Puck and Prejudice summary, Characters and Themes

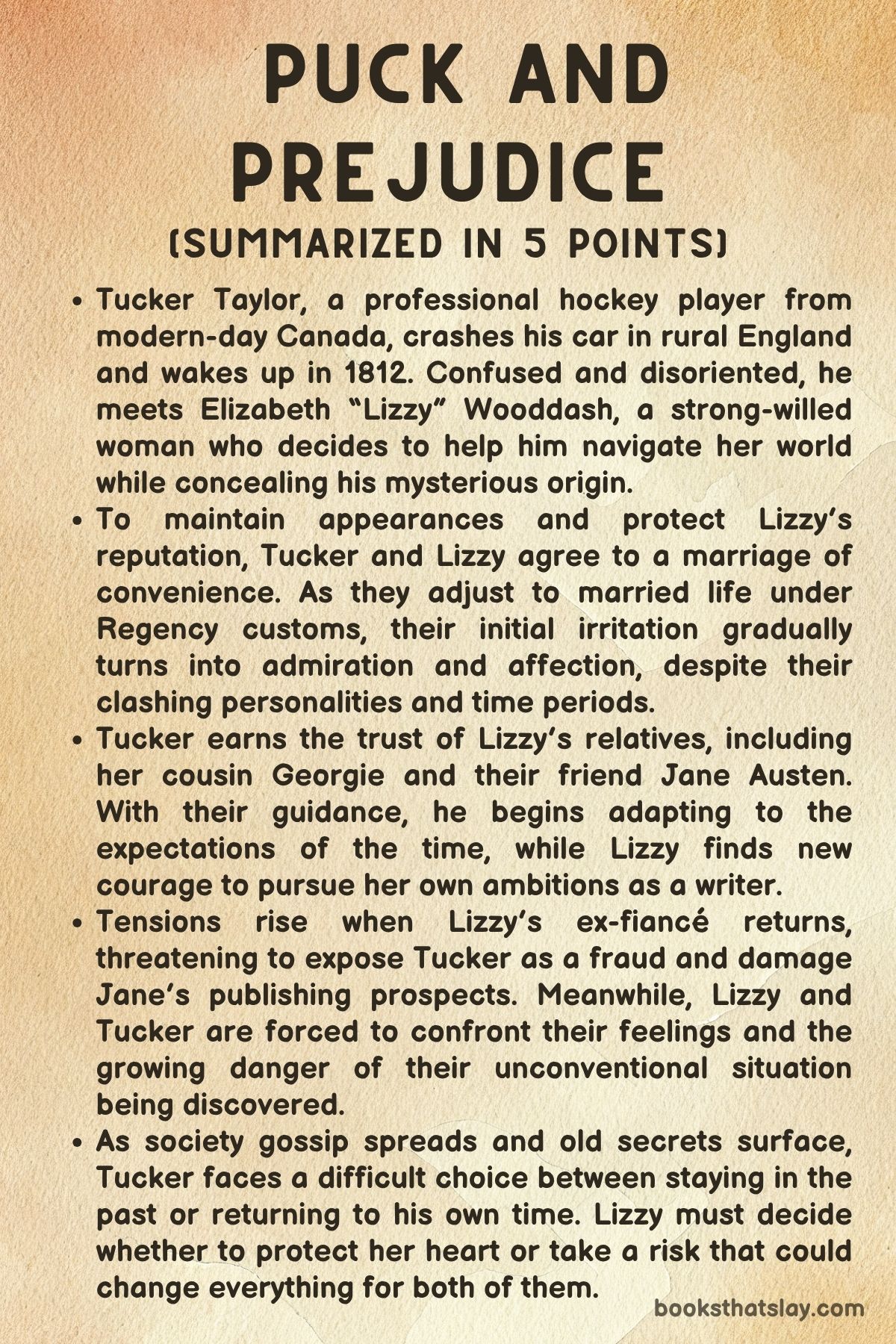

Puck and Prejudice by Lia Riley is a clever, heartfelt romance that imagines what might happen when a modern-day hockey goalie collides—quite literally—with Regency-era England. Combining the fast-paced charm of contemporary sports fiction with the formality and wit of historical romance, Riley brings together two unlikely souls: Tucker “Tuck” Taylor, a cancer-survivor-turned-time-traveler, and Elizabeth “Lizzy” Wooddash, a fiercely independent woman trapped by the expectations of her era.

Their story is both humorous and touching, filled with awkward social situations, cultural confusion, and simmering chemistry, all wrapped around a core of emotional growth, healing, and the liberating power of love that transcends time.

Summary

The story begins in the present day with Tucker Taylor, a professional hockey goalie whose career has recently been derailed by a battle with Hodgkin lymphoma. Seeking clarity and recovery, he travels to the English countryside, only to find himself swept into a surreal situation.

After swerving to avoid a child and dog on a frozen road, he crashes into a pond and awakens not in a hospital, but in 1812 England. His confusion is amplified when he encounters Elizabeth “Lizzy” Wooddash, a bold and sharp-witted woman in a lavender dress, who is just as bewildered by Tuck’s sudden appearance as he is by hers.

Lizzy, already burdened by familial expectations and the looming pressure to marry, quickly takes charge of the bizarre situation. She steals clothes from a nearby farm to help Tuck blend in and returns to him with a plan.

Tuck, still reeling from the loss of his modern identity, is thrust into a world of corsets, carriages, and strict societal rules. The tension between them simmers with a mix of attraction and antagonism.

As they make their way to Lizzy’s cousin Georgie’s estate, they face both the logistical hurdles of hiding Tuck’s origin and the emotional friction of two people with deeply different worldviews.

Once settled at the estate, Lizzy and Georgie introduce Tuck to an unexpected ally: Jane Austen. Though still relatively unknown, Jane is sharp, observant, and strangely accepting of Tuck’s time-traveling claims, especially after seeing his smartphone.

Together, the women construct a cover story to protect Tuck, posing him as a merchant from Baltimore. But in a time where women are expected to act as chaste brides-to-be and men to be honorable suitors, even this fabricated identity requires careful navigation.

To maintain appearances and protect Lizzy’s reputation, a solution is proposed: she should marry Tuck in a marriage of convenience. Lizzy balks at first, seeing marriage as an oppressive institution, yet Jane and Georgie present the idea as a form of liberation.

This arrangement would give Lizzy financial independence and shield her from her controlling brother Henry. Reluctantly, she agrees.

Tuck too is hesitant but understands the necessity. With awkward lessons in 19th-century manners and social norms, he begins to adjust, and through their shared predicament, he and Lizzy develop a rhythm built on sarcasm, curiosity, and an undercurrent of romantic tension.

As they journey to Gretna Green to formalize their marriage, their forced proximity ignites emotional and physical closeness. From clumsy cuddling in shared beds to Lizzy’s amusing purchase of a risqué book disguised as a horse breeding manual, their bond deepens.

Tuck becomes more attuned to Lizzy’s quiet strength and desire for autonomy, while she discovers in him a partner who sees her as an equal. Their connection grows, rooted in humor, respect, and mutual vulnerability.

Following their wedding, they begin a tentative new life as a married couple, although both are hesitant to call it real. Their honeymoon phase is quickly disrupted by the arrival of Lizzy’s brother Henry, who challenges Tuck to a duel, believing Lizzy has been compromised.

Lizzy firmly asserts her agency, publicly defying Henry and taking control of her own narrative. Later, during a walk, she breaks down emotionally, overwhelmed by the weight of years spent living under his thumb.

Tuck comforts her, but before their physical intimacy can progress, Lizzy falls ill with a fever.

Tuck, refusing to allow outdated and dangerous medical practices, stays by her side. When she recovers, he gently places a wedding ring on her finger—a quiet gesture that transforms their staged marriage into something more real.

They travel to London to face her family, where her mother decides they should attend a ball to publicly frame their union as a passionate love match. At the ball, Tuck encounters a shocking revelation: Ezekiel “Zeke” Fairweather, another time-traveler who has been living in the past for three years.

Zeke provides Tuck with an address for a secret meeting, confirming the surreal truth of Tuck’s condition and hinting at a potential way home.

While Tuck processes this new information, Lizzy navigates society’s pressures and expectations, including uncomfortable conversations about sex and marriage. After drinking too much and attempting to seduce Tuck, he respectfully declines, further affirming his commitment to her dignity and emotional safety.

Their romance now sits at a delicate crossroads: both are deeply in love, yet haunted by the looming decision of whether Tuck will return to his time or remain with Lizzy.

As their emotional intimacy intensifies, they eventually share a night of physical closeness, one defined by consent, tenderness, and trust. But the joy of their union is quickly overshadowed by loss when a family acquaintance, Frank Witt, dies suddenly, forcing Lizzy to confront the impermanence of love and the inevitability of grief.

She begins to question whether the happiness she’s found can truly last. Her fear of widowhood and loss deepens her desire to write, to immortalize not only her love for Tuck but the woman she has become.

When the opportunity to return to the future becomes real, Tuck makes the painful choice to go back, not out of selfishness, but out of respect for Lizzy’s agency. He does not ask her to come with him.

Lizzy, now more empowered and self-possessed, turns her sorrow into creative energy. She writes, finds her voice, and honors her feelings for Tuck without allowing them to consume her.

Eventually, she makes her own decision—to cross time for love, not out of desperation, but as a deliberate choice.

Lizzy’s arrival at one of Tuck’s hockey games in the modern era marks their reunion—not as fantasy, but as a new reality they are willing to create together. Their relationship evolves into a modern partnership that bridges time, built not on obligation, but mutual respect and support.

Tuck returns to hockey, and Lizzy, under the name E. H.

Wooddash, becomes a published author. Their lives continue on different tracks, yet always aligned, proving that love across centuries can not only survive, but thrive when it’s rooted in shared purpose and heartfelt connection.

Characters

Tucker “Tuck” Taylor

Tuck is a profoundly layered character whose identity evolves through hardship, humor, and love. A professional hockey goalie abruptly sidelined by a Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis, Tuck initially represents the archetype of the modern male athlete—resilient, competitive, and physical.

However, his sudden plunge into the past following a near-fatal accident peels away this façade, revealing a man grappling with lost purpose and forced vulnerability. In Puck and Prejudice, time travel becomes a metaphor for personal reinvention.

Thrust into 1812 with no roadmap, Tuck fumbles through cultural dissonance with a blend of sarcasm and sincerity. His awkwardness with chamber pots, outdated customs, and social mores creates comedic relief, yet his genuine attempts to adapt reflect humility and grit.

He respects Lizzy’s independence, never attempting to dominate her or diminish her intellect—qualities that set him apart from the men of her era and even many of his own. His past illness and dislocation from his sister Nora add emotional gravity, revealing his longing for family, stability, and belonging.

The slow-burning romance with Lizzy brings out his nurturing instincts and emotional depth, as he evolves from a man yearning for home into one willing to redefine it altogether. Through Tuck, the novel explores themes of masculinity, identity, and emotional authenticity in both contemporary and historical contexts.

Elizabeth “Lizzy” Wooddash

Lizzy is a fiercely intelligent and willful woman, defined as much by her resistance to societal expectations as by her yearning for personal authorship—both literal and metaphorical. Living in 1812, Lizzy faces the stifling constraints of a patriarchal world that demands marriage and obedience over intellectual freedom.

She is resourceful and quick-witted, qualities that allow her to navigate the initial chaos of Tuck’s arrival with remarkable composure and pragmatism. Her decision to steal clothes, create cover stories, and propose unconventional solutions reflects a survivalist brilliance masked by an acerbic tongue.

Yet beneath her surface defiance lies a profound insecurity, bred by a lifetime of suppression under her domineering brother Henry. Lizzy’s journey in Puck and Prejudice is one of incremental self-actualization.

Through her interactions with Tuck—who sees and treats her as an equal—she begins to challenge the internalized belief that her ambitions are foolish or futile. Her initial skepticism about love, particularly marriage, is gradually eroded by the tenderness and respect Tuck offers.

Her vulnerability, revealed in private confessions, moments of illness, and romantic uncertainty, never weakens her; instead, it amplifies her complexity. Lizzy becomes a symbol of transformation—not because she changes who she is, but because she finally embraces it.

Georgie

Georgie serves as Lizzy’s cousin and one of the more grounded figures in the story. She is pragmatic, socially adept, and plays a pivotal role in managing the logistics of Tuck’s presence in the past.

Her character is marked by a mix of concern and capability. She understands the stakes involved in harboring a time-traveler and uses her societal savvy to concoct plausible stories that protect Lizzy and Tuck.

Georgie’s encouragement of Lizzy’s independence, including support for the sham marriage, reveals her quiet rebellion against societal norms. Though she operates within the system, Georgie subtly subverts it by helping Lizzy take control of her own fate.

She is both a protector and a co-conspirator, representing the kind of allyship that doesn’t seek the spotlight but makes liberation possible. Her presence adds a stabilizing force to the narrative and underscores the importance of female solidarity in both resisting and navigating patriarchal structures.

Jane Austen

Jane Austen appears as both an historical figure and a literary touchstone within the novel. Her portrayal in Puck and Prejudice is clever and knowing—an author on the brink of greatness who intuitively understands the absurdities and constraints of her world.

Jane is calm and curious about Tuck’s situation, showing intellectual flexibility and empathy. Her reaction to the smartphone and her immediate grasp of its implications signal her as someone who, though bound by her time, sees beyond it.

Jane becomes a mirror for Lizzy’s aspirations and insecurities, particularly around authorship. She does not serve as a competitive benchmark but rather as an inspiring force who validates Lizzy’s talent and potential.

Her role, though secondary in plot, is central to theme—demonstrating how mentorship and belief from fellow women can ignite creative courage. Jane is more than a character; she is a symbol of permission and possibility for women who wish to write their own stories.

Henry Wooddash

Henry is Lizzy’s overbearing older brother and the embodiment of 19th-century patriarchal control. He believes he knows what’s best for Lizzy, exerting financial and emotional dominance over her life.

His rage at her unconventional marriage and attempts to duel Tuck reflect his obsession with honor and reputation, revealing a shallow understanding of family and affection. Yet his character is not without emotional depth.

When Lizzy falls ill, he allows Tuck to protect her, showing cracks in his rigid worldview. Still, his character exists primarily to heighten the contrast between control and freedom.

Henry’s suffocating presence sharpens Lizzy’s desire for autonomy and fuels her defiance. In this way, he functions more as an antagonist of ideology than of personality, reinforcing the societal obstacles Lizzy must overcome.

Ezekiel “Zeke” Fairweather

Zeke is a fascinating late-stage addition to the novel—a fellow time-traveler who confirms the supernatural reality of Tuck’s experience and opens the door to broader questions of fate, identity, and temporal displacement. He is mysterious yet friendly, offering vital information and the possibility of connection in an otherwise isolating experience.

His existence implies that Tuck is not alone, not crazy, and not the first. Though his role is brief, Zeke catalyzes a shift in the narrative’s scope: what was once a strange accident becomes part of a larger, perhaps unexplainable phenomenon.

Zeke represents the bridge between individual experience and collective mystery, between coincidence and design. His presence deepens the story’s magical realism and suggests that love, like time, may not be entirely linear or predictable.

Nora Taylor

Though she remains in the 21st century and appears mostly in Tuck’s memories, Nora casts a long emotional shadow over the narrative. She is Tuck’s younger sister and his primary anchor to the modern world.

Their bond, shaped by shared trauma and mutual care, adds emotional urgency to Tuck’s dilemma. He doesn’t just want to return home for himself; he wants to return to her.

Nora represents unfinished business, familial responsibility, and love in a different form. Her absence complicates Tuck’s growing feelings for Lizzy, creating an emotional tug-of-war between two worlds.

Though not physically present for most of the story, Nora’s significance lies in the moral gravity she provides, reminding Tuck—and the reader—that love comes in many forms, all of them powerful.

Themes

Identity and Self-Definition

Lizzy and Tuck are both characters struggling to maintain or rediscover a sense of identity in the face of overwhelming external pressures. Lizzy lives in a world where her future is presumed to revolve around marriage, domesticity, and silent acquiescence.

Her brother Henry treats her as a ward to be disposed of through marriage, and society expects her to abandon aspirations like writing. Yet she quietly resists, harboring dreams of authorship and independence.

Her encounter with Tuck allows her to see herself as more than a woman bound by Regency-era constraints—she begins to articulate her desires more forcefully and enact her own choices, whether it’s orchestrating a marriage of convenience or pursuing physical and emotional intimacy on her terms.

Tuck, conversely, is a man who has lost his professional identity due to illness and injury. As a hockey player, his sense of self was rooted in his physical prowess and public recognition.

The time-travel accident removes him from that framework entirely, forcing him to redefine himself in a world where no one knows his achievements and where he cannot perform the role he once did. His transformation from a reluctant stranger to a supportive, emotionally aware partner mirrors his internal reassembly—he learns to find value beyond his athleticism, embracing vulnerability, patience, and empathy as part of who he is.

Both characters ultimately forge new versions of themselves through their relationship, choosing self-definition over imposed roles.

Gender Roles and Autonomy

The narrative continuously critiques the rigid gender roles of 1812, positioning Lizzy’s resistance as both subtle and revolutionary. She exists in a system where a woman’s worth is tied to her marital prospects, dowry, and obedience.

Marriage threatens to subsume her identity legally and emotionally, and her brother’s control underscores how little agency women truly possess. Despite this, Lizzy refuses to accept a life dictated by others.

Her fake marriage to Tuck, while born of necessity, becomes an unlikely instrument of liberation, giving her access to resources and freedoms that would otherwise be denied.

Tuck’s presence, unbound by the expectations of the past, disrupts this hierarchy. He does not view Lizzy as property, nor does he seek to dominate her; instead, he respects her intellect and encourages her ambitions.

His refusal to consummate their marriage while she is intoxicated shows a deliberate rejection of the toxic masculinity of the era. Lizzy’s eventual control over her own sexual agency—buying a book to learn about intimacy, initiating a relationship on her own terms—marks a pivotal moment in reclaiming her body and desires.

Through these dynamics, the story explores how love and equality can only coexist when autonomy is honored, and how real partnership requires dismantling the roles society demands each gender perform.

Love Across Time and Space

The romance between Lizzy and Tuck is shaped by more than attraction—it’s defined by choice, risk, and mutual understanding. The time travel premise sets up a relationship that is fundamentally improbable, but what gives it weight is how the characters continuously choose each other despite uncertainty.

Tuck’s arrival upends both their lives, and instead of a magical resolution, the story builds tension around real emotional and temporal stakes. He might never return to his time; she may never leave hers.

Each act of affection, each compromise, is weighted with the knowledge that their time together may be finite.

Their bond grows not through grand gestures but through the steady accumulation of small ones: teaching each other, respecting boundaries, defending one another against family and societal pressures. Even when confronted with the chance to return home, Tuck never pressures Lizzy to follow.

That decision must be hers alone, an acknowledgment of the power of consent and independence within love. Lizzy’s eventual journey to the modern world is not portrayed as a sacrifice, but as an act of courage and clarity—she wants to be with him and have a life that spans centuries without surrendering who she is.

The love story, then, becomes a metaphor for overcoming the odds not with destiny, but with deliberate, compassionate choice.

Illness, Mortality, and Healing

Tuck’s battle with Hodgkin lymphoma and his near-death experience in the crash that sends him into the past establish illness and mortality as a quiet but significant undercurrent in the novel. His body carries the memory of a disease that nearly ended his life, and though it no longer visibly defines him, it informs how he sees the world.

Tuck approaches life with a cautious optimism and deep sensitivity, often emerging in moments where Lizzy struggles. His fear of losing her when she falls ill is immediate and desperate—echoing perhaps his own vulnerability when sick—and he rejects the barbaric treatments proposed in favor of protecting her with whatever modern knowledge he retains.

Lizzy, too, is not untouched by mortality. Frank Witt’s death throws her into emotional disarray, reminding her that happiness is not permanent and that love is not a shield against loss.

Her development is marked by the realization that the pursuit of passion—whether in writing or love—will always carry the risk of grief. Instead of letting this paralyze her, she accepts it as part of the human experience.

Tuck and Lizzy’s relationship then becomes one of mutual healing, not from disease alone, but from emotional scars: her stifled voice, his displaced identity. The healing they experience is imperfect but enduring, founded in the emotional honesty they offer each other.

Creative Ambition and Legacy

Lizzy’s creative drive is at the heart of her personal arc. Surrounded by women who either conform to society’s dictates or find clever ways around them, she struggles with the quiet fear that she will never be more than a would-be writer with no outlet.

Jane Austen’s presence in the story is a symbol of both inspiration and insecurity for her—Jane is the figure Lizzy dreams of becoming, but also a standard by which she doubts herself. Her internal refrain of “I’ll try” is a defense mechanism against failure.

Tuck challenges this with urgency and love, insisting she claim her voice with conviction.

Writing becomes more than a profession—it represents Lizzy’s desire to leave a mark, to narrate her own story in a world determined to silence her. Her journey toward becoming E.H. Wooddash, a published author, is a reclamation of both power and purpose.

The pseudonym preserves her independence while allowing her work to exist in a public domain. Her creative ambition, once a source of shame, is ultimately what leads her to build a life not only with Tuck but for herself.

Legacy, in this sense, is no longer about conforming to familial or societal expectations but about defining worth on her own terms. Through love, loss, and courage, she transforms her ambition into a tangible, enduring reality.