River Sing Me Home Summary, Characters and Themes

River Sing Me Home by Eleanor Shearer is a powerful debut novel set in the British-colonized Caribbean during the aftermath of slavery’s abolition in 1833. The story follows Rachel, a resilient woman who, after escaping her plantation, embarks on a journey across Barbados, British Guiana, and Trinidad in search of her lost children.

Her quest reveals the deep scars left by slavery and the profound yearning for freedom, identity, and family. Blending history and heart, Shearer explores themes of liberation, survival, and the unbreakable bond between mother and child in a gripping and emotionally charged narrative.

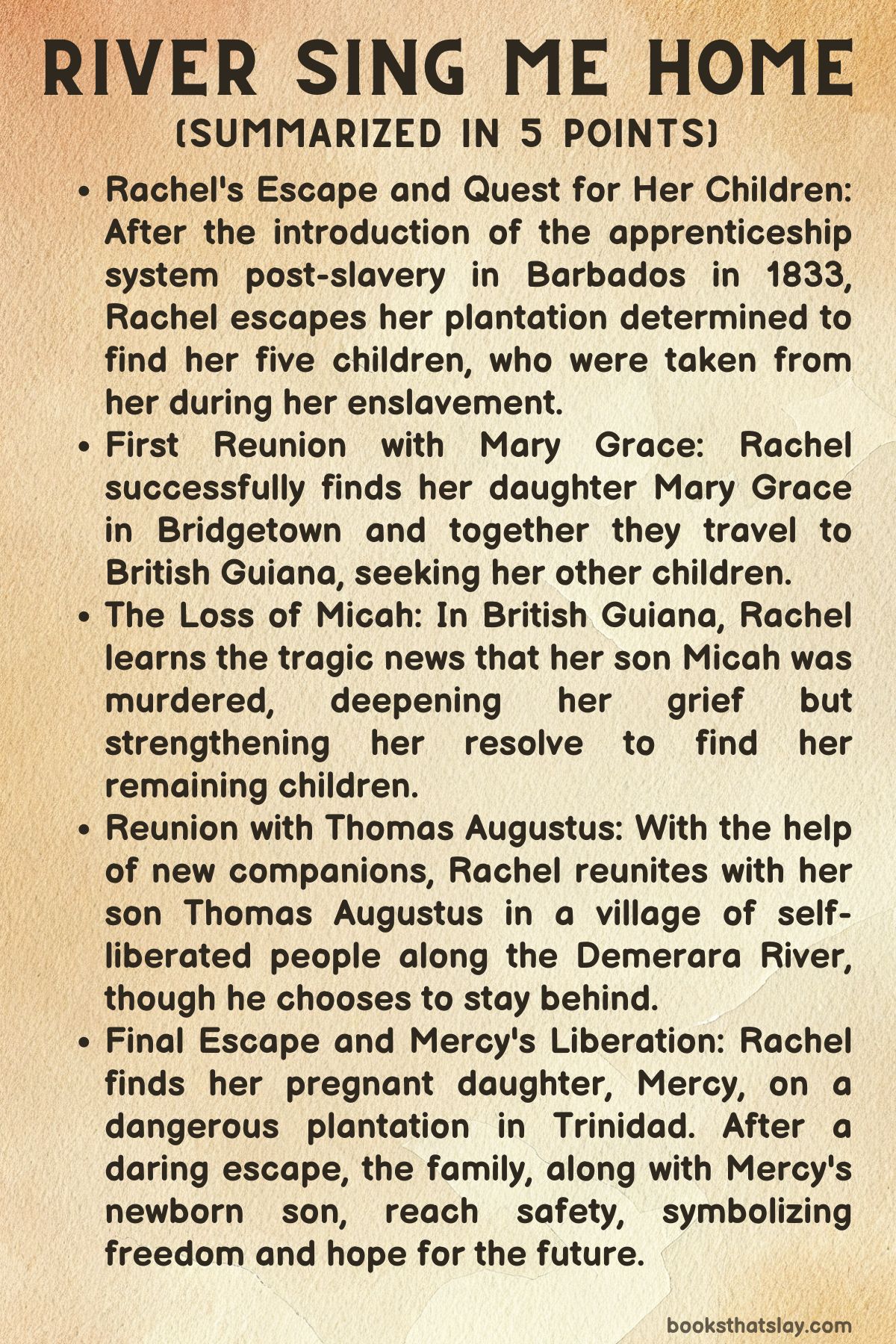

Summary

Rachel’s journey begins in the dense forests of Barbados in 1833, shortly after the Slavery Abolition Act is introduced. Although the law is meant to free enslaved people, it implements an apprenticeship system that keeps them bound to plantations for six more years.

Refusing this new form of bondage, Rachel escapes from Providence plantation, determined to find the children that were torn from her during her years of enslavement. Her first stop is Bridgetown, where she meets Mama B, an elderly woman who aids those seeking freedom.

Mama B shares with Rachel her wisdom about the interconnectedness of all living things, setting Rachel on her path of healing and reunion.

Rachel’s first success is finding her daughter, Mary Grace, who works as a servant in a small clothing shop.

The shop owners, Elvira and Joseph Armstrong, prove to be kind employers, allowing Rachel to work alongside her daughter. Through their generosity, Rachel saves enough money to travel to British Guiana, where she hopes to find her other children.

On this journey, she befriends a man known as Nobody, who becomes a loyal companion to Rachel and Mary Grace.

In British Guiana, Rachel secures work in a tavern run by the harsh Tobias Beaumont. She befriends Albert, another enslaved man, and soon learns of a man named Braithwaite, who may be connected to her son Micah’s fate.

With Albert’s help, Rachel finds Braithwaite’s plantation, where she meets Orion, a man who knew Micah. Orion delivers devastating news—Micah was killed in an act of resistance.

Despite her heartbreak, Rachel presses on, now intent on finding her son Thomas Augustus, who has earned a reputation for escaping slavery. Orion hints that Thomas might be hiding near the Demerara River.

Gathering her companions, Rachel navigates the river with the help of Nuno, a young boy with local knowledge.

Along the way, they encounter Indigenous people who initially view them with suspicion but ultimately help them after Nuno explains their mission. Rachel’s perseverance pays off when they find a village of self-liberated people, and Thomas is among them.

Though their reunion is joyous, Rachel knows her journey is not over—she still has more children to find.

Next, Rachel travels to Trinidad, where she discovers her daughter Cherry Jane living a new life, passing as the daughter of a wealthy family.

Although Cherry Jane’s coldness initially hurts Rachel, the death of Micah brings them together in shared grief. However, Cherry Jane chooses to stay in her adopted life, leaving Rachel with a lead on Mercy, her last remaining child.

Rachel’s search for Mercy leads her to a plantation ruled by the brutal overseer Thornhill. Mercy, now heavily pregnant, warns Rachel of the danger, but Rachel refuses to leave her daughter behind. After a daring escape, Rachel, Mercy, Nobody, and Mary Grace flee to safety.

During their escape, Mercy gives birth to a son named Micah. The group finally reaches a settlement where they can begin anew. United at last, they find solace in each other’s presence, and Mary Grace’s voice, silent for years, is restored as she sings a song of freedom.

Characters

Rachel

Rachel is the protagonist of River Sing Me Home, a fiercely determined mother who seeks to reunite with her lost children after fleeing the Providence plantation in Barbados. Her journey is motivated by an intense maternal instinct, resilience, and a desire to reclaim her family, broken apart by slavery.

Rachel’s character embodies the struggles of the formerly enslaved, not only in a quest for physical freedom but also in a search for emotional and familial healing. Her resolve is showcased through her persistence in finding her children despite the dangers and obstacles she encounters.

At the same time, Rachel undergoes a significant emotional transformation throughout the novel. She starts as a woman defined by loss and suffering, haunted by the memories of her stolen children.

However, as she reconnects with her surviving family, she learns that freedom is not just physical liberation but also the emotional ability to let go and accept the paths her children have taken. This acceptance is most profoundly illustrated in her relationship with Cherry Jane, where Rachel must come to terms with the fact that freedom means different things for different people.

Mary Grace

Mary Grace, Rachel’s eldest daughter, plays a crucial role in her mother’s quest. When Rachel first finds her in Bridgetown, she is working as a servant in a clothing shop.

Mary Grace’s character is gentle and supportive, often functioning as a silent strength for Rachel. Over time, her importance grows not only as a physical companion on their journey but as an emotional anchor for Rachel, particularly after Micah’s death.

Mary Grace’s voice, lost for years due to trauma, metaphorically symbolizes the silencing effects of slavery and its associated violence. By the novel’s end, when Mary Grace sings for the first time in years, her voice symbolizes a reclaiming of identity, freedom, and hope.

This act of singing becomes an embodiment of both personal and communal healing.

Nobody

Nobody is a complex and mysterious character who first meets Rachel on the ship to British Guiana. His name itself reflects his ambiguous status, one that defies typical categorization within the context of slavery and freedom.

Throughout the novel, Nobody is a figure of both strength and vulnerability. He acts as a protector, particularly to Rachel and Mary Grace, helping them in practical ways during their journey.

Nobody’s role expands beyond that of a mere helper, as he represents the community of displaced people whose identities were erased by slavery. His injury during the journey underscores his humanity, and his selfless actions show the power of solidarity and sacrifice.

By marrying Mary Grace, Nobody’s character arc symbolizes a kind of rebirth, both for him and for the fractured communities that slavery sought to destroy.

Thomas Augustus

Thomas Augustus is Rachel’s son who escaped from slavery and established himself in a liberation village. His character represents a different form of resistance, one rooted in the physical and psychological separation from the horrors of slavery.

Unlike Rachel, who searches for her children, Thomas is content with his self-liberation and the life he has built in the village. He is a man shaped by survival, but also by a deep sense of individual freedom that contrasts with Rachel’s focus on family.

His initial anger at Rachel’s decision to leave stems from his belief that freedom is best lived in the moment and in solitude, unburdened by the past. His eventual acceptance of Rachel’s decision shows his growth and his realization that freedom can take many forms.

Thomas’s connection to the land and the natural world further deepens his character, symbolizing a return to indigenous and African roots as a source of strength.

Cherry Jane

Cherry Jane, Rachel’s daughter who is passing as a member of a mixed-heritage family in Trinidad, presents one of the more complex perspectives on freedom. Unlike Rachel, who defines freedom through family and reunion, Cherry Jane embraces her ability to assimilate into a different social class as her form of liberation.

Cherry Jane’s coldness toward her mother reflects her internal struggle with identity. She is caught between the world she has constructed for herself and the familial past that threatens to unravel it.

Her character highlights the difficult choices that former slaves had to make in order to survive and the emotional costs of those choices. While Cherry Jane’s path causes pain for Rachel, the novel treats her decision with respect, recognizing that her form of freedom, even though it involves denial of her origins, is as valid as Rachel’s quest for reunion.

Mercy

Mercy, Rachel’s youngest daughter, appears late in the novel, heavily pregnant and living under the thumb of a sadistic overseer. Her character is marked by tragedy, having experienced immense suffering, including the death of her partner Cato.

Yet, like her mother, Mercy shows resilience and strength. She warns Rachel about the dangers of trying to escape, yet ultimately joins her mother’s plan.

Mercy’s pregnancy and the birth of her child, whom she names Micah in honor of her lost brother, represent renewal and the possibility of a future untainted by the horrors of the past. Her character symbolizes the generational struggle for freedom, as she carries with her both the scars of slavery and the hope for a new beginning.

Nuno

Nuno is an orphaned Akawaio boy who aids Rachel and her group on their journey along the Demerara River. His presence in the story adds another layer to the novel’s exploration of colonialism, as he represents the Indigenous people of the region who have also suffered under European colonization.

Nuno’s knowledge of the land and river becomes crucial for the group’s survival. His connection to his heritage is a quiet but powerful counterpoint to the displacement experienced by the enslaved characters.

Nuno’s character represents the possibility of reconnection with one’s roots. Through him, Rachel learns more about Mama B’s philosophy of The Connection Between All Things.

His decision to stay at the liberation village shows his desire to find a place of belonging.

Quamina

Quamina is an Akan fugitive from slavery who discovers Rachel and her group on their journey to find Thomas Augustus. His character represents the legacy of African resistance to slavery, specifically the Akan people’s history of rebellion.

Quamina’s song, which he breaks into upon hearing Rachel’s story, becomes a symbol of the shared African cultural heritage that survived despite the brutalities of slavery. He plays a crucial role in guiding Rachel to Thomas and helping her understand that liberation is not just about physical escape but also about spiritual and cultural survival.

Quamina’s character reinforces the theme of community as a source of strength and healing.

Mama B

Although Mama B appears briefly at the beginning of the novel, her influence is felt throughout Rachel’s journey. Mama B introduces Rachel to the idea of The Connection Between All Things, a philosophy that informs Rachel’s understanding of freedom and her role in the world.

Mama B’s wisdom, grounded in an Indigenous and spiritual worldview, helps Rachel navigate the physical and emotional trials she faces. Her teachings about interconnectedness resonate as Rachel reconnects with her children, helping her realize that even in separation, they are bound together by love and memory.

Mama B’s character represents the wisdom of the elders and the importance of ancestral knowledge in the fight for freedom.

Elvira and Joseph Armstrong

Elvira and Joseph Armstrong are the owners of the clothing shop in Bridgetown where Mary Grace works. They provide Rachel and Mary Grace with the means to continue their journey by giving them money to sail to British Guiana.

Their kindness and generosity offer a brief respite in Rachel’s journey. They serve as a contrast to the cruelty Rachel has experienced from other whites.

While their characters are not central to the narrative, they represent the possibility of empathy and kindness in a world dominated by the brutalities of slavery. Their treatment of Rachel and Mary Grace underscores the complexity of human relationships in the post-slavery world.

Themes

The Interplay Between Freedom and Captivity in the Post-Abolition World

One of the most intricate themes in River Sing Me Home is the nuanced and often paradoxical relationship between freedom and captivity in the post-abolition Caribbean. The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which theoretically marked the end of slavery, is immediately undermined by the implementation of the apprenticeship system, keeping individuals like Rachel in a state of liminal bondage.

This system, which rebrands enslaved people as apprentices, creates a shadow of freedom, a pseudo-liberation where the structures of oppression remain intact, complicating the characters’ search for true autonomy. Rachel’s physical journey to find her children mirrors a psychological journey where freedom is not a fixed state but a continuous process, constantly challenged by societal, economic, and personal limitations.

Rachel’s children, too, embody different shades of this complex freedom: Cherry Jane’s decision to pass as the daughter of a wealthy couple, for instance, signifies her path to liberation, though one that comes with the cost of alienation from her roots. Thomas Augustus, meanwhile, lives in a fugitive village, representing a collective attempt at freedom that is nonetheless fragile, constantly threatened by the colonial order.

Maternal Grief as an Act of Resistance

The theme of maternal grief in River Sing Me Home is not merely a reflection of Rachel’s personal loss but becomes an act of defiance against the brutal colonial regime that systematically separates families. Rachel’s anguish over her missing children is a reminder that slavery attempted to sever the most fundamental human ties.

By reclaiming her role as a mother, she subverts a system designed to dehumanize her, transforming grief into a vehicle for agency and reclamation. Her journey is not simply a search for her children, but also a reclaiming of her own identity as a mother—a role denied to her by slavery.

This reclamation operates on both a personal and collective level; through Rachel’s quest, the novel echoes the historical reality of countless enslaved women who were forcibly separated from their children. Her grief over Micah’s death, and later her acceptance of Cherry Jane’s chosen path, further deepens the novel’s exploration of how motherhood can be both a source of empowerment and an intimate struggle against the forces of colonialism.

The ultimate reunion with her grandson, named Micah in a symbolic gesture of remembrance, is a testament to how grief transforms into a generational legacy of resistance, defying the erasure that slavery attempted to impose.

The Connection Between All Things: Interpersonal and Spiritual Reconciliation

Throughout River Sing Me Home, there is a recurring theme of interconnectedness, embodied most explicitly in the teachings of Mama B, who introduces Rachel to “The Connection Between All Things.” This philosophy highlights the novel’s broader spiritual and metaphysical underpinnings, suggesting that personal liberation is inextricably linked to communal and environmental relationships.

Rachel’s journey is not solely an external quest for her children but an internal awakening to the web of connections that define existence. This spiritual framework allows her to reconcile with the multiple losses and traumas she encounters, viewing them not as isolated tragedies but as part of a larger, universal continuum.

The novel elevates this idea of interconnectedness beyond mere human relationships, extending it to the natural world, as seen in Rachel’s growing awareness of the river’s symbolic and literal role in her life. The Demerara River, which becomes a conduit for her connection to her son Thomas Augustus and later for their escape, is an embodiment of this theme.

It suggests that freedom is not an isolated achievement but flows through a larger, interconnected system of human, spiritual, and environmental forces.

Silence and Voice: The Language of Oppression and Liberation

One of the most powerful thematic elements in the novel is the exploration of silence and voice as tools of both oppression and liberation. Rachel’s experience is shaped by the ways in which her voice is suppressed, either through the silence imposed by the colonial system or by her own emotional trauma.

Her daughter Mary Grace, too, is rendered mute for much of the novel, symbolizing the broader silencing of enslaved people. The loss of voice represents not only a personal trauma but also the larger historical silencing of enslaved individuals’ narratives.

However, the act of regaining voice—whether through literal speech or the metaphoric act of reclaiming one’s story—becomes central to the characters’ emancipation. The climactic moment when Mary Grace finally sings, using her voice for the first time in years, is charged with symbolic significance.

It represents not only personal healing but also the collective reclamation of narrative agency. The song itself is a link to the cultural traditions embodied by Quamina, an Akan fugitive, whose music symbolizes the endurance of African heritage amidst the rupture of slavery.

This intricate weaving of silence, voice, and music throughout the novel demonstrates how the control of language and expression becomes a battleground for freedom, and how the act of storytelling itself is an act of resistance against the forces that seek to erase and silence.

The Legacy of Trauma and the Quest for Healing

River Sing Me Home intricately examines the legacy of trauma through its portrayal of a post-emancipation Caribbean world still haunted by the scars of slavery. Trauma is not confined to the past but manifests in the present lives of the characters, shaping their identities, relationships, and choices.

Rachel’s journey is not just a quest to reunite with her children, but also a journey of healing—an effort to reconcile the irreparable damage done to her family and her psyche. The novel depicts trauma as a cyclical, generational force that Rachel must confront, not only for herself but for her children and grandchildren.

Characters like Thomas Augustus, who have physically liberated themselves from slavery, still bear the emotional and psychological wounds of their pasts. The lingering effects of colonial violence are seen in the varied ways the characters respond to their trauma—some, like Cherry Jane, choose assimilation as a form of self-preservation, while others, like Thomas, seek refuge in isolation.

However, the novel suggests that healing cannot come from denial or avoidance; it requires confrontation and acknowledgment of the past. The birth of Mercy’s child, named Micah, symbolizes a fragile but hopeful continuity, a possibility that the next generation can transcend the traumas of their ancestors.

Ultimately, healing in River Sing Me Home is not depicted as a singular, definitive event but as an ongoing process that must be nurtured across time, space, and generations.