Private Rites by Julia Armfield Summary, Characters and Themes

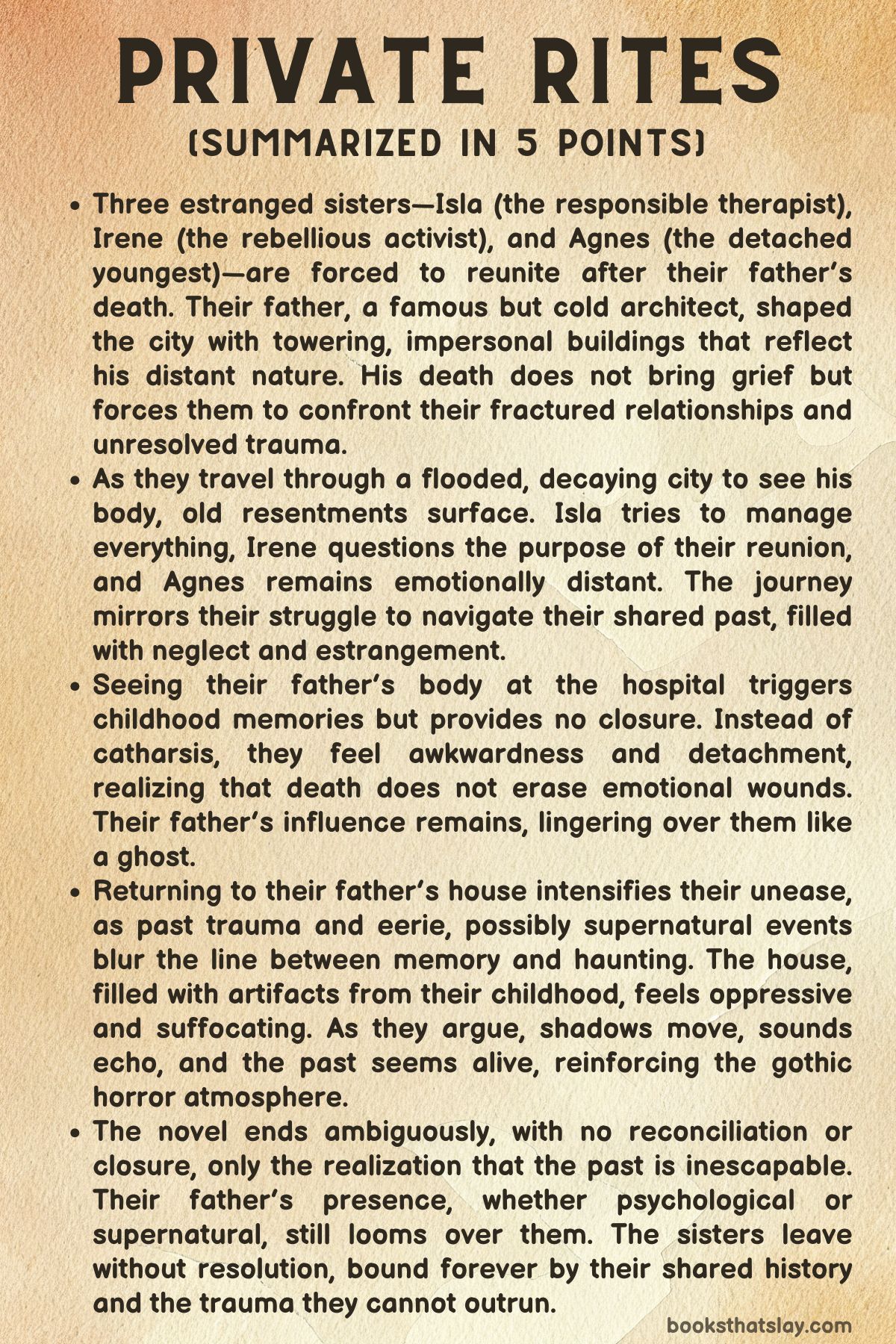

Private Rites by Julia Armfield is a gothic, speculative reimagining of King Lear, following three estranged sisters—Isla, Irene, and Agnes—as they navigate grief, queer love, and the haunting weight of their past in a world that won’t stop drowning.

As they grapple with inheritance, trauma, and one another, the house he built—an architectural marvel on floodplains—becomes both a monument to his legacy and a battleground for their unresolved grief. Through alternating perspectives and a setting steeped in surreal disrepair, Private Rites examines what it means to carry the weight of the past in a world falling apart.

Summary

The story begins with Isla, a therapist whose measured exterior hides a constant struggle to maintain emotional control. While attending to a patient describing a childhood exorcism, Isla receives word of her father’s death.

She does not react with outward grief; instead, she slips into a clinical mode, contacting her sisters without processing her own emotions. Her detachment reveals itself in both her reaction to the news and the way she intellectualizes every aspect of her life, including her fractured relationship with her father.

Though she once tried to rebel by marrying someone he disapproved of, she never told him about her divorce, illustrating a deep-seated estrangement. Isla’s world, like the city around her, is on the verge of collapse.

Physically ill and emotionally stunted, she makes her way through the crumbling infrastructure toward the house her father left behind.

Irene, the middle sister, receives the call from Isla while commuting through a chaotic and overburdened city. She is numb, annoyed by the dissonance between how she thinks she should feel and how she actually does.

Formerly political and furious at the world, Irene now drowns her apathy in domesticity and disconnection. Her boyfriend Jude provides calm, though his presence also amplifies her sense of aimlessness.

Irene is quick to judge her sisters, especially Isla’s rigidity and Agnes’s aloofness, yet she’s also burdened by unresolved guilt. As she prepares to reunite with her sisters at their father’s home, she contemplates the emotional games he used to play—turning the girls against each other, offering affection conditionally, and always remaining a remote and critical presence.

Agnes, the youngest, is the most emotionally detached and physically estranged from the others. She works at a coffee shop and engages in anonymous erotic encounters, using her body as both shield and form of expression.

She ignores Isla’s messages for days, unwilling to confront the emotional weight the news brings. When she finally arrives at the hospital to view their father’s body, she chants to herself not to look, trying to avoid any confrontation with reality.

But ironically, she is the only one who does look directly at the corpse. Agnes’s memories are marked by being left out, ignored, and emotionally neglected by both her father and her half-sisters.

Even though they share blood, Agnes has always felt like a stranger in the family—an outsider whose existence reminds the others of their father’s betrayals.

The city they inhabit serves as a distorted mirror of their inner lives: relentless rain, flooding, decaying buildings, and failing infrastructure all signal collapse—not just ecological but emotional. Burial and transportation systems are crumbling, just as traditional expressions of grief and family unity are breaking down.

The house their father built—an engineering marvel that lifts itself above floodwaters—is as cold and clinical as he was, a structure more about control than comfort.

When all three sisters arrive at the house, tensions rapidly resurface. Isla, already strung out and emotionally frayed, tries to control everything—funeral arrangements, logistics, conversations.

Irene remains emotionally withdrawn, resorting to sarcasm and beer in the bath to cope. Agnes, unexpectedly arriving with Stephanie—a woman she has recently started seeing—brings a rupture.

Isla, drunk and bitter, is stunned by the presence of a stranger and furious over the fact that Agnes has inherited the house. For Isla, this is the ultimate betrayal, one last cruelty from their father that undermines her sense of order and legacy.

The sisters’ confrontation crescendos as Agnes accuses Isla and Irene of never truly seeing her pain, while Isla accuses Agnes of never being part of their shared suffering. Irene, in a sudden revelation, admits that she and Jude accepted money from their father, a hypocrisy that infuriates Isla and triggers her to slap Irene.

The reunion ends in collapse, both emotional and relational, and the sisters separate once more.

Months later, the emotional fallout continues. Jude, exhausted from their work as a social worker, reflects on the burden of care and the tenuousness of love in a disintegrating world.

Stephanie now lives with Agnes, who remains haunted by their mother’s absence and reappearance at the funeral. Agnes fears not just becoming like her father, but inheriting the parts of her mother she cannot remember but feels within her.

The notion of inheritance takes on a symbolic weight—not just property and money, but emotional templates, coping strategies, and legacies of pain.

In the story’s final sequence, the narrative shifts toward a surreal, apocalyptic tone. Rumors of a massive wave circulate through the city, symbolizing growing paranoia and myth-making in a place already falling apart.

Each sister continues to fragment emotionally, surrounded by environmental decay and social breakdown. Isla’s neighbor’s house collapses.

Irene begins to feel disconnected even from Jude. Agnes starts hearing strange voices and becomes increasingly paranoid.

Their tentative reconnection at the father’s house begins with shared meals, cautious conversation, and a brief moment of warmth. Agnes even decides she wants to share her future hopes with her sisters.

But the fragile calm is shattered by an intrusion. A group of strangers—some from Agnes’s past—arrive led by Caroline, a woman affiliated with a strange spiritual movement.

The visitors explain that Agnes has been chosen for “the Granting,” a ritual meant to restore balance. The cult’s presence reframes earlier events and childhood memories, including the disappearance of their mother, now revealed as tied to this long-standing occult belief.

The ritual becomes violent. Agnes is physically restrained, and a knife is drawn.

The ritualistic chanting begins. As the structure strains under the weight of the cultists and their ceremony, the house begins to collapse.

Rain bursts through windows. Chaos consumes the home.

In a final moment of sisterly solidarity, Isla and Irene dive into floodwaters to rescue Agnes. Isla is lost in the flood, possibly dead.

As the waters recede, snow begins to fall—an eerie, unnatural change from the endless rain.

The book closes with Irene and Agnes adrift in the ruins, unsure of what has happened, traumatized but alive. There is no reconciliation, no clean resolution.

What remains is a hard-won understanding of how grief, trauma, and legacy twist their way through families, shaping identity even after ties are broken. The narrative suggests that survival itself becomes a kind of ritual in a world where meaning is constantly eroded and rebuilt.

Characters

Isla

Isla, the eldest of the three sisters in Private Rites, is defined by her attempts at control, emotional repression, and professional detachment. As a therapist, she embodies the archetype of someone trained to navigate and analyze others’ trauma but is largely incapable of confronting her own.

Her reaction to the news of her father’s death is telling—not one of sorrow, but of procedural necessity, as she moves to inform her sisters almost mechanically. Isla’s relationship with their father, Stephen Carmichael, is fraught with intellectualized resentment.

He dismissed her both emotionally and professionally, yet she internalized his legacy through her obsession with order and analysis. The White Horse, the house he built, becomes both a symbol of her inheritance and a totem of his calculated, inhuman design.

Her grief is cerebral and she navigates it through task completion and routine—organizing funeral logistics, cleaning, and drinking with bitter precision. Isla’s brittle persona cracks in the presence of her sisters, particularly Agnes, whose rejection of sisterhood wounds her deeply.

Her sense of betrayal stems from the idea that Agnes escaped the same crucible of paternal control, though Agnes’s experience was equally, if not more, damaging. In a moment of desperate grief and confrontation, Isla lashes out physically at Irene, illustrating the degree to which her repression has curdled into rage.

Isla’s final act—rescuing Agnes during the cult’s invasion, only to vanish beneath the floodwaters—cements her as a character whose emotional immolation is the price of carrying the weight of her family’s dysfunction too long, too alone.

Irene

Irene, the middle sister, is the novel’s most emotionally volatile and politically disillusioned character, straddling the space between Isla’s rigidity and Agnes’s disengagement. Her coping mechanism is one of sarcastic detachment and occasional bursts of barely contained fury.

Once idealistic and politically active, Irene now floats in a sea of disillusionment, her past anger sublimated into cynicism and distance. Her relationship with Jude offers a modicum of stability, but even that is fraught with emotional silences and buried conflict.

Irene views her father’s death with ambivalence—not because she loved him, but because his absence fails to provoke the depth of reaction she expects from herself. Her resentment toward Isla is long-standing, rooted in the latter’s attempts to dominate the family’s emotional narrative.

Irene is caught in a pattern of passive complicity, having once accepted money from their father despite condemning such gestures in others. This duplicity reveals her discomfort with moral clarity and suggests a fractured sense of self.

Irene’s rage culminates during a confrontation with Isla, during which she is slapped—an act that serves as the eruption of years of buried tension. Yet, in the story’s climactic underwater chaos, she emerges not as a figure of bitterness, but of fierce survival.

Alongside Agnes, she clings to debris, devastated but alive, determined to carry on. Irene represents the part of grief that resists closure: the unwillingness to forgive, the pain of ambiguity, and the necessary friction between memory and endurance.

Agnes

Agnes, the youngest sister, is both the most estranged and the most emotionally raw figure in Private Rites. She grew up on the periphery of the family unit, a child of Stephen’s second chance at fatherhood and the mysterious woman who replaced Isla and Irene’s mother.

Her emotional and physical distance from her sisters fosters a profound sense of otherness that she wears like armor. Working in a coffee shop, drifting through erotic entanglements, and avoiding serious emotional introspection, Agnes represents a generation whose inheritance is not just fractured families but systemic collapse.

She avoids messages about her father’s death, dodges emotional commitments, and finds solace in the tactile and ephemeral—swimming pools, quiet intimacy, and the physicality of her relationship with Stephanie. Her detachment is not numbness but a defense against the overwhelming legacy of abuse, neglect, and manipulation.

When she is summoned back to the White Horse, Agnes initially maintains her emotional perimeter but begins to open herself in small, fragile gestures. Just as she seems ready to articulate her hopes to her sisters, she is violently thrust into the cultic ritual of “the Granting,” exposing the depth of generational trauma she carries.

Her near-sacrifice and subsequent rescue mark a symbolic rebirth: though she survives, she is forever altered. Agnes’s closing image—clinging to Irene amidst flood and snowfall—suggests a tentative reconnection and an unwilling yet undeniable step toward healing.

In her, the novel captures the ache of estrangement and the quiet power of choosing to survive when every structure, familial or societal, has failed.

Stephen Carmichael

Though deceased for much of the novel, Stephen Carmichael’s presence is an oppressive force that shapes the lives and psychologies of all three sisters. As an architect who designed the White Horse and other elite structures meant to evade the ecological collapse below, Stephen is both a literal and symbolic engineer of distance.

He built homes that elevated their occupants while emotionally disempowering their inhabitants. His form of parenting was authoritarian, manipulative, and coldly strategic.

He pitted his daughters against each other, using praise and punishment to sow division and confusion. To Isla, he was a standard to rebel against yet never truly escape.

To Irene, he was a master of psychological cruelty, always belittling her accomplishments while presenting himself as benevolent. To Agnes, he was both captor and ghost—an ever-present figure who rarely acknowledged her humanity.

His decision to leave the White Horse to Agnes further destabilizes the sisters’ dynamic, inflaming Isla’s sense of injustice and Irene’s feeling of marginalization. Stephen’s legacy is not just in architecture but in emotional architecture: the way he structured silence, hierarchy, and alienation into his family.

Even in death, he continues to manipulate them, leaving behind not just property but an emotional puzzle that poisons their reunion. His absence, paradoxically, is the most commanding presence in the novel.

Jude

Jude, Irene’s partner, operates as a stabilizing yet ultimately limited figure within the collapsing landscape of Private Rites. A social worker committed to a job that grows more grueling as society disintegrates, Jude represents the endurance of empathy in a world that increasingly devalues it.

Their love for Irene is steadfast, and they attempt to mediate tensions among the sisters during their gathering. However, Jude is also complicit in the family’s deception, having accepted hush money from Stephen alongside Irene.

This act introduces moral ambiguity into their otherwise gentle presence. Jude’s character underscores the burden placed on caregivers and the limits of kindness in the face of entrenched trauma.

Though often on the sidelines, Jude’s reflections—especially in the aftermath of the sisters’ fracture—provide a sobering lens through which we view the broader disintegration of societal and personal support structures.

Stephanie

Stephanie, Agnes’s lover, enters the story with a sense of quiet resilience and enigmatic strength. She becomes a point of contrast to the chaos of Agnes’s family, offering her a form of emotional sanctuary.

Yet Stephanie is also drawn into the dysfunction, attending the funeral and eventually living in the White Horse with Agnes. Her presence at key moments reflects the porous boundary between outsider and insider, and her acceptance of Agnes’s brokenness reveals a deep if precarious connection.

Stephanie does not claim to fix Agnes but remains present, even as the storm of inheritance and identity threatens to drown them both. In this, she symbolizes the potential for new forms of intimacy—ones not built on blood, obligation, or history, but on the willingness to remain when everything else is falling apart.

Themes

Emotional Estrangement and Inherited Dysfunction

In Private Rites, emotional estrangement between the three sisters is not merely the result of time or distance but the deeply rooted consequence of a dysfunctional family dynamic constructed and curated by their father, Stephen Carmichael. His manipulative parenting style, characterized by favoritism, psychological cruelty, and intentional divisiveness, shaped the sisters’ identities and set the course for their fragmented adult relationships.

Isla clings to the illusion of stability through structure and professionalism, yet her control mechanisms falter under emotional pressure. Irene embodies disillusionment, alternating between sharp sarcasm and emotional detachment, never quite able to process her bitterness into healing.

Agnes, left to weather her father’s abuse in near solitude, represents both the legacy of trauma and the difficulty of finding belonging in a family that never fully claimed her. These patterns of dysfunction are not easily severed with death; rather, the father’s passing sharpens their emotional injuries, forcing them to confront what they inherited not in terms of material wealth, but in psychological scarring.

The house he left behind—ingenious and soulless—becomes the physical symbol of this legacy, its flood-resistant architecture echoing the impermeability of emotional connection that defined their upbringing. As each sister navigates grief, they are also navigating the failure of family to provide safety, identity, or even basic affection.

The novel does not promise reconciliation or redemption, but instead emphasizes the complexity of surviving family not just biologically, but psychically, and the quiet devastation of recognizing that survival may be the most one can hope for.

Environmental Collapse as Emotional Landscape

The near-constant rain, flooding infrastructure, and crumbling cityscape in Private Rites do more than set the scene; they manifest the emotional condition of the characters. The environment, drowned and unrelenting, is an extension of the inner turmoil of Isla, Irene, and Agnes.

It is a world where systems have ceased to function, where public transport falters and burial customs break down, much like the sisters’ internal mechanisms for processing grief and loss. The collapsing physical world offers no comfort and reflects the instability of their shared and individual emotional terrains.

In this setting, grief does not have clean rituals, nor does it offer catharsis. Instead, it is something one has to navigate through debris—psychic, familial, and literal.

The rising waters that threaten the foundation of their father’s once-ingenious house mimic the emotional pressure mounting within each sister, as long-buried memories surface and long-repressed fears gain form. The eerie replacement of rain with snow at the novel’s end suggests not resolution, but a shift in the climate of loss, a cooling of emotion that may allow for survival but not necessarily healing.

Environmental decline becomes a metaphor for emotional disrepair, each influencing the other, so that to live in this world is to constantly confront both personal and planetary failure. In this way, the novel argues that personal dysfunction is not isolated from broader systemic collapse—it is all part of the same decaying fabric of existence.

The Architecture of Legacy and Control

The physical structure of the White Horse, the house designed by Stephen Carmichael, is the most tangible artifact of his legacy, and its design is a blueprint for how he treated people. Built to rise above the floods, it is a monument to resilience without warmth, protection without intimacy.

Its mechanical beauty is undeniable, yet within its walls lies a legacy of domination and emotional vacancy. Isla sees the house as an engineering marvel but emotionally dead, a metaphor for her father’s approach to parenting: brilliant but devoid of nurturing.

For Irene, it is a pressure chamber that stoked familial rivalries and exacerbated their mother’s descent into instability. For Agnes, who inherits it, the house is both burden and inheritance—what it offers in material terms, it denies in emotional continuity.

The house does not shelter; it traps. When outsiders later occupy it during the horrific cult sequence, the space reveals its true vulnerability.

It cannot defend against internal corruption or external invasion. As it collapses, it takes with it not just a structure, but the illusion of safety and permanence.

This failure underscores the idea that control—over water, over family, over memory—is illusory at best. The architecture that promised survival ends up nearly killing the very people it was meant to protect.

The house, like the father, leaves behind no moral foundation, only ruin. In the end, legacy is not what is built, but what is felt, endured, or fled from.

The Elusiveness of Grief and the Myth of Closure

Grief in Private Rites resists formality, structure, or even recognition. The sisters’ responses to their father’s death are not stages of healing but chaotic, contradictory waves of numbness, anger, guilt, and detachment.

Isla attempts to control her grief through alcohol, logistics, and performative stability. Irene intellectualizes and delays hers, masking unresolved trauma with cynicism.

Agnes sidesteps grief entirely, approaching it through physical avoidance and emotional compartmentalization. None of them cry in a conventional sense; none engage in rituals of mourning that offer communal solace.

Instead, grief is fragmented and solitary, mirroring their familial disunity. The intrusion of the cult and the collapse of the house disrupt any potential for structured memorialization, transforming the narrative from mourning to raw survival.

Closure is not offered because closure, in this world, is a myth—especially when what is mourned is not merely a person but a lifetime of neglect, cruelty, and manipulation. What each sister is really grieving is the possibility of a different past, one where love was unconditional and stability did not require engineering.

The narrative ends in ambiguity, with survival but not reconciliation, mourning but not forgiveness. This portrayal challenges the conventions of how loss is depicted in fiction, insisting instead that for many, grief is not about moving on but learning how to exist with what cannot be undone.

Sisterhood as Burden, Distance, and Reluctant Rescue

The relationship between Isla, Irene, and Agnes is not one of sisterly bonding but a volatile mixture of obligation, resentment, and reluctant care. They do not see each other as allies; they see each other as reminders of a past best forgotten or fought against.

Each sister has a competing narrative of suffering and survival, which makes empathy nearly impossible. Isla believes she carried the burden of responsibility.

Irene believes she endured their father’s cruelty in silence. Agnes believes she was abandoned to his worst impulses.

These perspectives clash violently, culminating in emotional outbursts and even physical violence. And yet, in the story’s most surreal and terrifying moment—when the cult threatens to sacrifice Agnes—it is her sisters who fight to save her.

This act is not a triumph of love, but a raw, instinctive response to the fear of permanent loss. The rescue is not celebrated; it is paid for with Isla’s disappearance, an unresolved wound.

The final scene—two sisters clinging to each other in a drowned world—is not a happy ending but a fragile truce. Sisterhood in Private Rites is a tether, not a balm.

It binds, even when there is no comfort in the binding. The novel does not romanticize familial bonds.

Instead, it portrays them as difficult inheritances in themselves—capable of destruction, but also of desperate acts of protection. It leaves open the question of whether these relationships can ever become more than what they were, or if enduring them is the best anyone can do.