Saga Volume 11 Summary, Characters and Themes

Saga Volume 11 is obviously the 11th installment in Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ long-running sci-fi/fantasy comic series, Saga.

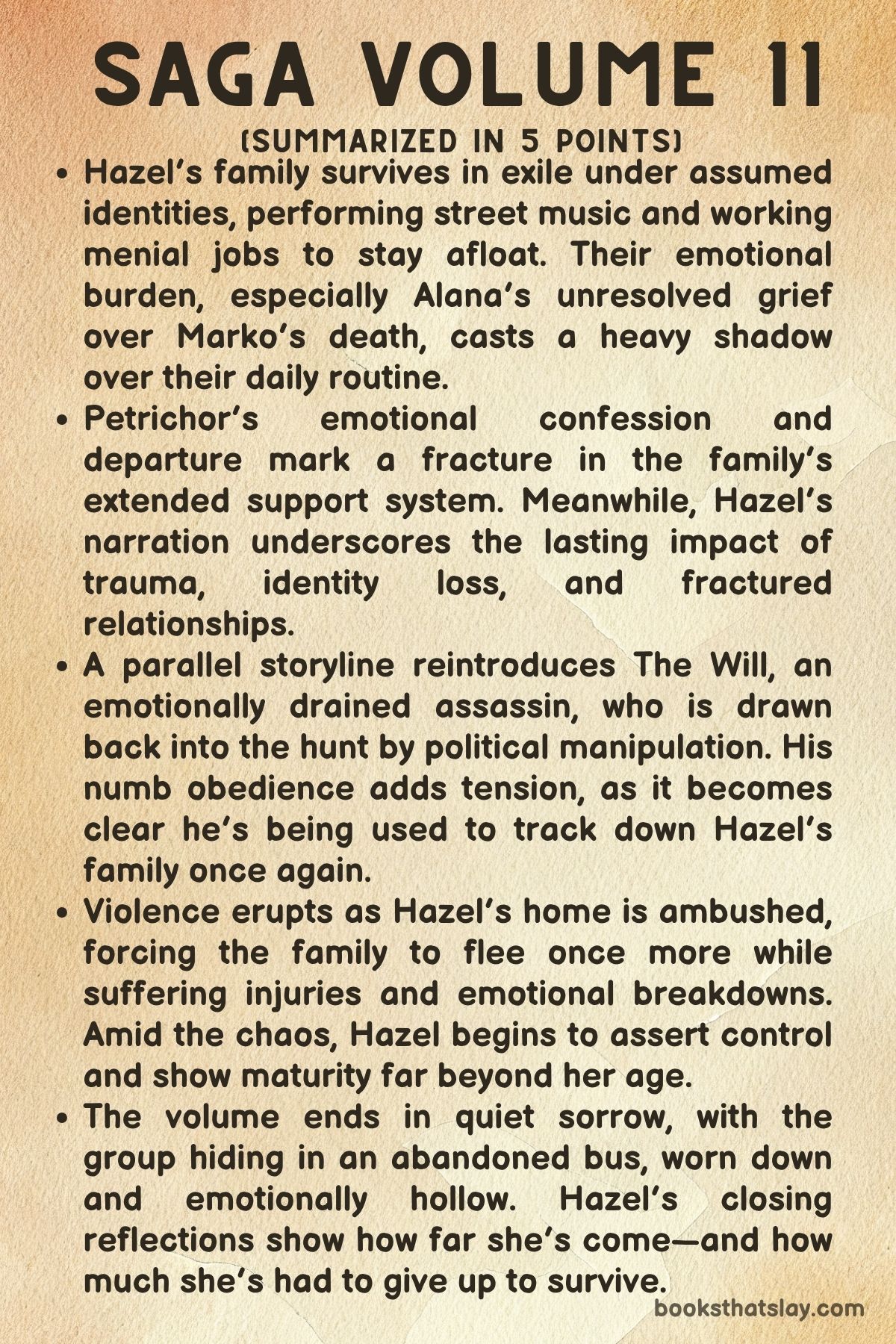

Known for blending sweeping intergalactic conflict with deeply human family drama, this volume resumes the journey of Hazel and her mother Alana as they navigate life on the run after the traumatic loss of Marko, Hazel’s father. The volume shifts between moments of fragile intimacy and explosive violence. It constantly examines themes of grief, identity, political manipulation, and survival.

While fantastical in setting, the story remains grounded in its portrayal of relationships, loss, and the psychological toll of endless war.

Summary

Volume 11 opens in a dark, emotionally charged setting, with Alana haunted by a dream of Marko proposing to her. What begins as a tender memory quickly morphs into a nightmare, reflecting the unresolved grief she carries.

Waking from this hallucination, Alana finds herself in a makeshift shelter, part of a displaced community struggling to survive under false identities. Hazel, now older and wiser, narrates from a place of quiet maturity.

She and her little brother earn coins performing music on the streets with their robotic friend, Squire. Alana works a physically draining job, and their fragile routine underscores their fall from stability and the day-to-day anxiety of being fugitives in a hostile galaxy.

Hazel reflects on the death of her father and the fruitless attempts to bring his killer to justice. These memories resurface as Alana and their old ally Petrichor grapple with guilt, trauma, and diverging visions for the future.

A rift opens when Petrichor confesses her love for Alana and is rejected. This adds another emotional fracture to their already strained dynamic.

Elsewhere, a seemingly unrelated family is attacked when Ginny—another figure linked to Alana’s past—is ambushed by a government agent. The violence that follows is sudden and brutal, putting Ginny’s entire family at risk.

Hazel and her companions remain trapped in the routine of hiding and fleeing. Squire, still a child despite his robotic frame, is deeply shaken after a moment of unintended violence.

He isolates himself, struggling with guilt. Alana, burdened by fear and responsibility, becomes increasingly controlling, creating further tension with Hazel.

Through it all, Hazel’s narration reflects a growing detachment. She is no longer a child shaped by innocence, but by necessity and survival.

The narrative also follows the return of The Will, a former assassin manipulated into action by Agent Gale. Depressed and emotionally hollow, The Will is coerced into hunting Hazel’s family again under the pretense of restoring justice.

This subplot develops in chilling parallel, as The Will begins executing targets with cold efficiency. His emotional numbness mirrors Hazel’s increasing internal withdrawal.

Back in Hazel’s world, a sudden attack shatters their temporary peace. A masked assailant storms their shelter, initiating chaos and destruction.

Alana, unarmed but desperate, throws herself into combat to protect her children. Hazel responds with courage and quick thinking, while Squire freezes, overwhelmed by the violence.

Their once-safe space is reduced to rubble. They are forced to flee yet again with few belongings and many injuries.

The cost of survival keeps compounding. The trauma accumulates with each new escape.

The final chapter shifts to a slower pace as the survivors regroup in an abandoned bus in the forest. Alana, wounded but unrelenting, tries to remain strong for her children.

Hazel steps into a new emotional role—not only as narrator but as a quiet leader within the family. Her thoughts betray a deepening cynicism.

She sees emotions as liabilities. She begins to view her own grief as something permanent.

As The Will continues his killing spree in silent, mechanical fashion, Hazel comes to see her family not as heroic survivors, but as forgotten ghosts. Her worldview darkens, shaped by endless danger and emotional fatigue.

The volume closes with Hazel alone, watching over her family as they sleep. Her childhood has given way to vigilance, her innocence replaced by responsibility.

There is no resolution, no safety. Only the quiet knowledge that they are still running, and the world has not yet stopped coming for them.

Characters

Hazel

Hazel emerges in Saga Volume 11 as a deeply reflective and emotionally complex narrator. Her childhood has been shaped by relentless war, displacement, and grief.

No longer the passive child of earlier volumes, Hazel is now a young adolescent forced to mature rapidly. This change is due to the constant dangers surrounding her.

Her narration evolves into a mechanism of both observation and emotional self-protection. She recounts the traumatic murder of her father, Marko, while processing the chaos that follows.

Hazel becomes increasingly self-reliant and emotionally guarded. Her identity crisis as a child born of two warring races lingers in her inner monologue.

She learns to navigate a world where visibility can mean death. Despite her age, she displays remarkable composure in moments of crisis, especially during the violent raid in Chapter Sixty-Five.

Yet, the cost of this maturity is clear. Hazel often suppresses her feelings, speaks of safety as a forgotten concept, and considers emotional detachment a necessary tool for survival.

Her relationship with her mother, Alana, is increasingly strained. She seeks autonomy in a life marked by instability and fear.

Through Hazel, the narrative weaves themes of lost innocence, generational trauma, and the painful evolution of identity under fire.

Alana

Alana’s journey in Saga Volume 11 is one of endurance through trauma, grief, and maternal desperation. She is depicted as a woman carrying the impossible burden of protecting her family.

Following the death of her partner Marko, her waking life is marked by exhaustion, low-wage work, and constant vigilance. Her parenting becomes an uneasy mixture of fierce love and suffocating control.

Alana’s mental health is explored in surreal ways, such as a traumatic dream of Marko turning hostile. This illustrates her unresolved grief and guilt.

She attempts to fill the void left by Marko with a new partner. But the relationship feels more like a coping mechanism than genuine solace.

Her role is not only maternal but symbolic of resilience in the face of emotional and societal collapse. She physically defends her children during the home invasion, enduring a gunshot wound while refusing to falter.

Alana’s body and soul bear the marks of sacrifice. Her unwavering will to protect Hazel and the rest of the family cements her as one of the saga’s emotional anchors.

Squire

Squire, the robotic child companion, undergoes a subtle but harrowing transformation throughout Saga Volume 11. He represents the psychological damage inflicted on children raised in war zones.

Once a symbol of innocence and quiet curiosity, he now embodies trauma, silence, and a growing emotional paralysis. In an early chapter, he accidentally causes harm and is overwhelmed with guilt.

From then on, Squire becomes increasingly withdrawn. He no longer engages in play or conversation.

He freezes in moments of danger, particularly during the home invasion. Hazel’s attempts to reach him emotionally are met with resistance.

His robotic nature makes his emotional expressions ambiguous. Yet the narrative uses his silence and reactions to portray a child trying—and often failing—to process trauma.

Squire’s presence adds emotional texture to the family dynamic. He reflects the quiet suffering that often goes unnoticed in children affected by conflict.

The Will

The Will returns in Saga Volume 11 as a ghost of his former self. He is now a shell of merciless efficiency.

Once a bounty hunter with moments of reluctant compassion, he has become an emotionless weapon. Political forces now manipulate him with ease.

His grief over past losses has metastasized into numb compliance. Agent Gale exploits this, reactivating him as a tool of destruction.

The Will no longer debates morality. He kills silently, with mechanical precision.

His physical disrepair mirrors his internal disintegration. The man who once showed glimmers of humanity has been eroded by loss and isolation.

He now serves as a cautionary figure. The Will shows what happens when vengeance and grief are all that remain.

He functions as a dark mirror to Hazel. He represents the path she might walk if she fully embraces emotional desensitization.

Petrichor

Petrichor’s appearance in Saga Volume 11 is emotionally significant. She deepens the themes of love, loss, and unreciprocated connection.

A battle-hardened survivor, Petrichor reveals her vulnerability when she confesses her love for Alana. The moment is met with quiet rejection.

This confession is not just romantic. It is also an emotional outpouring born from shared trauma and a yearning for connection.

Alana rebuffs her, and Petrichor accepts the loss with stoic sorrow. Her departure symbolizes yet another fracture in an already fragile family.

Petrichor’s character highlights the difficulty of forming authentic emotional bonds. In a world where intimacy is both dangerous and fleeting, she walks away carrying silent grief.

Her exit marks the end of a chapter. It closes the door on a potential emotional anchor for Alana.

Ginny

Ginny’s arc in Saga Volume 11 is tragically brief. Yet it plays a crucial role in illustrating the indiscriminate reach of violence.

Her life, once separate from Hazel’s chaos, is violently upended. A government agent invades her home, threatening her family.

Ginny reacts with ferocity, defending her loved ones. Her resistance reveals strength and maternal instinct.

Despite her bravery, the attack leaves her gravely injured. The panel ambiguity suggests that she and her partner may not survive.

Ginny’s story shows that even those on the periphery are not safe. War finds everyone eventually.

Through Ginny, the narrative illustrates how peace can shatter in an instant. Bravery does not guarantee survival in this world.

Agent Gale

Agent Gale is the embodiment of bureaucratic malevolence in Saga Volume 11. He represents systemic power and quiet corruption.

As a political manipulator, he avoids direct violence. Instead, he causes immense damage by directing others like The Will to commit atrocities.

Gale operates with charm that masks cold calculation. He knows exactly how to exploit emotional fractures for his own goals.

His ability to weaponize grief makes him a chilling figure. He reactivates The Will through psychological manipulation, not coercion.

Gale doesn’t kill with his own hands. But he engineers death through influence and rhetoric.

He is always several steps removed from the suffering he causes. This detachment makes his presence all the more insidious.

Themes

Grief and Emotional Survival

One of the themes in Saga Volume 11 is the ongoing grief experienced by the central characters, especially Alana and Hazel, as they cope with the death of Marko. This grief is not a singular moment but an evolving condition that shapes their every action, conversation, and decision.

Alana’s waking moments are haunted by hallucinatory nightmares and emotional numbness, often depicted through jarring transitions between dreams and reality. Her interactions, whether in the form of sarcastic deflection or intense maternal protection, are saturated with the pain of unresolved loss.

Hazel, as both character and narrator, begins to process grief not just as the absence of her father, but as a force that redefines her identity and worldview. The emotional burden has hardened her, aging her emotionally beyond her years.

For both Alana and Hazel, grief is not static but a mutating force. It shapes their interactions, pushes away companions like Petrichor, and leaves them feeling emotionally exiled.

The grief is also mirrored in secondary characters like Squire and The Will. Their silent suffering and emotional detachment underscore how personal loss reverberates across physical and moral boundaries.

This theme builds across the volume. It concludes in a quiet emotional paralysis in Chapter Sixty-Six, where Hazel declares that feelings are luxuries she can no longer afford, signaling a bleak but necessary internal shift toward emotional survivalism.

The Erosion of Childhood and Innocence

Hazel’s narrative across the volume reveals a slow erosion of innocence, replaced with maturity that is both earned and tragic. From the outset, she is depicted as a child forced into roles beyond her years—street performer, caretaker, observer of adult failings.

Her narration carries a reflective, at times poetic detachment, as if she is observing her life through the lens of someone older and emotionally distanced. The environment around her—marked by hiding, hunger, violence, and sudden death—necessitates a kind of emotional numbing.

Childhood for Hazel and Squire is no longer a period of growth and imagination, but one of survival and performance. Squire’s character arc in particular dramatizes this loss.

His accidental violence and subsequent withdrawal signify the trauma of a child who realizes he can inflict harm. There is no space for comfort or recovery; instead, there is only motion, escape, and preparation for the next danger.

Even play and humor are tinged with melancholy. Hazel’s eventual acceptance of silence and concealment as survival tools illustrates that her childhood has been replaced by an armor of psychological withdrawal.

By the end of the volume, Hazel equates herself not with the living, but with the forgotten. This marks a symbolic death of childhood and the rise of a hardened, pragmatic youth shaped by relentless crisis.

Family, Love, and Fractured Relationships

Family continues to be a central force in Saga, but in Volume 11 it takes on new dimensions defined by fragmentation and resilience. The core family unit—Alana, Hazel, and her baby brother—survives through constant movement, changing identities, and shared labor.

Yet the emotional bonds within this unit are frayed by loss, guilt, and exhaustion. Alana’s relationship with Hazel grows increasingly strained, as her attempts at control clash with Hazel’s burgeoning need for independence.

Their communication is often indirect, layered with subtext and stifled emotion. Meanwhile, romantic connections, such as Alana’s relationship with her new lover and Petrichor’s unrequited feelings, are shown as fleeting or corrosive, unable to offer the sanctuary they once promised.

Petrichor’s departure is particularly telling. Even when love is offered earnestly, the trauma of the past ensures it cannot be sustained.

On the other side of the spectrum, Hazel’s bond with her baby brother remains pure and tender. It is one of the few sources of light in an otherwise dim world.

Even amid violence, she nurtures and protects him. She clings to that connection as a way to retain some sense of purpose.

The volume ultimately presents family not as a fixed structure, but as a set of constantly evolving responsibilities and emotional negotiations. These are made even more fragile by the pressures of war, survival, and grief.

Violence, Fear, and the Collapse of Safe Spaces

Violence is a looming, ever-present threat throughout Volume 11, stripping the characters of any lasting sense of safety or stability. The settings—cave shelters, public streets, hideouts—are all temporary refuges that are eventually compromised.

Even domestic moments are pierced by sudden, brutal invasions, such as the masked attack in Chapter Sixty-Five that forces the family to flee yet again. These invasions are not merely physical but also psychological, eroding the characters’ belief that peace or stability is achievable.

The volume suggests that violence is not an aberration but a rhythm of existence in their universe. The Will’s return to form as a cold, efficient killer reinforces this idea.

His emotionless assassinations demonstrate how normalized killing has become, especially for those who’ve lost any emotional anchor. Hazel’s narration reinforces this grim reality, acknowledging that safety is an illusion and that home can only be found in transient, shared survival.

The visual metaphors—cracked vases, extinguished candles, dark forests—underscore how every haven is ultimately penetrable. In this universe, violence is not just a backdrop but a catalyst that reshapes relationships, motives, and self-perception.

The result is a chilling worldview where escape and defense are not strategies but conditions of life itself.

Identity, Secrecy, and Psychological Armor

The characters in Saga Volume 11 navigate a world that demands constant reinvention and concealment. For Hazel, identity becomes a malleable construct, something she must continuously adapt in order to survive.

Her mixed heritage, once a symbol of hope and unity, is now a liability that necessitates secrecy. This necessity extends beyond names and locations to psychological states; Hazel learns to hide her feelings, thoughts, and even memories.

She begins to treat vulnerability as dangerous and introspection as a threat to survival. This process of internal concealment is mirrored in Squire, whose trauma pushes him into emotional silence.

The symbolism of masks—both literal and metaphorical—runs through the volume, representing the characters’ need to suppress parts of themselves in order to function. Alana too performs emotional labor, hiding her suffering behind sarcasm and maternal duty.

The Will represents the endpoint of this identity erasure, functioning as a weapon stripped of personal desire or ethical compass. Across the board, identity becomes not a celebration of self but a risk factor to be managed.

By the end, Hazel imagines herself wearing a mask made of grief. This signals that what once were survival strategies have now become intrinsic aspects of her personality.In this way, Saga Volume 11 constructs a chilling commentary on how secrecy and emotional suppression, though initially protective, can ultimately reshape the self into something colder, harder, and less whole.