Saltwater by Katy Hays Summary, Characters and Themes

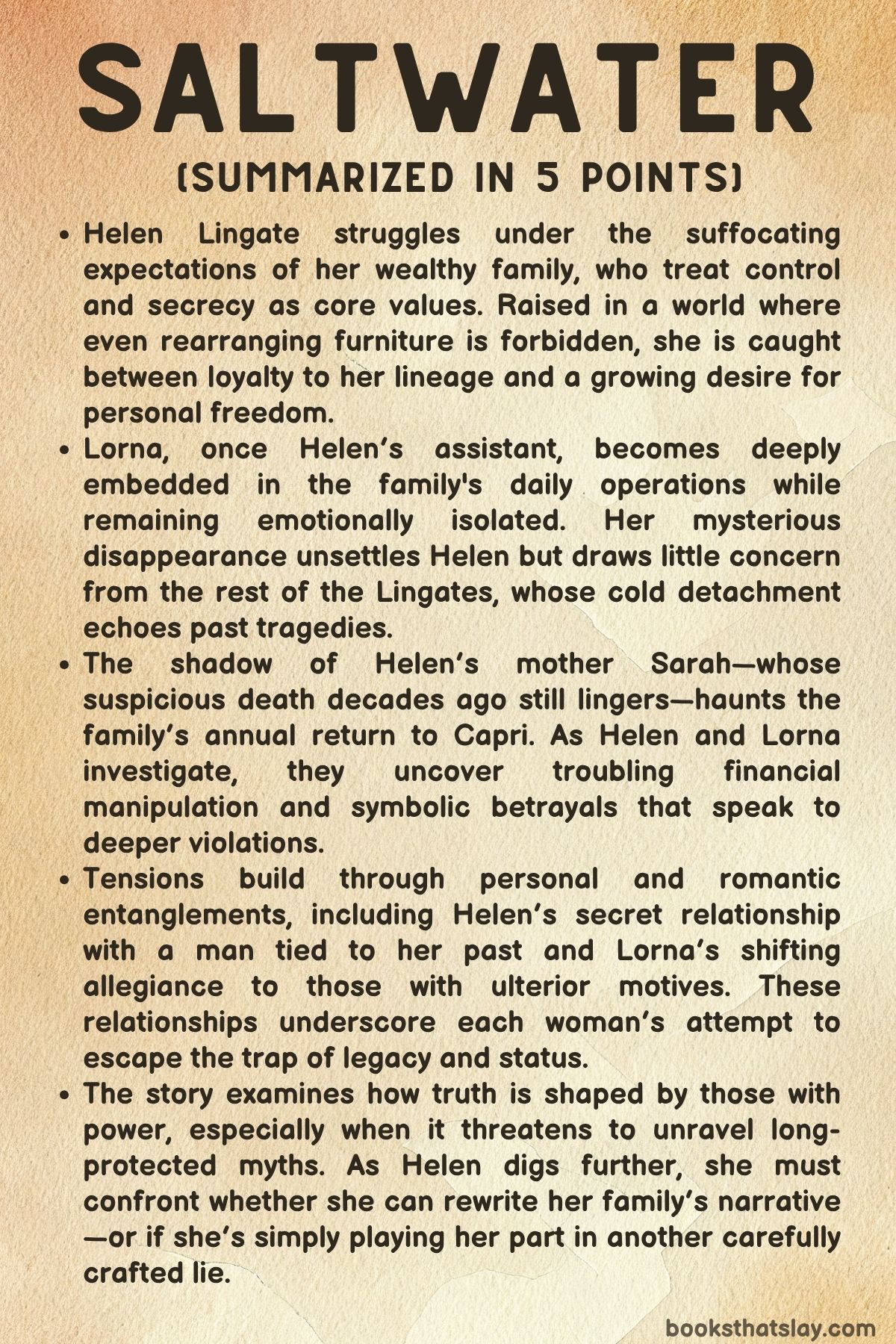

Saltwater by Katy Hays is a moody, psychologically intense novel set against the decadent backdrop of Capri, exploring the corrosive effects of wealth, secrecy, and familial control. At its center is Helen Lingate, an heiress tormented by the legacy of her powerful family and the shadow of her mother’s mysterious death.

The story charts a few suffocating days of revelations and unravelings, as Helen and her assistant Lorna—equally complicit and entrapped—conspire to expose long-buried truths. The novel unfolds like a quiet reckoning, where the ghosts of the past threaten to resurface and silence those who dare to confront them. It is a meditation on control, complicity, and survival in the face of generational rot.

Summary

Helen Lingate, heir to an oil fortune, spends summers in Capri with her powerful and secretive family. Despite the dazzling setting, the atmosphere is dominated by tension, control, and a history of loss.

Helen’s mother, Sarah, died decades earlier after falling from a cliff on the island—a death clouded by rumors and unanswered questions. Each year, the family reenacts a carefully sanitized version of the past, and this summer, Helen arrives with a quiet plan to change that.

She is accompanied by Lorna, her assistant, who has slowly become a confidante and co-conspirator. Lorna is more than just an employee—she is a woman shaped by abandonment, drawn to the opulence and dysfunction of the Lingates.

Her role is both invisible and intimate. She helps orchestrate the family’s summer, manages crises, and keeps things tidy.

But beneath her efficient surface lies a deep understanding of the family’s secrets, especially surrounding Sarah’s death.

The family dynamics are warped and suffocating. Richard, Helen’s father, and Marcus, her uncle, exercise total control over the household.

Everything is monitored, and deviation from the script is punished with cold dismissal. Helen lives under their shadow, her freedom stifled despite her adulthood.

She once had a trust fund set up by her mother, but it was quietly stolen by her father—an act of financial and emotional betrayal. When a long-lost necklace of Sarah’s mysteriously arrives in the mail, Helen and Lorna use its reappearance to initiate a scheme that might finally rupture the family’s control.

As the days pass, Lorna’s presence begins to stir old anxieties. She has spent months researching Sarah’s death, noticing inconsistencies and silent omissions.

She becomes more than a helper; she is a witness, a potential threat. Tensions heighten as the family shows signs of unraveling.

Freddy, Helen’s cousin, grows erratic. Naomi, her aunt, lashes out with bitterness.

Meanwhile, Helen rekindles a secret romance with Ciro, the housekeeper’s son—a connection rooted in childhood and renewed by desperation.

The plan between Helen and Lorna is simple but dangerous: use the necklace to force the family into exposure. But as events spiral, Lorna disappears.

One morning, her bed is unslept in, and her absence is met with unsettling calm. Helen is horrified by the family’s indifference, which echoes their reaction years ago to her mother’s death.

Lorna is gone, and no one seems to care.

In the hours before her vanishing, Lorna had roamed the island, her thoughts churning. She had visited the nightclub Anema e Core, where Helen had been drinking with Freddy.

Helen had slipped away to meet Ciro, an intimate betrayal that left Lorna reeling. She considered her options: escape, exposure, or disappearance.

She walked through alleys, was followed by men, and then seemed to vanish into the dark—either saved or taken, the reader cannot be sure.

When Helen returns from the sea, her mind is fragmented. She thinks she sees Lorna in the distance, but it may be a hallucination.

News arrives that Lorna’s body has been found. At the same time, Sarah’s death is being re-investigated as a possible homicide.

Helen suspects everyone—her father, Marcus, Freddy, even Ciro, who has a suspicious wound on his hand. The family rushes to fabricate alibis, hiding behind their wealth and charm.

The confrontation begins with Helen’s father finishing a draft of Sarah’s old play, Saltwater. The work contains painful truths, including accusations that Marcus left Sarah to die.

At a party, the men argue over its content. Marcus admits its accuracy: Sarah was injured and abandoned by the family to protect their name.

Naomi had been the orchestrator, whispering manipulations and pushing for silence.

Things spiral when Marcus tries to bribe Helen into silence by offering her Lorna’s personal effects, including a fake ID and travel plans. Later, a fight erupts between Marcus and Richard near the cliffs, and Marcus falls to his death.

Helen lies to the authorities, claiming it was an accident.

Naomi, drunk and unraveling, confesses her own role in Sarah’s death. Motivated by jealousy and control, she had ensured Sarah received no medical help after being injured.

Helen, finally pushed past the limits of compassion, slips poison into Naomi’s drink. Naomi dies, and Helen lets the assumption of suicide stand.

The story then takes a staggering turn. Renata, the longtime housekeeper and Ciro’s mother, reveals herself as Sarah.

She had survived the attack decades earlier and lived in hiding under a new identity. Her return was prompted by Helen’s actions and Lorna’s reappearance of the necklace.

She had raised Ciro as her own and remained close to Helen every summer, silently watching.

Two years later, Helen lives in Milan with Ciro and their son Aaron. The Lingate estate is gone, and with Naomi’s wealth, Helen is financially free.

But freedom comes with its own shadows. She sees Lorna again—alive.

Lorna had faked her death, using a body double, disappearing with the resources and cunning she had gathered over the years. She, too, had to vanish to survive.

The final moments of the novel reflect on transformation. Helen is not unscathed.

She is hardened, aware of what it took to free herself. The family that once dictated her every movement has dissolved.

But the cost was high: death, disappearance, deception. The women in this story—Sarah, Helen, Lorna—each had to reinvent themselves to escape the machinery of wealth and control.

In doing so, they claimed their own stories, even as they erased their former lives. The price of liberation was steep, but in the end, they were no longer living under someone else’s legacy.

They had written their own.

Characters

Helen Lingate

Helen Lingate stands at the center of Saltwater as both narrator and unreliable architect of her own fate. Raised amidst immense wealth and rigid expectations, Helen embodies the contradictions of privilege: outwardly elegant and composed, inwardly fractured and uncertain.

Her identity is defined by the immense control exerted by her father Richard and uncle Marcus, who police her every decision under the guise of protecting the family name. Though she enjoys the trappings of luxury, she is not free—her financial autonomy is stolen when her inheritance is secretly liquidated, and her romantic relationships are surveilled and discouraged.

Helen longs to break free but has internalized the very control she resents, replicating it in her own schemes and manipulations. Her relationship with Lorna becomes a lifeline—one part alliance, one part confession booth, and one part ticking time bomb.

As the story progresses, Helen’s perception of reality begins to blur, particularly in the wake of Lorna’s disappearance and the reemergence of family ghosts, both literal and metaphorical. Her eventual transformation into a woman capable of poisoning Naomi and covering up multiple deaths suggests that survival has hardened her into someone capable of immense calculation.

And yet, her capacity for love—especially toward Ciro and their son—remains, hinting at a redemptive possibility beneath the surface of a deeply scarred psyche. Helen’s journey is that of a woman seeking autonomy in a world designed to deny it, even if the price is blood and betrayal.

Lorna

Lorna serves as both foil and mirror to Helen, a woman who begins as an employee and ends as something more elusive: a ghost, a conspirator, and finally, a survivor. Hired as Helen’s assistant, Lorna initially plays the role of the invisible woman—the one who cleans up messes, organizes chaos, and fades into the background when not needed.

But beneath this compliant surface lies a woman with her own unresolved traumas and ambitions. Lorna is drawn to the Lingates not just for the proximity to wealth, but for the sense of purpose and belonging they represent.

However, she remains deeply aware of her outsider status and is constantly maneuvering for leverage. Her attachment to Helen shifts from loyalty to manipulation as she begins orchestrating her own exit strategy, culminating in a plan involving stolen jewelry, faked deaths, and ambiguous moral choices.

Lorna’s final act—disappearing and impersonating another woman to escape—is a radical assertion of autonomy in a world where women like her are often used and discarded. Her survival hinges on deception, much like Helen’s, and yet her trajectory feels more liberating.

Lorna escapes the family’s web entirely, while Helen remains haunted by its shadows. In the end, Lorna is both cautionary tale and symbol of reinvention—a woman who took control of her story by rewriting it completely.

Richard Lingate

As Helen’s father, Richard is the enforcer of tradition, secrecy, and control in the Lingaite dynasty. He represents a patriarchal model of power: emotionally repressed, strategically ruthless, and profoundly invested in preserving appearances.

Richard’s manipulation is subtle and systematic—he doesn’t rage, he erases. By liquidating Sarah’s trust and burying the truth of her death, he effectively erases the autonomy of both his wife and daughter.

Yet Richard is not entirely devoid of emotion. His collaboration on Sarah’s unfinished play and his eventual confession of guilt to Helen reveal a buried conscience.

In a tragic irony, he is responsible for the most devastating acts of silence in the novel, yet he cannot escape his own grief and shame. His death—marked by a physical confrontation and a symbolic fall—suggests a reckoning with the past he tried to control.

He is a man who wielded power to protect his family but destroyed them in the process. Richard is not simply villainous; he is a tragic figure undone by his inability to adapt, and by a love for control that outweighed his love for truth.

Marcus Lingate

Marcus is Richard’s brother and the family’s second shadow patriarch, embodying the same traits of control and deception, though with more visible cracks. Where Richard maintains a veneer of calm, Marcus is more openly manipulative and less emotionally controlled.

His role in covering up Sarah’s death and attempting to bribe Lorna shows that he, too, is willing to cross moral lines to protect the family’s image. His eventual confrontation with Richard, in which he confirms the truth behind Sarah’s murder, results in his accidental death—a moment that symbolizes the crumbling of the family’s moral facade.

Marcus is the character who perhaps understands best the cost of the family’s silence, yet he remains complicit. His death, unlike Richard’s, feels like a collapse of guilt and rot rather than a moment of reckoning.

Marcus is the embodiment of the family’s internal decay—a man who knew the truth but chose convenience over conscience.

Naomi

Naomi is the dark heart of the Lingaite family, a woman whose charm masks a ferocious will to dominate. Initially presented as a glamorous matriarch, she is later revealed to be the true architect of Sarah’s death.

Her confession to Helen—that she manipulated Marcus into letting Sarah die and has hated Helen for embodying Sarah’s spirit—recasts her as the novel’s most chilling figure. Unlike the men in the family, Naomi acts with cold precision and emotional detachment.

Her death by poisoning, orchestrated by Helen, mirrors the methodical cruelty she herself employed decades earlier. Naomi is the purest representation of what power looks like when divorced from empathy.

She clings to status and influence even as the truth crumbles around her, and her final downfall is both poetic and brutal. Naomi’s legacy is one of calculated harm masked as familial duty, and in the end, her destruction feels like a necessary purge.

Sarah Lingate / Renata

Sarah is the ghost who haunts every page of Saltwater, a woman presumed dead but revealed to be alive, living under the name Renata, the family’s longtime housekeeper. Her transformation from victim to silent observer is one of the novel’s most powerful twists.

Left for dead by Naomi and Marcus, Sarah chose exile over confrontation, raising Ciro and watching Helen from afar for decades. Her silence is both tragic and strategic—she allowed herself to become invisible in order to survive.

Her reemergence complicates the narrative of victimhood; she becomes a woman who reclaimed power by withdrawing from it. Sarah’s presence reframes the entire novel, adding layers of irony and sorrow.

That she helped raise Helen under a false identity, and only revealed herself after the family imploded, is a testament to both her trauma and her enduring strength. Sarah is the true matriarch—resilient, resourceful, and ultimately redemptive.

Ciro

Ciro is the emotional heartbeat of the novel, a character who embodies sincerity, loyalty, and unexpected strength. Initially introduced as a childhood friend and secret lover of Helen, he is later revealed to be Sarah’s adopted son, raised in the shadows of the Lingate estate.

Ciro offers Helen a glimpse of life outside the gilded cage of wealth and manipulation, and their bond—sexual, emotional, and eventually familial—grounds the story in something tender and human. However, Ciro is not without complications.

His proximity to Lorna before her disappearance raises suspicions, and his loyalty to his mother Sarah adds a layer of moral ambiguity to his role. Ultimately, Ciro is a bridge between the old world and the new, between the haunted legacy of the Lingates and the possibility of renewal.

His relationship with Helen and their son Aaron represents a kind of rebirth, albeit one still haunted by the past.

Freddy

Freddy, Helen’s cousin, is a minor but potent embodiment of inherited rot. Groomed as the heir to the Lingaite fortune, Freddy exudes entitlement, arrogance, and emotional vacancy.

His interactions with Helen and Lorna suggest a man unbothered by the moral weight of his family’s actions. He moves through the world insulated by wealth, prone to indulgence and dismissiveness.

Freddy’s role in Lorna’s final night, his complicity in the family’s silence, and his general attitude of detachment reinforce the story’s theme that wealth does not just corrupt—it anesthetizes. Freddy is not a villain per se, but he is emblematic of a generation raised without accountability, a man who contributes to the cycle of erasure simply by refusing to see what is in front of him.

Stan

Stan is a minor but critical presence, a figure lurking on the periphery of the story as a reminder of danger and leverage. Tied to Lorna through ambiguous connections, he represents the threat of exposure and the external consequences of internal family crimes.

His pursuit of information—and possibly blackmail—adds tension and a sense of surveillance to Lorna’s experience. Stan is a specter of a different kind of power, one not inherited but seized.

Though he never becomes a central antagonist, his presence underscores the fragility of the world the Lingates have built. In a family where reputation is currency, Stan is a man who threatens to bankrupt them all.

Aaron

Aaron is the child of Helen and Ciro, introduced only at the novel’s end but symbolizing everything that has shifted. His existence marks a break from the past—a union between Sarah’s secret life and Helen’s attempt at freedom.

Aaron represents not just the continuation of the bloodline but a potential future unshackled by the sins of his ancestors. His presence brings an emotional gravity to Helen’s choices, forcing her to consider what legacy she wants to leave behind.

While he does not take part in the narrative’s action, Aaron’s role as a symbolic anchor is crucial. He is the embodiment of what survival, love, and reinvention might look like, even in the aftermath of violence and betrayal.

Themes

Wealth as a Force of Corruption and Narrative Control

In Saltwater, wealth is not merely a backdrop but a generative force that shapes behavior, distorts perception, and erases consequences. The Lingate family’s money affords them the power to manipulate reality—suppressing scandals, reconfiguring personal histories, and eliminating threats, even if those threats are individuals.

Their wealth is steeped in crime, dating back to the fraudulent acquisition of oil leases that established their fortune. Yet, the money continues to act not just as a privilege but as a liability—binding Helen and others in a web of coercion and complicity.

The characters do not live freely; they orbit around the gravitational pull of their family legacy, where every relationship is transactional and every gesture is calibrated for appearances. The family myth becomes a curated product, carefully maintained through strategic silences and rehearsed versions of the past.

Even grief, such as in the case of Sarah’s death, is rehearsed, cleaned, and pressed into the mold of respectability. The grotesque irony is that their wealth, which should have empowered liberation, becomes the primary mechanism of imprisonment.

Helen’s own efforts to challenge this through the reappropriation of the family story—especially in finishing her mother’s play—are themselves tainted by the very power she seeks to dismantle. The story ultimately positions wealth not just as corrupting, but as a systemic force capable of rewriting truth, suppressing justice, and rewriting the lives of everyone who comes into its reach.

Gendered Violence and the Erasure of Women

The deaths, disappearances, and silencing of women in the Lingate family are not anomalies—they are institutionalized consequences of a system that permits men and complicit women to maintain control. Sarah’s fall from a cliff, long ruled an accident, is eventually revealed as an orchestrated act of violence.

Naomi’s confession exposes a chilling truth: that Sarah was intentionally left to die to preserve family power and hierarchy. Naomi herself, despite being a woman, becomes a collaborator in this violence, driven by jealousy, internalized misogyny, and a hunger for control.

Lorna’s disappearance repeats the cycle—another woman whose threat to the family’s carefully curated legacy is answered with presumed elimination. Even when Lorna turns out to be alive, her vanishing must be understood as survival through erasure.

Her only option for agency is to disappear, to fake her death and assume another life. Helen too must engage in violence and deception to carve out autonomy.

The toxic cost of femininity within this environment is that to survive, women must either comply, vanish, or become ruthless. This gendered dynamic is emphasized through repeated motifs of surveillance, inheritance theft, and emotional neglect, all of which disproportionately affect the women of the story.

The narrative is filled with women being punished for knowing too much, wanting too much, or simply refusing to perform silence. Their stories are overwritten by others—until they find ways, often through morally grey or criminal acts, to write themselves back in.

Legacy, Guilt, and Intergenerational Trauma

At the heart of the story is the inheritance not of wealth, but of harm. Helen inherits more than a fortune; she inherits an identity forged by secrecy, control, and generational manipulation.

Her mother’s silence, her father’s domination, and her family’s systemic rewriting of the past all shape her understanding of self and truth. The trauma inflicted upon Helen is not just personal—it is cultural within the family.

The control exercised by Richard and Marcus over every aspect of her life is a reflection of how power is handed down: through stories that reinforce obedience, through fear disguised as care, and through economic manipulation dressed as inheritance. Even the family estate, with its unchanged furniture and ritualistic returns to the place of Sarah’s death, functions as a mausoleum of unresolved trauma.

Helen’s arc involves not merely uncovering the truth, but confronting the weight of the past that seeks to define her. She ultimately becomes both perpetrator and victim of this legacy.

Her killing of Naomi, while framed as liberation, also represents a continuation of the family’s cycle of secrecy and silence. There is no clean break from legacy here—only a reshaping of its terms.

The novel critiques the impossibility of moral clarity when one’s lineage is built upon exploitation, theft, and denial. Trauma in Saltwater is not just psychological; it is architectural, embedded in the structures of the family and the spaces they inhabit.

The Illusion of Autonomy in Enclosed Systems

Though Helen appears to have moments of decision-making power—her relationship with Ciro, her schemes with Lorna, her rewriting of her mother’s play—these acts are always surrounded by the question of whether she is ever truly free. Her family’s surveillance is psychological as much as physical, internalized in her hesitation, guilt, and need for approval.

Lorna’s arc mirrors this dynamic. Hired into a system she believes she can navigate from the outside, she becomes so entangled that escape requires not resignation but performance, crime, and disappearance.

Even Ciro, ostensibly a free agent outside the family, is bound by his proximity to them through his mother Renata—who is later revealed to be Sarah herself. The revelation that Sarah chose self-erasure in order to survive completes this theme: the only true autonomy within such a closed, predatory system lies in disappearance.

Yet even that disappearance is partial—Sarah stayed close as a housekeeper, Lorna faked her death but continued to watch. Autonomy in Saltwater is a performance, often brief and illusory.

The most powerful characters maintain control not by expressing freedom, but by choreographing the freedoms of others. The novel illustrates how every act of rebellion is shadowed by a system capable of neutralizing it or absorbing it into its mythology.

True freedom, if it exists at all, is unstable, hard-won, and leaves scars of both complicity and survival.

Justice and Moral Ambiguity

Throughout the story, questions of justice are raised but never resolved in absolutes. The murder of Sarah, the disappearance and supposed death of Lorna, the accidental killing of Marcus, and the poisoning of Naomi each bring forth moral dilemmas.

There is a consistent blurring of lines between justice, revenge, and self-preservation. Helen does not expose her family through legal or ethical means—she subverts them through manipulation and quiet violence.

The story critiques not only the failure of legal systems but also the impossibility of clean justice within corrupt institutions. Even the re-investigation of Sarah’s death by authorities is framed as a formality, more reactive than revolutionary.

Lorna’s ability to escape is not a triumph of justice but of cunning. In this world, justice is privatized, shaped by personal ethics and family codes rather than societal ones.

What makes these events chilling is not just the crime, but the cold rationality behind them—the calculation of who deserves to live, who deserves silence, and who is expendable. Helen, once paralyzed by fear and loyalty, grows into a woman capable of murder in the name of protection and truth.

But the novel never frames her as heroic. Her choices are soaked in ambiguity, leaving the reader unsure whether the final liberation she achieves is a moral victory or just a new iteration of her family’s long history of secrets and control.

The closing scene, with Helen wealthy, partnered, and a mother, is not triumphant but haunting, defined by absence and the weight of what it took to reach that point.