Realm of Ice and Sky Summary, Analysis and Themes

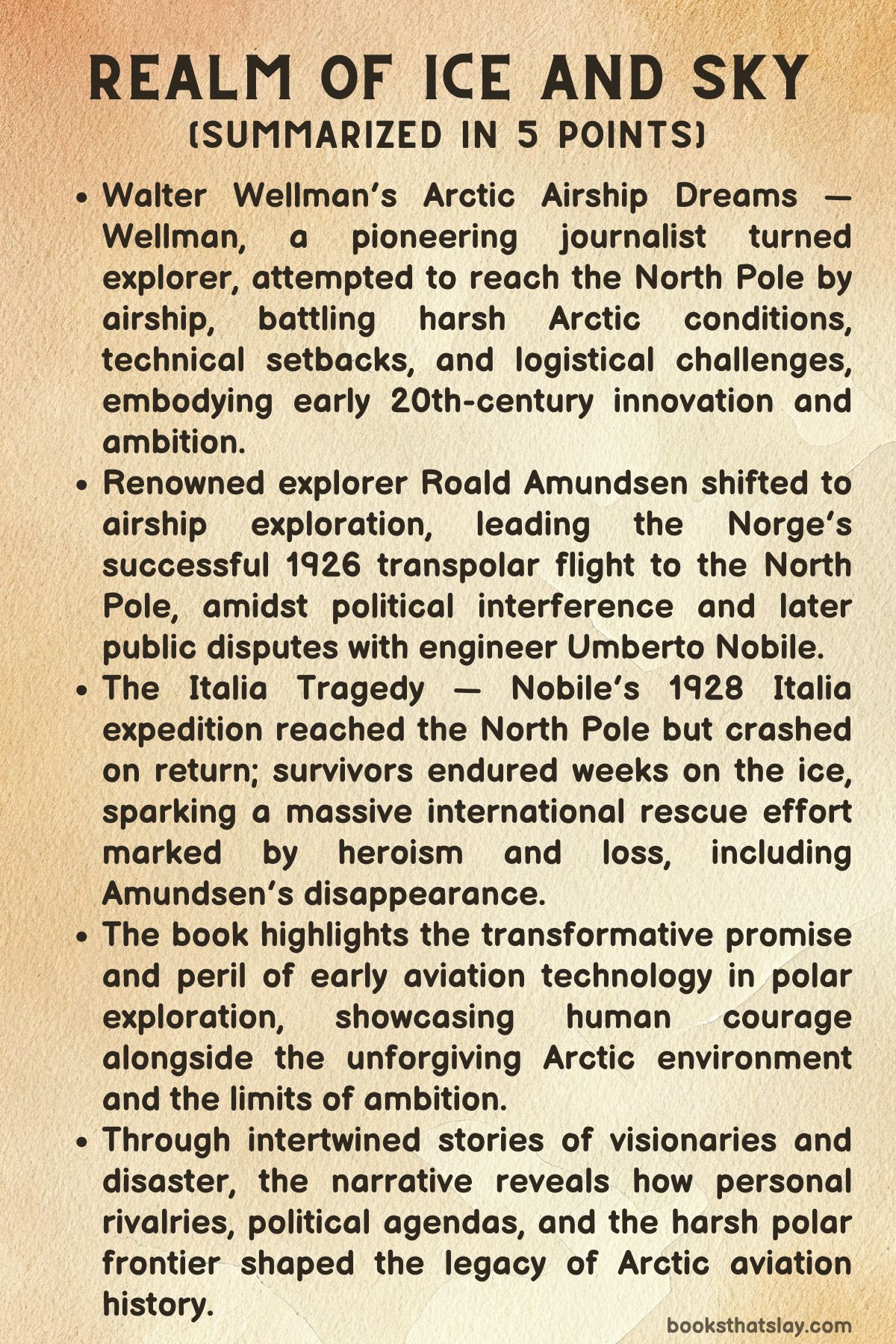

Realm of Ice and Sky by Buddy Levy is a historical narrative that captures the daring spirit of early 20th-century exploration and aviation. It chronicles the dramatic quests to reach the North Pole and cross the Atlantic by airship, focusing primarily on the American explorer Walter Wellman and Italian general Umberto Nobile.

With meticulous research and cinematic pacing, Levy reconstructs the blend of technological ambition, national rivalry, and human endurance that defined these expeditions. From the icy barrens of the Arctic to the tense airspace over the Atlantic, this book illustrates the triumphs, failures, and legacies of those who dared to bring humanity to the skies of the world’s most unforgiving frontiers.

Summary

Realm of Ice and Sky begins by tracing the intertwined histories of polar exploration and the invention of human flight. For centuries, the North Pole had resisted all terrestrial attempts at conquest.

By the early 1900s, as aviation began to mature, visionaries saw the sky as the solution to this geographical enigma. Airships—hydrogen-filled dirigibles powered by engines—emerged as potential vehicles for Arctic travel.

Among those driven by this dream was Walter Wellman, a journalist and explorer who had already failed multiple times to reach the Pole by traditional means. His experiences had left him physically battered but mentally sharpened in his belief that aerial navigation offered a new way forward.

Wellman’s prior Arctic attempts in the 1890s were plagued by shipwrecks, frostbite, and even death. These failures convinced him that conventional sled-and-ship routes were doomed.

Rebounding from public and personal defeat, he decided to embrace modern engineering. With financial support from the Chicago Record-Herald and the endorsement of prominent figures like Alexander Graham Bell and President Theodore Roosevelt, Wellman pursued his plan to construct a specialized airship.

He collaborated with French engineers to build America, a massive dirigible outfitted with a gasoline engine, a gondola reinforced with steel, and a novel drag device called an equilibrator to regulate flight altitude.

In 1907, Wellman’s team built Camp Wellman on Danes Island in the Arctic as a base of operations. After enduring technical challenges, hostile weather, and mechanical unreliability, the America finally launched in September.

Almost immediately, it ran into trouble: dense fog, navigation failures due to magnetic anomalies, and erratic wind currents. After several perilous hours in the sky, the crew was forced to crash-land on a glacier.

Although the airship survived largely intact and all men and animals were safe, the mission was a public disappointment. Still, Wellman portrayed the voyage as a vital learning opportunity, promising a return.

The team regrouped and returned in 1909 with a rebuilt America. The updated version featured twin engines and refined control systems.

This time, however, their hangar was destroyed by Arctic storms, and a key team member, Knut Johnsen, was killed. Undeterred, Wellman launched again in August.

Shortly after takeoff, the equilibrator broke away, causing the airship to ascend wildly. Battling high winds and failing engines, the crew crash-landed again—this time near a ship that towed them back to safety.

The America’s gas envelope detached and exploded in the sky, marking the symbolic end of Wellman’s dream. Shortly thereafter, Frederick Cook and Robert Peary each claimed to have reached the Pole, ending any hope of Wellman becoming the first.

He pivoted to a new challenge: crossing the Atlantic.

By 1910, Wellman launched another version of the America, now outfitted for oceanic travel with upgraded engines and a pioneering wireless system. The airship lifted off from Atlantic City with six crew members and was cheered by spectators.

The journey encountered fog, mechanical failure, and harsh weather. After traveling nearly 1,000 miles over the Atlantic, the team was forced to abandon the mission and were rescued by a passing ship.

While he never reached his goal, Wellman’s efforts significantly advanced the public understanding of airship potential and the limits of early aviation.

The narrative shifts to the Italia expedition of 1928, led by Italian general and engineer Umberto Nobile. Building on previous Arctic aviation milestones, Nobile took command of a new dirigible, the Italia, for a mission to the North Pole.

Initially successful, the return journey met catastrophe when the airship crashed in a violent storm. The control car was ripped from the ship, stranding Nobile and nine others on the ice while the rest of the airship drifted away with six men aboard.

Despite a broken leg and diminishing authority, Nobile took charge, organizing a survival camp and salvaging materials. The Red Tent, a crimson-colored shelter, became the central hub of their survival efforts.

With limited supplies and a damaged radio, the stranded men tried to maintain morale. One of the crew, Biagi, managed to transmit intermittent SOS messages.

Meanwhile, physicist Malmgren, plagued by guilt and injury, attempted suicide but was saved by his companions. Eventually, Malmgren, along with Zappi and Mariano, set out on foot to seek help.

Their journey was marked by suffering and sacrifice. Malmgren died from exposure, while Mariano developed frostbite and snow-blindness.

Zappi refused to leave his side, and the two were eventually rescued by a Soviet aircraft from the Krassin icebreaker, though Mariano’s injuries required immediate amputation.

Back at the Red Tent, morale lifted when Biagi confirmed that a Soviet farmer had picked up their SOS. An unprecedented international rescue followed, involving 16 ships and 23 aircraft from eight countries.

Despite political tensions, the shared goal of saving the survivors united nations. Eventually, all remaining men were rescued by the Krassin, which also recovered the symbolic Madonna of Loreto and scientific instruments.

In the aftermath, Nobile was airlifted from the ice by Swedish pilot Einar Lundborg, but the Italian government stripped him of authority and branded him a coward for leaving his men. Meanwhile, Lundborg’s own plane crashed on a subsequent rescue flight, leaving him stranded for days.

The survivors, though initially celebrated, were swept into political controversy. Roald Amundsen, the famed Norwegian explorer and Nobile’s one-time rival, vanished while participating in the rescue, further complicating public perception.

Years later, Nobile was vindicated. He published his own memoir and regained honor after the fall of Mussolini.

His pioneering contributions to polar aviation were finally acknowledged. The book closes by reflecting on the broader legacy of Wellman, Nobile, and Amundsen, whose efforts shaped the future of aviation and transformed the dream of conquering the skies into a reality forged in ice, steel, and human resolve.

Characters

Walter Wellman

Walter Wellman is the fiery nucleus of Realm of Ice and Sky, embodying the convergence of ambition, ingenuity, and relentless resilience in the face of overwhelming adversity. A journalist by profession and an explorer by compulsion, Wellman emerges as a complex figure driven as much by national pride and public spectacle as by scientific curiosity and personal obsession.

His repeated, failed expeditions to the North Pole did little to dampen his determination—instead, they honed his belief that human triumph in the Arctic demanded a technological revolution. The airship America, thus, was not merely a vehicle of transportation for Wellman, but an audacious manifestation of modernity, a floating laboratory, and a theatrical stage from which to announce the conquest of the unknown.

Wellman’s story is marked by physical peril and psychological endurance: shipwrecks, crevasse falls, wild animal attacks, and grueling Arctic winters failed to extinguish his quest. Yet what distinguishes him is not just his endurance but his visionary foresight.

He grasped the symbolic power of wireless communication and aerial mobility long before they became mainstream, and his insistence on broadcasting success in real time from the top of the world reflects both a deep belief in journalism’s evolving role and a yearning for immortality through media. Even after multiple airship failures, he persisted—not out of delusion, but out of an almost spiritual commitment to progress.

Ultimately, Wellman’s inability to reach the Pole or cross the Atlantic does not tarnish his legacy; rather, it enshrines him as a pivotal transitional figure whose daring paved the way for later, more successful pioneers.

Umberto Nobile

General Umberto Nobile is a poignant counterpoint to Wellman—an innovator, leader, and tragic hero whose legacy is both elevated and haunted by the events of the 1928 Italia disaster. As a dirigible engineer and pilot, Nobile is at the pinnacle of technical skill and visionary leadership, yet his most defining traits surface not in victory, but in collapse.

When the Italia crashes onto the ice, severing its gondola from the floating envelope, Nobile’s command transforms from one of aviation to one of emotional and existential survival. Despite a broken leg and fractured morale, he becomes the emotional anchor of the Red Tent survivors, orchestrating their routines, maintaining discipline, and rallying hope in the most abject conditions.

Nobile’s decision to leave the Red Tent for strategic coordination—a move made under orders—turns into a devastating personal ordeal. Vilified by the Fascist government and Italian media as a coward who abandoned his men, he suffers public disgrace and professional exile.

Yet the narrative offers a nuanced, almost redemptive arc. It shows a man whose integrity, foresight, and humility outlive political condemnation.

His efforts to maintain order during the crisis, his emotional intelligence in dealing with trauma-stricken crewmen, and his eventual vindication decades later all portray a man of depth, conviction, and human fallibility. Nobile’s arc, ending in quiet restoration, reflects the high human cost of leadership and the lasting value of moral endurance.

Melvin Vaniman

Melvin Vaniman is the mechanical heart of Wellman’s dream—a figure who channels raw ingenuity into fragile, hopeful machinery. As the chief engineer of the airship America, Vaniman is not merely a technician but a co-visionary, designing structural innovations that include the strengthened gondola, advanced rudder mechanisms, and the groundbreaking equilibrator.

His role is instrumental, not decorative. Without Vaniman’s mechanical creativity and resourcefulness, Wellman’s dream would have remained a concept on paper.

Yet Vaniman is not just a man behind the machines. He faces the same risks, endures the same brutal conditions, and eventually joins Wellman in the ill-fated transatlantic attempt, demonstrating courage equal to his competence.

What sets Vaniman apart is his quiet reliability and adaptive mindset. When disasters strike—whether through storm damage, engine failures, or crash landings—he works tirelessly to salvage what remains and prepare for the next attempt.

Unlike Wellman, who carries the public face of the mission, Vaniman is the unsung hero who embodies the technical audacity required for Arctic exploration by air. His tragic death during the transatlantic expedition underscores the thin margin between vision and catastrophe.

Yet in death, as in life, Vaniman represents the crucial alliance between science and adventure, a partnership without which the era of dirigible exploration would never have taken flight.

Finn Malmgren

Finn Malmgren is a character etched in psychological depth and emotional fragility. A meteorologist on Nobile’s Italia expedition, Malmgren is devastated when his weather predictions prove fatally flawed, leading in part to the crash.

His descent into self-reproach and mental anguish adds a tragic dimension to the Red Tent narrative. While others focus on survival, Malmgren turns inward, battling guilt, shame, and ultimately suicidal despair.

This internal conflict becomes central to his character arc, making him not merely a victim of circumstance but a reflection of the unbearable psychological toll that failure can exact in high-stakes environments.

His attempted suicide and subsequent decision to join Zappi and Mariano on a foot journey to seek help further illuminate his complexity. He chooses to risk everything in pursuit of redemption.

When physical injury eventually overcomes him, he is left behind by his companions—an abandonment that is less a betrayal than a tragic inevitability. Malmgren’s presumed death in the Arctic tundra resonates deeply within the broader themes of the book: the limits of endurance, the solitude of guilt, and the haunting possibility that some wounds cannot be mended even by survival.

Filippo Zappi and Mariano

Zappi and Mariano are both embodiments of loyalty and determination, yet they also represent contrasting dimensions of endurance and human connection. Zappi is the stalwart officer, resilient and unwavering, who takes on the near-suicidal trek across the ice with a clear sense of duty.

His commitment to both survival and companionship becomes evident in his refusal to abandon Mariano despite the latter’s debilitating injuries. Zappi’s journey is one of grit and stoicism, but also of empathy—his insistence on staying with Mariano is a deeply human gesture in a landscape that rewards cold pragmatism.

Mariano, on the other hand, suffers some of the expedition’s worst physical consequences, including snow blindness, gangrene, and the eventual loss of his foot. His body breaks down, but his resolve does not.

The dynamic between the two men—one able-bodied and determined, the other physically wrecked yet mentally tenacious—adds emotional gravity to the survival tale. Their rescue by the Krassin airship, after excruciating delays, becomes a small miracle not just of navigation but of compassion and endurance.

Together, they underscore the profound bonds forged in extremity and the resilience of friendship under duress.

Giuseppe Biagi

Giuseppe Biagi, the wireless operator of the Italia, is the expedition’s unseen savior. Working under catastrophic conditions, with a damaged radio and limited power, Biagi sustains the crucial thread of communication that ultimately ensures the survival of the Red Tent occupants.

His perseverance in the face of endless failure, his ability to repair and maintain the lifeline device, and his emotional support of his fellow survivors position him as a pillar of the group’s survival. Biagi is not a leader in the traditional sense, but his technical prowess and unwavering steadiness make him essential.

His ability to break through the silence of the Arctic wasteland—reaching a Soviet farmer who would trigger an international rescue—cements his legacy not as a hero of action, but as one of precision and patience.

Roald Amundsen

Roald Amundsen appears more as a mythic presence than a central participant in Realm of Ice and Sky, yet his role is symbolically profound. Already a global icon as the first man to reach both poles, Amundsen enters the narrative during the Italia rescue mission, responding to the SOS calls despite his rivalry with Nobile.

His disappearance during the rescue becomes a haunting and poetic conclusion to a life defined by conquest and courage. Amundsen represents the older, romanticized age of exploration—one that operated on prestige, endurance, and national glory.

His final act, undertaken for a rival he once belittled, reveals an underlying nobility and binds him forever to the legacy of polar aviation. His presumed death during the rescue adds gravitas to the narrative and anchors the saga in both triumph and tragedy, cementing his status as a tragic hero of the skies.

Themes

Human Ambition and the Pursuit of Glory

The narrative of Realm of Ice and Sky is propelled by the unrelenting human ambition to achieve what had long seemed impossible: conquering the Arctic skies. Walter Wellman emerges as the embodiment of this pursuit, channeling a near-obsessive desire to be the first to reach the North Pole by air.

His determination is not limited to geographic triumph; it is entangled with the broader aspirations of modernity—scientific achievement, national pride, and personal redemption. His repeated attempts, despite catastrophic failures and public ridicule, highlight a particular strain of human ambition that refuses to be subdued by nature or circumstance.

The Arctic becomes not only a physical destination but a crucible in which man’s desire to transcend his limitations is tested. Wellman’s inclusion of wireless communication as part of the mission suggests that conquest alone wasn’t sufficient—it had to be broadcast, shared, and mythologized.

This need to leave an indelible mark, to be remembered as a pioneer, reflects a profound belief that human history is shaped by those who defy reason and endure hardship in pursuit of greatness. The theme also extends to General Umberto Nobile and Roald Amundsen, whose motivations were equally steeped in the symbolism of heroism and legacy.

In both triumph and failure, the quest for glory looms large, demonstrating how ambition often eclipses practicality and safety, but also drives innovation and historical milestones.

Innovation Versus Nature

Throughout Realm of Ice and Sky, the tension between technological innovation and the mercilessness of the natural world is constant and unyielding. Airships—products of cutting-edge engineering and human ingenuity—are repeatedly pitted against the Arctic’s unpredictable winds, magnetic anomalies, and vast icy landscapes.

The airship America, despite being outfitted with reinforced gondolas, experimental equilibrators, and wireless communication, proves inadequate against the forces of nature. This contrast exposes the limits of human control and foresight, reminding readers that even the most advanced machinery can be rendered helpless by weather, topography, and ice.

Wellman’s technical enhancements in the 1907 and 1909 attempts are detailed and impressive, yet they consistently fall short in practice. Likewise, Nobile’s Italia, though expertly designed and captained, cannot withstand the compounding impact of fog, ice, and mechanical stress.

These encounters with the Arctic serve as humbling reminders that innovation must grapple with a natural world that is neither passive nor predictable. The narrative does not dismiss the value of progress but tempers it with caution, portraying technology as aspirational but inherently vulnerable.

Rather than triumph over nature, these missions become dialogues with it—costly, risky, and, at times, fatal. The clash between invention and environment reinforces a central reality: progress is never guaranteed to win, and success in exploration requires not only ingenuity but humility before the natural order.

Nationalism and the Theater of Exploration

The expeditions chronicled in Realm of Ice and Sky are inseparable from the nationalistic fervor of their respective eras. Exploration is repeatedly framed as a performance of national strength, innovation, and superiority.

Wellman’s missions are not merely personal endeavors; they are underwritten by powerful backers like the Chicago Record-Herald, and symbolically endorsed by figures such as President Theodore Roosevelt. These affiliations elevate the act of exploration to a form of geopolitical messaging.

By attempting to plant a national presence at the top of the world, Wellman and his contemporaries were staking symbolic claims on behalf of their countries, competing for visibility on the world stage. The use of wireless communication to announce a victory from the Pole, in real time, exemplifies how these expeditions were designed as spectacles for public consumption and national validation.

The later Italia expedition unfolds under the shadow of Fascist Italy’s propaganda apparatus, which seizes control of the narrative and casts Nobile’s decisions in a politically charged light. His evacuation is recast as cowardice, and his authority revoked not because of failure, but because it no longer served the regime’s mythos.

Exploration thus becomes theater, shaped as much by state agendas and public opinion as by actual events. The heroes of these missions are made or unmade by political convenience, reminding readers that national pride can distort truth and compromise ethical leadership in the name of spectacle.

Survival and Psychological Endurance

The theme of survival is not limited to physical endurance but encompasses the deep psychological toll exacted by Arctic exploration. In Realm of Ice and Sky, moments of extreme isolation, trauma, and loss challenge the mental fortitude of every character involved.

Paul Bjørvig’s winter spent alone with a corpse exemplifies the existential horror that often accompanied polar missions. His ordeal is not marked solely by cold and hunger but by solitude and the burden of memory.

Similarly, the Red Tent survivors of the Italia disaster exhibit a profound resilience rooted not just in resource management, but in emotional discipline, communal cohesion, and faith. The meticulous routines they maintain—cooking, storytelling, spiritual rituals—are not trivial distractions but essential psychological lifelines.

General Nobile’s leadership, despite his physical injury, hinges on his ability to provide emotional stability and structure in the face of despair. Even the act of shooting a polar bear becomes symbolically important, extending not only their physical sustenance but also their collective sense of agency.

The expeditioners’ suffering reveals a harsh truth: the Arctic does not merely test bodies; it fractures and reforms minds. The trauma suffered by men like Malmgren, who attempts suicide after his weather miscalculations, underscores the unbearable burden of perceived failure in extreme contexts.

Ultimately, the theme of survival extends beyond escaping death—it is about maintaining identity, dignity, and hope in a world that offers no mercy.

Redemption, Reputation, and Historical Memory

The question of how explorers are remembered—whether as visionaries or failures—permeates the entire narrative of Realm of Ice and Sky. Walter Wellman’s efforts, though unsuccessful in their original aims, are ultimately framed as stepping-stones in aviation history.

His vision of using wireless communication, his belief in dirigible travel, and his endurance in the face of repeated defeat all contribute to a legacy that, while mocked in his time, is later acknowledged as pioneering. The same ambiguity surrounds Umberto Nobile, who is vilified by the Fascist regime not because of his decisions in the field, but because those choices contradict the image of infallible leadership Mussolini wished to project.

Nobile’s eventual vindication decades later, following the fall of the regime, underscores how reputations are constructed, destroyed, and sometimes rebuilt based on shifting political and cultural contexts. These fluctuating legacies show that the history of exploration is not merely written in action but in interpretation.

It also highlights the danger of allowing public perception and state ideology to dictate historical truth. The narrative ultimately argues for a more nuanced understanding of heroism—one that accounts for sacrifice, intention, and complexity rather than simple success or failure.

Redemption is presented not as a narrative reward but as a long-term process of historical re-evaluation. The explorers’ reputations evolve over time, shaped by memoirs, scholarship, and the eventual recognition of their contributions to the broader arc of human achievement.