Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton Summary and Analysis

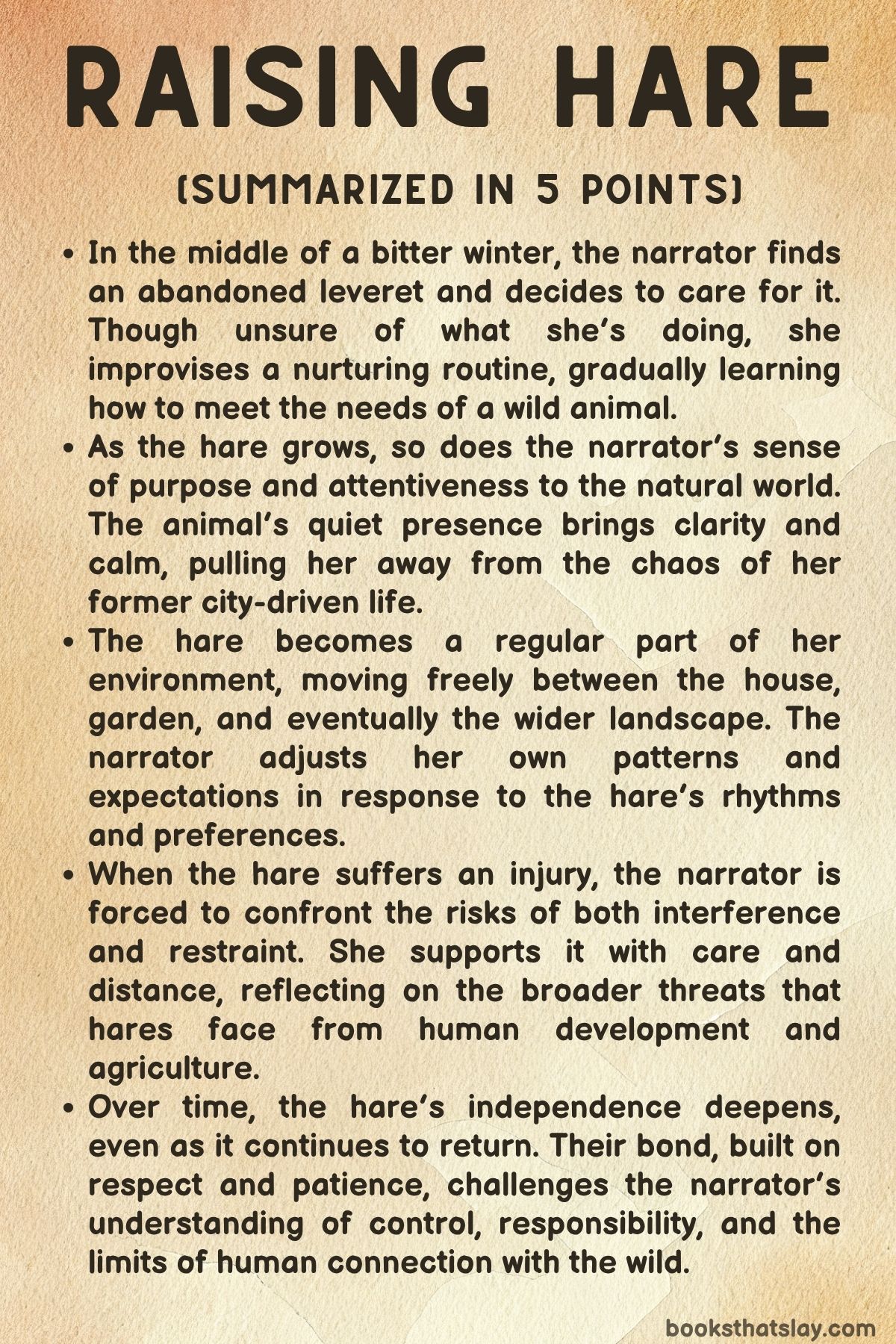

Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton is a contemplative and immersive memoir that documents the author’s unexpected relationship with a wild hare. Set against the backdrop of the British countryside, the book chronicles her experience of finding a baby leveret during a severe winter and making the life-altering decision to raise it.

What begins as a simple act of compassion unfolds into a deeply transformative journey. Through close observation and gentle care, Dalton captures the emotional complexity of interspecies relationships, the quiet rituals of nature, and the existential shift that occurs when one tunes into the rhythms of the wild. The book is both personal and ecological, rooted in quiet reverence.

Summary

Raising Hare begins during the deep winter, where snow blankets the rural English landscape and life for wildlife is tenuous. Amid the harsh weather, a pregnant hare gives birth to a leveret distinguished by a white star on its brow.

The baby is tucked away in a safe place by its mother but is soon exposed to danger when a dog approaches. Hearing the disturbance, the narrator intervenes and finds the newborn alone.

Confronted by the decision to either leave the animal to fate or intervene, she chooses to rescue it, compelled by an intuitive sense of care and protection.

The author has no prior experience raising a wild animal. Yet, from that moment forward, she commits to nurturing the tiny creature.

She improvises feeding techniques, warms it with hot water bottles, and attempts to replicate the natural environment of its species. Her fear of imprinting the animal with human behaviors is ever-present, and she avoids naming it to retain its wild essence.

Despite this, a bond begins to form—not one of domestication but of close observation and mutual presence. The leveret becomes part of her daily existence, not as a pet but as a being with its own instincts, growth, and agency.

As the leveret develops, it influences the author’s internal world. Having stepped away from a high-paced, demanding career in foreign policy due to the pandemic, she finds herself rooted in a quieter, rural life.

The presence of the hare shifts her orientation from achievement and adrenaline to stillness and attentiveness. The hare’s silent wisdom, its genetically encoded behaviors, and its instinctive relationship to the land become a source of insight.

The narrator finds herself slowing down, adapting her life to meet the hare’s needs, and in the process, unlearning the metrics of urban productivity and ambition.

As spring approaches, the leveret’s coat changes, and its strength becomes apparent. The narrator understands that its wild nature must be honored and supported.

Rather than constraining it within the house, she gradually opens up the garden, removes fences, and allows it increasing freedom. The leveret begins to navigate both domestic and natural spaces with ease, sleeping under furniture and appearing beside her during quiet moments, but always returning to the outside.

Its movement between these two worlds creates a rhythm of presence and absence that teaches the narrator how to hold on and let go at the same time.

Eventually, the leveret leaps over the garden wall, a physical and symbolic act of transition. While the author mourns the loss of proximity, she also recognizes this as the natural culmination of her role—not to keep the animal but to prepare it for autonomy.

Remarkably, the hare continues to return, appearing regularly, which leads to a deeper and more respectful relationship based on freedom and mutual recognition.

A significant shift occurs when the hare is injured—likely due to its repeated jumps over the high garden wall. The narrator is faced with a choice: intervene through veterinary care or provide quiet support without handling it.

She chooses the latter, allowing the hare space to recover naturally while ensuring food and shelter are accessible. The hare does recover, and the experience reinforces the vulnerability of wild creatures in a world shaped by human industry.

The author becomes more attuned to the dangers surrounding wildlife: agricultural machinery, roads, habitat destruction. This awareness leads her to take action, such as expanding hedgerows and restoring ponds, to create a safer environment for hares and other animals.

The story then pivots toward a remarkable development—the hare returns and gives birth to a litter in the author’s garden and, later, inside her office. The author witnesses the same precise maternal care she once tried to emulate: the hare feeds her leverets at night, hides them during the day, and fiercely protects them.

Observing this, the author is struck by the hare’s instincts and intelligence, which contradict the traditional portrayal of hares as skittish or passive. Through close observation, she sees a new level of depth and emotional capacity in the animal.

The young leverets begin to explore their surroundings, mirroring the early days of their mother. Each has a distinct personality—one bolder and eager to push boundaries, the other more reserved and cautious.

Their play, curiosity, and emerging independence offer a new layer of richness to the narrator’s life. She finds herself reorganizing her home around their needs, preserving quiet, reupholstering furniture for familiarity, and adapting her behavior to minimize stress on the animals.

What began as an impulsive act of kindness has now reshaped her entire way of being.

Eventually, one of the leverets dies unexpectedly. The loss is intimate and sharp, underscoring the fragility of life.

The author buries her beneath a rose bush and reflects on the hidden violence of modern agricultural life, where countless hares and birds are killed in mechanized harvesting. She criticizes the disregard embedded in industrial efficiency and urges for greater awareness, habitat protection, and alternative methods that prioritize coexistence.

In the final chapters, the original hare gradually becomes more distant again, as do her remaining leverets. The narrator does not feel abandoned; instead, she understands that wildness cannot be owned or held onto.

The hares continue to move through and around the property, appearing unpredictably, always maintaining their autonomy. What lingers is not a loss but a presence—a reminder of the relationship they shared.

By the end, the author’s transformation is complete. She no longer views herself as a rescuer or owner but as a participant in a shared world.

Her life has been reshaped by the quiet influence of a wild animal and its kin. The story closes not with an ending, but with an ongoing awareness of the interconnectedness between species, the dignity of wild life, and the possibility of coexisting with gentleness, respect, and humility.

Raising Hare is ultimately a chronicle of presence—of seeing, listening, and honoring life in all its unscripted forms.

Analysis of The Key People and Metaphorical Characters

The Narrator

At the heart of Raising Hare is the narrator herself, a woman whose identity is shaped as much by introspection as by the physical and emotional demands of her journey with the hare. Initially portrayed as a former foreign policy professional accustomed to high-adrenaline, structured environments, the narrator enters the story at a moment of personal and professional displacement.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupts her urban life and career trajectory, prompting a return to rural solitude. Her encounter with the abandoned leveret marks the beginning of a profound transformation.

The narrator is not simply a caregiver; she becomes a student of nature, of patience, and of relinquishment. Her early uncertainty and anxiety about how to raise a wild animal reflect a deeper existential unease, one that gradually finds grounding through the hare’s presence.

As she adapts her routines, silences her home, and becomes attuned to the hare’s needs, the narrator relinquishes control in favor of observation and reverence. Her character arc is one of deceleration and surrender: shedding the identity of mastery in favor of interdependence and humility.

Her journey with the hare also rekindles a relationship with the land and its rhythms, reinvigorating her curiosity for natural history and ecological stewardship. In the end, she is not the hare’s owner or even its rescuer, but its witness—someone who has been changed not by action, but by stillness and trust.

Through this transformation, the narrator evolves into a more grounded, open-hearted, and aware individual, committed not to control but to coexistence.

The Leveret (The Hare)

The leveret, later revealed to be a female, is the central nonhuman character in Raising Hare, yet she embodies a richness of personality and a depth of presence that challenge any simplistic divide between human and animal. From her first appearance as a fragile infant marked with a white star on her forehead, the leveret exudes both mystery and resilience.

Initially vulnerable, dependent on the narrator for food, warmth, and safety, she rapidly grows in strength and spirit. Her development mirrors the natural intelligence and wild autonomy of her species: she learns to leap, to forage, to observe, and to disappear.

Her personality is neither meek nor predictable—she is simultaneously affectionate and aloof, present yet unknowable. The leveret’s unique traits—her sensitivity to sound and scent, her territorial awareness, her silent communication—stand in contrast to the domestic expectations often placed on animals.

She chooses when to appear and when to vanish, leaping garden walls with grace and defying all containment. Despite being raised within human proximity, she retains her wildness, never succumbing to domestication.

This autonomy renders her both awe-inspiring and heartbreaking. When she returns injured or brings her own young into the house, her actions are driven by instinct and trust, not dependence.

Her presence is transformative not only for the narrator, but as a symbolic force in the narrative—a teacher, a mirror, and a conduit to the wild. Her legacy is not just her survival but her embodiment of what it means to be truly free: rooted in place, guided by instinct, and never owned.

The Leverets (The Hare’s Offspring)

The young hares born to the leveret in the narrator’s home are delicate, vivid embodiments of the next generation—both of wildness and of hope. They are unnamed and largely silent characters, but they exert a powerful emotional and thematic presence.

Their early lives are marked by secrecy and protection, fed under the cover of night, and gradually introduced to the human-tinged environment of the narrator’s house and garden. Observed with a mixture of awe and trepidation, they become emblems of nature’s quiet persistence and the fragile continuity of life.

Each leveret develops a distinct personality: one bold and curious, the other reserved and slow to part from the safety of the home. These traits echo the mother hare’s earlier journey and reinforce the idea that wildness carries many forms—bold and quiet, visible and hidden.

The sudden death of one leveret is a devastating blow, starkly reminding the narrator and the reader of the ever-present precarity that defines the lives of wild animals. Yet even in death, the leveret remains dignified, buried with ceremony and respect.

Through these young hares, the narrative explores cycles of life and the intimate, often painful, edges where human care meets the uncontrollable forces of the natural world. They are not simply extensions of their mother or symbols of innocence; they are wild lives in their own right, worthy of attention and respect.

The Landscape

While not a character in the conventional sense, the landscape of Raising Hare is so deeply entwined with the emotional and narrative arc that it functions as a silent yet powerful presence. The British countryside, with its stark winters, thawing springs, and agricultural scars, shapes both the hare’s development and the narrator’s reawakening.

The land is at once beautiful and brutal: it offers shelter, forage, and space, yet also harbors threats in the form of machines, predators, and human interference. The narrator’s growing attunement to the landscape—its hedgerows, seasonal shifts, wild herbs, and creatures—mirrors her emotional grounding and philosophical realignment.

The land becomes a living entity, one that responds to respect and suffers under neglect. It is within this ever-changing environment that all characters live and evolve, underscoring the central truth of the narrative: that no creature, human or hare, exists outside of the ecological web.

Through her careful stewardship—restoring ponds, extending hedgerows, advocating for safer harvesting methods—the narrator responds not only to the needs of the hare, but to the broader call of the land itself. In doing so, the landscape ceases to be a backdrop and becomes a character—wounded, healing, and alive.

Themes

Interdependence Between Humans and the Natural World

The account in Raising Hare centers on a profound relationship that develops between the narrator and a wild hare, establishing a deeply reflective portrayal of interdependence between human life and the rhythms of the natural world. This theme manifests not only in the initial act of rescuing the leveret, but more crucially, in the subtle and sustained transformations that follow.

The narrator, whose prior life was governed by high-stress professional commitments and urban speed, finds herself adjusting her entire routine around the hare’s comfort and survival. She reorients her sleeping schedule, quiets the household, and even restores a piece of furniture for the hare’s sense of familiarity.

These actions signal a reversal of human-centered control, as the author begins to occupy a position of humility and stewardship rather than dominion. The hare’s instincts become a kind of instruction manual for a slower, more conscious form of existence—one that urges the narrator to listen, wait, observe, and relinquish her assumptions about control.

This relationship is not about taming or dominating a wild animal, but about entering into a shared rhythm, a form of coexistence that redefines care as mutual awareness. The hare’s return visits after its departure underscore a voluntary bond grounded in trust, not ownership.

The narrator recognizes that while she may provide shelter, nourishment, and protection, the hare ultimately belongs to a separate world that overlaps with hers but is not dependent on it. The bond persists in this overlap, not in possession.

Through this lens, the book proposes a different model for how humans can relate to non-human life—not as masters or saviors, but as co-inhabitants of an increasingly threatened environment. The careful, responsive attention the narrator extends becomes a gesture of reciprocity, rather than charity.

This ecological humility reshapes not only her daily life but her entire understanding of belonging in the world.

The Complexity of Letting Go

The decision to open the garden gate and later witness the hare’s leap over the wall initiates a central emotional and philosophical inquiry into the nature of letting go. What begins as an act of rescue becomes increasingly fraught with questions about agency, control, and freedom.

The narrator confronts the reality that care, when extended beyond its necessary moment, risks turning into captivity. As the hare matures, the act of releasing it into the wild becomes not just a logistical challenge but a psychological reckoning.

She must allow the animal to follow its instincts, even if it means exposing it to harm, discomfort, or permanent departure. This tension is heightened when the hare becomes injured—possibly by her repeated leaps into and out of the enclosed space—and the narrator is forced to question whether to seek medical intervention or allow nature to proceed uninterrupted.

Rather than assert her will or default to human-centric problem-solving, the narrator chooses to remain present but passive, offering support without intrusion. This act becomes a powerful metaphor for the difficulty of relinquishing control in relationships—whether with animals, people, or even parts of the self.

Letting go is portrayed not as abandonment, but as a gesture of trust. It honors the autonomy of the other, even in the face of potential loss.

The hare’s eventual return, and later, her choice to birth her young in the narrator’s office, reflects the trust that can arise when freedom is respected. In doing so, the author reimagines what it means to love something wild: not by clinging to it, but by creating the conditions in which it might return of its own volition.

This theme resonates far beyond the specific narrative, offering insights into parenting, friendship, and healing from personal attachments that must be allowed to change or dissolve.

Grief and Fragility in the Non-Human World

The sudden and silent death of one of the leverets punctuates the narrative with a moment of intimate grief that underlines the broader fragility of wild lives. Despite doing everything possible to provide safety and comfort, the narrator is confronted with the limits of care and the unpredictability of life.

The leveret’s body remains beautiful even in death, a striking image that complicates the common impulse to associate beauty with vitality. The narrator buries the leveret beneath a rose bush, not as an act of sentimentality but as an acknowledgment of its individuality and the quiet mark it left on her life.

This moment becomes a portal into a wider reckoning with the systemic threats that face wildlife: mechanized farming, habitat fragmentation, and the absence of ecological mindfulness in modern human activity.

The brutal harvest of a nearby potato field provides a stark contrast to the delicate coexistence cultivated at home. Adult hares, leverets, and even a bird of prey are killed by machines, collateral damage in the pursuit of agricultural efficiency.

The author’s grief shifts from the specific to the systemic, as she begins to see how ordinary human practices perpetuate vast and invisible suffering. Her advocacy for wildlife-friendly farming practices emerges from this grief—not as a call to sentiment but as an ethical imperative.

In this light, the death of the leveret is not merely a personal loss but a microcosm of a larger ecological crisis. The fragility of wild creatures is laid bare, not in their weakness, but in the vulnerabilities imposed upon them by human systems.

This theme transforms the personal mourning into a call for awareness and change, urging readers to consider the consequences of our collective indifference and the urgent need for more compassionate land stewardship.

Transformation Through Stillness and Observation

The narrator’s inner metamorphosis is anchored in her growing ability to be still—to watch, to listen, and to learn without agenda. As her life shifts away from the demands of professional ambition and the metrics of productivity, she finds a different mode of meaning rooted in attentiveness.

The hare’s presence teaches her to regard slowness not as passivity but as attentiveness, and observation not as detachment but as deep engagement. From noticing the leveret’s silent chitters to tracking her offspring’s foraging patterns, the narrator begins to experience time differently.

She trades deadlines for seasons, noise for quiet, and goals for presence. This transformation is not dramatic or sudden; it accumulates through consistent, quiet acts of noticing.

Her curiosity leads her into fields like botany, natural history, and herbal medicine—not for mastery but for communion.

This new way of being is marked by a willingness to relinquish the ego-driven urgency of modern life and embrace the unstructured rhythms of the wild. The author’s attention is no longer directed by obligation but by wonder.

She learns to inhabit the same liminal space the hares occupy—part inside, part outside; part known, part unknowable. This liminality is where transformation occurs.

As the hares grow bolder and wilder, the narrator herself becomes more grounded and expansive. Her sense of identity detaches from achievement and reorients around care, perception, and reciprocity.

This theme suggests that transformation does not always arise from action or willpower but from surrendering to the quiet intelligence of the natural world. In being stilled by the hare, the narrator recovers a way of living that feels more authentic and sustaining, offering a powerful counterpoint to the prevailing culture of speed and control.

Trust and Interspecies Communication

Trust between species is portrayed not as a mystical or sentimental connection but as a slow, cautious, and deeply meaningful form of mutual recognition. In Raising Hare, the narrator earns the hare’s trust not through dominance or domestication but through sustained respect for her instincts.

The hare decides to return, to raise her young near the narrator, and to expose her most vulnerable moments—feeding, nesting, recovering—to human presence. These actions are not interpreted as signs of dependence but as signals of confidence in the boundaries the narrator has maintained.

In turn, the narrator learns to recognize subtle cues in the hare’s behavior—movement patterns, posture shifts, territorial preferences—as a kind of language that demands attention and care.

This communication is not verbal but sensorial. The narrator modifies her household in ways that accommodate the hare’s needs, from silencing visitors to restoring furniture that anchors the hare’s memory.

These gestures are responses in a silent conversation that affirms the possibility of peaceful cohabitation across species. The narrator does not impose meaning on the hare’s choices but allows them to be what they are: unpredictable, partial, and profoundly real.

Trust here is not about control but about relinquishing control in favor of presence. It is built slowly, through consistency and attention, and it is rewarded not with ownership but with a fleeting, precious connection that must always be respected.

This theme elevates the idea of interspecies relationship from novelty to necessity, presenting it as a model for how humans might live more ethically and attentively within the broader web of life.