Seduction Theory Summary, Characters and Themes | Emily Adrian

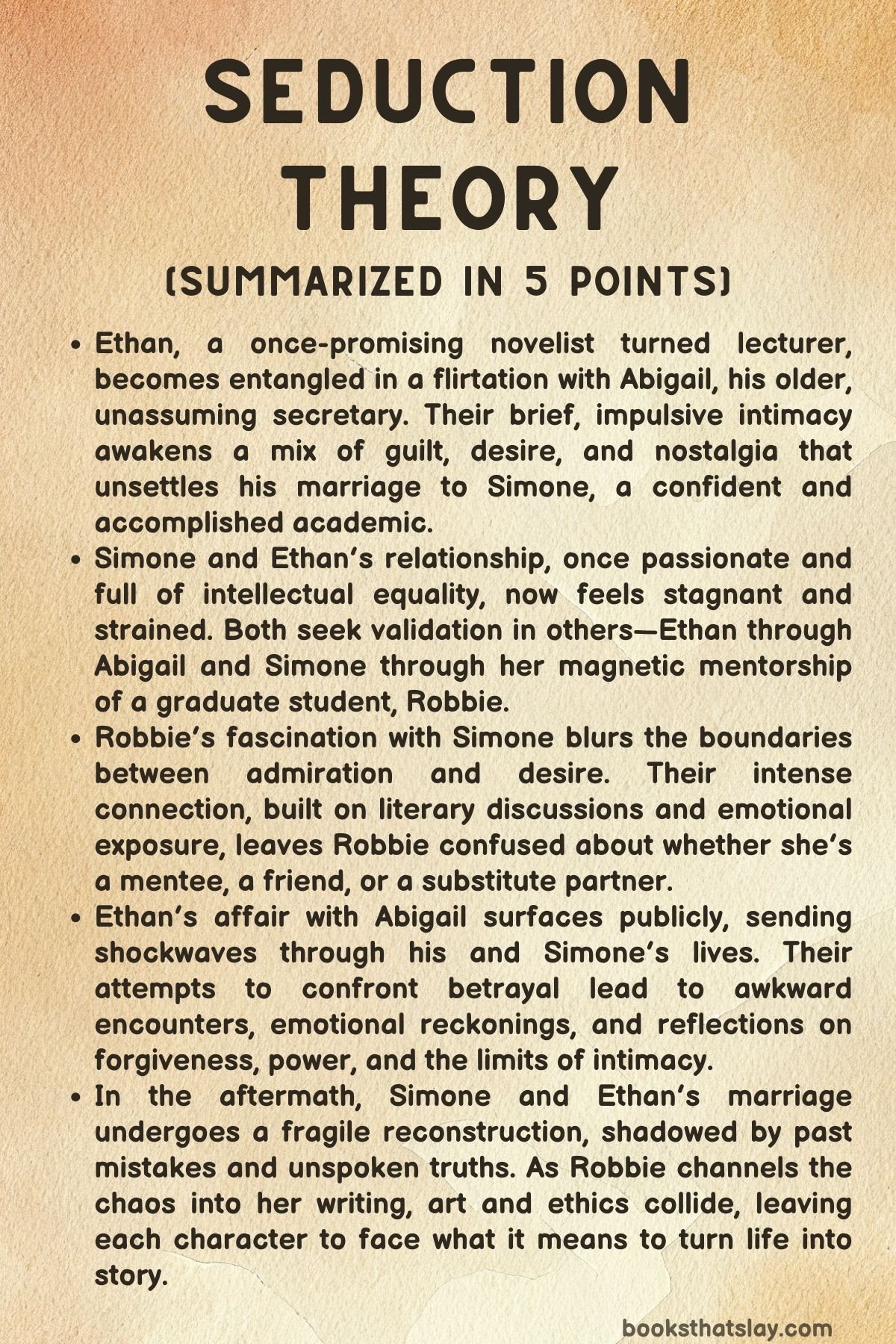

Seduction Theory by Emily Adrian is a sharp and layered exploration of desire, power, and the shifting boundaries of intimacy within academic and creative circles. The novel follows Ethan, a once-promising novelist turned writing lecturer, and his wife Simone, a celebrated professor, as their marriage unravels through infidelity and moral ambiguity.

When Ethan’s affair with his secretary Abigail collides with Simone’s emotionally charged mentorship of a student, both are forced to confront the ethics of seduction—romantic, intellectual, and artistic. Adrian crafts a psychologically astute portrayal of human weakness, examining how people seek connection while blurring the lines between love, mentorship, and manipulation.

Summary

Ethan, a lecturer and former novelist, attends a creative writing department party where he finds himself unexpectedly drawn to Abigail, his self-proclaimed “secretary. ” She’s plain, older, and unassuming, yet her candor and vulnerability captivate him.

What begins as flirtation over drinks turns into charged intimacy when she feeds him kale salad and confesses her moral flaws. Ethan is both thrilled and unsettled, sensing the danger in their chemistry.

Outside, their conversation feels almost like courtship, and when they help retrieve a colleague’s lost dog together, Ethan basks in her admiration. Back home, he lies beside his wife, Simone, longing for emotional connection but finding only distance.

Simone, a brilliant and confident professor, embodies everything Abigail is not. Their marriage, once rooted in shared ambition and affection, now feels like an intellectual partnership devoid of tenderness.

Ethan craves validation but receives only Simone’s distracted sympathy. The next morning, during a jog, the couple encounters Abigail, igniting Ethan’s panic over potential exposure.

Later, he admits to Simone that he’s “becoming friends” with Abigail. Instead of jealousy, Simone offers approval, viewing female friendship as a way for men to access emotional depth.

She even recalls a disturbing encounter with a colleague, claiming true friendship requires such uncomfortable honesty. Ethan feels queasy at her openness but hides his discomfort.

Their conversation turns toward independence. Simone reveals she might skip their annual Oregon trip to focus on her research and training.

Ethan, once terrified of being apart from her, finds himself exhilarated by the thought of distance. For him, it represents the illusion of freedom—a small rebellion against their stifling intellectual marriage.

When Ethan visits Oregon to see his mother, he reflects on his youth, lost ambition, and past boundary-crossing with students. He recalls Adele, a former student who once confessed her love to him, and how close he came to misconduct.

That memory haunts him, especially as he compares his earlier restraint to his growing attraction to Abigail. Meanwhile, Simone begins mentoring a graduate student, Robbie, who narrates part of the story.

Robbie idolizes Simone, drawn to her intelligence and beauty. Their mentorship quickly turns into an intense, unbalanced friendship.

Simone invites Robbie into her home, recording their conversations for “research,” encouraging her to shower there, and giving her clothes. Their connection becomes emotionally consuming—Simone oscillates between affection and control, keeping Robbie in constant uncertainty.

When Simone eventually ends the relationship just before Ethan’s return, Robbie feels discarded and exploited. The episode ends with Simone sending Robbie a recording of their runs, in which Simone concludes that mentorship and seduction are indistinguishable.

Ethan, back home, pretends normalcy while secretly covering his affair with Abigail. But guilt festers.

When Abigail calls for help with her son, Byron, Ethan agrees, convincing himself it’s harmless. His visit reveals Abigail’s instability—her exhaustion as a mother and her strange methods of discipline.

Ethan’s pity merges with desire, and though he tries to end things, Abigail interprets his restraint as affection. A brief kiss exposes his nut allergy, and he flees in panic and shame.

At a department celebration, all threads collide. Ethan’s success as a writer temporarily revives his bond with Simone, but Abigail and Robbie are both present, each carrying secrets.

Drunken, competitive, and charged with tension, the evening spirals. Ethan and Simone sneak away to have sex upstairs, only for Abigail to walk in on them.

Humiliated, she exposes their affair via email the next morning, copying Simone.

Ethan’s confession devastates Simone, who remembers her own near-infidelity with Abigail’s ex, Victor. For her, Ethan’s betrayal shatters the one person she trusted entirely.

Their ensuing confrontation swings between rage and intimacy. Unable to bear the wreckage, they embark on a spontaneous road trip westward.

The journey becomes a test of endurance—Simone probes Ethan’s motives, mocks his excuses, and alternates between forgiving him and rejecting him. Along the way, they meet Adele and her husband, Spencer, a therapist who invites them to dinner.

Spencer psychoanalyzes their situation, while Adele treats their past flirtation with nonchalance. Simone, humiliated yet fascinated, briefly considers cheating on Ethan for revenge but resists.

She realizes forgiveness and vengeance share the same root—a need to regain control.

Later, Simone decides to confront her pain head-on by visiting Abigail’s family home. Ethan, terrified, pleads with her not to go, but she insists.

At the barbecue, Simone maintains composure, even showing grace toward Abigail. Their conversation culminates in a strange alliance: Abigail admits the sex with Ethan “wasn’t even good,” and Simone feels oddly comforted.

In Oregon, Simone and Ethan begin to rebuild. The setting, full of domestic routines and family warmth, contrasts with their emotional exhaustion.

Their reconnection feels both fragile and real. During a beach trip, Simone reflects that their marriage will always carry imperfection, yet she chooses to stay.

She recalls advice from her old mentor, who once said a woman must always do what she wants. In that moment, Simone decides she still wants Ethan, not out of forgiveness, but choice.

The perspective shifts again to Robbie, who now dates another woman, Maggie, while wrestling with creative ambition. Simone abruptly ends their mentorship, declaring she’s reestablishing ethical boundaries.

Robbie channels her heartbreak into fiction, writing a thinly veiled novel based on Simone, Ethan, and Abigail. Despite Simone’s warnings, Robbie persists.

Her thesis becomes a scandalous masterpiece, a reflection of all their entanglements.

At Robbie’s thesis defense, all the players—Ethan, Simone, Abigail, and the department chair—assemble. The air is thick with unspoken history.

Robbie imagines scenes of chaos—Simone confessing, Ethan unraveling—but reality remains composed. Simone praises Robbie’s work publicly, calling it brilliant, yet her written feedback ends with a cutting line: “Less is more.

Afterward, Robbie receives Ethan’s agent’s contact information, recognizing that her success is both victory and closure. Meanwhile, Ethan and Simone’s renewed stability, symbolized by a bowl of figs in his office, suggests that their relationship has survived—wounded, altered, but intact.

Seduction Theory closes as an examination of desire’s moral gray zones—how love, mentorship, and ambition often operate under the same manipulative logic. Through its rotating perspectives, the novel leaves readers questioning whether intimacy can ever exist without power, or if every act of connection carries its own quiet seduction.

Characters

Ethan

Ethan stands at the center of Seduction Theory, embodying the contradictions of a man torn between moral awareness and self-indulgence. Once a promising novelist, now a weary academic, Ethan’s life is marked by inertia and insecurity.

His affair with Abigail is not driven by lust alone but by a craving for validation and a reprieve from the emotional distance he feels in his marriage. He intellectualizes his guilt, often mistaking his own self-absorption for introspection.

Ethan’s interactions with women—Simone, Abigail, Adele, and later Robbie—reveal a pattern of blurred boundaries masked as curiosity or mentorship. He mistakes emotional dependence for affection and attention for love.

Despite moments of genuine remorse, he rarely changes, preferring to rationalize his flaws as by-products of artistic temperament. His moral decline is subtle, wrapped in charm and intellect, and by the novel’s end, he remains both pitiable and culpable—a man aware of his failures yet unwilling to fully confront them.

Simone

Simone, Ethan’s wife, is the intellectual and emotional core of Seduction Theory, a woman whose poise conceals deep vulnerability. Tenured, brilliant, and admired, she has built a life of control and academic authority, yet her internal world trembles beneath the weight of loss, betrayal, and suppressed desire.

Simone’s entanglement with her student, Robbie, mirrors Ethan’s moral lapses, revealing that she too seeks power, intimacy, and validation outside the conventional bounds of marriage. Her manipulation of Robbie—alternating warmth and coldness—reflects her need to dominate the emotional realm she cannot control in her partnership with Ethan.

Yet Simone’s intelligence makes her self-aware; she sees her cruelty and still cannot stop it. After Ethan’s affair, Simone’s breakdown is as much about shattered trust as it is about wounded pride.

She oscillates between vengeance and forgiveness, finally choosing a fragile reconciliation not out of naivety but acceptance of imperfection. By the end, Simone becomes a portrait of complexity: a woman capable of both exploitation and compassion, intellect and surrender.

Abigail

Abigail functions as both catalyst and mirror in Seduction Theory, exposing the hypocrisies of the academic elite. Older, plain, and emotionally unguarded, she represents a kind of raw authenticity that contrasts sharply with Simone’s polish and Ethan’s cynicism.

Her flirtation with Ethan is clumsy yet sincere, born from loneliness rather than manipulation. However, her vulnerability turns volatile—her act of copying Simone on the email that exposes the affair is both revenge and self-assertion.

Abigail’s moral compass is inconsistent; she can be cruelly honest and self-deceiving at once. Her relationship with her son Byron hints at a darker instability, a blend of maternal devotion and frustration.

Through Abigail, the novel examines class and emotional hierarchies: she is the outsider in a world of intellectual pretense, punished for transgressions that her academic counterparts disguise as “research” or “friendship. ” In the end, Abigail’s power lies in her disruption—she destabilizes everyone around her and forces the façade of moral superiority to collapse.

Robbie

Robbie, Simone’s graduate student, is both victim and inheritor of the emotional manipulations that pervade Seduction Theory. Her youthful admiration for Simone transforms into obsession, and her mentorship becomes a psychological seduction.

Robbie’s voice, alternating between awe and resentment, reveals how power operates in academic intimacy. She is perceptive enough to see Simone’s control but too enthralled to resist it.

Later, Robbie’s decision to fictionalize the lives of Simone, Ethan, and Abigail in her thesis becomes both rebellion and revenge—an assertion of agency through art. By transforming personal trauma into narrative, she claims ownership of the story that once consumed her.

Yet, Robbie’s triumph is ambiguous: though she earns recognition and approval, she also perpetuates the same cycle of exploitation she once suffered. Her relationship with Simone reflects the novel’s central thesis—that mentorship and seduction are not opposites but entwined acts of influence and power.

Lois

Lois, Ethan’s mother, serves as a quiet moral counterpoint to the chaos surrounding her son. Her presence in Seduction Theory grounds the narrative in generational continuity and emotional endurance.

Though peripheral to the central conflicts, Lois’s kindness and domestic steadiness expose Ethan’s immaturity. In her home, he briefly regains a sense of innocence and belonging, moments that highlight how far he has strayed from genuine connection.

Lois does not judge or intervene directly, but her quiet decency becomes an implicit critique of the intellectual and emotional corruption of the others. Through her, Emily Adrian contrasts lived experience with theoretical understanding—showing that wisdom and empathy often reside outside academia’s self-conscious moral debates.

Byron

Byron, Abigail’s young son, symbolizes the unfiltered consequences of adult dysfunction in Seduction Theory. His erratic behavior—his fascination with death, his tantrums, his dependence on his mother’s unstable affection—mirrors the emotional chaos of the adults around him.

Byron’s innocence is repeatedly interrupted by glimpses of cruelty and confusion, making him a haunting reflection of the story’s moral decay. When Abigail admits to hanging him upside down to stop his fits, the image becomes a metaphor for the novel’s emotional inversion—where care and harm, love and control, constantly blur.

Byron’s presence reminds readers that seduction, in all its forms, does not only consume the consenting adults but leaves its mark on the next generation.

Adele

Adele, once Ethan’s student and now a successful novelist, represents both the consequences of Ethan’s past indiscretions and the cyclical nature of exploitation within creative communities. Her youthful infatuation with Ethan parallels Robbie’s with Simone, suggesting that seduction and mentorship are recurring, learned behaviors within academia.

When Adele reappears later in the novel—married to a therapist and seemingly thriving—she exposes the self-serving narratives that Ethan and Simone have built around their guilt. Her nonchalance about her past flirtations and her professional success force Simone and Ethan to confront their own stagnation.

Adele’s composure and independence make her one of the few characters who escapes the web of manipulation unscathed, turning her earlier vulnerability into a form of quiet triumph.

Spencer Shane

Spencer Shane, Adele’s husband and a therapist, enters Seduction Theory as an observer and subtle provocateur. His calm demeanor and analytical insight mask a latent opportunism—he uses others’ vulnerabilities as fodder for understanding and control.

His encounter with Simone, in which he invites her to “stay tonight,” blurs the boundary between empathy and temptation, echoing the novel’s theme that emotional intimacy often doubles as manipulation. Spencer’s interactions expose the limits of therapy and intellectualization as means of redemption.

He serves as a mirror to Ethan: both men use language to rationalize desire, but where Ethan hides behind guilt, Spencer disguises predation as understanding. Through him, the novel closes the circle of moral ambiguity, showing that seduction is not confined to romance or mentorship but permeates every human attempt at connection.

Themes

Power and Desire

Throughout Seduction Theory, power and desire exist in a fraught, reciprocal relationship where intimacy becomes a form of manipulation. Emily Adrian constructs her characters around the subtle and often dangerous ways in which authority and attraction intersect, particularly in academic and mentorship settings.

Ethan’s interactions with Abigail, Adele, and even his students reveal how professional boundaries dissolve under emotional need and narcissistic validation. His initial flirtation with Abigail is less about physical attraction than about regaining a sense of vitality and control after years of creative stagnation.

Similarly, Simone’s bond with her student Robbie mirrors Ethan’s dynamic with Abigail but under a different guise—her dominance is intellectual, her seduction rooted in admiration and mentorship. The language of education becomes the language of seduction, where teaching and desire are indistinguishable.

Both Ethan and Simone exploit emotional vulnerability to affirm their relevance and authority. Yet the novel never simplifies their actions into pure predation; it portrays power and desire as mutually sustaining forces that expose the fragility of adult morality.

In the world of the novel, desire does not liberate but entangles, and those who seek validation through it inevitably find themselves trapped in cycles of guilt, longing, and self-justification. The title itself becomes a commentary on how “theory” rationalizes impulses that are ultimately emotional and destructive.

Marriage and Betrayal

Marriage in Seduction Theory functions as both refuge and battlefield, a site where love and resentment coexist in uneasy balance. Ethan and Simone’s marriage, once defined by idealism and shared intellect, has eroded into a quiet performance of connection.

Their early vow not to “bore or betray” each other becomes tragically ironic, as both commit forms of betrayal—Ethan’s physical infidelity with Abigail and Simone’s emotional entanglement with Robbie. Yet Adrian portrays their betrayals not as acts of cruelty but as desperate attempts to reclaim vitality and identity.

The tension between forgiveness and punishment drives their interactions after the affair is exposed. Simone’s oscillation between fury and tenderness captures the complexity of long-term intimacy: she cannot simply leave because the marriage still contains remnants of genuine love.

Ethan’s guilt, meanwhile, is shaped less by moral awareness than by fear of losing Simone’s admiration. The novel refuses to offer redemption or closure; instead, it presents marriage as a process of continual negotiation between independence and interdependence, desire and decay.

In the end, their physical reconnection in Oregon signals not reconciliation but acceptance of imperfection. The marriage survives not because it is pure, but because both partners acknowledge that imperfection is the only truth love can sustain.

Gender, Power, and the Academic World

The academic setting in Seduction Theory provides a microcosm for examining gendered hierarchies and the illusion of intellectual equality. The creative writing department is portrayed as a space where mentorship blurs into seduction, and where admiration is often mistaken for love.

Female success, embodied in Simone, carries its own burdens—she must constantly perform brilliance while negotiating male insecurity and the threat of professional scandal. Ethan’s masculinity, once bolstered by his literary reputation, deteriorates as he becomes overshadowed by Simone’s achievements.

His infidelity is partly a rebellion against the emasculation he feels within academia’s meritocratic structure. Simone, on the other hand, exerts power through intellectual and emotional dominance, but her relationship with Robbie reveals how easily mentorship can replicate patriarchal patterns of exploitation.

Adrian’s depiction of the university exposes the hypocrisy of institutions that claim moral enlightenment while fostering environments ripe for ethical breaches. Power dynamics are never static; they shift according to gender, ambition, and vulnerability.

The academic world becomes a stage where desire masquerades as discourse, and every relationship is shadowed by questions of consent, reputation, and control.

The Search for Identity and Validation

Ethan and Simone’s journeys throughout Seduction Theory reflect a shared hunger for validation that extends beyond sexual or professional success. Ethan’s fading literary career and Simone’s intellectual prominence create an imbalance that neither can reconcile.

Both characters seek recognition not only from each other but from external figures—students, lovers, colleagues—whose admiration substitutes for genuine self-worth. Abigail’s admiration briefly revives Ethan’s sense of importance, while Robbie’s devotion flatters Simone’s belief in her own moral and creative superiority.

The novel suggests that identity in adulthood is inherently unstable, particularly when built on external validation. Every act of seduction, whether romantic or intellectual, becomes a performance designed to confirm one’s relevance in a world that constantly threatens obsolescence.

By the end, the characters’ reconciliations—Ethan’s renewed bond with Simone and Robbie’s professional triumph—feel less like resolutions and more like the latest reinventions of self. The search for identity remains perpetual, driven by the same insecurities that fuel desire and betrayal.

Adrian thus portrays human connection as a mirror through which individuals glimpse fleeting reflections of who they want to be, even as those reflections dissolve into disappointment and self-deception.

Morality and Ambiguity

Moral ambiguity saturates Seduction Theory, where no character is entirely innocent or entirely corrupt. The novel dismantles clear distinctions between right and wrong, showing how intellect and self-awareness fail to protect against ethical failure.

Ethan’s affair with Abigail and Simone’s manipulation of Robbie are presented not as moral opposites but as parallel expressions of emotional need and self-delusion. Each justifies transgression through reasoning that collapses under scrutiny: Ethan calls it friendship, Simone calls it research.

The repeated conflation of mentorship and seduction underscores the novel’s central claim—that moral failure often arises not from desire itself but from the refusal to confront it honestly. Adrian refuses to moralize her characters; instead, she invites readers to examine how privilege, gender, and intellect complicate accountability.

Forgiveness becomes another moral grey zone—when Simone chooses to stay with Ethan, it is not an act of absolution but of weary recognition that love and failure can coexist. By the novel’s end, morality has lost its clarity, replaced by a realism that acknowledges how people harm others while still yearning for connection.

The result is a deeply human portrayal of ethical uncertainty, where understanding replaces judgment, and the capacity for empathy coexists uneasily with the capacity for betrayal.