Quietly Hostile Summary, Analysis and Themes

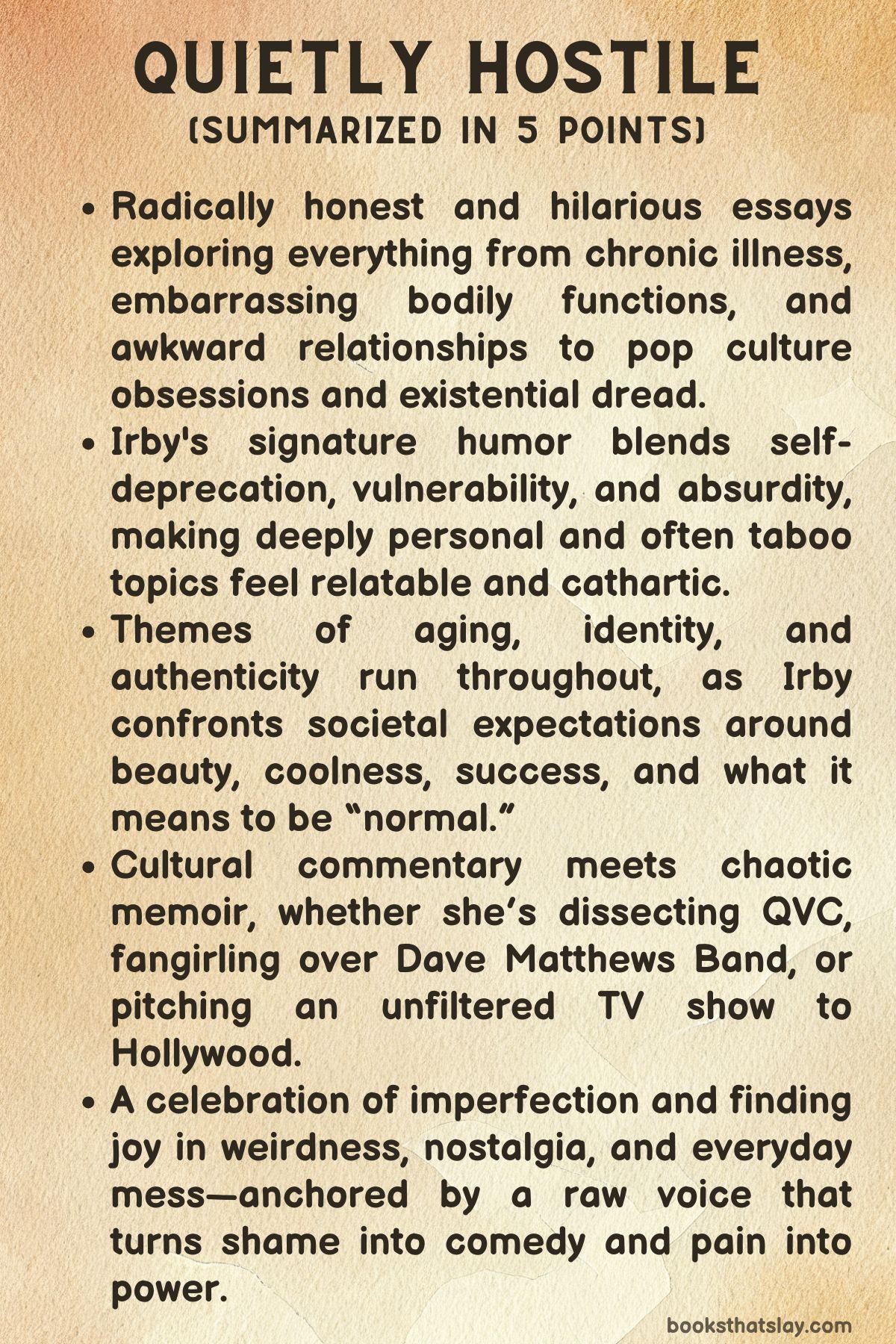

Quietly Hostile is another gut-busting, painfully honest, and emotionally sharp essay collection from Samantha Irby.

Known for her unfiltered wit and brilliant mix of comedy and vulnerability, Irby dives deep into everything from bodily disasters and pop culture obsessions to family estrangement and the humiliations of adulthood. These 17 essays read like chaotic confessions whispered by your funniest friend at a sleepover—equal parts messy, relatable, and profound. Whether she’s overanalyzing reality TV or reliving childhood memories, Irby invites us to laugh at the awkward, gross, and human moments we usually try to hide. It’s bold, brilliant, and beautifully uncomfortable.

Summary

In Quietly Hostile, Samantha Irby delivers 17 deeply personal, laugh-out-loud essays that swing from absurd to heartbreaking with masterful ease. Each chapter stands alone, yet together they form a chaotic mosaic of adult life—filtered through Irby’s unapologetically candid, self-deprecating lens.

The collection opens with “I Like It!,” a defiant ode to unashamed enjoyment. Irby challenges the cultural snobbery around taste, arguing that simply saying “I like it” is both revolutionary and freeing in a world obsessed with judgment.

It sets the tone for a book that continually rejects societal expectations, whether they concern taste, bodies, relationships, or success.

In “The Last Normal Day,” Irby rewinds to the brink of the COVID-19 pandemic. Through a hilarious, slightly manic retelling of her chaotic escape from Chicago, she captures the surreal anxiety of those early days.

Her humor shines even in crisis, balancing panic with absurdity, like when she finds comfort in gas station junk food while fleeing an impending lockdown.

Irby’s love of Dave Matthews Band is the heart of “David Matthews’s Greatest Romantic Hits,” where she breaks down the emotional highs and lows of his music with a sincerity that is both touching and funny.

In “Chub Street Diet,” she shares a brutally honest food diary, mocking the pretensions of wellness culture by highlighting her mundane, carb-heavy reality. “My Firstborn Dog” is a tender tribute to her beloved pet, full of affection and chaos, reflecting the deep bond between human and animal.

“Body Horror!” dives into the realities of living with chronic illness. Irby doesn’t spare us the awkward, gross, or painful parts.

She lays bare the disconnect between mind and body, highlighting how medical systems often treat people like a list of symptoms instead of whole humans. In “Two Old Nuns Having Amzing [sic] Lesbian Sex,” she dissects society’s discomfort with aging, queer bodies in media, and the narrow lens of desirability. It’s a provocative mix of cultural critique and wild humor.

“QVC, ILYSM” reveals Irby’s obsession with home shopping networks. She finds comfort in their soft-lit, low-stakes world, where enthusiasm for pointless products feels like a balm for real-life anxiety.

This theme of escapism continues in “Superfan!!!!!!!,” which chronicles her intense fandom for a reality show and the awkwardness of meeting a celebrity crush—an essay that exposes how starstruck adults can still act like teens.

“I Like to Get High at Night and Think About Whales” is equal parts stoner monologue and existential musing, as Irby waxes poetic about whales, death, and cosmic insignificance. In “Oh, So You Actually Don’t Wanna Make a Show About a Horny Fat Bitch with Diarrhea? Okay!” she skewers Hollywood’s resistance to raw, unglamorous stories like hers, revealing how hard it is to sell realness in an industry that prefers polish.

Essays like “What If I Died Like Elvis” and “Shit Happens” delve into bodily function and mortality with fearless, scatological glee. They’re messy, uncomfortable, and hilarious. “Food Fight” examines a petty argument with her wife, unearthing how small conflicts often mask deeper vulnerabilities in long-term relationships. “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” is a more somber, reflective piece on her estranged brother, exploring the emotional ambiguity of broken family ties.

In the final two essays, Irby turns her focus outward. “How to Look Cool in Front of Teens?” deals with her clumsy attempts to bond with her stepkids, a mix of self-consciousness and heart.

“We Used to Get Dressed up to Go to Red Lobster” ends on a nostalgic note, contrasting her humble childhood joys with her current life, reflecting on class, aging, and what we lose—or gain—over time.

Throughout Quietly Hostile, Irby embraces the uncomfortable, the gross, and the wildly human. Her essays pulse with brutal honesty, irreverent humor, and surprising emotional depth, creating a book that feels both wildly entertaining and deeply necessary.

Analysis and Themes

The Intersection of Humor and Vulnerability in Chronic Illness and Bodily Autonomy

Samantha Irby skillfully balances humor and vulnerability in addressing the complexities of living with a chronically ill body. In the essay “Body Horror!”, she delves into the absurdity and overwhelming nature of dealing with medical issues, framing her bodily struggles as both alienating and absurd.

Through candid storytelling, she reveals how a body that often feels like an enemy can also become a site of self-discovery. Irby’s use of humor to navigate discomfort and pain exposes the tension between society’s demand for sanitized portrayals of bodies and the reality of living in one that’s flawed and unpredictable.

This theme of bodily autonomy is expanded in other essays like “Chub Street Diet,” where Irby critiques the cult of highbrow food culture and embraces the messiness of everyday eating habits. She highlights how our bodies are sites of both rebellion and compliance.

Cultural Critique of Aging, Sexuality, and Representation of Queer Bodies

Irby’s exploration of aging, especially in the context of sexuality, is a recurring theme in “Two Old Nuns Having Amazing Lesbian Sex.” Through humor and critique, she contemplates how media tends to marginalize older queer women and denies them the same sexual autonomy and vibrancy granted to younger counterparts.

She critiques the discomfort society feels when confronted with aging bodies, particularly in queer contexts. Irby’s exploration is not just about reclaiming space for these bodies in narrative but also about confronting the cultural unease that arises when intimacy and sexuality are presented as part of the aging process.

This essay, much like others in the collection, tackles deeply personal issues while framing them with sharp wit and cultural analysis. It encourages readers to re-evaluate how we view both aging and queerness.

Consumer Culture, Escapism, and the Odd Comfort of Materialism

In “QVC, ILYSM,” Irby turns a seemingly trivial obsession with home shopping networks into a sharp critique of consumer culture. She acknowledges the absurdity of purchasing items one does not need while still finding comfort in the ritual of consumerism.

Through this seemingly shallow affection for QVC, Irby explores the idea of materialism as a means of emotional escape. The comfort she finds in watching people sell objects reflects a desire for simplicity and stability in a chaotic world.

Irby uses the essay to mock the culture of excessive consumption while also celebrating its role as a low-stakes, easily accessible escape from the overwhelming pressures of real life.

This theme ties into larger discussions of self-worth, consumption, and the hollow promises of consumer-driven happiness, offering a critical lens through which readers can examine their own relationships with materialism and comfort.

The Chaos and Humor of Personal Identity in a Media-Driven World

The absurdity of trying to maintain personal identity in an age dominated by media and celebrity culture is a major theme throughout Irby’s collection. Essays like “Superfan!!!!!!!” explore Irby’s fandom and starstruck behavior, offering an honest look at how we often construct personal identities based on parasocial relationships with celebrities.

Irby hilariously examines the disconnect between the images we project to the world and the awkward, real personas we harbor underneath. In “Oh, So You Actually Don’t Wanna Make a Show About a Horny Fat Bitch with Diarrhea? Okay!” she confronts the entertainment industry’s discomfort with unconventional characters, particularly those whose stories are raw, messy, and unpolished.

The essay critiques Hollywood’s reluctance to embrace bodies and experiences that don’t conform to sanitized, idealized narratives. Irby’s examination of identity in the age of media exposure questions how much of our public selves are shaped by external expectations and how much we genuinely control.

Reclaiming the Ordinary: Finding Joy in Everyday Moments and Nostalgic Reflections

A deeply personal theme emerges in “We Used to Get Dressed up to Go to Red Lobster,” where Irby reflects on childhood memories and the simple pleasures that once brought immense joy. Through the lens of a seemingly mundane family outing, she examines class, growing up, and how perceptions of value shift over time.

This nostalgia-infused piece critiques how society has moved away from cherishing small, everyday joys, instead focusing on grandiose achievements and consumer-based happiness. Irby’s reflections encourage a revaluation of those ordinary, often overlooked moments that can hold immense meaning in the context of personal history and memory.

In a similar vein, essays like “I Like It!” delve into the liberating power of unapologetically embracing personal tastes and preferences, even when they don’t align with mainstream trends. Irby’s ability to take the simplest of moments and transform them into deeply insightful reflections on identity and satisfaction makes her work a commentary on how we often overlook the richness of our own lives in pursuit of external validation.

The Humor of Coping with Mortality, Shame, and Legacy

In “What If I Died Like Elvis,” Irby humorously confronts the universal fear of death while exploring the deeply personal anxiety of leaving behind an embarrassing or insignificant legacy. By using the image of Elvis Presley’s public death as a metaphor for how we fear to die in humiliating ways, Irby turns existential dread into comedic gold.

Her reflections on mortality are laced with self-deprecating humor and the recognition that death, in its inevitability, is also absurd. This theme of confronting death and shame while weaving humor through the narrative is further explored in “Shit Happens,” where Irby recounts a humiliating, yet deeply human, experience of gastrointestinal disaster.

Both essays use the rawness of human vulnerability as a tool to cope with the darker aspects of life, reminding readers that mortality and shame are universal experiences to be navigated with both honesty and laughter.