Rental House by Weike Wang Summary, Characters and Themes

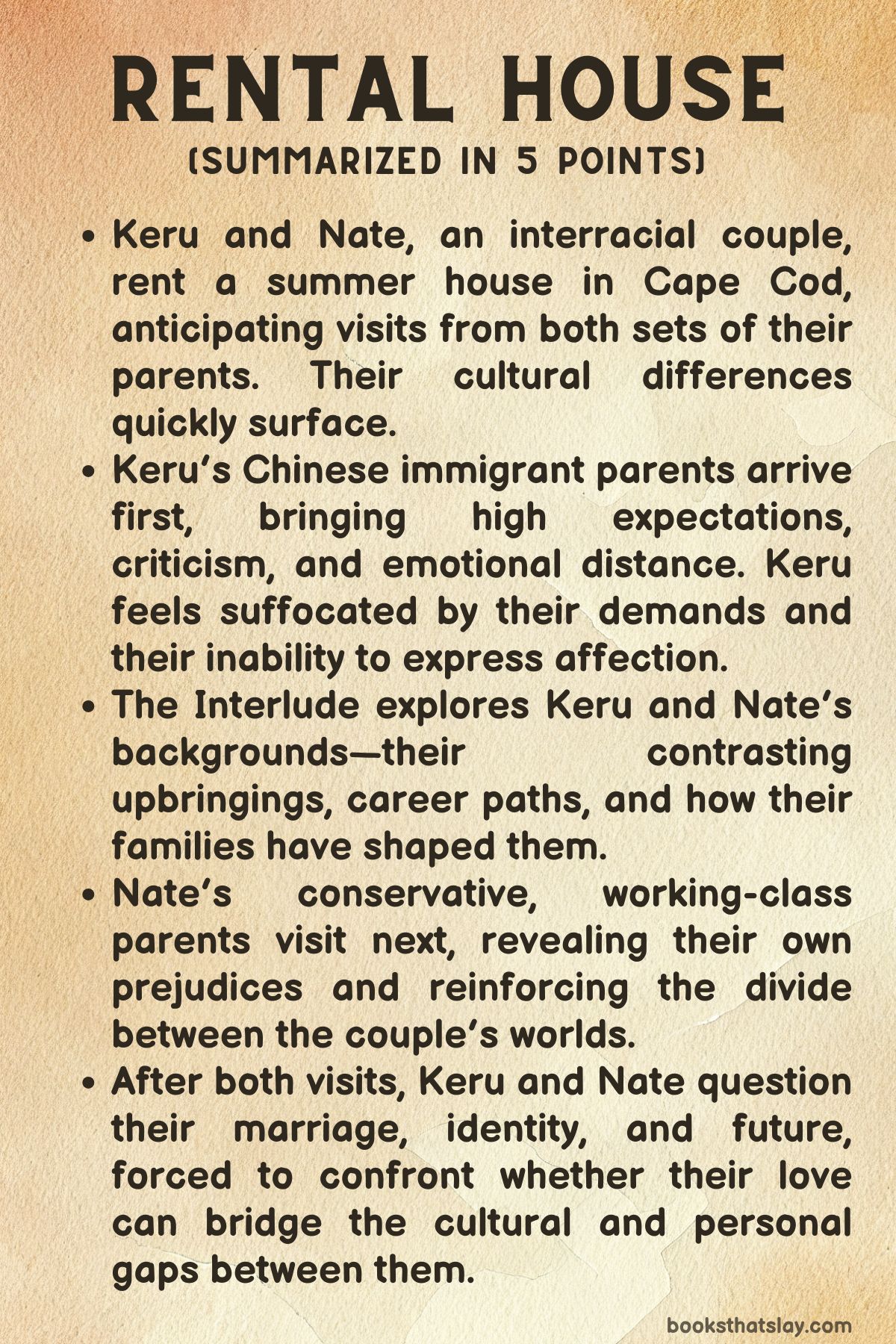

Rental House by Weike Wang is a sharp, understated exploration of marriage, identity, and the emotional labor of existing between cultures. Following Keru, a Chinese American woman, and her white husband Nate, the novel unfolds during a summer vacation that becomes a crucible for unspoken tensions.

Set across quiet domestic scenes in Cape Cod and later the Catskills, the novel eschews dramatic plots for intimate psychological insight. Wang’s prose captures the silent negotiations, buried resentments, and subtle contradictions of a modern relationship. What results is a layered meditation on cultural legacy, the invisible weight of expectation, and the fragile threads that bind people together through shared histories and compromises.

Summary

Rental House begins with Keru and Nate temporarily escaping Manhattan for a rental cottage in Cape Cod. They intend to unwind for a month while hosting their respective parents in staggered visits.

The setup is modest, yet its implications are deeply revealing. Keru, a Chinese-American professional, is immediately burdened by her parents’ visit.

Her mother and father arrive with expectations sharpened by an immigrant mindset—obsession with cleanliness, survival, and preparedness. They are hyper-vigilant, still reacting to the lingering fear of the pandemic, and their behavior dominates the space.

Keru’s father, an outspoken chemist, is particularly relentless, monologuing about fuel cells and discipline, speaking in English while Nate listens patiently but without true connection.

Keru’s mother, fearful of dogs, disapproves of Mantou, the couple’s dog. Despite her aversion, Mantou eventually becomes a neutral ground, a shared focus that provides fleeting moments of harmony.

Yet even these interactions are tinged with discomfort. Keru’s parents’ worldview, rooted in sacrifice and scarcity, amplifies her awareness of the compromises and dissonances in her marriage.

Every comment, from how she spends money to whether she plans to have children, becomes a reminder of the expectations she struggles to meet and the emotional debt she owes to her parents.

Nate’s parents arrive later, offering a different but equally complicated energy. His mother is casual, friendly, and riddled with passive-aggression.

She wants to be liked, but in her efforts she often reveals ignorance—once making a casually racist comment about Native Americans, which Nate swiftly cuts short. Though less domineering than Keru’s parents, Nate’s mother introduces a subtler discomfort.

Her attempts to relate feel hollow, and Keru feels even more like an outsider. Her mixed-race identity is rarely discussed directly, but always felt—in glances, comments, and silences.

Keru and Nate’s own dynamic is one of quiet attrition. Their communication relies on sarcasm, habit, and unspoken understanding.

The stress of hosting both sets of parents lays bare their deep cultural and emotional differences. Keru, shaped by ambition and responsibility, is contemplative about motherhood, not just because of fear of the labor involved but because of what it might mean to raise a child caught between two worlds.

Nate, more easygoing, is sympathetic but noncommittal. Their conversations reveal mismatches in values, often softened by humor but never truly resolved.

A shift occurs when the narrative jumps to the Catskills, where Keru and Nate try again for a peaceful getaway. They encounter new neighbors, Mircea and Elena, a European couple with a cultivated, bohemian lifestyle.

They speak multiple languages, raise an elegant child, and seem to embody everything Keru and Nate are not—composed, worldly, and effortlessly affluent. Keru is both intrigued and irritated by Elena, whose behavior and comments mirror a form of liberal racism.

Elena’s generalizations about Asians and interracial couples provoke Keru, who lashes out but then apologizes—an emotional contradiction that captures her internal conflict between asserting her identity and being the agreeable guest.

Nate, meanwhile, becomes increasingly withdrawn. His career feels stagnant; as a tenured biology professor, he finds little satisfaction in his work.

Keru’s professional success and financial support seem to deepen his sense of inadequacy. Their childlessness—a mutual decision—becomes more than a lifestyle choice.

It marks them as different, not only to their families but to society at large. When Elena labels them a “DINK” couple (double income, no kids), it reflects the way others reduce and categorize their existence.

The arrival of Nate’s brother, Ethan, and his girlfriend, Morgan, marks another disruption. Ethan is opportunistic and entitled, seeking money from Nate under the guise of launching a gym business.

His resentment toward Nate’s success, and Keru’s skepticism of his intentions, ignite buried familial tensions. Nate, who has always managed his family through avoidance, can no longer suppress his discontent.

Ethan’s intrusion forces him to reflect on the emotional distance he’s created and the effort it takes to maintain the facade of civility.

Keru’s interactions with Morgan also expose her vulnerabilities. Hoping to bond, she joins Morgan on a run, only to injure herself.

The act is less about exercise and more about proving she belongs, about being seen and accepted. But Morgan remains indifferent, revealing that not every attempt to connect will be reciprocated.

Keru’s repeated efforts to smooth over discomfort—whether with Elena, Morgan, or Nate’s mother—show how deeply she’s internalized the need to adapt, even when it hurts.

As the story approaches its conclusion, Keru and Nate reach a quiet reckoning. Their frustrations manifest symbolically when Keru throws a flaming log into the house—not as an act of destruction, but a moment of emotional combustion.

It encapsulates years of microaggressions, silence, and compromise. It’s irrational, but deeply honest.

The final scenes take place five years later. Their lives have shifted in practical ways—ageing parents, evolving careers—but emotionally, things remain tenuous.

Keru is now the financial backbone of both families, a role that leaves her tired but in control. Nate continues to wrestle with his masculinity and purpose.

Their marriage endures, not through passion or reinvention, but through routine, shared responsibilities, and a mutual, if muted, care. Time has hardened certain boundaries—visits are shorter, conversations more contained—but it has also clarified what matters.

In a moment of symbolic clarity, Keru insists on dignity and respect within a family triangle involving Nate and Ethan. Her command is not dramatic but definitive.

She is no longer interested in appeasement. Her assertion is less a victory than a survival strategy—a choice to define her own terms.

Rental House offers no dramatic catharsis. Its brilliance lies in its accumulation of subtle tensions, quiet compromises, and the slow erosion and reinforcement of bonds.

Through Keru and Nate, the novel questions whether love alone is enough to bridge cultural divides, and whether identity can ever be safely unburdened from history. The ending suggests that while perfection is out of reach, something resembling stability—if not happiness—can be forged through self-awareness and the daily choice to stay.

Characters

Keru

Keru stands at the emotional and thematic center of Rental House, embodying the intersection of cultural duality, familial responsibility, and personal longing. As a Chinese-American woman raised by immigrant parents, she internalizes their ethos of discipline, vigilance, and ambition.

Her life, shaped by scarcity and sacrifice, is marked by an acute sensitivity to rules, expectations, and judgments—both spoken and implied. This manifests in her hyperawareness of social norms and microaggressions, particularly when interacting with her white in-laws, her neighbors, and even strangers.

Her attempts to navigate these spaces reflect a lifetime of trying to assimilate while never truly being allowed to forget her difference.

Her identity is layered with contradictions. Despite her success as a high-achieving professional and provider, Keru carries deep-seated insecurities about belonging.

Her past relationships reveal a pattern of racialized rejection, reinforcing her sense of otherness. Even in her marriage to Nate, a man she clearly loves, she remains tethered to a legacy of immigrant trauma and generational expectations.

Her sense of duty toward her aging parents, her cultural caution, and her reluctance about motherhood all illustrate a character caught between competing imperatives: to honor the past while carving a future that is her own. In scenes of confrontation—whether with Nate’s family, strangers at the beach, or Elena’s prejudices—Keru often reacts with controlled anger or repressed emotion, underscoring the exhausting performance of navigating white spaces as a person of color.

Her quiet breakdowns and surreal moments, such as throwing a flaming log, speak to the simmering rage beneath her composed exterior. She is a portrait of resilience and fragility, constantly calculating what must be endured and what can be resisted.

Nate

Nate represents a subtler but equally conflicted subject within Rental House—a man from a working-class Southern background who has intellectually and geographically distanced himself from his origins, yet remains emotionally ensnared. As a tenured academic disillusioned with the hollow routines of university life, Nate is fatigued by bureaucratic obligations and disengaged students, and increasingly adrift from a sense of purpose.

His upbringing, shaped by religious guilt and masculine expectations, continues to influence how he performs in the roles of husband, son, and brother. Though generally gentle and deferential, Nate often retreats into passivity, relying on politeness to navigate tension and sidestepping difficult emotional reckonings.

His marriage to Keru is defined by affection, fatigue, and misunderstanding. He sympathizes with her anxieties, particularly around identity and family, but often fails to fully engage with them.

His discomfort with confrontation, especially with his own mother’s casual racism or his brother Ethan’s manipulations, reveals a man who wants peace at any cost—even when that cost is Keru’s emotional labor. Nate’s insecurities surface most acutely in the presence of the European neighbors and in the economic disparity between him and Keru.

His loss of traditional masculine identity, especially in the later years when he becomes financially dependent, adds a layer of quiet crisis to his character. Yet his enduring connection to Keru, through their shared weariness and understated solidarity, shows his capacity for tenderness and growth, even if imperfectly realized.

Keru’s Parents

Keru’s parents are emblematic of the immigrant generation whose worldview is forged by scarcity, danger, and the relentless pursuit of stability. They bring to the Cape Cod rental their entire system of beliefs: obsessive cleanliness, paranoia, and vigilance.

Their behavior—scrubbing surfaces, washing the dog’s paws, scrutinizing every detail of the cottage—is more than eccentricity; it is survival logic transplanted into a new world that remains uncertain and potentially hostile. Keru’s father, a chemist passionate about fuel cells, dominates conversations with his intense monologues, revealing not only his intellectual rigor but also his emotional rigidity.

He exemplifies the immigrant father archetype—brilliant, demanding, emotionally distant, and often incapable of recognizing the emotional needs of others, particularly his daughter.

Keru’s mother, though quieter, enforces discipline through silence and judgment. Her fear of dogs and her eventual acceptance of Mantou is a minor but telling arc: even small gestures of change come slowly and with great internal resistance.

These parents, in their own flawed way, represent love—a love expressed through critique, anxiety, and sacrifice rather than affection or praise. Their presence forces Keru to relive her childhood tensions and to reckon with the lingering influence of their approval and disapproval.

The trauma they passed down, wrapped in the language of care, continues to shape Keru’s identity, even in middle age.

Nate’s Parents

Nate’s parents present a contrasting American family model—less rigid, more expressive, but no less problematic. His mother, in particular, is a complex figure: cheerful and eager to connect, but prone to passive-aggressive remarks and unexamined racial and cultural assumptions.

Her desire to be liked, especially by Keru, comes across as performative, with gestures of inclusivity undermined by deeply ingrained biases. Her defense of Keru at the beach is a surprising, almost redemptive act, but the subsequent resumption of cultural insensitivity shows that her progress is limited.

Nate’s father is more peripheral, largely characterized by a laid-back attitude and detachment, reinforcing the contrast with Keru’s intense and involved parents.

Nate’s family functions on a kind of emotional shorthand rooted in politeness, avoidance, and surface-level affection. Their warmth lacks the gravitas of Keru’s familial responsibility, but it is not without weight.

Nate’s internal conflict—his loyalty to his roots and his discomfort with them—is illuminated through these interactions. The racial ignorance and class assumptions of his parents challenge his self-conception as an enlightened academic, and by extension, his ability to be the kind of partner Keru needs.

Mircea and Elena

Mircea and Elena, the cosmopolitan European neighbors in the Catskills, operate as both a foil and a mirror for Keru and Nate. Fluent in multiple languages, raising a well-mannered child, and exuding cultured ease, they represent a seemingly effortless sophistication that unsettles the American couple.

Their lifestyle—refined, mobile, worldly—triggers both admiration and resentment. For Keru, Elena’s casual cruelty and ignorance, especially in discussing mixed-race identity and Asian culture, feel like an affront masked by politeness.

Her own need to maintain social harmony leads her to apologize for her justified outrage, revealing the deep, internalized expectation to placate and smooth over discomfort.

Mircea’s passive-aggressive interest in Nate and his subtle critiques expose the vulnerability Nate feels in his masculinity and accomplishments. The European couple becomes an ideological test: their liberal veneer contrasts sharply with the underlying cultural arrogance they exhibit.

They highlight the fallacy of progressiveness that lacks self-awareness—a recurring theme in Keru and Nate’s encounters with the world outside their marriage. While the neighbors serve as instigators, their role is less about their own depth and more about what they reveal in others: Keru’s suppressed rage and Nate’s identity crisis.

Ethan and Morgan

Ethan, Nate’s estranged brother, is the embodiment of the American familial burden: entitled, self-righteous, and trapped in a narrative of resentment and underachievement. His reappearance with Morgan, his girlfriend, brings unresolved childhood dynamics to the surface.

Ethan’s proposal of a gym venture is less about entrepreneurship and more about manipulation—a means to extract resources from a brother whose life he envies but cannot comprehend. His presence forces Nate to confront the version of himself he left behind, and to reckon with the guilt and superiority that such abandonment engenders.

Morgan, by contrast, is young, indifferent, and largely uninterested in familial harmony. Keru’s attempt to bond with her—culminating in a physical injury during a run—illustrates Keru’s emotional exhaustion and desperate need for connection.

The indifference Morgan offers in return is a cruel but clarifying mirror: not all bridges can be built, and not all efforts will be met halfway. Ethan and Morgan thus catalyze a turning point in the couple’s understanding of boundaries—what can be mended, and what must be refused.

Mantou

Though a minor figure, Mantou—the dog—serves as a potent symbol of tension, assimilation, and evolving intimacy in Rental House. Initially a source of conflict, especially for Keru’s mother who is afraid of dogs, Mantou slowly becomes a point of shared affection and compromise.

Dubbed the “panda dog,” he shifts from outsider to a beloved presence, revealing how emotional attachments can transcend initial fears. His behaviors—his refusal to pee in the rain, his selective affections—reflect the household’s undercurrents of resistance, obedience, and emotional negotiation.

Mantou becomes a creature through which love, favoritism, and tolerance are explored, offering silent but poignant commentary on the central theme of coexistence.

Themes

Cultural Dissonance and Ethnic Alienation

In Rental House, cultural dissonance is not simply a background condition—it animates nearly every interaction, shaping Keru’s consciousness and decision-making. As a Chinese-American woman embedded within a marriage to a white man, Keru straddles two cultural frameworks that often conflict in tone, values, and expectations.

Her parents’ worldview, forged by immigration, scarcity, and a lifelong rehearsal of caution, contrasts starkly with the performative casualness and cultural ignorance of Nate’s white Southern family. From her father’s monologues on scientific rigor to her mother’s obsession with hygiene, Keru is made to feel accountable for translating and mediating cultural codes.

She is often hyper-aware of her body, tone, and presence, constantly trying to avoid offense or misinterpretation. That tension becomes acute when encountering subtle racism, whether through microaggressions from Nate’s mother or patronizing comments from acquaintances like Elena.

Keru endures these moments with internalized diplomacy—responding with polite silence or apologetic restraint, even when insulted. The emotional labor of navigating this space weighs heavily, and the frustration builds in moments such as the surreal act of throwing a flaming log—a desperate eruption from years of constrained affect.

The cultural dissonance doesn’t resolve; rather, it accumulates into an ambient exhaustion. In Keru’s marriage, her workplace, and her attempts at friendship, her identity is often misread or flattened.

The gap between how others perceive her and how she understands herself creates a subtle but persistent alienation, one that underscores the conditional nature of belonging in multicultural settings shaped by American whiteness.

Marital Negotiation and Emotional Labor

Keru and Nate’s marriage operates less like a sanctuary and more like a battleground for competing emotional legacies, unresolved expectations, and silent compromise. The relationship is built on love, but it survives on negotiation.

Their conversations, punctuated by sarcasm and moments of quiet disconnection, suggest a couple intimately familiar with each other’s rhythms but also burdened by accumulated grievances. Nate’s tendency to retreat into passive listening, whether with Keru’s father or in response to his own family’s dysfunction, frustrates Keru, who bears more of the emotional weight.

She is the primary financial provider, the cultural interpreter, the anticipator of consequences. His silence, while sometimes sympathetic, often functions as avoidance.

Meanwhile, Keru wrestles with fears of motherhood, intergenerational trauma, and the possibility of repeating cycles of judgment and conditional love. Nate’s noncommittal responses are not antagonistic, but they offer little reassurance.

The marriage is neither explosive nor dispassionate—it occupies a tense middle ground marked by care worn thin by the constancy of responsibility. Their mutual affection is expressed through routine, pet care, in-jokes, and shared weariness rather than grand romantic gestures.

The friction of their differences—cultural, familial, emotional—never fully resolves. Yet there is resilience in the ordinariness of their bond.

They find moments of solidarity in fatigue, in laughter, and in recognizing the absurdity of their surroundings. The story presents marriage not as a site of redemption or collapse, but as an ever-evolving exchange—marked by effort, empathy, and the unglamorous work of coexisting.

Generational Expectations and Familial Obligation

The generational divide in Rental House runs deeper than differences in age or worldview—it reflects diverging moral economies shaped by survival, guilt, pride, and silence. Keru is tethered to the expectations of her immigrant parents, whose sacrifices and paranoia have etched themselves into her psyche.

Their obsession with cleanliness, money, and respectability is not just behavioral—it is existential, born from decades of discipline, suffering, and deferred dreams. These values permeate their interactions with Keru, who is both their pride and their project.

She is expected to maintain their standards, to succeed without complaint, and to bear their emotional weight without defiance. Nate’s parents, while less overtly demanding, exert their own kind of pressure—through passive aggression, micro-racism, and emotional evasiveness.

Nate is cast in the role of the accommodating son, expected to absorb dysfunction without resistance. Both Keru and Nate are caught in cycles of inherited obligation, struggling to break free while fearing disapproval or rejection.

The visits from each set of parents are not just social calls—they are rehearsals of intergenerational trauma. Keru’s memories of judgment, Nate’s resentment toward his brother, and the subtle but cumulative weight of family dynamics all surface during the summer and Catskills episodes.

The story shows how adult children, even when independent, remain emotionally entangled in the legacies of their upbringing. This burden shapes how they love, how they fight, and how they imagine their futures.

Familial obligation becomes not just a logistical concern, but a moral and psychological force that dictates much of their internal landscapes.

Identity, Belonging, and the Fragility of Acceptance

Keru’s identity is not a fixed narrative but a constantly shifting performance influenced by her surroundings, her company, and her memories. Her longing to belong—to be understood without translation, to be liked without effort—is rendered with aching precision.

As a woman of color in predominantly white spaces, her sense of self is repeatedly subjected to tests of tolerance. The incident with Elena, and earlier missteps from Nate’s mother, crystallize how acceptance often comes with caveats.

Even when defended or included, Keru cannot trust the consistency of that embrace. Her reflex to apologize, to explain, to soften her anger, reflects a lifetime of managing other people’s comfort.

She feels neither fully at home with her in-laws nor entirely free with her own family, where obligation can obscure affection. Her attempts to connect with Morgan—pushing herself physically to gain rapport—mirror the broader emotional contortions she performs daily.

Nate, too, performs versions of himself depending on his audience: the loyal son, the supportive husband, the rational liberal. Yet these masks grow heavier as each character questions their authenticity.

The story suggests that belonging, when conditional, is itself a source of alienation. Even marriage, often seen as a promise of home and acceptance, becomes another arena where Keru’s identity must be negotiated.

Ultimately, her most grounded moments are not in validation from others but in assertions of self—her refusal to excuse ignorance, her demand for respect, her quiet acknowledgment of what she endures. The fragility of acceptance, especially across racial and cultural lines, is laid bare through her experience.

Class Tensions and the Illusion of the American Dream

Class operates as both an explicit and implicit tension throughout Rental House, revealing how deeply it shapes relationships, self-perception, and aspiration. Nate’s working-class Southern roots and Keru’s immigrant upbringing represent two distinct yet overlapping experiences of striving.

For both, success is not inherited but earned—through education, relocation, and painful distancing from their origins. Yet the illusion of arrival—that achievement secures ease, belonging, or satisfaction—is continuously punctured.

Nate feels emasculated and sidelined by Keru’s financial dominance. His academic disillusionment, coupled with his brother’s dependency, highlights how upward mobility can leave one emotionally adrift.

Ethan, the opportunistic brother, embodies a familiar resentment toward the “one who made it out,” accusing Nate of elitism while seeking his resources. Keru, despite her professional success, finds that no amount of money can insulate her from racism, loneliness, or familial obligation.

Her wealth is not empowering in her relationships—it becomes another source of pressure and another reason for others to depend on her. The neighbors Mircea and Elena further complicate this dynamic.

Their effortless cosmopolitanism, economic comfort, and cultural fluency stand in stark contrast to Keru and Nate’s constant negotiation. What the neighbors project—graceful ease, sophisticated parenting, multilingual confidence—becomes an unattainable standard against which the protagonists measure themselves.

The American dream, often framed as a reward for effort and virtue, is exposed here as a myth that obscures ongoing struggle. Success, rather than being a destination, is shown as another terrain of anxiety—where value is measured, roles are contested, and happiness remains elusive.