Saving the Rain Summary, Characters and Themes

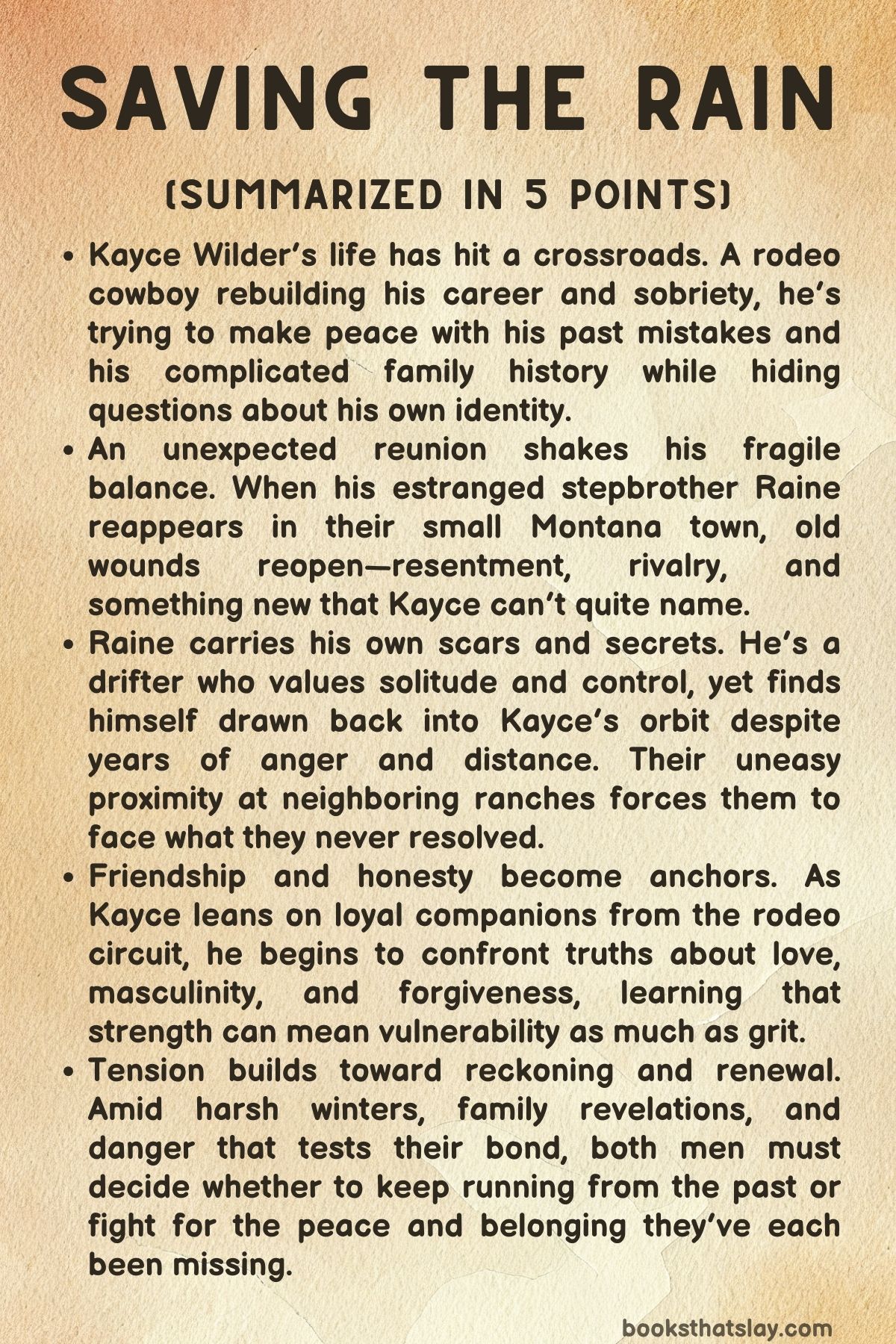

Saving the Rain by Elliott Rose explores redemption, love, and identity against the rugged backdrop of rural Montana and the adrenaline-charged world of rodeo. The novel follows Kayce Wilder, a professional cowboy struggling to stay sober and rebuild his life, and his estranged stepbrother, Raine Rainer, whose return to their small town reopens old wounds and awakens forbidden feelings.

Through emotional introspection, family conflict, and a romance that challenges social and personal boundaries, the book portrays two men learning to face their pasts and embrace vulnerability. It’s a story about confronting pain, accepting truth, and finding peace in unexpected places. It’s the 4th book in the Crimson Ridge series by the author.

Summary

The story begins at a bonfire after a rodeo at Rhodes Ranch. Kayce Wilder, a seasoned cowboy, is celebrating with his close-knit group of friends—Chaos Hayes, Brad, and Brad’s boyfriend, Flinn.

Beneath the laughter and teasing, Kayce hides an internal struggle. Months earlier, a spontaneous kiss with another man forced him to question his sexuality.

Now sober and trying to hold his life together, he feels uneasy when his friends notice an unfamiliar cowboy across the fire. When Kayce approaches to grab a drink, he realizes the man is Raine Rainer—his estranged stepbrother, a ghost from his painful past.

Their reunion is bitter and tense, marked by old resentment and unresolved anger.

The next morning at Devil’s Peak Ranch, where Kayce lives with his father Colton, he reflects on the turmoil that shaped him. Years ago, his mother married Ezekiel Rainer Sr., a cruel man whose son Raine tormented Kayce throughout their teenage years. When that marriage collapsed, so did Kayce’s sense of stability.

Later, he reconnected with his biological father, discovering a man far removed from the villain his mother had described. Living and working alongside Colton helped him regain control after years of reckless behavior and addiction.

Still, memories of Raine linger, complicated now by the attraction Kayce felt at the bonfire before recognizing him. His confusion over his sexuality deepens, and though he suspects he might be bisexual, shame and fear keep him silent.

Meanwhile, Raine’s life unfolds at Sunset Skies Ranch, where he has taken a temporary job. Solitary and blunt, he prefers hard work to conversation.

His run-in with Kayce at the bonfire still rankles him, stirring emotions he doesn’t want to name. His boss’s sister, Tessa Heartford, treats him with friendly warmth, showing that beneath his rough edges lies a loyal, protective nature.

But when he crosses paths with Kayce again during a trail ride, old hostilities ignite. Their exchanges are sharp and defensive, but underneath the verbal sparring lies tension neither can deny.

Over the following weeks, their lives intersect repeatedly. Kayce continues competing in rodeos while balancing work at the ranch, determined to keep his sobriety intact.

During one competition, he delivers a flawless ride that reminds him why he loves the sport. Yet victory brings no peace—his thoughts keep returning to Raine.

When Kayce finally confides in his friend Brad about his attraction to men, Brad responds with understanding, encouraging him to accept his feelings rather than fear them. Their conversation marks Kayce’s first step toward honesty.

That night, Kayce reluctantly attends a celebration at The Loaded Hog, the local bar. The atmosphere is lively, but his mood sinks when he spots Raine among the crowd.

Overwhelmed, Kayce steps outside for air and meets a friendly young man who seems interested in him. Before he can process what’s happening, Raine interrupts, angrily snuffing out the stranger’s cigarette under the pretext of protecting Kayce’s health.

The confrontation turns ugly, reviving years of resentment and humiliation. When Raine walks away with another woman, Kayce feels both anger and an inexplicable pang of jealousy.

Days later, fate throws them together again when Kayce shows up at Raine’s loft during a cold, misty night. Soaked and emotionally exhausted, he admits he had nowhere else to go.

Raine lets him in, and amid the warmth of the small cabin, their defenses crumble. What begins as confrontation shifts into confession—Kayce revealing his confusion, Raine admitting his frustration—and ends with an intense night of physical and emotional connection.

Their encounter, though tender and raw, leaves them uncertain of what comes next.

In the days that follow, they begin texting hesitantly, testing boundaries with teasing messages that turn into open invitations. Kayce asks Raine to visit Devil’s Peak, and when he arrives, their reunion carries a quieter intimacy.

Their conversations are filled with awkward honesty and unspoken desire. Slowly, they allow themselves to explore what their relationship could mean, balancing humor and vulnerability.

For the first time, both men feel seen and accepted.

Kayce’s growth continues as he reconciles with his father and begins therapy. He starts facing painful truths about his past—his mother’s neglect, his own self-destructive choices, and the deep fear of not being enough.

When his mother reaches out again seeking money, he resists the familiar cycle of guilt and instead arranges for her to enter rehab. In response, she reveals a shocking truth: Raine had once protected them from Ezekiel’s abuse, taking the beatings himself and later threatening his father to keep them safe.

The revelation reframes everything Kayce thought he knew about his stepbrother. Moved and heartbroken, he messages Raine, who finally breaks his silence by posting a photo of them together with the caption “Never not obsessed with you.

As winter deepens, Kayce and Raine’s bond strengthens. When Raine unexpectedly arrives at Devil’s Peak through the snow, they decide to stop running from their feelings.

They spend weeks together in isolation, working side by side on the ranch, sharing meals, and rediscovering a sense of peace neither thought possible. But their calm is shattered when Ezekiel reappears at the ranch, armed and furious.

He threatens to destroy everything, and when Raine intervenes, a violent struggle ends with him being shot. Despite his injuries, Raine overpowers his father and protects Kayce once again.

Kayce calls for help and stays by Raine’s side as emergency responders arrive. The incident forces long-suppressed truths into the open.

Ezekiel is arrested, and Raine undergoes surgery, clinging to life. Kayce’s father, Colton, rushes home to support him, and the two men strengthen their bond through shared fear and love.

When Raine finally wakes, Kayce is there, confessing his love. Their friends and family rally around them, accepting their relationship without hesitation.

Months later, in the epilogue, summer returns to Montana. At a bonfire surrounded by friends, Kayce watches Raine, now healed and smiling, across the flames.

Raine gifts him a smooth stone he once carried for comfort, followed by a velvet box holding two engraved rings. In the quiet glow of evening, Raine asks Kayce to let him stay by his side forever.

Kayce says yes before the words are fully spoken. Surrounded by the people who once doubted their happiness, the two men walk hand in hand toward the light, ready to start their life together as husbands.

Characters

Kayce Wilder

Kayce is the beating heart of Saving the rain, a professional bronc rider clawing his way back from addiction, bad press, and a wrecked knee toward a quieter, truer life. His arc is a study in shame giving way to self-acceptance: the man who once wore charm and competitiveness like armor learns to name his desire, trust his instincts, and ask for help.

Work grounds him; the rhythm of Devil’s Peak Ranch and his meticulous care for horses mirror his need for control after years of chaos. Yet control is also his cage, and the stepbrother he believes he despises becomes the catalyst who forces him to live in his body rather than in fear.

Kayce’s tenderness shows in the way he protects friends, manages his asthma without drama, and refuses to bankroll his mother again while still securing rehab; his courage shows when he comes out, retires from rodeo, and stays present through Raine’s surgery. Love does not magically fix him; instead, it gives his sobriety a purpose beyond survival and turns his impulse to run into a decision to remain, build, and belong.

Zeke “Raine” Rainer

Raine is the book’s flint and its unexpected shelter, a drifter foreman who trusts routines, not people, and who has learned to preempt pain by moving on. The persona—gruff, sardonic, hypercompetent—conceals a private code of care so strict it borders on self-erasure: as a teen he baited his abusive father to draw harm away from Kayce and Kayce’s mother, and as an adult he keeps distances to ensure he can’t fail anyone.

With Kayce he is both mirror and match; he respects competence, prizes consent, and translates intimacy into practical acts—checking an injury, lighting a fire, texting after a storm. His jealousy reads first as contempt, then as the ache of a man who has never learned to want openly.

The shooting crystallizes his arc: he chooses protection without disappearing afterward, quits running jobs, and trades the safety of exit plans for the risk of permanence. By the time he places the mountain-engraved rings in Kayce’s palm, Raine has reframed authority as devotion and possession as a vow to keep showing up.

Colton Wilder

Colton embodies second chances done right. Once an absent young father lost in his own missteps, he now offers steadiness without control, respecting Kayce’s autonomy while keeping the door—and the fire—lit.

Their phone calls and quick reassurances prove that repair is often quiet work, made of showing up on long nights and taking the first flight when things go wrong. Colton’s presence at the hospital and his willingness to partner with Layla from afar show a masculinity that refuses the ruts of pride or denial; he models how to love an adult child without owning them, and his ranch becomes the literal ground where Kayce and Raine can risk a future.

Kayce’s Mother

Kayce’s mother is the story’s most complicated wound, a woman whose addiction and poor choices ripple through every room her son enters. She triangulates, manipulates, and asks for money, yet her confession about Raine’s covert protection reframes the past and, ironically, becomes a gift that enables healing between the men she hurt most.

Kayce’s refusal to fund her while arranging rehab is a boundary drawn in love rather than anger, underscoring the novel’s insistence that caregiving without limits becomes complicity.

Ezekiel Rainer Sr.

Ezekiel is abuse given momentum, a man who uses authority to humiliate and harm and later returns with a gun and a gas can, literalizing the threat he has always posed. His attempted terror on Devil’s Peak forces the family and found-family systems to mobilize, and his maiming at Raine’s hands is both a grim reckoning and a line the story refuses to cross back over; after this, violence no longer functions as power but as consequence.

He exists not to be redeemed but to be stopped, and the narrative obliges.

Chaos Hayes

Chaos is Kayce’s foil in kinetic form—another elite rider who embodies acceptance so casually it looks like bravado. He teases, rallies the crew, runs a bar with his brother, and grants Kayce the kind of social permission that closeted people study for cues.

His nickname fits his spark, but beneath the noise is reliability; he is the friend who gossips and then quietly offers a ride, the competitor who knows that excellence means nothing if you can’t bring your people along.

Brad

Brad is the friend who makes honesty feel survivable. As a bisexual man, he normalizes Kayce’s confession without turning it into a seminar, tempering gravity with humor and offering what Kayce most lacks—an uncomplicated mirror.

His presence proves that community isn’t only who shows up at the hospital; it’s also the one person at the arena who lets you say the unsayable and then keeps your secrets safe.

Flinn

Flinn, Brad’s boyfriend, extends the circle of safety. He doesn’t need a showcase moment to matter; his very ordinariness—showing up, celebrating wins, being affectionate in public—offers Kayce a benign blueprint for queer domesticity in a place that still smells like dust and saddle soap.

Tessa Heartford

Tessa is the ranch’s steady barometer, cheerful and pregnant but not fragile, managing growth with spreadsheets in one hand and empathy in the other. She reads people clearly, sees through Raine’s deflections, and refuses to confuse optimism with naivete.

By treating both men as already worth rooting for, she lends social legitimacy to a bond that begins in secrecy and heat.

Beau Heartford

Beau’s legacy is infrastructure: a well-run operation, good horses, and a culture of care that lets a man like Raine function at his best. Offstage for stretches, he still shapes the moral weather; standards are high, corners aren’t cut, and loyalty is expected to run both ways.

Storm

Storm, the farrier, manifests competence with a gentle edge. The way he partners with the ranch and with Briar, miniature pony in tow, underscores a theme the novel returns to again and again: craft is love made visible.

His easy generosity with time and tools keeps the place—and by extension, its people—sound.

Briar

Briar’s warmth and comic asides soften hard scenes and make community feel textured rather than symbolic. Her presence alongside Storm and Willow reminds the reader that chosen families are built from a hundred small rituals, not a single grand gesture.

Jessie

Jessie begins as the heterosexual script Kayce thinks he should inhabit and ultimately becomes a marker of his growth. The flirtation he cannot sustain is less a rejection of her than of the lie he’s been telling himself; the story treats her with respect by not converting her into punishment or temptation.

Oscar

Oscar’s victory party sets a stage where joy and discomfort collide, placing Kayce’s private crisis inside a public celebration. He is a reminder that success cannot mute dissonance, and that the rodeo world contains both the old codes and the people already living beyond them.

Knox Hayes

Knox co-creates the civic square at The Loaded Hog, a space where rivalries cool and alliances form. By running a bar that welcomes the whole tangle of ranch hands, riders, and locals, he helps normalize Kayce and Raine’s presence long before anyone articulates what they are to each other.

Sheriff Cam Hayes

Cam embodies lawful care, moving with crisp efficiency from arresting Ezekiel to stabilizing a scene that could have spiraled further. He isn’t a savior so much as the community’s spine, and his intervention lets the narrative pivot from survival back to recovery.

Layla

Layla, Colton’s partner, is proof that blended families can be mended without erasing what broke them. Her support from abroad thickens the network around Kayce, showing that love at a distance still counts as love that holds.

Sage

Sage’s presence among the hospital visitors widens the lens on the town’s empathy. She functions as a chorus member in the novel’s final movements, one more voice affirming that visibility is safer when many people keep watch.

Mist

Though a horse, Mist operates as an emotional instrument for Raine, the deliberate ride he takes when words won’t do. The Blue Roan’s steadiness externalizes Raine’s competence and gives him a way to metabolize feeling without spectacle, making the animal an extension of his inner discipline.

Willow

Willow, the miniature pony glued to Storm, adds levity that the story smartly allows. In a book where bodies carry scars, a small, stubborn companion moving from scene to scene reads like a charm against despair and a reminder that tenderness comes in many sizes.

Themes

Coming to Terms with Desire and Selfhood

Kayce’s arc in Saving the rain is powered by a slow, often painful recognition of what he wants and who he is. The bonfire jolt—being drawn to a stranger who turns out to be Raine—doesn’t inaugurate his questioning so much as force him to stop dodging it.

He has already kissed a man on New Year’s, already felt something click into place, already sensed that the old performance of the woman-chasing rodeo star never really fit. What the story records is the daily labor of self-knowledge: the uneasy jokes with friends that conceal dread, the barn chores that offer temporary numbness, the reflex to disappear into work whenever emotion rises.

His coming out to Brad isn’t a trumpet blast; it’s tentative, embarrassed, and practical, the way people actually confess the thing that could shift every relationship they maintain. The text lets him hesitate without mocking him, and it also lets him be thrilled—by the eight-second perfection on a bronc, by a first kiss that feels like honesty, by the steadiness of being seen and not scorned.

Crucially, desire here isn’t abstract. It is embodied, grounded in asthma warnings, sore knees, wet flannel, and the gritty logistics of ranch life.

That concreteness protects the story from cliché: Kayce’s sexuality isn’t a declaration posted to the sky; it’s a series of choices made in pickup cabs, shower stalls, and text threads. The eventual clarity he reaches—naming himself, choosing Raine, telling friends, inviting tenderness—reads less like a switch flipped and more like a skill learned.

He practices it across scenes until selfhood feels wearable. The point isn’t identity as label; it’s identity as the freedom to stop apologizing for what brings him peace.

Found Kinship, Broken Homes, and the Work of Repair

Family in Saving the rain isn’t a tidy genealogy; it’s a battlefield and then a workshop. Kayce’s childhood through Ezekiel Rainer Sr.

is marked by ridicule, fear, and a constant readiness to brace. Raine’s presence in that house complicates the usual villain/hero split.

As boys they were hostile and competitive, yet adulthood reveals that Raine directed danger away from Kayce and his mother, taking blows, negotiating with a violent man, and eventually drawing a line that held. That late disclosure reframes years of bitterness, exposing how trauma can disguise protection as cruelty.

Parallel to that, Kayce’s reunion with Colton substitutes a working definition of fatherhood—show up, put your hands on the hard jobs, make amends when you’ve failed—for the feints and excuses that defined his earlier home. The novel treats repair as continuous maintenance: calls across time zones, small affirmations, simple meals together, and the humility to accept help without feeling owned by it.

The community around Rhodes Ranch and Sunset Skies functions as a pressure relief valve and a training school for gentler forms of kinship. Tessa, Beau, Storm, Briar, Chaos, Brad, and others offer ordinary witnesses who normalize Kayce and Raine’s bond by doing very little except making room for it.

Even the hospital vigil near the end isn’t staged for spectacle; it’s a chorus of people who have learned, through years of hay, muck, and ice, that survival is a group project. When Ezekiel returns with a gun, the story recognizes that pasts don’t politely recede.

The victory is not the fantasy of a perfect family restored, but a workable network built. Kinship becomes consent to keep showing up, especially when the weather—literal and emotional—turns rough.

Masculinity, Power, and the Permission to Be Tender

Rodeo culture in Saving the rain supplies an ideal laboratory for examining masculinity because it’s all straps, spurs, and scoreboards on the surface, but what keeps a rider alive is sensitivity—minute adjustments, calm breathing, an ear for the animal under him. Kayce and Raine both embody that contradiction.

Kayce’s public face is the grinning competitor; his private life is a ledger of restraint: sobriety counted in days, cravings rerouted into chores, anger managed with long exhales in a tack room. Raine presents as gruff competence—hard hands, clipped speech, spare loft—yet he is meticulous in care: lifting laundry from a pregnant woman, counting the minutes in a stall until a skittish horse steadies, watching Kayce’s inhaler habits, and, later, reading his body with patience.

The book challenges an older script where “real men” only dominate. Here, authority is proved by attentiveness.

The sex scenes are not detours but arguments in another register; they show how gentleness can be explicit, how consent can be erotic, and how control can be shared rather than seized. When Raine says he won’t drive up the mountain to be dismissed, he isn’t posturing; he is setting a boundary that honors both of them.

When Kayce admits he likes being guided, he is not surrendering worth; he is naming what makes him feel safe. Their fights are similarly gendered experiments: raised voices, then the deliberate choice to step back rather than land a punch.

Even the final confrontation with Ezekiel refuses a cartoon of masculinity. Raine’s counterviolence is grim and costly, followed by collapse, surgeries, and a community response that centers care.

The novel’s thesis is simple: strength without tenderness is brittle; tenderness without strength is exposed. The men are at their best when they grant each other permission to be both.

Recovery, Accountability, and the Possibility of a New Story

Kayce’s sobriety gives Saving the rain its moral meter. Early on, he measures his days not by wins but by the steadying rituals that keep him clear: dawn air, the rhythm of feeding, the focus required by a skittish colt, the eight seconds of total presence on a bronc.

The book refuses the shortcut where love “fixes” addiction. Instead, Kayce’s recovery precedes and sustains intimacy.

He chooses not to drink at the bar, sets distance from his mother’s demands, and accepts that fame and sponsors won’t be his north star. Therapy sits quietly behind the scenes, not as miracle, but as structure: plans for boundary-setting, scripts for responding to manipulation, steps for reconciling with Colton without re-litigating the past.

Accountability shows up in smaller frames, too. Raine insists on clear yeses before sex, holds Kayce to promises about communication, and answers for his own choices by quitting a job rather than half-living in two places.

Even the rodeo sequences underline the theme. A perfect ride is not adrenaline worship; it’s disciplined craft.

You prepare, you breathe, you ride your plan, you accept the score and the soreness. Recovery mirrors that cadence: a string of deliberate acts, not a single grand gesture.

When Kayce books rehab for his mother instead of wiring cash, the narrative crystallizes its ethic: help is not the same as rescue, and love that refuses to underwrite harm is the most demanding kind. By the time the epilogue offers rings and a summer bonfire, the celebration feels earned because the story has made clear how many quiet, unglamorous decisions were required to arrive there.

Consent, Care, and Erotic Literacy

One of the most distinctive accomplishments of Saving the rain is the way it treats eroticism as a language two people learn together. The encounters are explicit, but their purpose is clarity rather than shock.

Scenes slow down around consent checks, around breath, around the difference between pressure and pain, around the aftercare of food, warmth, showers, and clean sheets. Raine’s directness is not coded dominance for its own sake; it’s pedagogy and reassurance, a way to reduce Kayce’s anxious forecasting by narrating what’s about to happen and why.

Kayce’s eagerness isn’t immaturity; it’s trust, the courage to ask for what works and admit what doesn’t. The novel also integrates health in understated ways—concern about asthma, attention to an injured knee, the discipline to stop and reposition rather than push through discomfort—so that sex sits inside a larger ethic of bodily stewardship.

Power dynamics are negotiated rather than presumed, and the writing honors the difference between secrecy and privacy. Their first night is clandestine because the feelings are new and frightening; later, boundaries shift toward openness, not because exhibition is a moral upgrade, but because hiding would contradict what they are trying to build.

Even jealousy and provocation are metabolized into conversation rather than tools to keep the other off-balance. By showing erotic literacy as a set of habits—ask, listen, verify, adjust—the book argues that intimacy is a craft.

Lovers are not fated; they are attentive apprentices to each other. The rings in the final scene are romantic, yes, but they also symbolize fluency acquired: two men who can read one another with competence and kindness.

Breaking the Cycle of Violence and Choosing a Future

The late arrival of Ezekiel with a gun gathers the book’s darker currents into a single crisis. Violence here isn’t aesthetic; it is blunt, disorganizing, and expensive.

The shot that tears into Raine’s abdomen ends any nostalgic temptation to excuse the past as “family trouble. ” Yet the scene also stages a decision about legacy.

Raine disables Ezekiel and stops, Kayce stabilizes the man he loves and calls for help, Sheriff Hayes arrests rather than improvises revenge, and a helicopter crew becomes the hinge between catastrophe and recovery. Institutions—law, medicine, community—are imperfect but necessary.

The cycle breaks not because a bigger alpha arrived, but because many people accepted roles that coordinated toward survival. Afterward, the narrative refuses to glamorize toughness.

Recovery is long, infection is a risk, and the hero moment is measured in hours spent in a waiting room, in learning how to be still with fear, and in letting other people feed you when you forget how. The revelation that Raine once baited his father to protect Kayce threads the past into the present calamity, converting what looked like teenage malice into a pattern of costly guardianship.

The epilogue’s quiet happiness—stone in a pocket, rings engraved with mountains, friends stringing lights—doesn’t cancel what happened; it crowns a choice. The men decide not to organize their lives around threat any longer.

They choose a future that keeps skills learned in crisis—vigilance, clear speech, collective care—but spends those skills on building, not bracing. The promise “never to walk away again” isn’t sentimental flourish.

It’s policy, drafted in scars, specifying how this family intends to operate from now on.