Red Clay Summary, Characters and Themes | Charles B. Fancher

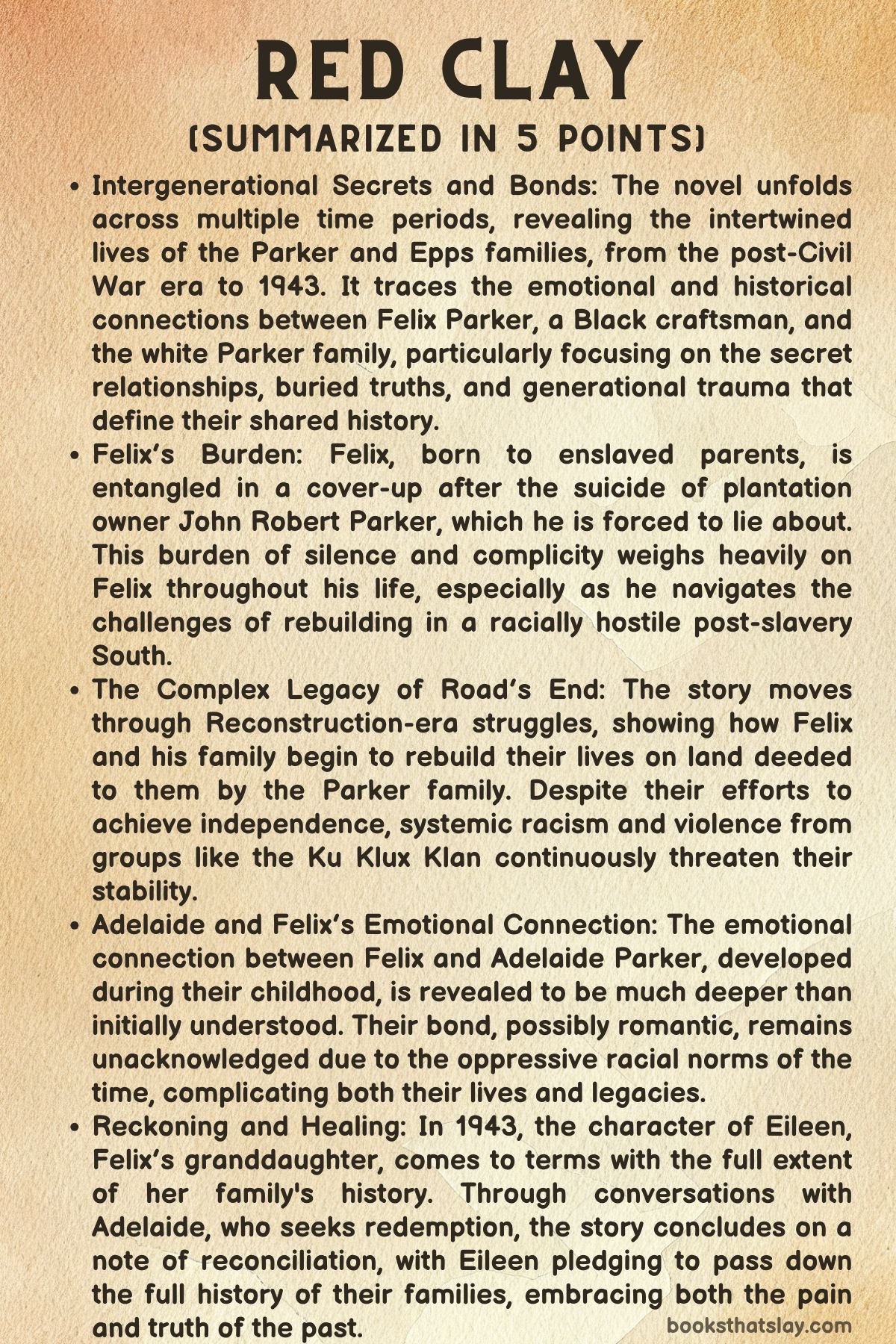

Red Clay by Charles B. Fancher is a compelling narrative that explores themes of family, legacy, and historical ties in the context of the American South.

Set in the small town of Red Clay, Alabama, the story revolves around the life of Felix H. Parker and his family, spanning multiple generations. The novel delves into the emotional and social complexities faced by its characters, from the trauma of enslavement to the search for identity in the post-Reconstruction era. It intricately examines the intertwining of personal and historical struggles, highlighting the resilience and strength of the Black community amid the harsh realities of racism and oppression.

Summary

In 1943, the funeral of Felix H. Parker takes place at Third Baptist Church in Red Clay, Alabama, marking the end of an era.

Felix, a well-respected man in the community, has passed away, and his granddaughter, Eileen Epps, is at the center of the grief-stricken family. As she sits in the front pew, she reflects on her grandfather’s life, recalling his wisdom, pride in their Black heritage, and the way he instilled a sense of community and strength within their family.

Eileen remembers how Felix, who had been a former slave, always emphasized the importance of quality craftsmanship and honest labor. His passing represents the end of a generation that had endured and resisted the oppressive forces of society.

Eileen’s recollections are interrupted by her memories of the peculiar woman, Eula Jean Wilkins, who would fall into trances during church services. Felix had always urged her to observe these moments, finding joy in the woman’s spiritual connection, which contrasts with the sorrow of his death.

As the funeral continues, Eileen notices an elderly white woman in attendance, someone she does not recognize. After the service, the woman mysteriously disappears, leaving Eileen unsettled.

The next day, the mystery surrounding the woman deepens when she arrives at Eileen’s home in a 1940 Packard 180. The woman introduces herself as Miss Adelaide Parker, claiming a past connection to Felix and his family.

She insists that there are important secrets about Felix’s life that need to be uncovered. Initially unsure of the woman’s intentions, Eileen invites her in.

Their conversation reveals a hidden aspect of Felix’s past, one that was never shared with his family. Miss Adelaide’s revelation marks the beginning of a journey for Eileen, one that will uncover truths about her grandfather’s life that are tied to a history of racial and familial complexity.

The narrative shifts back to Felix’s childhood as a young enslaved boy. He witnesses the violent death of his master, John Robert, which sets off a series of events that shape his future.

His evolving relationship with Addie, the master’s daughter, forms the emotional core of his early years. Addie, though initially sympathetic, becomes determined to uncover the truth about her father’s death, sensing that Felix is hiding something.

As Felix grapples with the weight of this secrecy, he is forced to confront his own fears and the growing power dynamics between him and Addie. Meanwhile, Addie’s mother, Marie Louise, struggles to adjust to life after her husband’s death, taking control of the plantation and making decisions that will impact both the family’s future and their relationship with the enslaved people.

Felix is eventually moved to the fields, where he works alongside other enslaved laborers, exposed to the brutal realities of plantation life. The shift in his status from house servant to field laborer represents a symbolic loss of innocence, as he navigates the dangerous relationships with fellow workers, including Big Joe, a bully who exploits his position of power.

Felix’s desire to fight back against Big Joe is a form of resistance, one of the few means of agency available to him in a world that limits his options.

As the narrative unfolds, it delves deeper into the psychological and emotional toll of enslavement and the post-emancipation struggles faced by Felix and his family. Felix’s parents, Elmira and Plessant, continue to work through the challenges of economic dependence, despite being free.

The idea of land ownership becomes central to their hopes for the future, though the reality of racial and economic barriers proves to be a constant struggle. Elmira’s grief over the death of Felix’s childhood friend, Danny, serves as a reminder of the violence and systemic racism that continues to plague their lives, even in the aftermath of slavery.

The death of Danny further emphasizes the fragility of freedom in a society where Black people remain second-class citizens, subject to the whims of white supremacy.

Felix’s journey takes a new turn when he is given an opportunity to take over a carpenter’s shop, a trade he had learned under the mentorship of John, an aging carpenter. Felix’s work ethic and ambition shine through as he strives to build a future for himself and his family.

However, the death of his friend Danny continues to haunt him, as it serves as a stark reminder that the freedoms he seeks are not easily attained. Despite this, Felix’s determination to succeed and break free from the constraints of his past remains strong, even as he faces personal and familial turmoil.

The story also explores the broader social and political changes in the South during the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction periods. Felix’s story intersects with the shifting dynamics of race, class, and power as the plantation economy crumbles and the nation faces the challenges of rebuilding in the aftermath of the Civil War.

The economic, social, and racial tensions that permeate the landscape of the South are woven into the fabric of Felix’s personal story, adding depth to the narrative and highlighting the complex legacy of slavery and freedom.

In 1881, the story transitions to Paris, where Addie returns after two years of separation from her former lover, Étienne Dupuis. Their reunion brings both comfort and discomfort, as Addie discovers that Étienne has moved on with his life, married, and has a daughter.

Despite this, Addie’s visit reignites the emotional connection between them, and she contemplates her fleeting presence in his life. The brief affair marks another chapter in Addie’s journey of self-discovery, as she navigates the complexities of love, loss, and identity.

Upon her return to Red Clay, Addie learns of her brother Claude’s death and inherits a ten-acre plot of land at Road’s End. This inheritance sparks a series of events that force Addie to confront unresolved family issues and the legacy of her family’s land.

She decides to donate the land to the American Missionary Association, establishing a school for Black children in honor of her late father. This decision represents a symbolic act of progress and education, serving as a testament to the changing times and the need for Black empowerment in a society that has long marginalized them.

As the narrative comes to a close, Addie reflects on the impact of her actions, finding peace in the knowledge that the land will serve as a beacon of hope for future generations. However, the emotional and familial conflicts that persist in her life remind her that legacy is not just about inheritance, but about the choices one makes to shape the future.

Through Felix’s story and Addie’s journey, Red Clay presents a powerful exploration of identity, family, and the lingering effects of history.

Characters

Felix H. Parker

Felix H. Parker is a central figure whose life is defined by both the weight of history and his personal resilience.

As a young man living in post-Reconstruction Alabama, Felix navigates the complexities of his identity and his responsibilities within a community marked by racial tension. His character is shaped by his early experiences as an enslaved boy, witnessing the violent death of his master, John Robert, which marks a pivotal moment in his life.

Felix’s internal struggles are compounded by the power dynamics at play, particularly his complex relationship with Addie, the daughter of the plantation owner. Despite the oppressive forces in his life, Felix demonstrates quiet defiance through his reluctance to expose the truth behind John Robert’s death, a form of resistance against the institution that once enslaved him.

This inner turmoil underscores his growth from a house servant to a field laborer, and later, a skilled carpenter. Felix’s journey is one of survival, where he is confronted not only with the harsh realities of plantation life but also with his desire to escape the lingering effects of his past.

His evolving relationship with his family, particularly his mother Elmira, reflects a deep bond founded on love and mutual protection. Yet, as Felix matures, he begins to grapple with the looming threat of systemic oppression and its impact on his future, seen through the tragic death of his childhood friend Danny.

Ultimately, Felix is a figure of resilience, constantly seeking a better life while dealing with the burdens of history and identity.

Eileen Epps

Eileen Epps, Felix’s granddaughter, is a reflective and deeply empathetic character whose understanding of her family’s legacy and community is central to the narrative. In the opening chapter, Eileen’s memories of her grandfather Felix serve as the emotional anchor of the story.

Through her eyes, the reader gains insight into Felix’s wisdom, his pride in the Black community, and the resilience that defined his life. Eileen’s character is marked by a blend of reverence for her grandfather’s strength and a quiet curiosity about the mysteries of his past.

As she navigates the complexities of grief, particularly after Felix’s death, Eileen begins to confront the uncomfortable truths about her family’s history. The arrival of Miss Adelaide Parker, a mysterious white woman with a hidden connection to Felix, forces Eileen to reckon with long-buried secrets that challenge her understanding of her grandfather’s life.

Throughout the story, Eileen grows from a young woman mourning her loss into someone capable of facing uncomfortable truths and reinterpreting her family’s legacy. Her evolution is indicative of the broader themes of memory, family, and the complex interplay of race and history in the South.

Addie Parker

Addie Parker is a character defined by both her privilege and her internal conflict. As a member of a prominent white family in Alabama, Addie’s status is one of power and control, yet she is not immune to the emotional and moral dilemmas that arise from her family’s actions and their implications on others, particularly Felix.

Her role in the narrative is shaped by her complicated relationship with Felix, which evolves from a position of authority, where she holds power over him as a young enslaved boy, to one where she seeks reconciliation and understanding as an adult. Addie’s internal struggle is compounded by the loss of her father, John Robert, and her subsequent role in the management of her family’s estate, Road’s End.

Throughout her journey, Addie is forced to confront the realities of her privilege and the consequences of her family’s actions, particularly her involvement in the lives of those they once enslaved. Her reunion with Étienne Dupuis in Paris symbolizes her attempt to recapture lost moments of happiness, yet her realization that their connection can never be the same speaks to her broader struggles with the past and its lingering influence on her present.

Addie’s return to Red Clay to deal with the inheritance of the family’s land further underscores her desire to make amends, particularly by using the land to benefit the Black community through the establishment of a school. Her actions ultimately reflect her journey toward a more complex understanding of legacy, responsibility, and the need for healing.

Marie Louise

Marie Louise, Addie’s mother, is a matriarch navigating the shifting power dynamics in the wake of her husband’s death. As the new head of the family, she is thrust into a position where her decisions will shape the future of the plantation and her children’s futures.

Marie Louise’s character is defined by her pragmatic approach to the emotional and financial challenges she faces. Her leadership is marked by strategic decisions, such as planning the sale of the plantation and securing Claude’s role in its management, which reflect her desire to maintain stability amidst upheaval.

Despite the necessity of these actions, Marie Louise also begins to grapple with the complexity of her relationships with the enslaved individuals on the estate, including Plessant, a lifelong servant to the family. Marie Louise’s navigation of this changing world speaks to the broader theme of power and its role in shaping both personal and collective histories.

Her character is an embodiment of the tension between maintaining the status quo and confronting the injustices of the past.

Elmira

Elmira, Felix’s mother, is a strong and nurturing figure whose love and concern for her son are central to her character. Her protective instincts are evident in her attempts to shield Felix from the harsh realities of the world, such as the death of his childhood friend Danny.

Elmira’s role as a mother reflects the emotional resilience required to survive in a world that continues to impose limitations on her family’s opportunities. Despite the emancipation of her people, Elmira’s family remains shackled by economic dependence, which is most clearly illustrated by their reliance on Claude, their former master.

Elmira’s hopes for a better future for Felix are tempered by the realities of systemic racism and the ongoing struggle for survival in a world where freedom is not synonymous with equality. Her character embodies the emotional weight of a mother’s love, her desire to protect her children from the world’s cruelties, and the strength required to endure a lifetime of hardship.

Plessant

Plessant, Elmira’s husband, plays a quieter, yet significant role in the narrative, serving as a stabilizing force within the family. While his role as a father and husband is important, it is his pragmatic approach to survival and the future that defines his character.

Plessant, like Elmira, faces the challenges of post-emancipation life, struggling with the realities of land ownership and the complex dynamics of dealing with former masters. His vision for financial independence is overshadowed by the obstacles they face, particularly their dependence on Claude’s control over the land.

Plessant’s character reflects the resilience and adaptability necessary to navigate a world where the promises of freedom are frequently undermined by systemic forces.

Miss Adelaide Parker

Miss Adelaide Parker, an elderly white woman, serves as a catalyst for the revelation of Felix’s hidden past. Her arrival at Felix’s funeral and her subsequent conversation with Eileen serve to uncover family secrets that have been buried for years.

Miss Adelaide’s connection to Felix’s history as a former enslaver’s daughter brings to light the complexities of race and history in the South. Despite the power dynamics at play, Miss Adelaide’s desire to understand and perhaps make amends for the past adds a layer of moral ambiguity to her character.

Her motivations, though unclear at first, lead to a deeper understanding of the tangled relationship between the white and Black families in Red Clay, and the role of memory and reconciliation in shaping their futures.

Themes

Legacy and Family Secrets

The narrative weaves a profound exploration of legacy and the untold stories that shape the past, and ultimately, the future. At the heart of the story is Felix H.

Parker, a man whose life is defined not just by his accomplishments, but by the complex history of his family and the secrets he carries with him. When Felix passes away, his granddaughter, Eileen Epps, begins to uncover the layers of his past, revealing hidden truths that have been buried for decades.

The introduction of Miss Adelaide Parker, a white woman who claims a connection to Felix’s past, acts as a catalyst for these revelations. Through their conversations, Eileen learns of the deeply entangled histories between the Parker and Parker families, a legacy rooted in both love and oppression.

Felix’s role in the community, as well as his work as a craftsman, is a testament to the strength and resilience of Black individuals in a world that constantly seeks to marginalize them. Yet, the family’s story is far more complicated than Eileen initially understands.

The book addresses how history, especially the personal and painful parts, shapes the identities of the living, and how the revelation of these secrets forces individuals to reckon with the past in ways they may not be ready for. Eileen, in particular, must navigate the tension between honoring her grandfather’s memory and accepting the uncomfortable truths that emerge about his life.

Freedom and Oppression

The theme of freedom, particularly in the context of post-emancipation America, runs deeply through the lives of Felix and his family. Despite the legal end of slavery, the characters are far from free.

The narrative highlights the struggle of transitioning from the shackles of physical enslavement to the invisible chains of systemic oppression. Felix’s efforts to build a life as a skilled carpenter demonstrate his desire to carve out an independent existence.

However, his family’s continued dependence on their former master, Claude, underscores the economic realities that limit their freedom. Felix’s internal conflict, especially when confronted with the violent death of his childhood friend Danny, illustrates the precarious nature of Black life in a racially segregated South.

While the official end of slavery marks a legal victory, the characters are still trapped within an environment where freedom is often a fleeting, illusory concept. The tragic death of Danny serves as a stark reminder that despite physical freedom, the systemic forces of racism and poverty continue to restrict the choices available to Black individuals.

Felix’s hope for a better future is constantly tempered by the harsh realities of survival in an unjust world.

Power Dynamics and Social Hierarchies

The exploration of power dynamics and social hierarchies is central to the story, particularly in the interactions between the enslaved people and their masters. Addie, the daughter of the plantation owner, represents the privilege of the ruling class, using her position of power to demand answers from Felix, the enslaved boy.

Her status allows her to question Felix about his role in her father’s death, but Felix’s defiance is a silent protest against the structures that seek to control him. Felix’s resistance to Addie’s demands is not just a personal rebellion but also a reflection of the broader tension between the oppressed and their oppressors.

The shifting roles within the family and the plantation further complicate these power dynamics. Marie Louise, the new matriarch, assumes control over the plantation after her husband’s death, making decisions that ensure the survival of the family, but she is also forced to contend with the shifting power structures in the post-slavery South.

Her efforts to maintain financial security and manage the plantation’s future reveal the fragility of power and the ways in which wealth, race, and status continue to dictate the lives of individuals.

Identity and Self-Determination

Felix’s journey to self-determination is a central focus of the narrative, illustrating the complexities of identity formation in a world that constantly seeks to define individuals based on race, class, and past experiences. Despite the systemic barriers that limit his freedom, Felix strives to create a life for himself that transcends the labels imposed upon him.

His work as a carpenter symbolizes his desire to build something of lasting value with his own hands, independent of the constraints of slavery or the expectations of his past. However, his sense of identity is constantly shaped by his interactions with others, particularly his family.

His relationship with his mother, Elmira, is filled with both pride and fear—she wants him to succeed but also harbors deep anxieties about the dangers that await him in a society that still views Black men as threats. As the narrative progresses, Felix’s struggle to define himself becomes increasingly urgent, especially as he faces the challenges of post-emancipation life.

His internal battle reflects the broader struggle of Black individuals in a society that denies them full recognition and humanity. Ultimately, Felix’s journey becomes a fight for self-determination, one that is fraught with obstacles but also filled with hope and resilience.

Memory and the Past

Memory, both personal and collective, plays a critical role in shaping the characters’ perceptions of themselves and their relationships with others. Felix’s memories of his childhood as an enslaved boy are a heavy burden that he carries throughout his life, often clouding his ability to move forward.

His relationship with Addie, and later with his family, is haunted by the unresolved trauma of his past, a past that he cannot fully escape or share. The narrative also delves into the ways in which family history is passed down through generations.

Eileen’s reflection on her grandfather’s life is colored by the stories and memories he shared with her, but as she uncovers more about his past, she is forced to confront the discrepancies between what she believed to be true and what actually was. The theme of memory is also explored through the ways in which people selectively remember or choose to forget painful truths.

Eileen’s encounter with Miss Adelaide, and the subsequent revelations about Felix’s past, shows how the past is not something that can be neatly packaged and left behind—it continues to shape the present, forcing individuals to reckon with the legacies of their ancestors.

Loss and Grief

The themes of loss and grief are explored through the death of Felix and the emotional reverberations it causes among his family. Eileen’s reflections on her grandfather’s life, as well as her grief at his passing, are marked by a sense of unfinished business, as her grandfather’s secrets begin to surface.

The sense of loss is further compounded by the arrival of Miss Adelaide Parker, who brings with her the weight of a hidden history. The grief that Felix’s family experiences is not only a response to his death but also to the realization that his life was marked by painful secrets, some of which they may never fully understand.

Additionally, the theme of loss extends beyond death to encompass the loss of identity and agency. Felix’s family’s struggle to maintain their sense of self in a world that constantly seeks to diminish their worth is a form of ongoing grief, a mourning for the lives they could have lived if not for the systemic forces that have shaped their existence.