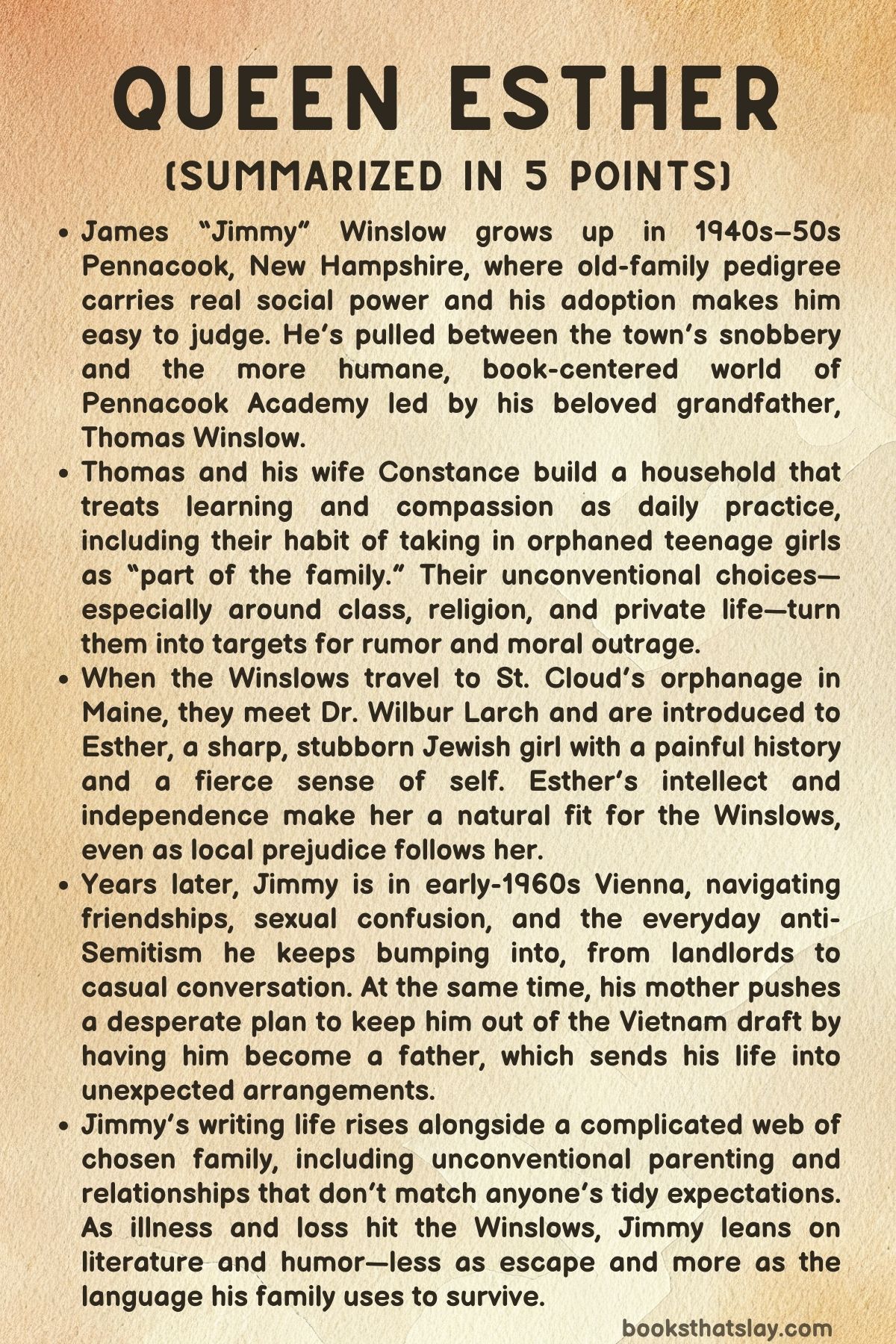

Queen Esther Summary, Characters and Themes

Queen Esther by John Irving is a family saga set against mid-century New England and postwar Europe, told through the lives of the Winslows and the adopted girl who changes them. In Pennacook, New Hampshire, bloodlines and reputation matter as much as money, and the Winslows’ habits—reading, teaching, taking in orphans, and refusing religious piety—make them local lightning rods.

At the center stands Esther: sharp, self-possessed, Jewish by history and memory, and determined to define herself on her own terms. Around her, Irving builds a story about belonging, courage, and the families people choose.

Summary

James “Jimmy” Winslow grows up in Pennacook, New Hampshire, in a town that measures people by ancestry and status. Jimmy’s problem is simple and permanent: he is adopted, with an unknown father and a mother who has no extended family to soften the mystery.

In a place where Mayflower names are social currency, he becomes the subject of constant gossip. Yet Jimmy’s home life is unusually stable because he is raised in the orbit of his grandparents, Thomas and Constance Winslow, whose standing protects him inside Pennacook Academy even as it draws suspicion from the town.

Thomas Winslow, a revered English teacher at the academy, believes literature is training for empathy. He is small, witty, and beloved by students, and he builds a household where books and moral arguments are daily nourishment.

Constance, a librarian from another old New England family, matches his certainty and keeps the family’s public face polished. They have three daughters named Faith, Hope, and Prudence, and then, after years, a surprise fourth child: Honor.

Thomas insists on that name because he wants more than goodness from his family; he wants a standard they must live up to.

The Winslows also take in orphaned teenage girls as live-in helpers, calling them “au pairs” and insisting they are part of the family rather than wards or foster children. The arrangement works: the girls thrive, excel in school, and stay connected long after leaving the house.

But their success makes Pennacook’s gossips even harsher. Neighbors treat the Winslows’ charity as a performance and look for scandal behind it.

Rumors grow, fed by the family’s Irish cleaning woman, about who sleeps where, why bedrooms shift, and why the household seems to ignore ordinary boundaries.

At the same time, the Winslows’ private beliefs bring them into open conflict with the town’s church culture. Thomas gives a public talk on the history of abortion in America, arguing that reproductive control existed long before modern politics turned it into a moral battleground.

When churchwomen challenge him about souls, Thomas refuses to concede faith as a civic requirement, and Constance bluntly rejects the idea outright. The room turns against them.

From that point on, Pennacook’s suspicion hardens into something close to hostility.

When their last trusted orphanage in New Hampshire shuts down under whispers of illegal abortions, Thomas and Constance look to Maine for another girl who can help in the home now that baby Honor has arrived. They contact Dr. Wilbur Larch, the physician who runs St. Cloud’s orphanage.

Larch is known for reading to children and for providing abortions despite public condemnation, and he tests the Winslows with pointed questions about money, motives, and religion. Their answers—education first, compassion as practice, faith as optional—match his own skepticism enough for him to invite them.

The trip to St. Cloud’s feels like stepping out of ordinary America. The station is empty, the road is muddy, and the orphanage buildings sit apart like a small, sealed world.

Inside, nurses guide the Winslows through the routines of children’s dormitories, a nursery, and delivery rooms that smell of ether and antiseptic. They also explain Larch’s private shame: a gonorrhea infection contracted during medical school, arranged by a father who treated sex like a rite of passage.

The illness and humiliation leave Larch celibate, obsessive about medicine, and reliant on ether to quiet his mind.

Larch recommends a specific child: Esther, fourteen, tall, and unusually composed. He tells them how she arrived years earlier, left on the porch on a snowy night by two women who announced, as if it were a warning, that the child was Jewish.

Esther, not frightened but furious, knew her name, her age, and a story she could recite with the authority of someone defending her identity. In Larch’s office, she told the biblical account of Queen Esther—how Esther and Mordecai saved their people from destruction—and explained that a rabbi had made sure she understood who she was.

Larch tried to place her with Jewish families, but without proof of her mother’s Jewishness, the community hesitated. Eventually, through synagogue records in Portland, a Reform rabbi helps trace Esther’s past: her mother Hanna Nacht, an immigrant from Vienna, widowed during the voyage when Esther’s father died at sea.

Hanna struggled as an English teacher in a hostile boardinghouse, harassed by anti-Semitic women. She left passports and the family story with a synagogue rabbi so her daughter would not be erased.

Soon after, Hanna was murdered, and the teenage babysitters who tried to bring Esther to the synagogue were tricked by impostors and led her, instead, to St. Cloud’s.

Esther grows up at the orphanage smart, stubborn, and unafraid of adult conflict. She reads constantly and claims her Jewishness as history and culture more than belief.

Her favorite line comes from Jane Eyre: “I care for myself… the more solitary, the more friendless, the more unsustained I am, the more I will respect myself.” The Winslows adopt her, and the orphanage mourns her departure. Even at the station, prejudice follows; a stationmaster sneers at the choice, but Esther meets it without flinching and teaches the Winslows not to confuse manners with decency.

Years pass, and Esther becomes a pillar of the Winslow household, especially for young Honor, who adores her strength. Esther studies Jewish history, Zionism, and languages with immigrant mentors, and she finds a surrogate Jewish family beyond Pennacook.

She becomes a nurse and plans a life of action rather than comfort. Honor and Esther make an intimate pact: one day Esther will have a child for Honor, and they will raise the baby together.

The Winslows accept the plan, not because it is easy, but because it fits the family’s belief that chosen bonds can be as real as blood.

In the early 1960s, Jimmy is studying in Vienna, living in a boarding apartment run by Frau Holzinger, her daughter Irmgard, and Irmgard’s son. Jimmy’s daily life is marked by odd conversations, cold rooms, and the sharp edge of European prejudice.

Irmgard toys with him in broken English and then, at a crucial moment, reveals she has been fluent all along. Jimmy also works with a German tutor, Annelies Eissler, a Jewish woman older than him, who uses intelligence, flirtation, and strategy to protect them both from the Holzingers’ hostility.

News of President Kennedy’s assassination hits Vienna like a shockwave, and Jimmy feels the strange loneliness of being the only American in a room where everyone turns toward him for meaning. He clings to his friends: Claude, a Frenchman, and Jolanda, a tall Dutch lesbian with a blunt sense of loyalty.

Their friendship becomes practical when they begin protecting a German shepherd, Hard Rain, from abuse. The dog turns into their shared project, their nightly vigil, and their proof that care can be active, not sentimental.

Jimmy’s mother, Honor, writes with a plan to keep him out of the Vietnam draft: he should become a father, because fatherhood might qualify him for exemption. The plan escalates into an arrangement in which Jimmy impregnates Mieke, Jolanda’s partner, so the two women can raise the child while Jimmy supplies biology, paperwork, and distance.

Jimmy travels to Amsterdam, faces skeptical parents, and enters a civil marriage designed to be undone later. The arrangement is awkward, public, and legally complicated, but it produces what they want: a child who will be loved without being trapped inside a standard template.

Back in New Hampshire, Jimmy returns to a family facing decline. Thomas suffers a stroke that leaves him paralyzed and unable to speak, and Constance slips into her own medical crisis.

Jimmy reads aloud from his developing novel, using language the way his grandfather taught him to: as company for the frightened and the lonely. Thomas responds with hand signals—thumbs up, thumbs down—still a teacher, still judging sentences and jokes even when the body fails.

Both grandparents die close together, and Jimmy’s reading becomes a last act of mutual recognition.

Afterward, Jimmy forms a quiet companionship with Alma, a nurse’s aide who listens to his work and, when gossip threatens, pretends to be his lover to neutralize rumors. Supported by the odd, imperfect kindness of the people around him, Jimmy finishes his education and commits to writing as his vocation.

In Amsterdam, Mieke gives birth to a baby girl, Vienna Winslow, raised by Jolanda and Mieke with Jimmy’s involvement and the Winslows’ complicated affection. Jimmy’s first major novel becomes a success, and his life settles into an unconventional balance: author, father, and witness to the way a family can stretch—through Esther’s example, through Honor’s schemes, and through Jimmy’s own willingness to let love take forms that the town of Pennacook would never approve.

Characters

James “Jimmy” Winslow

Jimmy is the emotional lens of Queen Esther, a young man shaped by a childhood spent straddling two worlds that don’t quite agree on his value: the status-obsessed town of Pennacook and the more intellectually generous Pennacook Academy. His adoption and unknown parentage make him permanently “explainable” to other people—an object of rumor—so he learns early to read social rooms like texts, always scanning for what’s being implied rather than said.

That sensitivity becomes both his wound and his gift: it feeds his insecurity and longing to belong, but it also becomes the foundation of his novelist’s eye, the instinct to notice contradictions, hidden motives, and the comedy that leaks out of human discomfort. As an adult abroad, Jimmy is still impressionable, still learning the difference between participating in other people’s plans and choosing his own life.

He’s pulled between genuine affection for the eccentric found-family around him and the humiliating reality that his mother’s schemes treat his body, his fertility, and his future as strategic tools. Even when he stumbles into farce—sex-as-policy, marriage-as-paperwork, the social chaos around “respectability”—he keeps returning to writing as the one place where he can tell the truth and create coherence.

By the end of his arc, Jimmy becomes a man who accepts unconventional love without needing it to look conventional, and a writer who finally turns his inherited empathy into art without letting the town’s old hierarchies define him.

Thomas Winslow

Thomas is the moral engine of the Winslow household and a quietly radical force in Pennacook, a man who uses literature not as ornament but as a training ground for empathy. His popularity and humor make him socially palatable even when his beliefs are not, yet his real defiance is domestic and philosophical: he believes in shaping souls through stories while refusing the town’s religious certainties about souls.

Thomas’s identity is inseparable from teaching; he treats young people—especially the vulnerable—as texts worth close reading rather than problems to be managed. His support of abortion access isn’t presented as mere politics but as an extension of his insistence on compassion over judgment and autonomy over sanctimony.

He’s also a paradox: public-facing warmth paired with private stubbornness, an idealist who genuinely believes he can build a better micro-society at home by taking in girls the world has discarded. In his decline, Thomas becomes an emblem of what his values cost and what they leave behind; even when he loses speech and independence, he remains present through comprehension, humor, and emotional responsiveness.

The way Jimmy reads to him near the end suggests that Thomas’s greatest legacy is not reputation or lineage but the habit of humane attention that he planted in others.

Constance Winslow

Constance represents old New England respectability, but she wields it in a way that both comforts and controls. She clings to the language of propriety—insisting the orphaned girls are “au pairs” and “part of the family”—as if the right phrasing can purify the messiness of need, class difference, and trauma.

That insistence can look like denial, yet it also reveals her strategy for resisting stigma: she refuses to let the town classify the girls as charity cases and refuses to let the girls internalize that label. Constance’s certainty is intimidating because it is so seamless; she doesn’t merely believe she is doing right, she believes the household’s order proves it.

At the same time, her blunt atheism exposes a steelier core than the town expects from a woman wearing the costume of gentility. She is protective, proud, and often uncompromising, and that combination fuels Pennacook’s suspicion: people sense that her goodness is not submissive goodness, and they don’t know how to forgive that.

Constance also embodies the novel’s tension between appearances and realities—she hates gossip yet helps provoke it by refusing the town’s “proper” boundaries around bodies, beds, and family roles. In the end, her decline alongside Thomas underscores how much the Winslow experiment depended on the force of her will and how deeply the family’s identity was built around the couple’s shared convictions.

Honor Winslow

Honor grows up as the “expectation,” a child named not for virtue but for a demanded standard, and that naming pressure shapes her into a person who turns ideals into action. She inherits the Winslow capacity for unconventional compassion, but she channels it less through teaching and more through designing radical forms of family.

Her bond with Esther becomes the defining relationship of her emotional life—part admiration, part longing, part political alignment—and it leads her to imagine motherhood outside heterosexual romance, outside the town’s moral math, and even outside biological necessity. Honor is also a strategist like her parents, but her strategies are intimate rather than civic; she tries to make a life that immunizes the people she loves against the world’s cruelty.

That desire can look selfish to outsiders, yet the story frames it as a response to the brutal contingencies of history and gender: if the world can steal children and futures, Honor will build a future that cannot be easily stolen. As Jimmy’s mother, she can be startlingly pragmatic, even manipulative, but the root of that pragmatism is fear—fear of losing her son to war, fear that chance will win unless she intervenes first.

Faith Winslow

Faith’s presence is shaped by the symbolism of her name and by the family’s public image: she belongs to a household that is constantly watched, evaluated, and misinterpreted. Rather than being defined primarily by personal plot, Faith functions as part of the Winslow chorus—evidence that the family’s ideals produced confident, educated daughters who unsettle Pennacook’s rigid expectations.

Even without extensive individual scenes, Faith matters because she embodies the town’s resentment: she benefits from an inherited name and status, but she also lives in a home that shares that privilege with outsiders, which makes her a living contradiction to the local hierarchy.

Hope Winslow

Hope operates similarly to Faith in the family constellation, but the resonance of her name intensifies how the town reads the Winslows as moral performers. In a community addicted to lineage, Hope represents the sort of future the Winslows keep insisting on: a future where care is not limited to bloodlines.

Her importance is less about private psychology and more about social optics—she is one of the “proofs” the Winslows offer that an educated, compassionate household can exist without religious authority, and that is precisely what enrages their neighbors.

Prudence Winslow

Prudence is the Winslow daughter whose profession turns her into the bridge between sentiment and clinical fact. As a doctor, she becomes the family’s translator of bodies—naming atrial fibrillation, explaining stroke damage, interpreting emotional lability—while the others are tempted to interpret suffering as morality or fate.

She is practical, direct, and often the adult in rooms where everyone else is coping through humor, nostalgia, or denial. Prudence’s steadiness does not make her cold; instead it shows how the Winslow style of compassion includes competence, not just kindness.

She also embodies the theme of women operating with authority in spaces where authority has historically been gendered male, a subtle echo of the earlier arguments about medicine, midwifery, and control over reproduction.

Gertie Eustis

Gertie is the unofficial loudspeaker of Pennacook’s resentments, a figure who converts private household quirks into public scandal. As the Irish cleaning woman, she occupies an in-between class position: she is inside the Winslow home but never truly of it, close enough to observe intimate details yet distant enough to weaponize them.

Her reports about sleeping arrangements and shared beds reveal how gossip functions as social policing, especially around bodies and sexuality. Gertie’s role is less about personal malice than about the town’s hunger to puncture the Winslows’ moral self-confidence; she provides the “evidence” people want so they can believe the family’s charity must hide something indecent.

Lucie

Lucie represents the Winslows’ earlier successes with taking in orphaned girls, which makes her a living argument against Pennacook’s cynicism. Her thriving—academically and socially—complicates the town’s preferred story that outsiders remain outsiders or that charity must be corrupt.

Even in brief mention, Lucie’s significance is that she proves the Winslows aren’t dabbling; they are building a pattern of belonging that persists beyond childhood and beyond the household walls.

Denise

Denise, like Lucie, is part of the evidence that the Winslows’ “family” is not symbolic but real. Her French-Canadian background and her origin in an institution tied to hidden abortions connect domestic care to broader social hypocrisy: the same society that shames unwed pregnancy also depends on discreet solutions.

Denise’s continued return to the Winslows signals that chosen family can be stronger than the town’s bloodline logic, which is exactly why the town finds her existence so irritating.

Dr. Wilbur Larch

Dr. Larch is a principled outsider whose authority comes from knowledge and labor rather than social pedigree. He runs St. Cloud’s with a stern tenderness: he reads to children, organizes their lives, and understands that care is never purely innocent when the world is brutal.

His pro-choice stance and his history with clandestine abortions position him as a moral realist; he sees what judgment does to women and what secrecy does to communities. Larch’s ether addiction complicates any attempt to turn him into a saint—his dependency is rooted in shame, bodily damage, and a twisted inheritance from a father who treated sex as initiation rather than intimacy.

That backstory makes Larch a character who understands how harm is transmitted across generations, often through supposedly “normal” male entitlement. In meeting the Winslows, he is both wary and hopeful: he wants Esther safe, but he refuses to hand her to people who merely want to feel virtuous.

He respects intellect and honesty, and his approval carries weight precisely because he knows how easily good intentions become exploitation.

Nurse Edna

Nurse Edna embodies institutional memory and the everyday bravery of care work. She is the one who physically finds Esther on the porch and emotionally registers the child’s rage rather than reducing it to misbehavior.

Edna’s responses show a profound respect for children as fully formed persons, even when they are frightened, furious, or inconvenient. She also represents the orphanage’s quiet feminism: a world run by women’s labor where survival depends on competence, collaboration, and the ability to keep moving despite grief.

Nurse Angela

Nurse Angela functions as both confidante and narrator within the St. Cloud’s ecosystem, the person who articulates what others might only imply. By discussing Larch’s past openly, she signals that this community has learned to survive through truth-telling rather than pretense.

Angela’s presence reinforces a major contrast in the novel: Pennacook trades in euphemism and gossip, while St. Cloud’s—despite its secrets—often deals in blunt realities because lives depend on it.

Esther

Esther is the novel’s central force of identity, resistance, and self-possession, a person who enters the story already refusing to be pitied. As a child, she arrives angry and articulate, holding on to her Jewishness as both inheritance and shield, and her retelling of the Queen Esther story becomes more than a lesson—it becomes her chosen framework for survival.

She grows into a woman whose strength can feel like armor, but it is not mere hardness; it is a disciplined refusal to let other people’s hatred define her. Esther’s skepticism toward religion is not a rejection of belonging but a choice to separate culture and history from metaphysical consolation, which makes her faithfulness to Jewish identity feel deliberate rather than inherited.

Her passion for literature, especially the self-respecting solitude of her favorite Jane Eyre line, reveals a core ethic: dignity is not granted by family or society; it is claimed. In the Winslow household, Esther becomes both family member and catalyst, deepening their defiance while also protecting them with her clarity about bigotry.

Her later commitment to Zionism and resistance work extends her personal story into political history; she moves from being “the Jewish one” singled out at a station platform to someone who chooses the front lines of Jewish survival. The pact with Honor, in which Esther agrees to bear a child for her, shows how Esther’s fierce autonomy can coexist with radical intimacy: she does not surrender her body to expectation, but she can choose to offer it as love, solidarity, and continuity.

Hanna Nacht

Hanna is a haunting presence whose life explains why Esther’s identity is so fiercely guarded. As a widowed immigrant and English teacher, she occupies a precarious social position—educated enough to be threatening, foreign enough to be targeted, and Jewish in a world that demands concealment.

Her determination that Esther “know who she is” becomes her final act of mothering, a refusal to let violence erase lineage. Hanna’s murder is not just tragedy; it is the story’s indictment of ordinary, domestic anti-Semitism, the kind that hides in boardinghouses and laundry rooms rather than uniforms and rallies.

Simon Nacht

Simon’s role is brief but symbolically heavy: he represents the fragility of immigrant dreams and the randomness that can reshape a family’s fate. His death en route to America turns Hanna into a single mother in hostile circumstances and makes Esther’s origin story one of loss before she can even remember it.

In that sense, Simon becomes part of the novel’s larger meditation on how history steals futures quietly, long before anyone calls it catastrophe.

Rabbi Leopold Herzfeld

Rabbi Herzfeld serves as the archivist of truth in a world of erased records and convenient doubts. His ability to trace Hanna’s story through synagogue documentation highlights how identity can depend on paperwork when communities are afraid to risk belonging on trust alone.

He embodies both the strengths and limits of institutional memory: he can recover the passports and the narrative, but he cannot undo the fact that Esther was refused by families who feared uncertainty. In doing so, he becomes a gentle critique of communal caution, even as he is also the reason Esther’s history is not lost.

Mrs. Sweeney

Mrs. Sweeney is Pennacook’s organized moral outrage, the kind that weaponizes spirituality against complexity. She confronts Thomas not as an individual but as a representative of a threatening worldview, and her certainty about fetal souls illustrates how belief becomes power when it is used to police others.

She is not portrayed as nuanced so much as illustrative: she is the face of the town’s need to punish anyone who refuses its religious monopoly on “goodness.”

Frau Holzinger

Frau Holzinger embodies a domestic authoritarianism that mirrors larger political histories without naming them directly. As Jimmy’s landlady, she controls heat, space, and atmosphere—small tyrannies that matter intensely in winter and in loneliness.

Her household feels like a museum of old resentments, where hospitality is conditional and surveillance is constant. She shows Jimmy that prejudice can be baked into everyday arrangements, not just slogans.

Irmgard Holzinger

Irmgard is one of the most psychologically slippery characters, a woman who uses performance as both flirtation and defense. Her broken English is revealed as an act, and that revelation reframes everything about her earlier intimacy with Jimmy: what seemed like awkward vulnerability becomes controlled experimentation, even manipulation.

Irmgard’s sensuality is strangely detached, as if physical closeness is safer than emotional truth, and her anti-Jewish comments expose a moral ugliness beneath the erotic ambiguity. She is also deeply melancholic, suggesting a life shaped by secrets and compromises, and her ability to switch masks instantly makes her feel like a private allegory of postwar Europe: charm on the surface, buried violence and denial underneath.

Siegfried

Siegfried is eerie not because he is supernatural but because he feels like a child trained by a warped environment. Living in the Holzinger household, he absorbs its atmospheres—secrecy, hostility, and a fixation on symbols like photographs.

His showing the old image of Irmgard with a German shepherd ties the present to the past in a way that implies inheritance of behavior as well as blood. He functions as an unsettling reminder that families transmit values even when they pretend they are only transmitting manners.

Fräulein Annelies Eissler

Annelies is one of Jimmy’s most formative adult relationships because she refuses to let him stay passive. Intelligent, Jewish, older, and sharper than his romantic fantasies, she uses language instruction as a way to teach him agency, forcing him to repeat, correct, and become “more comfortable” not just in German but in himself.

Her flirtation is not merely seduction; it’s a controlled test of boundaries, a way to see whether Jimmy can handle desire without collapsing into embarrassment or surrender. Annelies also understands the social physics of prejudice and uses clever theater—climbing into his bed as cover—to blunt the Holzingers’ hostility.

In doing so, she becomes both protector and truth-teller, warning Jimmy that he cannot manage life through avoidance, postcards, or other people’s plans. She is the character who most directly challenges his belief that fate is something that happens to him, insisting instead that he must choose, act, and accept consequences.

Claude

Claude is comic relief with real emotional stakes, a friend whose flamboyant anxiety and romantic longing highlight how love can be both ridiculous and sincere. His obsession with details—imagined deformities, impossible scenarios—makes him funny, but beneath the humor is a deep vulnerability: he wants Chantal, wants certainty, and cannot bear being cast as secondary in someone else’s scheme.

Claude’s loyalty to Jimmy persists through embarrassment and chaos, and his later marriage suggests that even the most farcical social entanglements can eventually settle into tenderness.

Jolanda

Jolanda is a disruptive stabilizer: she creates noise, provokes scenes, teases mercilessly, and yet becomes the most reliable guardian in the group. As a tall Dutch lesbian who refuses to apologize for taking up space, she stands in contrast to Jimmy’s habitual self-consciousness.

Jolanda’s love is practical—she protects Hard Rain, navigates parents, organizes crises—and her humor often functions as a weapon against shame. She also models a way of building family through intention rather than permission, insisting that pregnancy, marriage, and parenting can be rearranged to fit the people involved rather than society’s script.

Her fierceness is the emotional infrastructure that holds the unconventional family together.

Mieke

Mieke is defined by consent and authorship—over her body, her relationships, and her art. Choosing to become pregnant by Jimmy within a lesbian partnership is not framed as confusion but as a deliberate design for family.

She holds a quiet strength that complements Jolanda’s loudness: Mieke can endure social scrutiny, navigate legal complications, and keep affection intact even when the arrangement looks absurd to outsiders. Her later emergence as a novelist mirrors Jimmy’s, suggesting that creativity in this world is not separate from how people live; it is another method of shaping reality.

Mieke’s pregnancy and motherhood become acts of collaboration rather than ownership, and her relationship with Jimmy remains tender without pretending to be conventional romance.

Chantal

Chantal is less a fully visible person in the summary than a gravitational object around which other people’s desires, jealousies, and strategies spin. Being designated as the “solution” to Jimmy’s draft problem reduces her to a role, which reveals how easily women’s bodies are treated as instruments in male political systems and maternal scheming.

The intensity of Claude’s feelings for her also shows how a person can be loved not only as who they are, but as what they represent—hope, escape, legitimacy.

Dagmar

Dagmar is quiet authority, a widow whose sadness does not prevent decisiveness. As the manager of the Kaffeehaus Nachtmusik, she presides over a space where history, music, and routine loop endlessly, and her delivery of Kennedy’s death lands like a communal rupture.

Dagmar’s moral clarity shows most powerfully in her protection of Hard Rain: she fires Hildegund for cruelty and makes a home for the dog despite her own preferences. She represents a kind of secular ethics—do what is right, not what is comfortable—that echoes the Winslows’ values in a different key.

Hildegund

Hildegund is volatility and damaged aggression, a person who channels her own experience of abuse into the abuse of someone weaker. Her tattooed toughness and romantic appeal to Jolanda conceal a capacity for cruelty that eventually becomes undeniable.

Hildegund’s arc illustrates how charisma can distract from harm and how love does not redeem someone who refuses responsibility. Her final loss of Hard Rain is a moral consequence rather than a melodramatic punishment; it’s the story insisting that care is proven by behavior, not by neediness or a tragic backstory.

Hard Rain

Hard Rain is more than a pet; she is a shared moral project and a symbol of chosen responsibility. The students’ rotating care—sleeping with her, hiding her, protecting her—becomes a rehearsal for the cooperative parenting and unconventional family structures they’re building among themselves.

The dog’s vulnerability exposes the characters’ deepest instincts: Jolanda’s protectiveness, Dagmar’s justice, Hildegund’s cruelty, and Jimmy’s capacity to commit to care even when he feels powerless elsewhere.

Els

Els, Jolanda’s mother, is the voice of parental control and social legitimacy, a woman who measures life by propriety and legal clarity. Her disapproval is not mere villainy; it’s fear translated into rules, the terror that an unconventional plan will harm her daughter or create permanent disorder.

Even so, her willingness to engage the plan at all suggests that love can bend, grudgingly, toward acceptance when faced with a reality that won’t be shamed out of existence.

Jeroen

Jeroen, Jolanda’s father, is mild where Els is strict, a man who embodies reluctant compromise. He represents the quieter form of parental love that tries to keep peace without becoming morally theatrical.

His presence helps show that not all resistance to unconventional family is ideological hatred; sometimes it’s simple bewilderment, softened by affection.

Bente

Bente, Mieke’s mother, is overtly sensual and emotionally demonstrative, a character who collapses boundaries with touch and gratitude. She treats Jimmy less like a son-in-law figure and more like a catalytic ingredient in a family miracle, thanking him for pregnancy as if it were a gift delivered on request.

Her flirtation can feel intrusive, but it also suggests a household where bodies and intimacy are less policed than in Pennacook, reinforcing the theme that “proper” behavior is culturally relative and often performative.

Moshe “Little Mountain” Kleinberg

Moshe is physical strength paired with historical vulnerability, a Jewish wrestler whose body is both weapon and target. His love story with Esther is grounded in shared identity and shared danger; they are drawn together not only by attraction but by the knowledge that history is closing in.

Moshe’s emigration to Haifa places him within the larger movement of survival and nation-building, and his role in Esther’s planned motherhood for Honor makes him part of an unconventional lineage: fatherhood not as possession, but as contribution to a community-defined future.

Reva

Reva functions as family anchor and continuity, the older relative whose presence connects personal love stories to collective migration. Her move with Moshe to Haifa emphasizes the intergenerational nature of displacement and rebuilding.

She also highlights that Esther’s life in this phase is not romantic adventure alone—it is logistics, settlement, caregiving, and the daily work of making safety real.

Alma

Alma is a caretaker who becomes a companion, a woman whose gentleness carries its own quiet rebellion. As a Mexican American nurse’s aide, she occupies a socially vulnerable position in the Winslows’ world, and that vulnerability makes her both a target for gossip and a mirror for the family’s claims about equality.

Her relationship with Jimmy is built on mutual usefulness—she comforts, he reads—but it grows into something more intimate in its trust and steadiness. Alma’s refusal of religious life and motherhood reframes the novel’s conversations about women’s choices: she is not defined by sacrifice, and her care is not a substitute for her own desires.

By “pretending” to be Jimmy’s lover to manage gossip, she exposes how much of social morality is theater, and she chooses to control the script rather than be punished by it.

President John F. Kennedy

Kennedy appears not as an intimate character but as a historical shockwave that exposes national identity in a foreign room. The café turning toward Jimmy after the assassination underscores how Americans abroad can become representatives of their country whether they want to be or not, and how public tragedy collapses private drama into sudden perspective.

Themes

Lineage, legitimacy, and the politics of belonging

In Queen Esther, identity is treated less as a private truth and more as a public verdict issued by communities that think they own the right to define someone. Jimmy grows up in Pennacook with a name that carries Mayflower prestige, yet his adoption turns that prestige into a question mark.

The town’s obsession with bloodlines makes him both visible and unknowable: he can be pointed at, categorized, and gossiped about, but never fully placed. That tension exposes how “belonging” in Pennacook is not earned through character so much as assigned through ancestry.

The academy complicates this logic by offering a different yardstick—intellect, wit, and the ability to read the world with some generosity—so Jimmy becomes two versions of himself depending on who is judging. The resulting split isn’t just social; it shapes how he narrates his own life, how he measures what he deserves, and how he decides whether love is stable or conditional.

Esther’s story sharpens the theme by showing a second kind of contested legitimacy: not whether she is “good enough,” but whether her identity can be verified. She arrives with certainty about her name and her Jewishness, yet adults around her treat that certainty as insufficient without paperwork.

The refusal of families to adopt her because documentation is missing is a devastating comment on how institutions convert human reality into administrative proof, and how fear can hide behind procedure. Meanwhile, the Winslows offer an alternative model of belonging: family as an act of recognition rather than an act of verification.

Still, even that model isn’t free of pressure, because Pennacook reads their choices as provocation. When Esther later commits herself to Jewish history, languages, and Zionism, it becomes clear that belonging is not a single acceptance but a series of decisions—some chosen, some forced—about where one’s name, body, and loyalties will be allowed to rest without explanation.

Chosen family, caregiving, and the ethics of taking people in

The Winslow household runs on a radical premise for its setting: family can be expanded deliberately, not only through birth but through responsibility. Constance insists the orphaned girls are “part of the family,” refusing labels that might admit hierarchy.

Yet the very insistence reveals the social risk: in a town that treats charity as performance and lineage as a gate, taking in orphans looks like either arrogance or disguise. The Winslows are not naïve about the suspicion; they accept the cost because they believe a home can be a corrective to the randomness of abandonment.

At the same time, the narrative doesn’t allow the reader to treat this as uncomplicated goodness. The system depends on power—who gets chosen, who gets trained into middle-class success, whose pain is translated into Winslow ideals.

Even if the results are nurturing, the arrangement can still resemble a social experiment in the eyes of outsiders because the Winslows control the terms.

Esther’s adoption makes the stakes more intimate. She is not presented as a passive recipient of rescue; she’s strong, angry, and self-defining.

That matters because it shifts the moral center of caregiving away from the savior’s self-image and toward the adopted person’s autonomy. The Winslows may bring her into their home, but Esther brings her own intellectual hunger, cultural memory, and fierce self-respect, and those qualities end up protecting the family as much as the family protects her.

The pact between Esther and Honor—planning a child raised by two mothers—pushes chosen family from household practice into intentional design. It treats caregiving as something you can plan cooperatively rather than inherit automatically.

Later, caregiving returns in a different form when Jimmy reads to his grandparents in their final decline and when Alma becomes his steady companion during his writing. Care becomes a language: reading aloud, tending bodies, sharing silence, absorbing gossip without letting it dictate what the relationship must be called.

Across these relationships, Queen Esther argues that family is not merely who shares your blood or your name; it is who stays present when the body fails, when the town whispers, when institutions refuse you, and when love needs to be expressed through ordinary acts rather than public declarations.

Social class, reputation, and the violence of gossip

Pennacook’s social order operates like a court that never adjourns. People are ranked, tried, and sentenced through rumor, and the currency is not evidence but plausibility shaped by prejudice.

Jimmy’s uncertain parentage becomes a permanent invitation for speculation. The Winslows’ prestige should protect them, yet their behavior—reading habits, moral confidence, and refusal to submit to local religious authority—turns prestige into a target.

Gossip becomes a tool that polices deviation: the town does not need to prove wrongdoing; it only needs to hint that something “improper” must be happening behind the Winslows’ domestic openness. Even the children’s sleeping arrangements and the placement of bedrooms are treated as moral clues, as if architecture were a confession.

What makes this theme powerful is that gossip is shown as both petty and destructive. It isn’t merely background noise; it shapes the limits of what people can safely do.

The Winslows’ charitable choices are read as public theatre, and the town’s resentment reveals a fear of being judged by higher standards. Their neighbors translate generosity into accusation because accusation restores equality: if the Winslows can be suspected, then their difference no longer threatens the town’s self-image.

The stationmaster’s sneer at Esther—reducing her to “the Jewish one”—shows gossip’s harsher cousin: open contempt that the community permits because it matches existing hierarchies. His shouted announcement is a public branding, meant to follow Esther even as she leaves.

This social surveillance is echoed later in Vienna, where Jimmy faces a different but related form of judgment. The Holzingers’ hostility, Irmgard’s anti-Semitic undertones, and the institutional scrutiny around Fräulein Eissler’s visits reveal how quickly private life becomes subject to interpretation when a community wants a scapegoat.

Even Alma and Jimmy’s companionship attracts speculation at home, demonstrating that gossip is not limited to a single place; it is a recurring method for enforcing norms about sex, age, and propriety.

Across these settings, Queen Esther treats reputation as something a community claims ownership over. People are rarely allowed to be simply complicated; they must be categorized into the acceptable or the suspicious.

The harm is cumulative: it narrows the kinds of care people can offer, the kinds of families they can build, and the kinds of truths they can speak without being punished by the story others choose to tell.

Secular morality, bodily autonomy, and the struggle over reproductive control

The conflict around abortion in Queen Esther is not staged as an abstract debate; it is embedded in the social mechanisms that decide whose bodies are regulated and whose beliefs become law. Thomas’s public talk on abortion history is a direct challenge to Pennacook’s moral authority structures.

By framing abortion as something that existed openly in earlier America and was later criminalized through professional power plays, he shifts the discussion from “sin” to control—who gains authority over reproduction, who loses it, and how religious certainty can be recruited to justify that transfer. The hostile reaction from churchwomen and the outrage at Constance’s blunt atheism reveal the fragility of communal righteousness: the town is less disturbed by the complexity of the issue than by the Winslows’ refusal to accept that a single moral vocabulary must govern everyone.

St. Cloud’s makes the theme tangible. The orphanage exists in the shadow of unwanted pregnancies and social punishment, and Dr. Larch’s medical practice is shown as a response to reality rather than ideology.

The closure of the Berlin institution rumored to be connected to secret abortions hints at the dangerous consequences of forcing reproductive decisions underground. Larch’s skepticism toward religion and his devotion to the orphans position him as someone who measures morality by outcomes: fewer ruined lives, fewer desperate acts, more honesty about what people will do when cornered.

His ether addiction adds another layer, suggesting how personal damage and shame can distort even a life dedicated to care, and how “purity” narratives often ignore the real costs of human frailty.

Honor’s later plan to protect Jimmy from the draft by having him become a father introduces a different dimension of reproductive politics: parenthood as legal strategy. The idea is comic on the surface, but it exposes how institutions create incentives that turn bodies and pregnancies into paperwork solutions.

The Amsterdam arrangement—Mieke and Jolanda raising a child with Jimmy’s biological contribution—turns reproduction into a negotiated project rather than a default moral script. That negotiation is not portrayed as cold; it is portrayed as practical, loving, and shaped by the pressures of law, war, and social expectations.

Throughout Queen Esther, the body is where ideology tries to become policy. The narrative consistently favors decisions made with awareness, consent, and responsibility over decisions demanded by dogma or by public performance.

It also shows that autonomy is never purely personal; it is constantly bargained for against governments, churches, and towns that believe their rules should reach into private life.

Jewish identity, antisemitism, and cultural survival without guaranteed refuge

Esther’s arrival at St. Cloud’s begins with a sentence shouted in the dark—“She’s Jewish!”—and that moment frames Jewishness as both identity and accusation. The child’s own steadiness contrasts with the adult world’s instability: she knows who she is, but the world around her treats that knowledge as a problem to solve or a risk to avoid.

The failed attempts to place her with Jewish families because her maternal status cannot be documented expose how vulnerable identity becomes when it depends on communal gatekeeping and fear. The refusals are not framed as cruelty alone; they are framed as caution shaped by history, yet the effect is still abandonment repeated under a different rationale.

The later discovery of her mother’s story—harassment, pressure to hide, and eventual murder—places antisemitism not in the realm of casual insult but in the realm of lethal social permission. Hanna Nacht’s determination that her daughter will know she is Jewish becomes a final act of resistance against a society trying to erase her.

Esther’s adulthood demonstrates a form of survival built on culture, learning, and commitment rather than piety. She identifies as Jewish culturally and historically even while doubting God, which challenges the simplistic assumption that identity must be religious to be real.

Her attraction to Jane Eyre and her desire to tattoo a declaration of self-respect capture how she constructs strength from texts and personal creed when institutions fail. The stationmaster’s contempt at the train platform shows how antisemitism can be crude and loud, but Esther’s response—calm, unsentimental, refusing fear—shows a survival strategy that does not depend on winning the approval of the hateful.

Her movement toward Zionism, language study, and eventual work connected to resistance and Palestine situates Jewish identity within the 20th-century search for safety and agency. The relationship with Moshe and the plan to bear a child for Honor carry both tenderness and symbolism: continuity of Jewish life paired with the Winslow experiment in chosen family.

Yet the narrative does not present “a homeland” as a simple resolution. It presents displacement, war, and competing forces as ongoing conditions, suggesting that refuge is rarely complete and that identity can remain contested even when one is surrounded by one’s people.

In Jimmy’s Vienna storyline, antisemitism appears again in domestic, almost casual forms—Irmgard’s hostility, the atmosphere that makes Fräulein Eissler’s presence strategic rather than safe—reminding the reader that prejudice persists as a daily environment, not just a historical event. Queen Esther treats Jewish identity as something carried through story, language, memory, and chosen loyalties, sustained even when recognition is withheld and safety is never guaranteed.

Literature as moral education and as a method of making a life

Books in Queen Esther are not decorative; they are instruments of formation. Thomas Winslow teaches empathy through literature, and his classroom values humor and intellect as ways to expand what students can feel for other people.

This matters in a town that measures worth through ancestry and conformity, because literature becomes a rival authority: it suggests that understanding can be learned, and that moral imagination should not be inherited only from family or church. The Winslows’ habit of reading is interpreted by neighbors as showing off, but the narrative frames it as a daily practice that builds inner life and resists small-minded certainty.

Esther’s reading takes this further. She latches onto Jane Eyre not as escapism but as a manual for self-respect.

The quoted line she repeats is a statement of survival philosophy, especially for someone raised in an institution that could not guarantee a future. Her relationship to text is intimate and bodily—she wants the words marked on her skin—showing how literature can become a substitute for stable lineage, a portable inheritance when family history is stolen or disputed.

Dr. Larch reading to orphans places literature in the space where care happens. Stories become a kind of shelter, a routine that tells children they are worth attention and that their minds matter even when society labels them unwanted.

Jimmy’s evolution into a novelist makes the theme explicit: writing becomes how he metabolizes experience, grief, and the oddness of his family. On the train he reads Anna Karenina, and his reading life blends into his writing life, suggesting that the boundary between consuming stories and producing them is thin when a person is trying to make sense of who they are.

When he reads his draft of The Dickens Man aloud to his grandparents, literature turns into a bridge across disability and approaching death. Thomas’s thumbs-up and thumbs-down are a form of editorial dialogue when speech is gone, implying that the teacher who shaped others through books remains a reader who can still respond, judge, and recognize humor.

The comic misunderstanding of “labile” and “labia” matters thematically because it shows literature and language as something living—capable of tenderness, embarrassment, and laughter even in a room full of decline. Alma’s role as listener later reinforces that art is sustained by audience and companionship.

She helps him keep working not through critique but through presence and attention, the same kind of attention Dr. Larch gives the orphans and Thomas gives his students.

Across Queen Esther, literature is presented as a moral technology: it trains empathy, supplies self-definition, creates continuity when families fracture, and offers a way to speak when ordinary speech fails. It is also shown as a craft that can turn private chaos into public meaning without asking permission from the town’s standards.