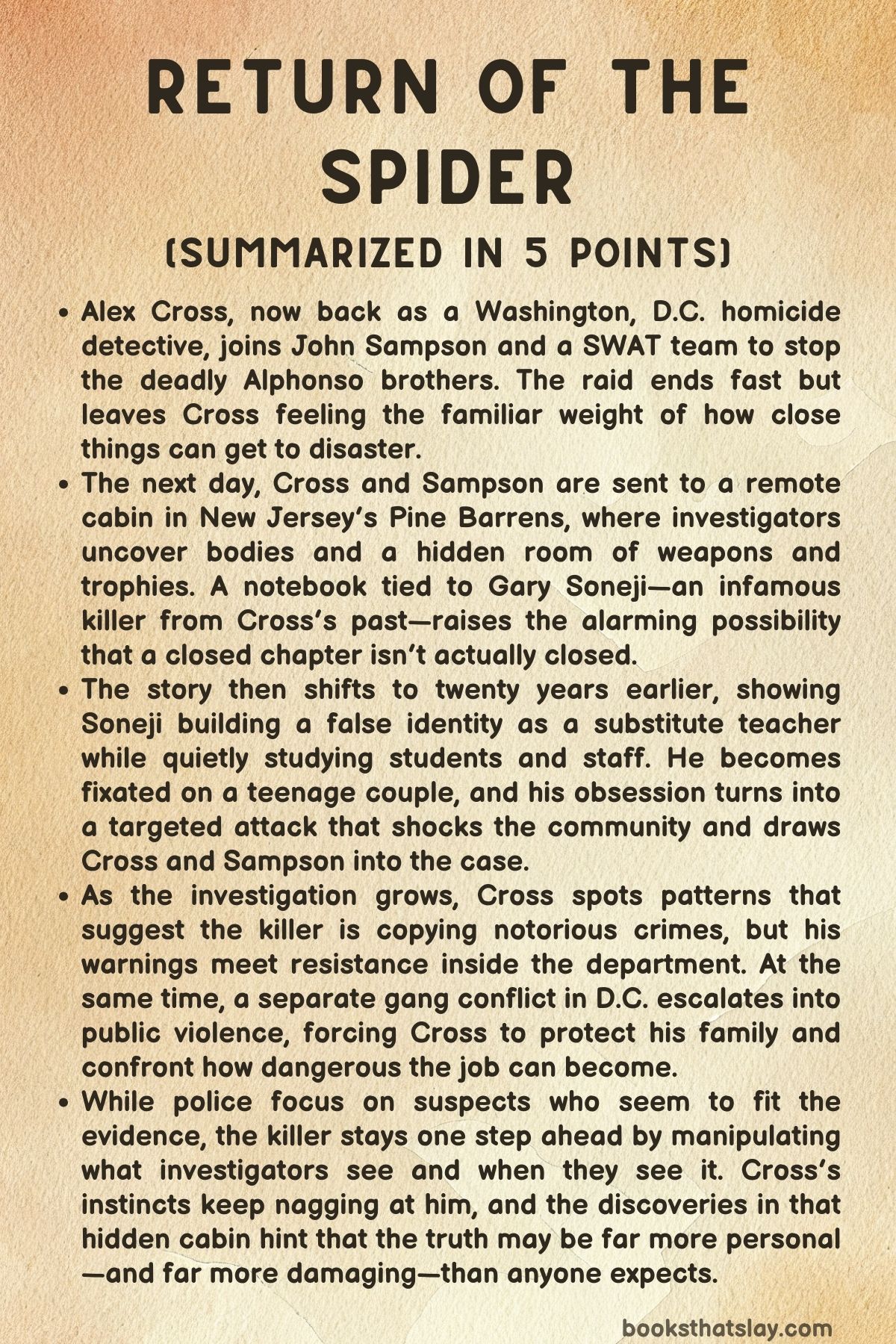

Return of the Spider Summary, Characters and Themes

Return of the Spider by James Patterson is a crime thriller that brings Alex Cross face-to-face with a nightmare he believed was long over. Now back on the job as a Washington, D.C. homicide detective, Cross is pulled into a case that begins with a routine operation and quickly turns into a reckoning.

A hidden cabin, a secret room, and a killer’s private record reopen an old wound: the possibility that Cross’s greatest victory was built on a lie. As past and present collide, Cross must confront what he missed, who paid the price, and what it will take to set it right. It’s the 34th book in the Alex Cross series.

Summary

Alex Cross has returned to active duty in Washington, D.C., balancing police work with the quiet routines of home life. One sweltering May evening, he is at his piano when Detective John Sampson calls with urgent news: the Alphonso brothers, violent meth-fueled bank robbers linked to multiple killings, have been located at an aunt’s old house in District Heights.

Cross grabs his weapon, says goodbye to his family, and joins Sampson as a SWAT unit prepares to move in under the command of Captain Nyla Knight.

The arrest attempt becomes a gun battle almost immediately. The brothers fire first, dropping an officer.

Knight authorizes snipers, and within moments Trevor Alphonso is killed. Nicky Alphonso charges outside, screaming and shooting, and he is taken down as well.

Two women inside the house stumble out unharmed, shaken but alive. Cross and Sampson leave the scene thinking the outcome could have been far worse: two dangerous men are dead, and an officer is wounded but alive.

Cross barely gets a few hours of sleep before another call arrives. His chief orders Cross and Sampson to drive to Batsto, New Jersey, deep in the Pine Barrens, to meet a state police captain and an FBI presence already on site.

When they arrive, the place feels wrong in a way that has nothing to do with the weather or the rotting cabin in the trees. Investigators have uncovered multiple bodies near the property.

The discovery began when a new owner, Adam Brenner, bought the cabin at auction and found a hidden space behind a false wall in the basement. What was inside wasn’t just disturbing—it was personal to Cross.

A notebook bearing the name Gary Soneji has surfaced, tied to a killer Cross once captured and believed dead.

Cross meets Captain Alexander Barthalis and also reconnects with Ned Mahoney, an FBI colleague from years ago. The history between them is uneasy, sharpened by the fact that Soneji was one of the most infamous figures Cross ever hunted.

Soneji, once known as Gary Murphy, escaped custody long ago and was thought to have died in an explosion. The notebook, the cabin’s ownership trail, and the evidence now suggest the story never truly ended.

In the basement, Cross finds the broken wall and steps into a cramped secret room that looks like a museum built by a murderer. There are guns, ropes, knives, restraints, and neatly organized kits labeled with sets of initials.

Shelves hold Polaroids of victims, jewelry, locks of hair, and other trophies. Plastic bins are matched to notebooks, each carefully coded as if the room were part of a catalog.

A black leather journal titled “Profiles in Homicidal Genius, by Gary Soneji” sits among the items like a signature. Reading it, Cross realizes Soneji wasn’t only keeping souvenirs—he was studying famous murderers the way a student studies masters, building his own identity around notoriety and “craft.”

The journal pulls the story back to Cross’s early days in homicide, when he was still learning how quickly a case could turn from tragic to monstrous. Around that time, Soneji is operating under disguises and false identities, moving through schools and communities while watching for targets.

He becomes obsessed with a teenage girl, Abby Howard, and her boyfriend, Conrad Talbot. One night, he follows them to a secluded spot near the Potomac.

Wearing a mask and gloves, he fires through their car window. Conrad dies instantly; Abby is gravely wounded.

As Soneji flees, he spots a bicyclist who has noticed him and left a warning message. Panicked, Soneji hunts the man down and runs him off the path, leaving him critically injured.

Cross and Sampson respond to the scene the next morning. They find the vehicle, Conrad’s body, Abby fighting to survive, and the battered cyclist, a Senate aide named Carl Dennis.

Their supervisor limits their role, assigning senior detectives, but Cross and Sampson keep working angles and asking questions. They visit the school, interview staff and students, and speak to the very man who committed the crime, unaware he’s standing in front of them under an altered appearance and a practiced manner.

At the medical examiner’s office, Cross watches the autopsy and notes details that don’t match a random street shooting. Abby later describes a shadow at the driver’s side window, a masked man raising a pistol in the moonlight.

Cross studies the bullet path and the shooter’s approach, seeing planning in the angles. The ammunition also catches his attention: a .44-caliber round with echoes of an older pattern of killings.

Cross suggests a copycat inspired by notorious cases, but his team treats the idea as speculation. He is warned to fall in line, share information, and stop acting like an outsider.

While Cross struggles to prove himself inside the department, he leans on his family. His wife Maria is pregnant and steadying, reminding him that his value is his mind and his ability to read human behavior.

Cross tries to listen, but the city won’t let him breathe. A second teen is found murdered in a park, tied and beaten.

Gang tensions rise, and an undercover officer, Nancy Donovan, gives them names and warnings, especially about Haitian crew leader Patrice Prince and his cousin Valentine Rodolpho. Pressure builds from above, and Cross and Sampson are pushed to squeeze Rodolpho even when it risks Donovan’s cover.

Violence erupts in broad daylight outside Cross’s church when a black Suburban drives by and opens fire as parishioners exit Mass. Cross shields his grandmother and his young son Damon.

In the chaos, Father Nathan Barry is killed, and Maria is splattered with blood. Sampson believes the attack was meant for them, retaliation for their investigation.

The department shifts into emergency mode, and soon a lead points toward a warehouse in Davidsonville, Maryland.

Cross and Sampson stake out the warehouse in heavy fog and witness a chilling arrival: Donovan is dragged in blindfolded and bound. Pittman orders them to hold until more units arrive, but a large truck pulls in, signaling something bigger.

Then an explosion tears the fence, masked attackers storm the area, and a firefight erupts. Cross and Sampson move in during the chaos, slipping into the warehouse and fighting their way toward Donovan.

They reach Prince’s office zone, only to be captured at gunpoint by Rodolpho—until an unexpected shooter intervenes. The attacker is Guillermo Costa, tied to a rival crew and driven by revenge.

In a swift, brutal exchange, Costa kills Rodolpho and Prince after forcing admissions about earlier murders and the location of heroin hidden in industrial drums. Police flood in, and Donovan survives.

All the while, Soneji continues killing under cover of normal life. He kidnaps a woman named Bunny Maddox, takes her to his Pine Barrens cabin, and murders her after she briefly escapes.

Later, as investigators chase other suspects, he revels in misdirection and plants evidence to steer police toward two ex-cons, Eamon Diggs and Harold Beech. The evidence appears convincing, and the department celebrates arrests as a major win.

Cross has doubts about how sloppy parts of the setup look, but lab confirmations and department momentum bury his unease. Life moves forward: Maria gives birth to their daughter, and Cross tries to believe the nightmare has been contained.

Years later, standing in that hidden room in New Jersey, Cross reads the truth in Soneji’s own words. The diary lists victims and reveals the frame job in detail.

Diggs died in custody insisting he was innocent. Beech remains imprisoned.

Cross is devastated by what it means: his reputation, his career milestones, and the official record of justice were shaped by a killer’s manipulation. He and Sampson visit Beech in a high-security prison with Beech’s former lawyer and tell him what they’ve discovered.

Beech breaks down, caught between disbelief and desperate hope. Cross leaves determined to atone—by clearing the innocent, telling Diggs’s family what happened, and refusing to let Soneji’s legacy remain sealed behind a false wall.

Characters

Alex Cross

In Return of the spider, Alex Cross is the story’s moral and emotional center: a seasoned investigator whose instincts are sharp, but whose deepest conflict is internal. In the present-day frame, he’s controlled, capable, and respected enough to be pulled into high-level incidents, yet the discovery in the Pine Barrens yanks him back into the most painful professional mistake of his life.

Cross’s defining trait here is conscience—he doesn’t just want to catch killers, he wants the truth to be clean, the story to be accurate, and the justice to land on the right person. That integrity becomes his burden when he realizes Gary Soneji manipulated him into helping ruin innocent lives, and the guilt doesn’t stay abstract: it bleeds into how he views his career, his identity, and the safety of his family.

What makes Cross compelling is that he’s not portrayed as flawless; his ambition, impatience, and early-career insecurity help create the conditions for Soneji’s deception, and the book forces him to confront that the cost of being wrong is measured in human lives.

John Sampson

John Sampson functions as Cross’s stabilizer and counterweight—less introspective on the surface, but deeply loyal and strategically grounded. Where Cross spirals into self-blame and psychological interpretation, Sampson tends to focus on the next actionable move, the immediate threat, and the practical realities of police work.

That dynamic makes him essential in both timelines: he’s the partner who helps Cross keep moving when the emotional weight could freeze him. Sampson also represents a form of steadfast morality that doesn’t require constant self-interrogation; he wants justice, but he also understands institutions, teamwork, and survival inside a political workplace.

His protective instincts show most clearly when danger turns personal, and his commitment to Cross doesn’t waver even when Cross’s choices strain professional relationships. In the end, Sampson isn’t just “the sidekick”—he’s the witness to Cross’s fallibility and the person who stands with him in the uncomfortable work of making things right.

Gary Soneji

Gary Soneji is depicted as a predator who craves authorship—he doesn’t merely kill, he wants to be studied, remembered, ranked, and imitated. His “art” is control: disguises, false identities, staged evidence, and psychological games designed to turn law enforcement into unwilling collaborators.

What’s chilling is how Soneji’s self-image depends on comparison; he measures himself against notorious killers and frames his violence as an education in “mastery,” which lets him rationalize cruelty as craft. He is also emotionally small beneath the grandiosity—easily irritated by slights, resentful of ordinary domestic life, and fueled by grievance as much as ambition.

The notebook and labeled trophies reveal a mind that organizes human suffering into categories and keepsakes, turning victims into proof of status. Soneji’s greatest weapon isn’t a gun or rope; it’s his ability to manipulate narrative so convincingly that good people build careers on lies he planted.

Bree Cross

Bree appears in the present timeline as Cross’s anchor to everyday life and normalcy, highlighting what’s at stake when his work drags danger home. Her role is understated but important: she represents the domestic world Cross tries to protect and the emotional cost of a partner who disappears into violent crises without warning.

Bree’s presence also emphasizes Cross’s dual identity—family man and hunter of predators—and the tension between those roles. Even when she’s not in the center of the action, she is part of the silent calculus behind Cross’s decisions: every risk he takes has a face waiting at home.

Nana Mama

Nana Mama embodies the family’s moral backbone, offering Cross a kind of wisdom that is both tender and unsparing. She doesn’t excuse his mistakes, but she refuses to let him collapse into self-punishment, redirecting him toward repair rather than despair.

In a story filled with institutions that judge competence and outcomes, Nana Mama insists on character and responsibility: if Cross has been wrong, then the next right act matters more than his pride. Her presence also grounds the narrative culturally and emotionally, making Cross’s home life feel like more than a backdrop—it’s a refuge with its own values.

She becomes especially crucial when Cross’s guilt threatens to rewrite his entire life as a fraud; she reframes redemption as work, not a feeling.

Captain Nyla Knight

Captain Nyla Knight is introduced as decisive and operationally formidable, a leader who carries the burden of life-and-death calls in real time. During the Alphonso standoff, she’s not romanticized; she’s professional, pragmatic, and willing to authorize lethal force to stop imminent threat.

Her function in the story is to contrast clean, immediate outcomes with the messier moral terrain of the Soneji case—here, the bad guys are clearly dangerous, the response is controlled, and the result is unambiguous. Knight’s competence underscores that Cross’s later torment isn’t about general police work being impossible; it’s about how uniquely corrosive Soneji’s manipulations are.

Kane

Kane, as Cross’s superior in the present timeline, represents urgency and institutional pressure: the system pulls Cross away from family and local cases the moment a bigger, politically charged discovery appears. His role is less about personality and more about function—he is the mechanism that launches the Pine Barrens investigation and signals that Soneji’s shadow is now a multi-agency crisis.

Kane’s abrupt orders also reinforce how Cross’s life is shaped by other people’s alarms, even when the consequences land most heavily on him.

Trevor Alphonso

Trevor Alphonso is portrayed primarily through threat and violence rather than interiority, serving as a symbol of immediate, chaotic criminal danger. His meth-fueled brutality and willingness to open fire first place him beyond negotiation, and his death by sniper emphasizes how quickly such confrontations can turn fatal.

In narrative terms, he helps establish the book’s high-stakes tone and reminds the reader that Cross’s world contains both impulsive street violence and the colder, more methodical evil of Soneji.

Nicky Alphonso

Nicky Alphonso mirrors Trevor as a second embodiment of reckless aggression, but his frantic charge out of the house adds a note of desperation—violence as panic as much as intent. His end is swift, and the scene frames him as a danger that forces officers into split-second decisions.

Together with Trevor, Nicky helps open the story with a “contained” resolution, which makes the later unraveling of the Soneji frame-up feel even more destabilizing.

Captain Alexander Barthalis

Captain Alexander Barthalis serves as the local authority who brings Cross into a crime scene that feels both secretive and historic. He’s presented as methodical and credible, the kind of professional who understands that what’s in the Pine Barrens is bigger than one jurisdiction.

Barthalis’s significance lies in how he legitimizes the horror: the graves, the hidden room, and the evidence aren’t rumors or folklore—they are documented facts demanding a serious response. He becomes part of the web of institutions converging around Soneji’s legacy.

Ned Mahoney

Ned Mahoney represents Cross’s past in the FBI and functions like a bridge between Cross’s earlier career identity and his present-day reckoning. His presence signals that this case is not just personal trauma—it’s a professional crisis with federal implications and old reputations on the line.

Mahoney also acts as a witness to Cross’s realization, which matters because Cross’s guilt needs an external reality check; it can’t stay locked inside his mind. By being there when the truth surfaces, Mahoney helps turn Cross’s private horror into a shared obligation to correct the record.

Adam Brenner

Adam Brenner is the accidental catalyst: a new owner whose mundane purchase exposes extraordinary evil. He doesn’t drive the narrative emotionally, but his role is essential because it shows how the past resurfaces through chance, not justice.

Brenner’s discovery underscores a theme in Return of the spider: evil can hide in ordinary places for years, waiting for a broken wall, a curious hand, or a minor decision to bring it back into daylight. He is a reminder that consequences outlive perpetrators and that history can be stored, literally, behind false construction.

Abby Howard

Abby Howard is portrayed as both victim and vital witness, carrying trauma that becomes evidence. Her survival forces the investigation into a more intimate register: this isn’t only about a body and ballistics, it’s about a teenager trying to describe a masked figure in moonlight while her life has been shattered.

Abby also serves as an object of Soneji’s fixation, which is important because the story frames his violence as obsession-driven rather than opportunistic. Her relationship with Conrad gives the tragedy emotional texture, and her interview scenes highlight Cross’s empathy and psychological skill—he’s not just extracting facts, he’s trying to help a wounded person endure.

Conrad Talbot

Conrad Talbot functions as the story’s early symbol of innocence targeted for spectacle. He’s depicted as socially visible and loved, which intensifies the public pressure and institutional urgency around the case.

Conrad’s death is also structurally important: it becomes a “signature” event that Cross interprets as potentially patterned, pushing him toward the copycat theory that others dismiss. In effect, Conrad is one of the first stones in the domino line—his murder sets Cross on a path that eventually intersects with Soneji’s long game.

Tony Miller

Tony Miller’s murder grounds the narrative in a different kind of violence: local, gang-related, and rooted in neighborhood power. His death confronts Cross early in his career with senselessness and grief that can’t be neatly profiled into a mastermind’s scheme.

Tony’s funeral and the emotional toll it takes on Cross help explain why Cross is both driven and vulnerable to pressure—he wants to make meaning and stop the damage fast. Tony also ties into the broader gang storyline that shows Cross working multiple fronts at once, amplifying fatigue and decision strain.

Carl Dennis

Carl Dennis, the bicyclist and Senate aide, is a brief presence but thematically sharp: he’s an ordinary citizen whose attempt to intervene triggers lethal retaliation. His death illustrates Soneji’s volatility—when control is threatened, he escalates instantly.

Carl also expands the harm radius beyond the “chosen” targets, showing that proximity to evil is enough to become a victim. In investigative terms, his case also increases the complexity and public sensitivity of the crime.

Chief Pittman

Chief Pittman embodies the institution’s hierarchy, politics, and impatience, often colliding with Cross’s instincts and independence. He’s not presented as purely antagonistic; rather, he’s a leader trying to manage media pressure, jurisdictional boundaries, and internal resentment, and Cross becomes a liability when he acts outside protocol.

Pittman’s skepticism toward the copycat theory reveals a core tension: policing often prefers concrete evidence over interpretive leaps, even when the leap might be correct. His decisions also show how bureaucracy can distort truth-seeking, especially when image management becomes part of the mission.

Pittman’s role highlights how Soneji’s manipulation succeeds partly because the system rewards closure and punishes uncertainty.

Detectives Corina Diehl and Edgar Kurtz

Corina Diehl and Edgar Kurtz function as the voice of procedural discipline and team structure, reinforcing that Cross can’t operate as a lone savant inside a department that depends on coordination. Their warnings about communication and respect reveal workplace friction around Cross’s rapid rise and unconventional thinking.

They also represent the social reality of institutions: even good instincts can be undermined if colleagues feel excluded or embarrassed. In a story about a killer who exploits gaps and ego, Diehl and Kurtz show that internal cohesion is not a soft value—it is part of investigative survival.

Dr. Emily Chin

Dr. Emily Chin stands for forensic clarity—the calm, empirical counterpoint to theory and intuition. Her autopsy findings provide the concrete details that fuel Cross’s suspicions, especially the angle and behavior implied by the bullet trajectory.

She is significant because she demonstrates how truth is assembled from physical facts, not just hunches, and her work becomes a foundation Cross builds on even when others dismiss his conclusions. In a narrative thick with deception, her role is a reminder that bodies don’t lie, even when people do.

Maria Cross

Maria Cross is a luminous presence precisely because she is both ordinary and extraordinary: a loving partner grounded in service, whose warmth makes the violence around Cross feel more tragic. She functions as Cross’s emotional refuge, but also as his counselor—she encourages him to trust his psychological insight while staying anchored to reality.

Their relationship scenes reveal Cross’s vulnerability and hunger for reassurance, clarifying how pressure at work can threaten his confidence. Maria’s pregnancy and later motherhood intensify the stakes, turning danger into something that could rupture the most sacred part of Cross’s life.

She also represents a different model of “helping”: where Cross pursues justice through pursuit and confrontation, Maria does it through care, presence, and community work.

Damon Cross

Damon is portrayed through Cross’s gaze as innocence worth protecting, a quiet emotional compass that reminds Cross why he endures the brutality of his job. Moments of Cross looking in on Damon emphasize gratitude and fear in equal measure, especially as violence creeps closer to the family sphere.

Damon’s existence also deepens Cross’s guilt later: if Cross believes his career was built on lies, then the stability he provided his child becomes psychologically complicated. Damon doesn’t need extensive dialogue to matter; his role is symbolic weight made personal.

Janelle “Jannie” Cross

Janelle’s birth represents renewal and joy amid escalating darkness, a reminder that life continues even when horror persists. Her arrival also heightens the emotional cruelty of Soneji’s shadow: while Cross’s family grows, the truth about past murders and wrongful convictions festers unseen.

Jannie functions as a symbol of hope that Cross is desperate not to contaminate with his professional sins and enemies.

Headmaster Charles Pendleton Little

Charles Pendleton Little is portrayed as vain and status-driven, which makes him easy for Soneji to manipulate. He represents institutions that mistake confidence for credibility, especially when the “right” cultural signals are performed.

The nondisclosure agreement and the school’s elite environment intensify the stakes of Soneji’s access—this is a place where power and publicity intersect, and Soneji recognizes it as a platform for notoriety. Little is not evil, but his priorities create vulnerability, showing how prestige can become a security blind spot.

Agent Jezzie Flanagan

Jezzie Flanagan appears as a competent federal presence within the school-related aftermath, adding official weight and procedural reach. Her significance is partly dramatic irony: she delivers or participates in information exchange in a space where the killer is hiding in plain sight.

Jezzie represents the broader system trying to manage risk around high-profile families, and her presence highlights how Soneji’s deception slips past multiple layers of authority.

Nancy Donovan

Nancy Donovan is depicted as brave and deeply embedded, an undercover officer operating in proximity to lethal gang politics. She brings street intelligence that Cross and Sampson can’t access directly, but her position also makes her vulnerable to institutional impatience—when leadership pushes too hard, she loses access and safety.

Donovan’s kidnapping and restraint reveal the brutal consequences of misaligned priorities and the fragility of undercover work. She also functions as a catalyst for the warehouse confrontation, where multiple violent agendas collide.

Patrice Prince

Patrice Prince is presented as a gang leader whose power is maintained through intimidation and violence, the kind of criminal figure who turns neighborhoods into battlefields. His response to pressure is escalation, culminating in public terror that demonstrates how gang conflict can spill into sacred community spaces.

Prince is significant because he shows a different face of evil from Soneji: less theatrical, more territorial, but still devastating. His end at Guillermo Costa’s hands underscores how criminal ecosystems devour themselves, often bypassing legal justice entirely.

Valentine Rodolpho

Valentine Rodolpho is portrayed as slippery and performative—someone who can present himself as community-minded while remaining entangled in lethal operations. His role in surveillance scenes highlights the difficulty of distinguishing genuine reform from strategic camouflage, especially when law enforcement’s information is partial.

Rodolpho’s eventual death is abrupt and violent, reinforcing that in this world, moral narratives are often decided by whoever holds a weapon in the moment, not by courts or truth.

Guillermo Costa

Guillermo Costa is one of the story’s most morally complicated figures: a reformed ex-con positioned as a community figure, yet capable of swift, surgical violence fueled by personal loss. His revenge attack in the warehouse feels like a vigilante eruption inside a law-enforcement operation, destabilizing the neat boundary between “criminal” and “ally.” Costa’s actions expose truths the police sought—names, responsibility, locations—but he extracts them through execution, not due process.

He embodies the theme that justice and vengeance can look similar in motion while being fundamentally different in meaning. Costa’s presence forces Cross and Sampson into an uncomfortable reality: sometimes the answers arrive through methods they cannot endorse.

Father Nathan Barry

Father Nathan Barry’s death is a stark symbol of community innocence shattered by targeted violence. The church setting amplifies the horror because it violates an assumed sanctuary, turning a place of moral refuge into a crime scene.

His loss also personalizes the gang storyline for Cross’s family, transforming “case pressure” into spiritual and emotional devastation. Father Barry functions as a reminder that violence rarely confines itself to the guilty; it tears through bystanders and the good.

Missy Murphy

Missy Murphy is positioned as the ordinary domestic counterpart to Soneji’s hidden monstrosity, which makes her scenes unsettling even when they seem mundane. She becomes a mirror that reflects Soneji’s contempt for normal accountability—her social expectations, frustrations, and public scolding register to him as intolerable control.

Missy’s role illustrates that Soneji’s violence isn’t only sexual or predatory; it’s also punitive, rooted in resentment toward anyone who limits his fantasy of superiority. She exists in tragic proximity to a killer who can mimic tenderness while privately rehearsing replacement and punishment.

Bunny Maddox

Bunny Maddox is portrayed with heartbreaking clarity: a working mother with routines and responsibilities whose life is hijacked by Soneji’s stalking and abduction. Her brief acts of resistance, including striking him and attempting escape, highlight her courage and humanity, making her murder feel especially cruel.

Bunny also functions as a key link in the investigation through her disappearance details and the white-van trail. Her story shows Soneji’s methodical cruelty—he doesn’t only kill; he stages fear, isolation, and false hope as part of the experience.

Calvin Maddox

Calvin Maddox serves as the grieving family witness who provides practical details that push the case forward. His observations about the van and the abandoned car contents give the investigation a tangible direction and emphasize how families become accidental investigators when institutions arrive too late.

Calvin’s role also reinforces the human cost beyond headlines: victims have networks, histories, and people who will never be the same.

Detective Kelsey Girard

Kelsey Girard functions as the local professional who recognizes pattern and reaches outward, a reminder that good policing often depends on cross-jurisdiction communication. Her alert about a kidnapping tied to an older white van is the kind of detail that can vanish in bureaucratic silos, but she acts instead of waiting.

She represents competence without ego—focused on connecting dots rather than claiming credit.

Eamon Diggs

Eamon Diggs is a tragic figure shaped by the story’s central deception: a man caught in the machinery of a frame-up convincing enough to satisfy institutions hungry for closure. His explanations sound absurd on the surface, which makes it easier for authorities to dismiss him, and that vulnerability becomes part of Soneji’s strategy.

Diggs’s death in custody while proclaiming innocence crystallizes the book’s moral indictment: wrongful certainty kills in slow motion. He becomes one of the narrative’s most haunting consequences, not because he is noble, but because he is human and expendable to a system that believed it had “solved” the problem.

Harold Beech

Harold Beech is written as anxious and evasive, a man with a criminal past whose credibility is brittle and whose fear reads as guilt. That ambiguity makes him an ideal target for Soneji’s misdirection and for investigators eager to stop the nightmare.

Beech’s later emotional response in prison—grief, disbelief, and fragile hope—reframes him from “suspect” into “victim of the system,” emphasizing how easily a life can be sealed behind bars by manufactured certainty. His character carries the story’s theme of stolen time: even if released, the years remain taken.

Ryan Davis

Ryan Davis, as Beech’s former lawyer, represents the legal pathway toward repair—procedure used as a tool for truth rather than punishment. His presence signals that Cross’s atonement must become more than personal guilt; it has to translate into action that can stand in court and bureaucracy.

Davis also provides a reality check: correcting injustice requires evidence, documentation, and persistence, not just confession.

Sandy Ravisky

Sandy Ravisky is used to display Soneji’s capacity for indirect murder—killing by sabotage rather than confrontation. Her death, along with her family’s, underscores his indifference to collateral damage and his willingness to let “accident” do the work of violence.

Sandy’s role is brief, but it expands the portrait of Soneji from stalker-killer into architect of catastrophe, someone who weaponizes everyday systems like a vehicle’s mechanics.

Cheryl Lynn Wise

Cheryl Lynn Wise is presented as Soneji’s next fixation, which is significant less for what she does and more for what she represents to him: youth, vulnerability, and a new canvas for notoriety. Her presence highlights Soneji’s predatory pattern of choosing targets within spaces of trust, especially schools.

Cheryl symbolizes the future harm that persists whenever a predator remains undetected and empowered.

Cynthia Owens

Cynthia Owens is the embodiment of random vulnerability—someone who simply asks for help and becomes prey. Her murder demonstrates how Soneji doesn’t require elaborate justification; sometimes opportunity is enough, and the thrill of dominance is the point.

Cynthia’s death also reinforces the Pine Barrens as a landscape of hidden violence, where isolation becomes a weapon. She is one of the names that turns the notebook from a creepy artifact into a ledger of real, stolen lives.

Hector Munoz

Hector Munoz appears in Cross and Maria’s origin story, serving as the context that first reveals Maria’s compassion and Cross’s attraction to it. He represents the kind of societal violence that drives both of them into service—Maria through social work, Cross through policing.

Hector’s role is important because it shows Cross’s early motivation wasn’t glory; it was drawn from witnessing harm and wanting to respond with skill and empathy.

Themes

The weight of unfinished history and professional guilt

Alex Cross walks into a present-day crime scene and finds his own past waiting for him in a hidden room: labeled weapons, trophies, Polaroids, and a notebook that carries Gary Soneji’s voice across decades. That discovery turns policing into something more intimate than procedure, because it forces Cross to confront how a single case can keep shaping every decision afterward.

The story treats memory as active pressure, not background detail. Cross is not only tracking a murderer; he is tracking the consequences of what he once believed was closed and solved.

When the diary reveals that the wrong men were blamed and punished, the shock is not just evidentiary. It is moral injury: the realization that good intentions, confidence, and institutional momentum can still produce harm that cannot be undone.

Cross’s pride in his work becomes complicated because the achievements that built his reputation sit beside an ugly truth that he helped validate. Even the relief of past “victories” is contaminated, and the case turns into a reckoning with how easily certainty can become a trap.

The narrative also shows how guilt behaves inside an experienced investigator: it does not always look like panic or collapse. It can look like restlessness, hyperfocus, and the refusal to accept neat resolutions.

Cross’s unease after the arrests of Diggs and Beech is a quiet example of conscience resisting the desire for closure. Later, when he speaks to Beech in prison and promises to fight for his release, the theme shifts from regret to responsibility.

The story treats atonement as action rather than self-punishment: admitting error, naming what went wrong, and accepting that justice includes correcting the system’s mistakes, not only hunting the next offender.

The criminal hunger for recognition and self-made mythology

Gary Soneji is presented as someone who commits violence not only to dominate victims, but to manufacture a legacy. His notebook frames murder as a craft and himself as a student of famous killers, which shows a need to be seen, studied, and remembered.

That mindset turns the crimes into performances with an audience in mind: police, media, future “criminologists,” and the society he imagines will eventually grant him status. He does not merely kill; he curates evidence, labels tools, keeps trophies, and documents his own thinking so that his identity can survive him.

The story highlights how that desire for recognition shapes his methods. He seeks environments that offer access to symbolic power—elite schools, wealthy families, famous connections—because notoriety matters as much as physical control.

His disguises and assumed names are not just tactics to evade capture; they are costumes in a private theater where he plays multiple roles: ordinary substitute teacher, family man, predator, mastermind. Even his domestic life becomes part of the mask, which makes the theme unsettling: the persona is not something separate from him, it is something he refines and protects.

The narrative also emphasizes his contempt for ordinary emotional limits. When a child dies in the staged crash, he registers irritation and exhilaration, not sorrow.

That reaction is crucial to the theme because it shows how his self-mythology replaces empathy. He treats unintended consequences as proof of his transformation into something “greater,” which is a twisted version of artistic ambition.

His fixation on “masters” and on copying patterns like Son of Sam suggests a craving to join a canon, as if murder is an exclusive club where the price of membership is human life. The story’s horror comes partly from how deliberate and literate that craving is: he studies, compares, and evaluates, turning real suffering into material for self-promotion.

In Return of the Spider, the killer’s greatest attachment is not to a person but to an image of himself that must keep growing, even if it requires new bodies to feed it.

The fragility of justice inside institutions that crave closure

The investigation repeatedly shows how justice can be bent by impatience, hierarchy, and public pressure. Cross and Sampson are working in systems where leadership wants answers quickly, media narratives need to be managed, and departmental politics shape who gets heard.

Cross’s early instincts about pattern and intent are treated as “speculation” by superiors who worry about reputations and chain of command. That tension is not just workplace drama; it exposes a structural vulnerability: when the institution prioritizes stability and appearance, it can push aside the slow discomfort of uncertainty.

The arrests of Diggs and Beech become a central example of how closure can be manufactured. Evidence is presented as airtight, celebrations follow, and the case is treated as resolved—yet the story later reveals that this confidence was partly engineered by Soneji’s framing.

The theme is not that police are careless by nature, but that the machinery of law enforcement can be exploited when it wants an ending more than it wants the truth. Soneji understands procedures well enough to plant misdirection that fits what investigators expect to see.

The narrative suggests that “reasonable assumptions” are dangerous when they become the basis for certainty, because a clever offender can design evidence that flatters those assumptions. The presence of jurisdictional boundaries also complicates justice.

Cross responds to a pattern that crosses lines, but he is reprimanded for stepping into another case’s territory, showing how rules meant to organize work can sometimes block recognition of broader threats. Internal resentment toward Cross’s rapid promotion adds another layer: status and ego become background forces that decide which ideas gain traction.

Even when Cross is right about a copycat pattern, the system’s social dynamics can silence him. By the time the truth emerges, the cost is huge: years of imprisonment for an innocent man, death in custody for another, and an investigative record built on an error that cannot be neatly corrected.

The story frames justice as something that must be actively protected from institutional habits—especially the habit of treating resolution as proof. Real justice requires the willingness to reopen what feels settled, to accept embarrassment, and to prioritize the human consequences of mistakes over the comfort of official success.

Family as sanctuary, motivation, and a point of exposure

Cross’s home life is not presented as a break from the darkness; it is one of the central engines of his choices and his vulnerability. Music at the piano, meals prepared by Nana Mama, the warmth of Maria’s presence, and the small rituals around Damon create a sense of stability that contrasts with the chaos of the cases.

That stability matters because it shows what Cross is protecting, and why he keeps returning to work even when it costs him sleep, safety, and peace. Family is also where his insecurities surface most clearly.

With Maria, he admits doubts about his experience and fears about being judged by colleagues, and her reassurance becomes a kind of ethical compass: use imagination, but keep it grounded in reality. That advice is not just affectionate; it shapes how he approaches evidence and pattern recognition, suggesting that emotional support can translate into investigative clarity.

At the same time, the story treats family as a point of exposure. The shooting outside the church turns public violence into personal terror, with Cross shielding his grandmother and child while a priest is killed and Maria is left traumatized.

That moment collapses the boundary between professional danger and domestic safety. It also shows how criminals can weaponize proximity: pressure Cross and Sampson, and the people around them bleed.

The narrative later connects these experiences to longer-term loss, making the theme even sharper. Family becomes both the reason Cross persists and the reason the job can never be “just a job.” His decisions are filtered through what they might cost at home, yet he cannot fully withdraw because the work is tied to the safety of the same community his family lives in.

The arrival of his daughter brings joy, but it also raises the emotional stakes of every risk he takes. This theme deepens the story’s moral tension: courage is not portrayed as fearlessness, but as continuing to act while aware of what could be taken away.

In Return of the Spider, family love is a source of resilience, but also a reminder that every investigative failure is not abstract—it can echo into the most private parts of a life.

Cycles of violence across social worlds and the illusion of separate threats

The narrative moves through multiple forms of violence—gang retaliation, targeted shootings, serial predation, copycat patterns—and shows how these threats coexist in the same geographic and moral space. Teenagers are killed for resisting gang recruitment, a church gathering becomes a shooting scene, and affluent school corridors hide a predator using respectability as camouflage.

The theme here is that violence is not contained within one “type” of crime, and treating it as separate categories can lead to blind spots. Cross and Sampson are pulled between gang investigations and serial murders, and the constant switching reflects how real cities experience harm: layered, overlapping, and often linked by the same pressures of drugs, status, and power.

The Haitian gang storyline highlights a kind of violence that is communal and strategic—intimidation, retaliation, public messaging—while Soneji’s violence is private and ritualized, shaped by fantasy and control. Yet the story does not let these feel like unrelated worlds.

Both rely on fear, both exploit predictable responses, and both create collateral damage that spreads outward to families and communities. The theme also points to how authority responds differently depending on the social context.

Gang violence is approached with surveillance, informants, and tactical raids; serial violence triggers forensic focus, profiling, and media attention. That difference can create a false sense that one domain is “street crime” and the other is “exceptional evil,” when in reality both are part of the same ecosystem of vulnerability.

The copycat dimension makes this even more pointed. When Cross identifies echoes of Son of Sam, the story shows how cultural memory of famous murders can inspire new offenders and confuse investigations.

Patterns become both a tool for investigators and a weapon for killers who want to manipulate expectations. The existence of a hidden cache that references multiple notorious killers suggests that violent “styles” can be studied and replicated, turning past crimes into templates for future ones.

The result is a cycle: notorious cases generate cultural scripts; those scripts create new crimes; new crimes renew fear and attention; and the cycle continues. The theme ultimately argues that violence is adaptive.

It shifts settings, changes masks, and borrows old methods, which means communities and institutions cannot rely on rigid assumptions about where danger comes from or what it looks like.

Accountability and redemption as lived practice rather than a final victory

Once Cross learns the truth about Soneji’s framing, the story refuses to treat that revelation as a plot twist that ends the emotional problem. Instead, it turns into a question of what accountability looks like when harm has already been done.

Cross does not get to erase the past by catching the “real” killer; he has to face the human cost of the wrong convictions and his role in allowing them to stand. The visit to Beech in prison is central because it shifts the idea of justice away from punishment and toward repair.

Beech is not presented as a symbol; he is a person with years stolen from him, and the scene forces Cross and Sampson to confront the gap between legal outcomes and moral truth. The theme also acknowledges how difficult redemption is in a professional identity built on competence.

For a detective, being wrong is not only embarrassing—it can be catastrophic. Cross’s fear that his career was “built on lies” shows how accountability can threaten the very story a person tells about their life.

Nana Mama’s response reframes redemption as responsibility: not denying the past, not drowning in shame, but doing the work that the truth demands. That response matters because it challenges the common crime-fiction fantasy that catching the villain restores order.

Here, order is not restored; it is rebuilt imperfectly through acts like telling a dead man’s family the truth, pursuing release and reparations, and accepting the long shadow of earlier decisions. The theme also highlights how accountability must resist self-centeredness.

Cross could make the revelation about his own suffering, but the narrative pushes him to center the innocent men and the victims whose cases were distorted by Soneji’s scheme. Redemption is framed as outward-facing: repair what can be repaired, name what cannot, and keep pursuing truth even when it hurts personal pride.

In Return of the Spider, the pursuit of justice is not a single finish line. It is a repeated choice to correct errors, confront uncomfortable facts, and treat “doing the right thing” as a sustained practice rather than a moment of triumph.