Andrea

Andrea is the quiet, stabilizing figure whose presence is felt through both memory and maternal warmth. As Pom’s childhood nanny and Gabe’s mother, she bridges the divide between the elite and working-class worlds.

While not central to the murder plot, Andrea’s legacy lives on through her influence on both Pom and Gabe. She represents the only form of unconditional love Pom likely received in childhood.

Her apartment—modest but warm—is a sanctuary where Pom is allowed to unravel, be comforted, and, most importantly, rebuild. Andrea’s off-stage death before the novel begins becomes another layer of grief that both Pom and Gabe process together, further strengthening their bond.

Her spirit hovers around the novel’s emotional core, reminding the characters of what real care looks like in contrast to the transactional relationships within Pom’s family.

Nicholas Afton

Nicholas, Pom’s older brother, is the golden child of the Afton family—competent, favored, and entrenched in the family business. On the surface, he plays the role of the dutiful son and heir, but as the investigation unfolds, layers of deception and guarded behavior reveal a man driven more by self-preservation than morality.

His defensiveness, secretive meetings, and vague alibis cast suspicion on him, and his loyalty to the family legacy appears more important than justice or emotional truth. Nicholas’s relationship with Pom is complicated.

He vacillates between condescension and protectiveness, often treating her as incapable or childish, while also harboring guilt and fear about their family’s dysfunction. Ultimately, he symbolizes the pull of legacy and tradition, the idea of upholding appearances at all costs, and he serves as a stark contrast to Pom’s eventual rejection of that same path.

Jessica

Jessica is Nicholas’s girlfriend, a well-meaning outsider trying to assimilate into the ruthless Afton world. She is kind and polite, but ill-equipped to navigate the high-society dynamics and power plays that define Pom’s family.

While initially depicted as awkward and forgettable, Jessica becomes more intriguing as she is implicated in the mystery. Her role evolves from passive bystander to potential accomplice, complicating her image and adding moral ambiguity to her character.

Through Jessica, the novel explores the fragility of belonging and the pressures of assimilation. She is often caught between loyalty to Nicholas and discomfort with the Afton ethos, and this tension makes her presence more complex than it first appears.

Opal

Opal undergoes one of the most dramatic reveals in the novel. Introduced as one of Pom’s old socialite friends, she is initially portrayed as quirky, supportive, and eccentric—an echo of the carefree party lifestyle Pom used to embody.

But the story slowly peels back her layers to reveal a woman fueled by grief, rejection, and buried identity. Opal is, in fact, Pom’s aunt—born from a secret affair and denied recognition by the Afton family.

Her murder of Marion, committed in a moment of rage and desperation, is rooted in the emotional violence of being erased and denied justice. While her act is undeniably horrific, the novel presents her with pathos, forcing readers to grapple with the human cost of generational cruelty and exclusion.

Opal’s descent into violence is not just the climax of the murder plot, but the emotional crescendo of the novel’s themes around truth, legacy, and identity.

Vienna

Vienna, once Pom’s best friend and now a bitter ex-ally, represents the ideological rift that separates performative socialites from those seeking genuine impact. Her “cancelation” early in the story is the result of moral convictions that clashed with Pom’s complacency, particularly around issues of class and responsibility.

Vienna’s reappearance later in the novel is charged with emotional weight, as it forces both women to confront the pain of their broken bond. Their reconciliation is one of the novel’s most poignant moments, highlighting the potential for healing and shared purpose.

Through Vienna, Pom learns the value of using privilege for good, and their reunion signals the beginning of a more purpose-driven chapter in Pom’s life.

Farrah and Jordan

Farrah and Jordan, Pom’s cousins, are portrayed with a mix of affection and ambiguity. Their initial portrayal is light, social, and somewhat superficial—representatives of the Afton bubble.

However, as suspects in the murder, they become more enigmatic. Their involvement in Pom’s emotional healing, particularly through the art gallery visit, suggests a shared desire to escape the suffocating expectations of their lineage.

Though not central to the murder plot, their presence helps illustrate the broader psychological toll of growing up in a world defined by money, silence, and image maintenance. They serve as both mirrors and foils for Pom, showing alternate paths through the same terrain of privilege.

Pom’s Mother

Pom’s mother is one of the most toxic forces in the novel. Dismissive, emotionally abusive, and self-absorbed, she sees Pom not as a daughter but as a failure to be mocked.

Her caustic phone calls, flippant bets about Pom’s survival, and disturbing implication in the murder build a character defined by denial and cruelty. Yet even she is granted a sliver of nuance—her outbursts stem from years of repression and bitterness, and her final confessions reveal a woman caught in the same web of Afton dysfunction as everyone else.

Still, her refusal to support or truly love Pom marks her as one of the greatest antagonists in Pom’s emotional journey.

Pom’s Father

Pom’s father is more shadow than presence, complicit in his wife’s schemes and disappointments, and emotionally absent in his daughter’s life. His role in covering up the potential murder implicates him not just legally but morally, cementing his loyalty to his wife over truth or justice.

He exemplifies the passive corruption of the Afton patriarchs—men who protect the family name even at the cost of ethics and love. His silence and avoidance contribute significantly to Pom’s feelings of abandonment and betrayal.

Squeaky / Meatball

Squeaky, later renamed Meatball by Gabe, is Pom’s childhood cat and an unexpected symbol of continuity and emotional healing. His reappearance in Gabe’s apartment triggers memories of simpler, more innocent times.

The cat becomes a shared point of connection between Pom and Gabe and a small, grounding comfort amid chaos. Squeaky’s quiet, nonverbal presence contrasts with the dramatic upheavals of the plot, offering subtle emotional resonance and a touch of tenderness.

Together, these characters weave a tapestry of privilege, pain, discovery, and transformation, animating the heart of Pomona Afton Can So Solve a Murder and ensuring that its murder mystery is as much about inner reckoning as it is about external justice.

Themes

Class and Privilege

The tension between class structures and personal identity forms a central thread throughout Pomona Afton Can So Solve a Murder. Pom’s early life is entrenched in a Manhattan elite defined by excess, reputation, and generational wealth.

Her social existence is dictated not by who she is, but by what her last name affords her. When the death of her grandmother freezes the family’s assets, the loss of her financial cushion forces Pom into a reality she’s never experienced—one where her surname offers no safety net.

Her confusion over public transportation, her disastrous first day at a coffee shop, and her inability to cook dinner without burning it aren’t played for laughs as much as they are windows into how profoundly ill-equipped she has been made by a life of abundance. What she undergoes is not a typical “riches to rags” trope, but a confrontation with the consequences of having been shielded from labor, accountability, and basic self-sufficiency.

Her interactions with Gabe and other working-class characters complicate her understanding of what defines competence, strength, and purpose. By the end, Pom’s earned success with her bakery is not just a return to status—it’s a redefinition of worth, where value arises from effort and community rather than inheritance.

The novel ultimately critiques how insulated wealth can become corrosive, leaving even the privileged emotionally bankrupt and morally stagnant.

Family Dysfunction and Emotional Abuse

The Afton family operates with the appearance of legacy and prestige but is internally decaying under the weight of manipulation, favoritism, and unresolved resentment. Pom’s position as the perceived “failure” of the family is less the result of actual incompetence and more a product of emotional neglect and impossible standards.

Her grandmother’s coldness, her parents’ cruelty—evidenced by their casual bets on her failure—and her brother’s condescension all reinforce an environment where love is conditional and power is prioritized over connection. These dynamics have stunted Pom’s emotional development, leaving her with few tools to form trust-based relationships or believe in her own abilities.

Her discomfort around genuine affection, particularly with Gabe, reflects her upbringing in a household where vulnerability was punished or mocked. The novel doesn’t resolve these familial relationships with full catharsis, and that’s intentional.

Her parents remain emotionally distant, and her reconciliation with her brother is cautious rather than complete. However, by creating her own chosen family—through Gabe, Opal (before the betrayal), and later Vienna—Pom starts to unlearn the emotional scaffolding built by her family.

The story illustrates how dysfunction isn’t always explosive; sometimes, it’s insidious, manifesting as silence, disapproval, and transactional affection.

Identity and Self-Worth

Pom’s journey from an ornamental socialite to a self-motivated entrepreneur represents the heart of the novel’s exploration of identity. At the outset, she measures her value through public perception, curated Instagram posts, and the approval of a high-society circle that quickly abandons her when her wealth disappears.

Her performative lifestyle masks a deep insecurity shaped by a lifetime of being told she doesn’t measure up. Working under the alias “Rachel” at the café becomes symbolic—it allows her to experiment with being someone untethered from legacy or reputation.

Ironically, it’s when she’s pretending to be someone else that she begins to discover who she actually is. Her transition is not sudden but built through small, cumulative moments: selling brownies that become popular, being complimented for her instincts, managing a confrontation with a suspect, and later resolving interpersonal tensions with friends like Vienna.

By the novel’s end, Pom’s identity is no longer dependent on inherited prestige but on earned integrity. She isn’t perfect—still learning, still a bit sharp-tongued—but she is no longer pretending, which makes her self-worth more grounded and authentic than ever before.

Female Anger and Suppressed History

Throughout the novel, women are shown not just as victims or objects of patriarchal systems but as complex agents with buried rage and unrealized histories. Marion Afton, though domineering, is revealed to have withheld painful family secrets, including the existence of Opal, her husband’s illegitimate daughter.

Opal’s murder of Marion is not born purely out of greed, but from the anguish of being denied acknowledgment and respect—a lifetime of rejection culminating in one violent, irreversible act. Even Pom’s mother, who confesses to throwing a stiletto at Marion, is driven by years of accumulated bitterness and rivalry.

These layers of suppressed emotion complicate the portrayal of women in the narrative. They are not caricatures of ambition or trauma, but products of generational silence, each responding in flawed but deeply human ways.

Pom, in contrast, begins to break this pattern. Instead of allowing her pain to calcify into hatred or violence, she channels it into purpose.

By the end, the novel reframes female anger not as something shameful or destabilizing, but as a valid response to centuries of erasure, worthy of being heard, understood, and transformed.

Justice and Moral Complexity

Solving the murder is not just a narrative hook but a metaphor for restoring balance in a world riddled with moral ambiguity. Every character becomes a potential suspect, and with that comes the unsettling realization that no one is entirely innocent.

Pom’s investigation isn’t driven by pure idealism—initially, it’s motivated by the desire to get her trust fund back and regain stability. But as the investigation deepens, she begins to see the toll of silence and complicity.

She’s confronted with the horrifying possibility that her own mother might be involved and later, the devastation of realizing her closest friend is the murderer. There’s no simple justice here.

Opal’s confession is both damning and pitiable. Pom chooses not revenge, but truth.

She records Opal not to entrap her maliciously, but to protect herself and ensure accountability. Gabe’s presence underscores this moral thread—he grounds Pom in the belief that justice should not only serve the living but also honor the dead.

The resolution doesn’t bring total healing, but it reestablishes Pom’s belief that justice can be an act of care rather than punishment, a step toward rebuilding rather than just tearing down.

Redemption and Second Chances

Pom’s fall from grace is the catalyst for a narrative fundamentally concerned with second chances—not just for her, but for nearly every major character. Gabe, too, is rebuilding his life after personal loss.

Vienna’s reentry into Pom’s life offers the chance to repair a fractured friendship born from ideological and emotional misunderstandings. Even Pom’s decision to give her family one more chance to show up for her bakery opening is an act of cautious optimism.

What distinguishes these redemptions is their earned nature. Pom doesn’t magically become competent or selfless overnight.

Her growth is steeped in effort, in learning from missteps, in asking for forgiveness and offering it. The novel insists that redemption is not about being perfect—it’s about trying again with intention.

When she decides to stay with Gabe, open her café, and reinvest her time in meaningful causes, she isn’t trying to “undo” the past but to build forward. Her journey reflects the uncomfortable but empowering truth that second chances are rarely given—they are made, forged through discomfort, humility, and hope.