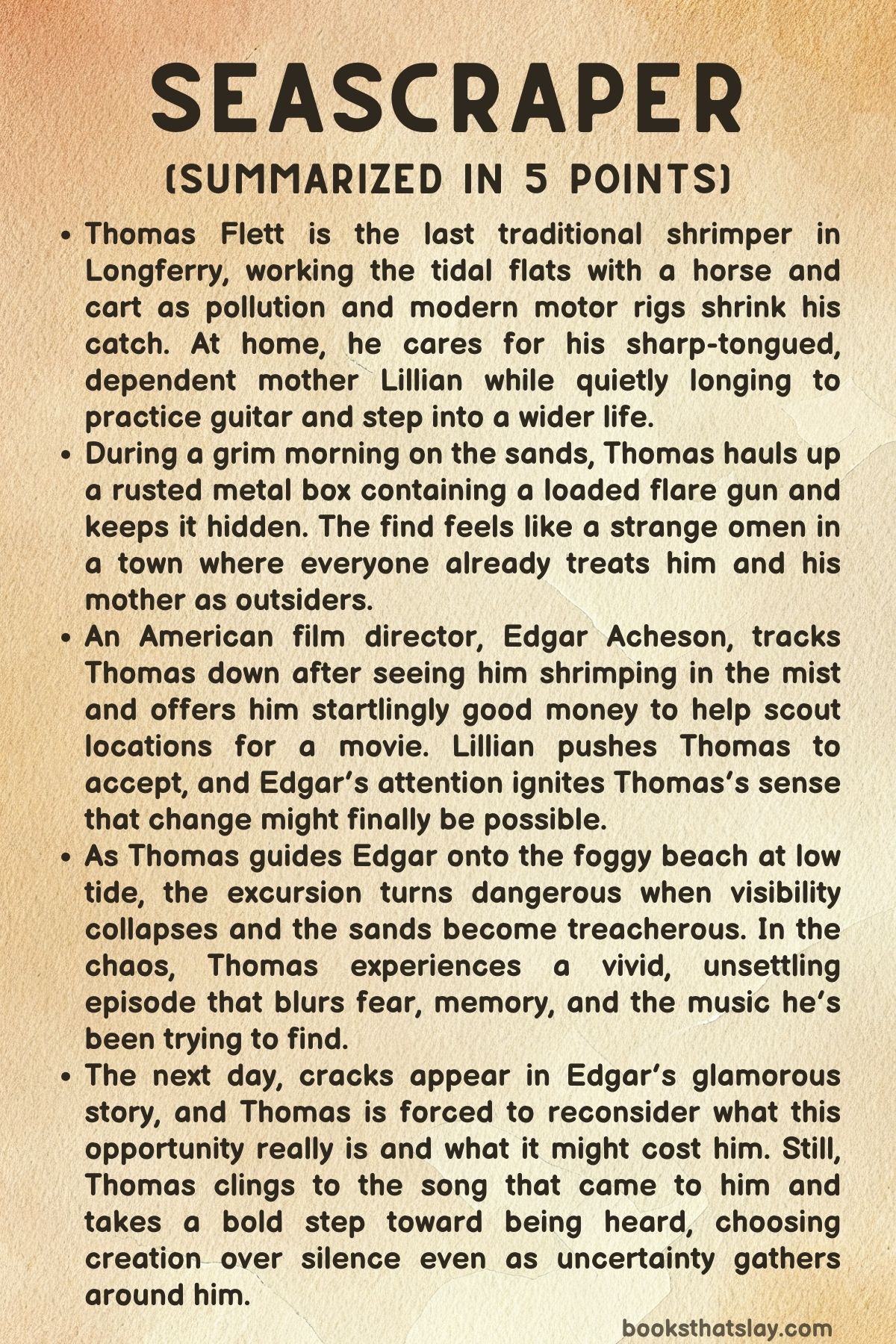

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood Summary, Characters and Themes

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood is a coastal coming-of-age story set in a town where old trades are fading and the shoreline itself feels unsafe. Thomas Flett is the last man still shrimping by horse and cart, stuck between duty to his sharp-tongued mother and a private hunger to make music.

When an American filmmaker arrives and singles Thomas out as something worth filming, a crack opens in Thomas’s narrow life. What follows is part working-class realism, part feverish night-mist confusion, as Thomas tries to work out what is true, what is performance, and what might finally belong to him.

Summary

Thomas Flett wakes before dawn in Longferry and prepares for another day of shrimping, a job that grows less viable each year. Motor rigs have replaced the old horse-and-cart method, and pollution has thinned the catch.

Thomas still keeps to the routine his grandfather taught him: patched clothes, tea in the kitchen, and quiet movements so he does not wake his mother, Lillian, until he must. Their life is close and tense at once.

Lillian depends on him, criticizes him, and seems to resent the limits they share. Thomas, in turn, feels bound to her, to the cottage, and to a town that looks past them.

He harnesses his heavy draught horse and heads down to the beach at low tide. The work is cold, wet, and punishing.

He sets the nets, pushes the cart into the shallows, and coaxes the horse through the water. The haul is small, and the wind and rain make the morning feel longer.

On one pass the horse balks, nervous in a way Thomas does not expect. When Thomas checks the net, he finds a rusted metal box tangled in the mesh.

Inside is a flare gun, still loaded. He considers throwing it back into the sea, then hides it under a tarpaulin instead, thinking it might be worth a few pounds or useful in trouble.

After finishing his trawl, Thomas sells the shrimp to a local merchant for a meagre payment and returns home through streets where neighbors barely acknowledge him. At the cottage he finds Lillian unexpectedly in the kitchen, and a stranger’s coat draped over a chair.

The visitor is Edgar Acheson, an American film director staying at the Metropole hotel. Edgar says he saw Thomas working on the shore and could not forget the sight of the horse, the cart, and the man alone in the mist.

He wants Thomas as a consultant and guide for a film he claims he is making, offering what sounds like an impossible sum for a few weeks’ work.

Edgar talks quickly and vividly, describing a story about an undertaker who takes the dead out to sea and encounters an island where the dead return. Lillian lights up at the attention and the money, pushing Thomas to accept.

Thomas is wary but tempted by the pay and the sudden chance to be seen as more than the town’s last shrumper. Edgar presses for an outing that very evening, wanting to scout the shoreline at low water.

When Thomas hesitates, Edgar raises the offer again, impatient to get what he wants. Thomas agrees, and later shows him a hand-drawn chart of dangerous sinkholes in the sand, knowledge passed down from shrimpers hinting at how quickly the beach can turn lethal.

They drive through drizzle to a derelict fogbell house that once helped guide fishermen. Edgar photographs it and talks about sets, storyboards, and how the place might serve his film.

On the ride back, he softens into something almost intimate, asking Thomas about his life and listening when Thomas admits he plays guitar and hopes, quietly, to perform at a local folk night. For Thomas, the conversation is like a door opening.

For Lillian, Edgar feels like rescue; she tells Thomas to keep the whole matter quiet.

Thomas rides into town to cash Edgar’s cheque and assumes the money will make everything real. At the post office he is served by Joan Wyeth, the sister of his friend Harry and the girl he has long admired from a distance.

Her calm friendliness unsettles him. When she mentions Harry’s club night and his guitar, Thomas panics at the thought of humiliating himself and asks her to tell Harry he cannot come.

He drifts afterward through shops, including a bookshop where he tries to find a book connected to Edgar’s film plans. He learns someone else has already asked for it, and he realizes Edgar is shaping Thomas’s world even when Edgar is not present.

That evening Thomas heads to meet Edgar by the war memorial, bringing the flare gun just in case. Edgar does not appear.

A hotel porter finds Thomas and tells him Edgar is delayed, suggesting Thomas wait at the Metropole for him. Thomas rides there with the porter perched awkwardly on the cart.

When Edgar finally arrives he is agitated, complaining about calls and money, and seems to bounce between charm and irritation. He gives Thomas a personal copy of a book by Mildred Ács, saying he could not find it in shops, and insists Thomas call him Edgar, as if they are already partners.

They go out across the sand into thickening fog. Edgar carries lanterns and a viewing device, speaking about shots and how the horse and cart might look as a moving image.

He sketches with charcoal and becomes excited by the scene as though the beach is already a set. Edgar asks Thomas to walk the horse into the water so he can judge the view.

Thomas does, then turns to find the lantern and Edgar’s voice gone. The fog swallows distance and sound.

Thomas calls out, bangs a bucket, and finally fires the flare. The gunshot cracks the air and the red light leaps upward.

The horse panics, the cart jerks, and Thomas is left trying to keep control while also searching for Edgar. He ties twine to the harness as a guide and walks out alone, following fading footprints and the faint shapes of disturbed sand.

Then the ground gives way beneath him. He drops into a hidden sinkpit, wedged and helpless as cold water creeps closer.

He cannot properly shout. He can only make broken sounds and wait.

A motor rig arrives, its engine and headlights appearing like an answer. A stocky woman pulls him free, locks him in the rig’s warm cabin, and drives him away from the beach.

Dazed and sick with seawater and fear, Thomas is proven vulnerable to suggestion, and his mind slips. He finds himself led to a lonely pub called The Fogbell, where music plays upstairs.

A bald guitarist seems to know Thomas intimately, speaks as though he has lived inside Thomas’s thoughts, and pushes him to play. Thomas performs on the man’s guitar with a confidence that feels borrowed.

The man calls himself Patrick Weir, claims to be Thomas’s father, and urges him to stay and take the stage name “Seascraper.” The encounter turns sour and frightening as Thomas begins choking and retching, and the promise collapses into rage.

Then Thomas is back on the beach. Edgar is there, real and close, hauling Thomas out with rope and practical technique he says he learned from films.

Edgar has found the horse by tracking the twine and the flare’s signal. Shaking, soaked, and coughing, Thomas helps guide the cart home through the fog.

Edgar offers showers and drinks and talks as if the night is simply material for tomorrow’s work. They agree to meet again at the next low tide, if Thomas is well enough.

At home Thomas tends the horse, lights a fire, drinks brandy, and becomes obsessed with the melody that haunted him during his hallucination. He works through the night telling himself he must not lose it, shaping it into a song and naming it “Seascraper.” By morning he is exhausted but certain he has made something real.

Lillian finds him on the floorboards, hungover and aching. She has already seen his guitar left out and his scribbled lyrics.

She mocks him, then misreads the song’s words as a wish for her death. Thomas tries to explain, and the argument opens into the family history Lillian has guarded.

She tells him about Patrick Weir: a teacher, an affair, and the violence of Thomas’s grandfather, who drove Patrick away and forbade Lillian from speaking his name. She insists Patrick never knew Thomas existed, and she believes Patrick had nothing to do with music.

If the song came from anywhere, she says, it came from Thomas.

Thomas rushes to the Metropole, late, and is sent to a hotel room where he meets Mildred Ács, Edgar’s elderly mother. Mildred is precise and unsentimental.

She says her role is to undo Edgar’s plans, and she begins packing his belongings as if this is a routine cleanup. She warns Thomas that Edgar takes liberties with people and leaves damage behind.

When Thomas defends Edgar for saving his life, Mildred dismisses the heroism as part of Edgar’s self-myth. She claims Edgar is addicted to Benzedrine, shows evidence of hidden pills, and says the grand film project is not what Edgar pretends.

Investors will not fund him; his promises do not hold; even the cheque to Thomas may not clear.

Thomas is shaken but refuses to take money from Mildred. He wants only to say goodbye and keep contact, clinging to the sense that Edgar’s arrival meant something.

Mildred leads him down, and Thomas sees Edgar at a window, sluggish and blocked by a retired policeman who seems to serve as handler confirmed by Mildred’s presence. Edgar waves and mimics filming with his hands, turning even this moment into a shot.

With Edgar’s car now a practical problem, Thomas decides to ask Harry Wyeth to drive it south. He goes to the Wyeths’ home, and Joan lets him in.

Thomas, awkward and excited, explains he has come into money through a film director and needs help. In the house he discovers Harry has bought a tape recorder.

On impulse, Thomas asks to use it. Alone with Joan’s attention, he records “Seascraper,” singing and playing better than he ever has.

When he finishes, Joan is stunned and sincere. She urges him to get it heard, as if naming the possibility makes it real.

After she leaves for work, Thomas kneels by the recorder, aware that the fragile evidence of his new self sits on a spool of tape that could be erased, lost, or kept, depending on what he does next.

Characters

Thomas Flett

Thomas Flett is a young man caught between duty and desire, living a life that is physically punishing and socially narrowing even before the sea itself begins to feel hostile. His shrimping routine—horse, cart, nets, low tide—defines him as someone stubbornly loyal to tradition, but that loyalty is not romantic; it is born from limited options, inherited expectations, and a quiet fear of stepping beyond what he knows.

He carries a private inner life that he barely permits himself to show: his guitar playing, his hopes of performing, his hunger to be seen as more than “the last shrimper.” The discovery of the flare gun is an early signal of how he thinks—practical, cautious, tempted by small chances to improve his situation, yet aware that survival in Longferry depends on discretion. As the story escalates, Thomas becomes the emotional center of the book’s tension between reality and imagination: the fog, the sinkpit, and the hallucinated encounter with his father blur the boundary between trauma and revelation.

Creating “Seascraper” becomes his first true act of authorship, a moment where he stops merely enduring his life and starts shaping it into art, and that shift changes the way he sees Longferry, his own future, and his right to want something beyond endurance.

Lillian Flett

Lillian is both Thomas’s anchor and his trap, a woman whose dependence is laced with sharpness, pride, and the bruised survival instincts of someone who has lived too long with scarcity. Her criticism can look like cruelty, but it often reads as fear—fear of humiliation, of poverty, of being abandoned again, and of her son growing beyond her.

She monitors Thomas’s movements, scolds him, and intrudes on his private aspirations, yet she also pushes him toward opportunity when it arrives, insisting he accept Edgar’s offer and treating the visit as a rare crack in their closed world. Some of her most unsettling power comes from intimacy that is not comforting: the moment she asks Thomas to press her back shows how blurred their boundaries have become, how care has turned into a kind of possession.

Her revelations about Patrick Weir complicate her further; she is not simply a bitter mother, but someone shaped by coercion, secrecy, and the authority of Thomas’s grandfather. When she mocks the song and misreads its lyrics as a wish to bury her, it exposes her deepest vulnerability: she experiences Thomas’s growth as a threat to her safety.

Lillian’s tragedy is that she recognizes what music could mean for Thomas, yet she cannot allow herself to believe in it as a lifeline, because her life has taught her that hope is usually punished.

Edgar Acheson

Edgar Acheson arrives like a storm front—glamorous, intense, persuasive, and slightly unreal against Longferry’s grey routines—and he functions as both catalyst and cautionary tale. To Thomas, Edgar represents escape: money, attention, artistry, and the intoxicating idea that an outsider might validate the worth of Thomas’s disappearing world.

Edgar’s charisma is genuine, but so are his manipulations: he presses for access, escalates offers to override hesitation, and treats Thomas’s life as raw material for his own vision. Even his warmth has a kind of acquisitive quality, as though people and places are valuable primarily when they can be framed, photographed, storyboarded, and turned into story.

The fog sequence reveals how Edgar’s creativity can become dangerous when paired with impulsiveness, and later Mildred’s intervention reframes his behavior as part inspiration, part self-destruction. Edgar’s relationship to truth is unstable; he may believe in his projects, but belief does not equal viability, and the possibility that his cheque will bounce turns his grand promises into emotional risk for anyone who trusts him.

Yet he is not merely a villain: he does save Thomas at the sinkpit, he shows real talent in his drawings, and he carries a wounded yearning—especially around his daughter—that suggests he uses art as a substitute for intimacy he cannot sustain. In Seascraper, Edgar embodies the seductive danger of being “chosen” by someone powerful: the attention can awaken you, but it can also consume you.

Joan Wyeth

Joan Wyeth is the story’s quiet counterweight to spectacle, offering Thomas something Edgar cannot: steady recognition without glamour or coercion. Her calm friendliness at the post office lands with disproportionate force because it interrupts Thomas’s habitual shame; she sees him in an ordinary setting and treats him as worthy of normal warmth, which is rare in his social world.

Joan’s presence also intensifies Thomas’s self-consciousness—he becomes clumsy, evasive, and fearful of embarrassment—showing how deeply he expects rejection or ridicule. What makes her especially important is how she responds to his music: she does not merely flatter him; she listens, is genuinely stunned, and urges him toward being heard.

That reaction becomes proof, for Thomas, that the song is real and that he is capable. Joan’s intelligence and curiosity show in the way she handles the book and poetry, suggesting a life of thought and feeling that extends beyond Longferry’s small judgments.

She also introduces a form of intimacy that is hopeful rather than suffocating: she opens a door without demanding possession. If Thomas’s mother represents love as enclosure, Joan represents love as possibility.

Harry Wyeth

Harry Wyeth exists at the hinge point between Thomas’s isolation and the small community of music that could pull him outward. He is associated with the folk club night and the social world Thomas longs for but avoids, and even when he is offstage in much of the summary, his influence is structural: he is the reason Joan knows about Thomas’s playing, the reason there is a tape recorder available, and the reason Thomas has a plausible ally for the trip south with Edgar’s car.

Harry’s recorder is more than a prop; it symbolizes preservation and risk—the ability to capture a voice, and the fear that the captured thing can be erased. Harry’s casual ownership of musical tools and spaces highlights Thomas’s sense of being an outsider even in the world he desires.

At the same time, Harry’s existence suggests that performance is not an impossible fantasy in Longferry; it is happening, nearby, and Thomas is closer to it than his fear admits.

John Rigby

John Rigby, the local fish merchant, represents the economic reality pressing down on Thomas’s life: the work is hard, the pay is small, and tradition has little bargaining power in a modernizing system. His two-pound payment is not just a detail of trade; it is a measure of Thomas’s confinement, showing how much labor is converted into how little freedom.

Rigby’s role is transactional, but that is precisely why he matters—he is the human face of a local economy that no longer rewards the kind of work Thomas does, reinforcing the sense that Thomas is living at the end of something.

Patrick Weir

Patrick Weir is the most emotionally charged absence in Thomas’s life, and his appearance—whether supernatural, psychological, or a trauma-shaped hallucination—crystallizes Thomas’s hunger for origin and instruction. In the vision, Patrick is both intimate and invasive: he claims to have been the voice in Thomas’s head, speaks as if he knows Thomas’s secrets, and offers a seductive narrative in which Thomas’s talent is inherited, destined, and ready to be named.

The offer to perform under the name “Seascraper” turns Patrick into a mythmaker, someone who tries to re-author Thomas’s identity in a single dramatic gesture. But the encounter curdles quickly, shifting from welcome to anger, and that volatility matters: it suggests that even imagined fathers can reproduce the danger of male authority and disappointment.

Later, Lillian’s account punctures the myth—Patrick never knew Thomas existed and had no link to music—reframing the vision as Thomas’s mind manufacturing a father-shaped container for his own emerging creativity. Patrick’s role, then, is paradoxical: he is a lie that helps Thomas reach a truth, a phantom permission slip that allows Thomas to claim his own song.

Mildred Ács

Mildred Ács enters as an elegant, controlled presence whose purpose is to dismantle Edgar’s fantasy and protect others from its collateral damage. She is authoritative in a way Thomas is not used to encountering: she doesn’t charm or negotiate; she states, diagnoses, and moves to end the situation.

Her relationship to Edgar is complex because she is not merely a scolding parent—she is also implicated in his artistic identity, given that her out-of-print work sits at the center of his obsession. Mildred’s harshness can read as cruelty, but it carries the exhaustion of someone who has spent years managing a talented, destructive person, cleaning up after projects and incidents, and watching admiration repeatedly turn into harm.

By exposing Edgar’s Benzedrine addiction and his pattern of unfinished ventures, she reframes the earlier magnetism as symptom as well as style. Importantly, she tests Thomas—lying about Edgar’s whereabouts to gauge Thomas’s intentions—suggesting she is both protective and strategic.

Yet she is not entirely closed: she gives Thomas her address, offers practical solutions, and urges him to keep the damaged book rather than shame him for it. Mildred represents realism without tenderness, a necessary corrective to Edgar’s intoxication and to Thomas’s temptation to believe that being “chosen” automatically means being saved.

Stephen

Stephen, the retired policeman accompanying Mildred, reinforces the sense of containment and control around Edgar at the Metropole. He is a quiet embodiment of enforcement: not overtly violent, but clearly positioned to prevent chaos, manage Edgar, and limit access.

When Edgar tries to open the window and Stephen stops him, Stephen becomes the physical boundary between Edgar’s impulsive theatrics and the consequences others have learned to anticipate. His presence also highlights how far Edgar has fallen socially—once a director commanding sets, now a man supervised like a risk.

Themes

Disappearing Work and the Pressure of Modern Change

Thomas’s morning routine is built around a trade that is visibly running out of space in the world. Shrimping by horse and cart depends on tides, endurance, and a kind of local knowledge that cannot be rushed, yet everything around him rewards speed and scale instead.

Motor rigs do the same job faster, and the economics of the town quietly confirm that tradition is no longer a virtue on its own. The two pounds he earns for a morning’s labour makes his work feel less like a livelihood and more like a stubborn holdout, and the loneliness of being the last shrimper turns his job into a public reminder of what Longferry has stopped valuing.

Even the horse, inherited and unnamed, reads like a living tool from a previous era—loyal, patient, and vulnerable to panic when the conditions change. Modernity arrives not only as machinery but also as a new kind of attention: Edgar’s sudden interest frames Thomas’s labour as a visual spectacle, something rare enough to be filmed, packaged, and sold as atmosphere.

That shift is unsettling because it suggests Thomas’s work matters most when it becomes someone else’s raw material. The town’s social cues reinforce the same drift: neighbours barely acknowledge the Fletts, local commerce is limited, and Thomas’s sense of pride has to fight against the implication that his life is already obsolete.

What makes this theme sting is that the decline is not dramatic; it is administrative, gradual, and socially endorsed. Thomas can feel possibility in Edgar’s offer and in his own music, but that hope is born from the same pressure: if the old work won’t sustain him, he must either become a relic or reinvent himself, even if reinvention risks losing the only identity he has been allowed to inhabit.

A Polluted Sea and the Erosion of Safety

The sea in Longferry is not a neutral backdrop; it is a damaged force that shapes the body and the mind. Chemicals and sewage reduce the catch, but they also change what the water represents.

Instead of abundance or continuity, the shoreline becomes a warning system: cold, contaminated, and unpredictable. Thomas works in it anyway, because he has to, and that necessity creates a harsh intimacy with harm.

The hidden sinkpits are the clearest example of how danger has become normal. The beach looks open and simple, yet it contains traps that swallow a person without spectacle, and Thomas carries a hand-drawn chart the way another worker might carry protective gear.

That chart is knowledge passed down, but it also exposes how survival depends on staying alert to threats that the wider world either ignores or finds convenient. The flare gun he pulls from the nets strengthens this atmosphere.

It is an object meant for rescue, yet it arrives as rusted contraband, something half-buried and still loaded, suggesting that even “help” in this place is compromised. When Thomas fires the flare, it does not cleanly save him; it terrifies the horse, disrupts orientation, and adds chaos to an already unsafe environment.

The fog amplifies that instability, turning familiar ground into a shifting hazard where sound misleads and distance becomes impossible to judge. The later coughing and retching, the seawater in his body, and the hungover ache on his floorboards extend the sea’s reach into his home life, as if the coastline follows him indoors.

This theme also carries a moral weight: pollution and neglect do not only foul water; they corrode trust in the future. A community that allows its sea to become contaminated is also a community that quietly accepts smaller horizons for people like Thomas.

The physical decay of the coast becomes a social decay, where danger is managed privately rather than solved collectively, and where survival is treated as an individual problem instead of a shared responsibility.

Care, Control, and the Trap of Family Duty

Thomas and Lillian’s relationship runs on constant service, but the emotional price is high because care in their household is tangled with control. Thomas cooks tea, supports her routines, tends to her needs, and absorbs her moods, yet the labour is never purely affectionate; it is also a form of confinement.

Lillian’s criticism and dependence keep him close, and even when she praises him, the approval feels conditional, as if his worth must be continually proven through obedience. The intimacy of the back-pain scene makes this dynamic impossible to romanticize.

Thomas’s discomfort is not only about the physical closeness; it is about how easily his body becomes an extension of her demands, how quickly personal boundaries are rewritten as obligations. Her insistence that he accept Edgar’s offer shows another side of the same pattern: she frames opportunity as something he owes her, not something he chooses for himself.

She also warns him to tell no one, turning good fortune into a secret that strengthens her role as gatekeeper. Even Thomas’s music becomes contested territory.

He hides his guitar like contraband, practicing quietly in the stable, and when Lillian discovers the lyrics, she reads them through a lens of abandonment and grievance, accusing him of wanting her buried. Her reaction reveals how threatened she feels by any sign of his independence.

The revelation about Patrick Weir intensifies this theme by showing that family duty has been shaped by older violence and fear. Lillian’s silence was enforced by Thomas’s grandfather, and the household’s current tension is partly the aftershock of that domination.

Her warning that music won’t feed them is practical, but it is also a way to keep Thomas anchored to necessity and guilt. In Seascraper, family duty is not presented as simple loyalty; it is a system that can protect and suffocate at the same time, leaving Thomas struggling to separate love from obligation, and care from captivity.

Art, Performance, and the Risk of Being Used

Edgar’s arrival introduces art as both escape and threat. He speaks with charm and intensity, turning Longferry into a potential film set and Thomas into a valuable “local” who can lend authenticity.

The offer of one hundred pounds, then double, is life-changing in Thomas’s world, but it is also a negotiation where Edgar’s urgency and persuasion override Thomas’s initial boundaries. Edgar’s attention flatters Lillian, excites Thomas, and reframes shrimping as a cinematic image, yet the same framing strips Thomas’s work of its private dignity.

It becomes content, not life. The hotel scene adds another layer: Thomas waits in the lobby like an outsider, promised a brandy that never arrives, learning in real time how the world of money and reputation treats people who don’t belong to it.

Edgar’s agitation, his complaints about calls and tips, and his inhaler use show a man who performs competence while barely holding himself together. Mildred’s later intervention sharpens the danger: she describes Edgar as talented but destructive, someone who “takes liberties,” harms people, and builds grand plans that collapse.

Whether every detail she gives is fully reliable or partly motivated by protective control, the effect on Thomas is the same: the artistic world he glimpsed is unstable, exploitative, and powered by obsession. Even the book Edgar gifts him carries this ambivalence.

It is a gesture of intimacy, but also a way Edgar plants his own story into Thomas’s hands, pulling him deeper into the director’s orbit. Against this, Thomas’s music becomes a counter-form of art—one that he creates from lived experience rather than borrowing others for mood.

Yet music also demands performance, exposure, and judgement. The folk club, the pressure to play, the tape recorder, and Joan’s reaction all show that artistic expression can quickly turn into a public test.

Seascraper treats art as a doorway to a larger life while warning that doors can swing both ways: they can free someone from a shrinking world, or pull them into a new system where charisma, money, and narrative control belong to someone else.

Voice, Self-Authorship, and the Fight to Claim a Life

Thomas’s deepest shift happens when he begins to treat his own inner life as real and worthy of being heard. Before the song, his days are defined by repetition and by roles assigned to him: dutiful son, last shrimper, quiet neighbour, shy admirer.

His guitar playing exists only in hidden pockets of time, as if his desire to make music is something he must apologize for. The night on the beach breaks that pattern.

The hallucination (or dream) in which Patrick Weir appears is significant not simply because it is strange, but because it externalizes Thomas’s hunger for permission. The imagined father figure offers recognition, a name, a stage identity, and a future; in other words, he voices what Thomas cannot yet claim on his own.

When that vision collapses and Thomas returns to the beach, the loss forces him to confront a harder truth: if he wants a voice, he has to build it without magical validation. The act of waking before dawn and shaping the melody into a complete song is a form of self-authorship.

He turns the physical facts of his life—tides, the cart, the cold, the risk of burial in water—into language and structure that he controls. Lillian’s mocking “Mozart” comment and her misreading of the lyrics are painful precisely because they attempt to take that control away, reducing his work to a joke or a threat.

Her later insistence that Patrick never cared about music, and that the song must be Thomas’s, ironically pushes him toward ownership, even if she intends it as a warning. The recording scene with Joan makes the theme concrete.

A tape recorder does not care about class or shyness; it captures what happens. Thomas’s fear of rewinding and erasing the tape mirrors a larger fear that his emerging self could vanish if he treats it as temporary.

Joan’s stunned praise matters because it is specific and immediate; it suggests his voice can move someone outside his own head. In Seascraper, finding a voice is not a decorative subplot.

It is a survival strategy, a way Thomas begins to choose a narrative for himself rather than letting poverty, family duty, and community indifference decide what he is allowed to be.

Fog, Uncertainty, and the Return of Buried History

The fog on the beach is more than weather; it functions like a psychological condition where the past, the body, and perception lose their usual boundaries. In that whitened space, Edgar’s lantern can disappear within seconds, footprints fade, and the difference between “I am safe” and “I am trapped” becomes a single step.

This instability sets the stage for Thomas’s hallucinatory encounter with Patrick Weir. Whether the experience is a stress response, a near-drowning delirium, or something more ambiguous, its content is shaped by what has been suppressed in his life.

The father he never knew arrives as a voice that claims to have been inside his head, which aligns with how absence can still guide a person: through questions left unanswered, through inherited shame, and through the constant need to imagine what was denied. The later conversation with Lillian confirms that Thomas’s family story has been controlled through secrecy and intimidation.

His grandfather’s violence toward Patrick, the threat of losing home and child, and the long silence about Thomas’s origins show how history in this family was not simply forgotten; it was actively buried. The beach’s sinkpits become an external version of that burial: hidden hollows that swallow what walks over them, leaving little trace.

Even Edgar’s situation mirrors this theme. Mildred describes a career that peaked and then deteriorated, marked by addiction, unfinished projects, and reputational damage.

The director’s frantic confidence and his performative devotion to his daughter read like a man hiding from his own decline. The uncertainty of whether the cheque will bounce, whether the film is real, and whether Edgar’s attention is sincere creates a world where promises cannot be taken at face value.

Thomas is forced to operate without reliable footing—financially, emotionally, even literally on the sand. Yet the theme is not only about confusion; it is also about what returns when suppression fails.

A name like “Seascraper” comes up from a hallucination and becomes a title he chooses. A father’s story, kept secret for decades, surfaces in Lillian’s account.

The town that felt small begins to feel reachable once Thomas has created something that did not exist before. Seascraper shows how uncertainty can be frightening, but it can also break the seal on inherited silence, making space for truths that were kept out of sight and for identities that were never allowed to fully form.