Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler Summary, Characters and Themes

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler is a piercing and intimately drawn portrait of a woman entangled in the emotional and psychological storm of obsessive love, familial estrangement, and creative identity. The novel follows Noa, a filmmaker drifting through personal and professional uncertainty, whose brief but potent encounter with Teddy, a charming and emotionally elusive biotech executive, initiates a descent into longing, vulnerability, and eventual self-reclamation.

Kessler crafts a narrative that unflinchingly examines power dynamics, romantic illusions, and the yearning to be seen—both as an artist and a woman—through prose that is raw, witty, and heartbreakingly precise. Rosenfeld is less a love story and more an autopsy of desire.

Summary

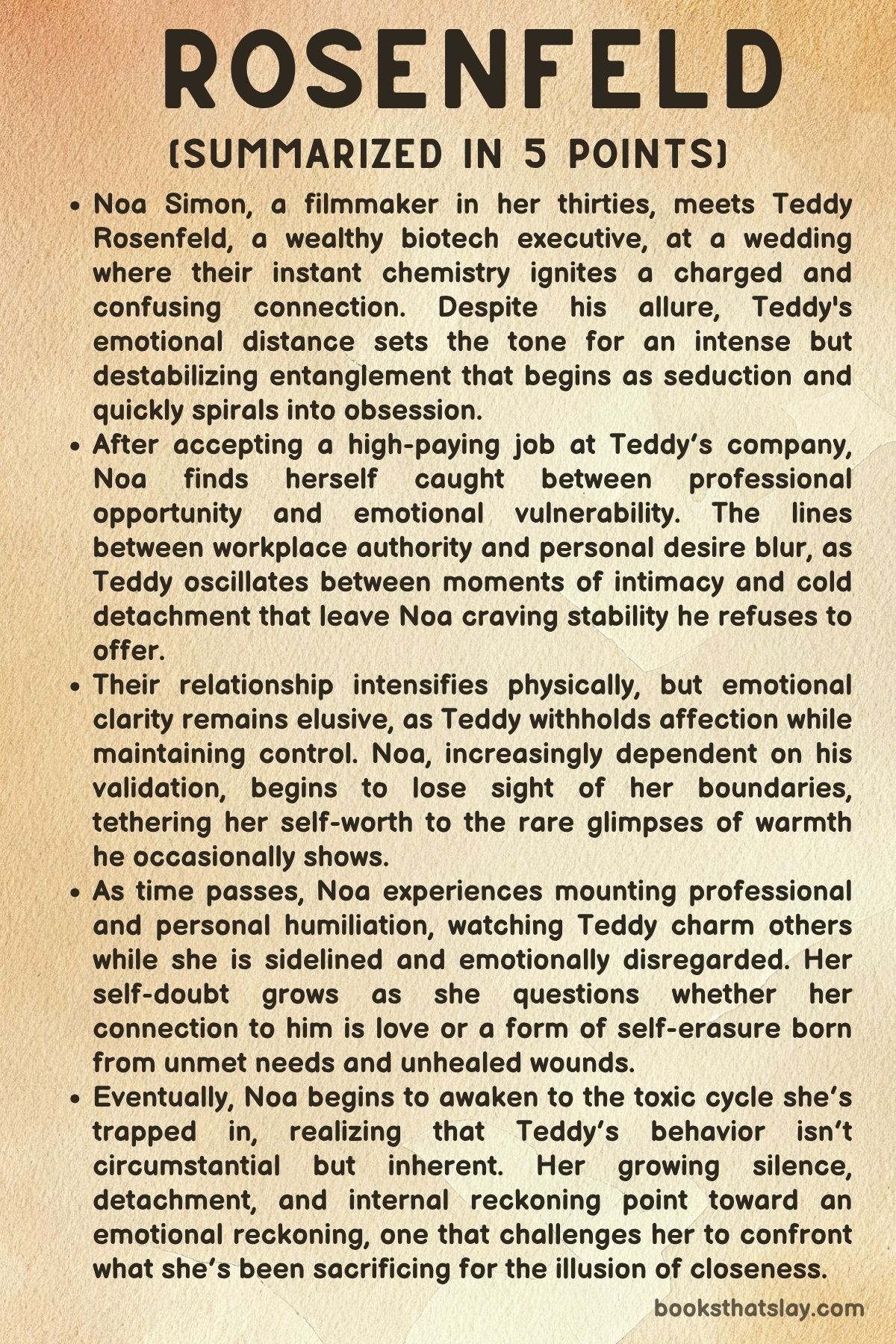

The novel opens with Noa meeting Teddy at a wedding, a moment charged with flirtation and ambiguity that sets the tone for everything that follows. Noa, a disillusioned filmmaker stuck in a professional rut, is immediately drawn to Teddy’s confidence and enigmatic charm.

Their banter is electric, their chemistry undeniable, and what begins as a playful exchange quickly becomes an emotionally charged and obsessive connection. Teddy is paradoxical—he warns Noa not to join his company, yet he later recruits her at double her expected salary.

This initial contradiction becomes emblematic of their entire relationship: an emotional game built on proximity without intimacy, signals without commitment.

As Noa starts working at Teddy’s company, her personal and professional identities begin to blur. She becomes consumed by her interactions with him, interpreting every comment, every silence, every glance through the lens of longing.

Her internal world, narrated with biting clarity and self-awareness, is a swirl of hope, doubt, and emotional instability. Her attraction to Teddy becomes a full-blown obsession.

Her creative ambitions begin to erode, her daily routine distorts around the possibility of encountering him, and her past relationships and family connections seem dull by comparison.

Teddy remains emotionally elusive. He oscillates between warmth and detachment, inviting Noa into his life only to push her out again.

Their dynamic is marked by late-night emails, charged conversations, and erratic encounters. Each time they get close—emotionally or physically—he retreats.

Noa, desperate for clarity, often ends up humiliated, her desire laid bare against Teddy’s measured restraint. Her emotional investment only deepens despite this imbalance, and she begins to question her worth and sanity in the face of his cool indifference.

Their sexual encounters, while intense and passionate, only heighten the sense of imbalance. They are vivid, cinematic, and emotionally loaded, often leaving Noa more vulnerable than satisfied.

She clings to these moments as proof of a deeper connection, but Teddy’s subsequent withdrawal always reestablishes the emotional distance. At one point, when he disappears without explanation, Noa is devastated, her sense of self-worth shattered.

The power dynamic between them becomes more pronounced: he is in control, and she is left waiting, hoping.

The emotional toll begins to impact Noa’s work. Her film project at the company is initially met with enthusiasm but is later undermined.

Teddy fails to advocate for her when it matters most, highlighting the limits of his support. A particularly painful moment occurs in an elevator when Teddy chastises her in front of others, igniting a spiral of shame and self-doubt.

Professionally and personally, Noa is destabilized.

Despite moments of clarity—when she recognizes her own destructive behavior, such as sending a drunken email or seeking attention in unhealthy ways—Noa cannot let go. A second sexual encounter with Teddy is even more chaotic and intense, revealing the depth of their dysfunction.

They share moments of honesty, drug-fueled laughter, and confessions about past relationships, but these are fleeting. Teddy continues to keep her at arm’s length, reinforcing his emotional boundaries even as he draws her in physically.

Parallel to this romantic turmoil is Noa’s complicated family history. Her relationship with her grandmother offers brief moments of warmth and grounding, while her estranged relationship with her mother, Nurit, adds emotional weight.

When Noa agrees to meet Nurit after years of silence, the encounter is fraught with tension and nostalgia. They reconnect through shared memories and a fragile emotional detente, revealing the depth of Noa’s longing not just for romantic connection but for familial reconciliation.

Another subplot that deepens the emotional stakes is the revelation of Teddy’s involvement with Lara, the former lover of his own son, Adrian. This disclosure devastates both Adrian and Noa, casting Teddy in a morally compromised light and revealing the extent of his emotional recklessness.

Noa learns of this betrayal in a raw nighttime conversation with Adrian, who confides his deep hurt and disillusionment. This confrontation further destabilizes her perception of Teddy and forces her to question the entire foundation of their relationship.

As her professional life begins to show signs of revival—she is offered a chance to direct a television comedy with Greg, a colleague and former childhood acquaintance—Noa starts to regain some measure of agency. Her creative contributions are recognized, and her collaboration with Greg feels authentic and invigorating, contrasting sharply with the emotional disarray of her connection to Teddy.

Yet, even with this opportunity, she remains emotionally entangled with him.

The emotional climax comes when Noa and Teddy have a final conversation after he reads her manuscript. There is mutual acknowledgment of her talent and a bittersweet recognition of their incompatible desires.

They share one last moment—intimate, charged, but marked by the understanding that they cannot continue as they are. It is a goodbye filled with sorrow, not drama.

The novel ends on a note of tentative resolution. Noa begins to reclaim her life, sending out job applications, cleaning her neglected apartment, and spending time with her grandmother and Nurit.

She reflects on her journey and recognizes the illusions she built around Teddy. Though the ache remains, there is a shift.

She has not won him, nor has she completely healed, but she has begun to see the truth of her experience and take steps toward autonomy.

Rosenfeld is ultimately a portrait of a woman waking up from the dream of another person. It captures the emotional chaos of being consumed by love and the painful clarity that follows.

Through Noa’s journey, Kessler gives voice to the contradictions of longing—how it can be both illuminating and erasing—and how reclaiming oneself often begins with heartbreak.

Characters

Noa

Noa is the gravitational center of Rosenfeld, a woman whose inner life is as turbulent and vibrant as her external world is constrained and undefined. A filmmaker by trade but emotionally adrift, Noa is caught in the constant friction between her creative desires, romantic yearnings, and need for personal stability.

From the very start, Noa’s character is shaped by her acute sensitivity and obsessive temperament. She imbues each moment with emotional intensity, often to her own detriment, especially in her interactions with Teddy.

Her infatuation with him becomes the axis upon which her emotional world spins, coloring her perceptions of work, family, and self-worth. She oscillates between moments of self-aware humor and despairing vulnerability, desperately seeking affirmation but always sensing its elusiveness.

Noa’s psyche is also marked by an intrinsic conflict—she wants to be seen and cherished, but she fears humiliation and invisibility, leading her to sometimes perform emotionally self-destructive acts for fleeting intimacy or attention.

Her family relationships further underline her search for meaning. The reunion with her estranged mother, Nurit, is both painful and redemptive, serving as a narrative mirror to her emotional development.

Noa’s interactions with her grandmother and her sensitivity to generational trauma reflect the roots of her insecurities and craving for connection. Professionally, her experiences are no less fraught.

She’s talented and passionate, but easily undermined, particularly when her work is dismissed or compromised in the emotionally charged environment of Teddy’s company. Her growth is hard-earned.

By the end of the narrative, Noa begins to reassert agency, not with grand gestures, but in subtle ways—cleaning her apartment, reconnecting with her creative goals, and distancing herself from Teddy’s manipulative gravitational pull. Her evolution is about regaining control over her narrative, not just as an artist but as a woman reclaiming her emotional sovereignty.

Teddy

Teddy is a charismatic yet emotionally elusive figure, a man whose allure lies in his contradictions. In Rosenfeld, he is both the catalyst for Noa’s self-destruction and the object of her desire.

As a biotech executive with a commanding presence, Teddy exerts influence not just in boardrooms but in every room he enters. He is seductive not merely through physicality, but through ambiguity—offering warmth and affection in fleeting moments before pulling back into cold detachment.

His emotional inaccessibility is both intentional and habitual. Teddy seems addicted to control, carefully orchestrating how much of himself he reveals, constantly shifting the goalposts of intimacy.

He flirts with vulnerability—talking about his sons, past relationships, and regrets—but only to the extent that it maintains his dominance in emotional power dynamics.

Teddy’s relationships are transactional and layered with discomfort. His romantic past is murky and ethically troubling, especially the revelation that he fathered a child with Lara, a woman previously involved with his own son, Adrian.

This shocking detail underscores Teddy’s tendency to collapse boundaries in pursuit of his desires, regardless of the emotional consequences for others. He embodies the paradox of nurturing cruelty—offering Noa professional opportunities, material comforts, even moments of tenderness, while simultaneously invalidating her work and emotions.

His betrayal in Michigan, where he dismisses Noa’s creative contribution over a petty grudge, reveals his incapacity for emotional generosity. Teddy is not heartless, but he is self-serving, locked in a cycle of drawing people close just to keep them dangling at arm’s length.

His final interactions with Noa are tinged with regret and confusion, but by then, the emotional damage is already done.

Nurit

Nurit, Noa’s mother, is a quieter yet profound presence in Rosenfeld, embodying both emotional absence and the possibility of reconciliation. Their estranged relationship is painted in strokes of unresolved tension and tentative hope.

Initially introduced through Noa’s anxiety and resentment, Nurit emerges as a deeply flawed but remorseful figure. Her reunion with Noa is hesitant, marked by formality and emotional landmines.

Yet beneath her awkwardness is a longing for connection, a desire to bridge the chasm that time and silence have carved. Nurit is overwhelmed by her daughter’s guardedness but respects it, attempting to rebuild trust through small acts of intimacy—sharing weed, revisiting childhood memories, and simply being present.

Nurit’s role is crucial in illuminating Noa’s deeper emotional currents. Their interaction reveals a lineage of emotional distance, inherited silence, and unresolved grief.

In rekindling this bond, Noa begins to untangle some of the roots of her own craving for love and validation. The mother-daughter dynamic is not wrapped up neatly, but it opens a space for healing.

Nurit becomes a symbol of generational reckoning, showing that it’s never too late to begin repairing damage, even if some scars remain permanent.

Adrian

Adrian, Teddy’s son, serves as a poignant contrast to his father’s manipulative charm. He is vulnerable, emotionally transparent, and deeply wounded by his father’s betrayal.

His brief but powerful presence in Rosenfeld provides moral clarity in a story riddled with emotional murkiness. The night-time confrontation with Noa, in which Adrian reveals Teddy’s relationship with Lara, is a moment of raw honesty and shared grief.

His hurt is not just about romantic betrayal, but about the collapse of paternal trust. Adrian helps ground Noa’s perception of Teddy, offering an unfiltered perspective on the emotional cost of Teddy’s actions.

Adrian also embodies an emotional vulnerability that Noa recognizes in herself. Their brief connection is less about romance and more about witnessing each other’s pain.

Adrian doesn’t seek control or validation; he seeks understanding, and in doing so, offers a form of emotional clarity that Noa has not found elsewhere in the story. He is a reminder that suffering can be dignified, and that truth, even when painful, can be a pathway to freedom.

Frank

Frank is a gentler presence in Noa’s life, representing an emotional haven that is free from the volatility of her relationship with Teddy. Categorized in Noa’s mind as a “cousin” type—familiar, safe, reliable—Frank nevertheless offers her something profound: genuine emotional reciprocity.

Their night together is a moment of unexpected solace, filled with quiet affirmation rather than desperate passion. Frank listens, supports, and sees Noa in a way Teddy never does.

Yet this comfort is bittersweet. Noa, conditioned to equate passion with pain, cannot fully embrace the steadiness Frank offers.

His kindness, though sincere, lacks the chaos she has come to associate with romantic intensity.

Despite this, Frank serves an important function in the narrative. He embodies the possibility of a different kind of love—one rooted in mutual respect and emotional availability.

While Noa may not choose Frank romantically, her encounter with him subtly shifts her understanding of what she deserves. He is a counterpoint to Teddy’s destructiveness, proof that not all intimacy must come at the cost of dignity or emotional survival.

Lara

Lara is a peripheral but pivotal character in Rosenfeld, acting as a silent disruptor of both Noa and Adrian’s emotional worlds. Her involvement with Teddy—and the fact that she bore his child—exposes the depth of Teddy’s moral failings.

Though she is never deeply fleshed out, Lara’s presence looms large, casting shadows over every relationship touched by Teddy’s desire. To Adrian, she represents betrayal.

To Noa, she is both a rival and a mirror, another woman drawn into Teddy’s web and left to navigate the emotional wreckage. Lara’s suffering, though often implied rather than shown, deepens the emotional complexity of the story, reinforcing themes of abandonment, female complicity, and the cost of male entitlement.

Greg

Greg, a TV show creator and childhood acquaintance of Noa’s, emerges late in the narrative as a symbol of professional renewal and creative validation. Unlike the emotionally fraught dynamics that dominate much of Rosenfeld, Greg’s presence is refreshingly uncomplicated.

He sees Noa’s talent, respects her voice, and offers her the creative freedom she’s been craving. Their reconnection is serendipitous, but it also marks a narrative pivot—one where Noa begins to reclaim her sense of self not through love or validation, but through work and artistic contribution.

Greg’s easy collaboration and appreciation of Noa’s pitch contrast starkly with Teddy’s manipulations, suggesting that perhaps growth lies not in intensity, but in recognition and mutual respect.

Themes

Obsession and Emotional Displacement

Noa’s infatuation with Teddy consumes her internal and external world, replacing professional ambition and personal clarity with constant emotional volatility. Her desire for Teddy morphs into obsession, where every gesture or silence from him is analyzed for hidden meaning.

The imbalance between her yearning and his aloofness pushes her to neglect her own boundaries, identity, and needs. This obsessive longing is not just romantic but existential—Noa begins to attach her self-worth to Teddy’s inconsistent attentions.

Her apartment becomes a metaphor for her deteriorating inner state: neglected, cluttered, and chaotic. The space that once held creative energy becomes a backdrop to despair, as she waits for his validation.

Even when she secures a job or professional milestone, it’s refracted through the lens of her attachment to him. The boundaries between emotional desire and professional ambition dissolve, and she finds herself sacrificing creative autonomy for fleeting moments of emotional proximity.

This theme captures the brutal irony of wanting something so badly that it dismantles the very foundation of who you are.

Power, Control, and Asymmetry in Relationships

The dynamic between Noa and Teddy operates on a persistent imbalance of emotional power. Teddy’s approach is to grant glimpses of vulnerability, followed by sharp withdrawals, keeping Noa perpetually off-balance and craving more.

His contradictory behaviors—hiring her after warning her not to work for him, offering kindness followed by detachment—create a psychological loop in which Noa becomes increasingly invested despite the absence of emotional reciprocity. The more she seeks clarity, the more he obscures his intentions.

Power is not just expressed through professional hierarchy but also through emotional manipulation. Teddy’s cool reserve and ability to dictate the terms of their relationship underscore his control.

Noa, meanwhile, is stuck in a reactive position, attempting to decode signals, justify his silence, or repair perceived damage. Even their sexual encounters are imbued with themes of surrender and dominance, reinforcing the imbalance.

The push and pull is not only painful but corrosive, exposing how emotional dependence often masquerades as passion when in truth it is rooted in a skewed dynamic of control.

Artistic Identity and Creative Erosion

Noa’s background as a filmmaker and creative thinker is introduced as a central part of her identity, yet throughout the narrative, her creative self is slowly pushed aside. What begins as a promising project tied to her talents becomes diluted by office politics, gender dynamics, and her own emotional entanglement with Teddy.

When her pitch film is dismissed without proper acknowledgment, it reflects a broader narrative about how women’s creative contributions are often sidelined in male-dominated spaces. This dismissal isn’t merely professional—it wounds her on a personal level, feeding into her growing sense of invisibility and helplessness.

Her creative decline is paralleled with her increasing fixation on Teddy, suggesting that emotional dependence can drain the vitality necessary for artistic expression. Her final return to her apartment and decision to clean, reflect, and send out job applications symbolizes a faint but real reclamation of her creative agency.

The theme highlights how creativity can become a casualty in emotionally manipulative relationships, especially when the validation of one’s art is entwined with the affections of an emotionally withholding partner.

Maternal Estrangement and Intergenerational Healing

Noa’s strained relationship with her mother, Nurit, adds a layer of emotional depth to her psychological portrait. Their reunion is laden with hesitation and guardedness, but also flickers of tenderness and shared history.

Unlike the unresolved nature of her romantic entanglements, this familial thread moves toward cautious reconciliation. Weed, memory-sharing, and subtle physical gestures become tools for navigating old wounds.

Their relationship shows that while romantic love may fracture without resolution, familial bonds, though damaged, can still be repaired. The intergenerational trauma and silence that define their dynamic mirror Noa’s inability to express her needs with Teddy.

Yet unlike with Teddy, Noa and Nurit inch toward honesty and vulnerability, revealing that healing requires mutual effort, not emotional withholding. This theme shows how unresolved childhood experiences with parents can unconsciously shape adult relationships and emotional responses.

Noa’s willingness to meet her mother halfway signals her potential for growth and self-understanding, making it one of the few arcs in the story that leans toward hopeful change.

Emotional Masochism and Self-Erosion

Noa’s self-awareness never fully shields her from emotional self-sabotage. She often recognizes her behavior—her obsessive emails, self-deprecating inner thoughts, neediness—but is unable to stop.

This disconnect reveals a deeper pattern of emotional masochism, where she seems to seek out situations that confirm her deepest fears of being unlovable or unworthy. Her relationship with Teddy is the crucible through which this self-erasure is enacted.

She allows herself to be demeaned, overlooked, and emotionally discarded, yet remains tethered to the hope that he might one day reciprocate her intensity. Her emotional barometer is dictated by his reactions, and she often tolerates humiliation in exchange for fleeting affection.

Even her sexual behavior at times mimics submission or degradation, as if attempting to earn attention through self-effacement. These actions are not framed as empowerment but as coping mechanisms for deeper emotional voids.

In this light, emotional masochism is not just about loving the wrong person but about not knowing how to love oneself without external validation. The narrative reveals how self-erasure can masquerade as devotion and how breaking this cycle is the true path to healing.

Ambiguity, Incompleteness, and the Search for Closure

Throughout Rosenfeld, emotional and narrative closure is repeatedly deferred, leaving characters—especially Noa—caught in limbo. Conversations stop short, relationships end ambiguously, and truths are only partially revealed.

This constant lack of resolution fuels Noa’s anxiety and longing. Teddy’s behavior embodies this theme: he never fully explains his absences, never articulates his intentions, and rarely provides clear emotional signals.

Their final encounter—tender, erotic, and ultimately empty—serves as a symbolic full stop to this pattern. Noa wants understanding, perhaps even accountability, but gets silence.

The ambiguity extends to her career as well, where successes are quickly followed by professional undermining. This incomplete closure becomes a psychological motif, showing how people often cling to the hope of resolution in order to justify ongoing emotional investment.

Yet by the end, Noa begins to understand that closure may never arrive in a neat form. Her journey is less about receiving clarity from others and more about creating internal acceptance.

This theme underscores the emotional reality that some chapters end not with answers but with the decision to walk away despite not having them.