Selected Essays, Poems and Other Writings by George Eliot Summary and Analysis

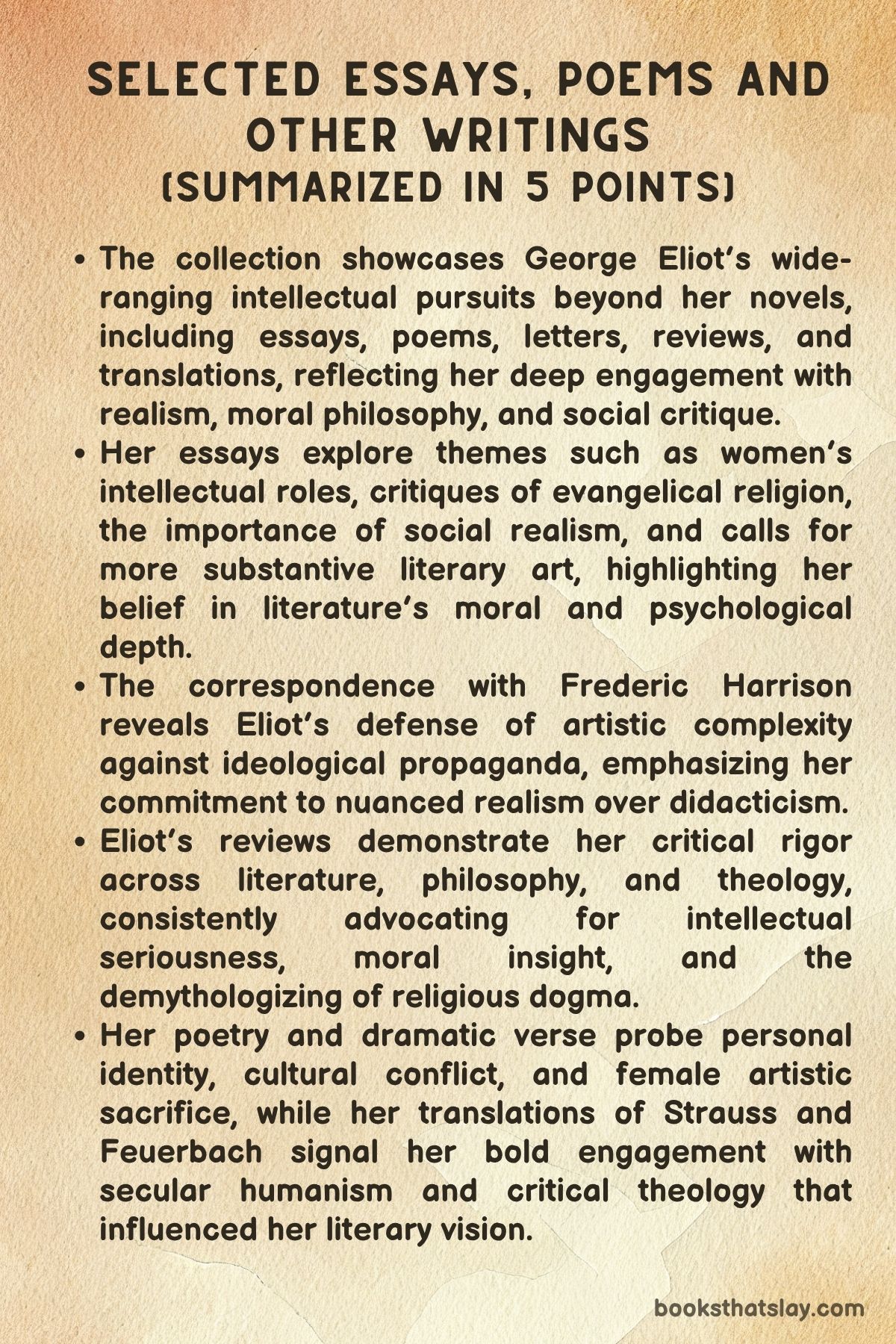

Selected Essays, Poems and Other Writings is a collection of stories that showcases the intellectual breadth and literary genius of George Eliot beyond her famous novels.

This volume gathers her essays, critical reviews, letters, poems, and translations, illuminating the vibrant mind behind works like Middlemarch. Far from mere literary output, these writings offer deep insights into Eliot’s philosophical beliefs, social critiques, and artistic ideals. Through sharp essays and thoughtful correspondence, she wrestles with religion, feminism, realism, and the moral role of literature, blending rigorous intellectual inquiry with vivid literary style.

Summary

In Selected Essays, Poems, and Other Writings, George Eliot presents a rich collection of essays and critiques that explore diverse intellectual domains, from politics and religion to art and literature. This selection not only highlights her literary genius but also showcases her deep engagement with the social and philosophical issues of her time.

One of the key texts in this collection is the Prospectus of the Westminster and Foreign Quarterly Review (1852), a collaborative project between George Eliot and John Chapman. The aim of the prospectus was to relaunch the Westminster Review, a journal that sought to promote progressive intellectual thought.

In the prospectus, Eliot and Chapman outline their commitment to the “Law of Progress,” advocating for reforms in governance, education, suffrage, and religion. Though the initial response to the document was negative, Eliot’s vision for the journal and her meticulous revision of the prospectus ultimately set the tone for the publication’s success.

Under her editorial leadership, the journal became a platform for independent thought and progressive discourse, reflecting the intellectual climate of the time.

One of the collection’s key essays, Evangelical Teaching: Dr. Cumming (1855), critiques the rise of evangelical preachers in England, particularly focusing on Dr.

Cumming, who was known for his rigid, dogmatic interpretations of biblical prophecy. Eliot argues that such preachers cloak mediocrity in the guise of piety and wisdom, using scripture to maintain authority and attract followers.

She criticizes the evangelical movement for prioritizing dogma over compassion, emphasizing that the teachings of preachers like Dr. Cumming promote a worldview where divine glory trumps human empathy.

Eliot’s essay deconstructs the moral implications of such teachings, asserting that they inhibit genuine human connection and undermine natural human sympathy.

In German Wit: Heinrich Heine (1856), Eliot shifts her focus to the German poet and humorist Heinrich Heine. This essay praises Heine for his unique combination of wit, satire, and literary talent, contrasting his humor with that of other European traditions.

While German humor was often seen as lacking refinement compared to French and English wit, Eliot argues that Heine stands as a remarkable exception. His works, such as Buch der Lieder and Reisebilder, blend political insight, poetry, and humor in a way that was unprecedented in German literature.

Eliot also explores Heine’s personal struggles, particularly his complex relationship with politics and his disillusionment with the French Revolution. Heine emerges in Eliot’s essay as a man who, despite his sharp wit, was deeply conflicted about life and his own contradictions, which made him a deeply human figure.

Notes on Form in Art (1868) is another significant essay in the collection, where Eliot explores the concept of “form” in artistic expression. Drawing from her philosophical perspective, Eliot defines “form” as the discrimination of wholes and parts, a process that results in increasingly complex structures in art.

She emphasizes that true artistic form is not about imitation but is instead a reflection of the artist’s emotional state and intellectual rigor. Eliot contrasts the spontaneous nature of early art with the deliberate and reflective process that emerges as art evolves.

However, she warns against the risk of intellectualizing art to the point where its emotional resonance is lost. True art, in Eliot’s view, balances emotional expression with intellectual clarity, offering a living reflection of human experience.

Through these essays, Eliot not only addresses specific cultural and intellectual issues but also reflects her broader philosophy of gradual societal progress. In her view, intellectual growth and reform are essential for the advancement of society, and this is a central theme that runs through much of her work.

Whether discussing the evolution of artistic form or critiquing the religious and political figures of her time, Eliot consistently advocates for a more progressive, compassionate, and intellectually rigorous approach to societal problems.

The essays also reveal Eliot’s nuanced understanding of gender and the social constraints imposed on women. Her own personal experiences as a woman writer and intellectual shaped her critiques of the societal expectations placed on women, particularly in the realms of marriage, motherhood, and professional ambition.

In her fictional works, as well as in her essays, Eliot champions the idea of personal autonomy and the right of individuals, especially women, to pursue their intellectual and artistic callings without being bound by traditional gender roles. This belief in the importance of self-actualization, regardless of societal expectations, is one of the recurring themes in Eliot’s work, and it resonates deeply in her critical essays.

Overall, Selected Essays, Poems, and Other Writings offers readers an insight into Eliot’s intellectual and philosophical world. Her essays engage with the pressing issues of her time—religious dogma, political reform, artistic expression, and gender equality—and offer a sophisticated analysis of these topics.

Eliot’s deep commitment to the idea of progress, both intellectual and social, shines through in her writings, making this collection an essential part of her legacy as a thinker, critic, and writer. Her ability to bridge the gap between intellectual critique and literary artistry ensures that her essays continue to be relevant and thought-provoking today.

Through these essays, Eliot challenges her readers to think critically about the world around them and to consider how progress in both thought and action can lead to a more just and compassionate society.

Analysis of Themes

Gender and Societal Expectations

The narrative explores the tension between individual ambition and societal constraints, particularly with respect to gender roles. Armgart’s struggle illustrates the internal conflict faced by women artists in a world that relegates them to traditional domestic duties.

As a woman of artistic ambition, Armgart is confronted by societal norms that prioritize the roles of wife and mother over the pursuit of public recognition and personal fulfillment. The dialogue between Armgart and Graf reflects the differing worldviews: Armgart’s belief in the primacy of her artistic vocation, and Graf’s belief in the fulfillment of women within the confines of traditional gender roles.

Armgart’s rejection of these constraints is an assertion of her right to self-actualization, showing that the expectations imposed on women can stifle their personal growth and creative potential. She refuses to accept that her gender should limit her professional achievements or the recognition of her artistic contributions. In doing so, she challenges the very notion that women should only find fulfillment in supporting others, particularly in domestic spheres.

Armgart’s choice to remain unmarried and continue her career highlights her rejection of society’s attempt to define her worth based on traditional feminine roles. It is a declaration of independence that signifies the importance of claiming space in the world as a woman, not just as a wife or mother, but as a creator in her own right.

The Conflict Between Artistic Ambition and Personal Sacrifice

Armgart’s relationship with Graf highlights the philosophical tension between personal ambition and the sacrifices that often accompany it.

As an artist, Armgart’s ambition is not driven by vanity but by a deep-seated need to fulfill her creative calling. Her music represents her soul, and to relinquish it for the sake of domesticity would be to betray her very essence.

This theme resonates with the notion that artistic ambition, while deeply fulfilling, often comes at the cost of personal relationships and societal acceptance. Graf, on the other hand, represents the conventional view that a woman’s fulfillment lies in domestic roles, arguing that the pain Armgart will face in her career is inevitable and perhaps not worth the price.

He believes that her artistic dreams will lead to disappointment and that she would find true happiness only in supporting him and raising a family. However, Armgart’s decision to remain unmarried and continue pursuing her art reflects her belief that personal sacrifice is a necessary aspect of artistic growth.

The pain and challenges of pursuing one’s artistic journey are not deterrents to Armgart but are integral to her understanding of fulfillment and purpose. The conflict illustrates how women, in particular, are expected to choose between personal ambition and familial duty, with society often placing the latter in higher regard.

The Nature of Love and Sacrifice

The theme of love, particularly as it relates to sacrifice, is deeply explored through the contrast between Armgart’s ambitions and Graf’s desires.

Graf’s love for Armgart is expressed through his proposal for a life of domesticity, suggesting that she forgo her career and pursue a quieter, more traditional existence as his wife. He views this as an act of love, one where both their lives would be enriched by her embrace of domesticity. However, for Armgart, true love cannot exist in a relationship where she must surrender her identity as an artist.

The tension between them underscores the complexities of love in a world where gender roles dictate what one should love and how one should express that love. Armgart’s love for her art is so profound that she cannot fathom choosing a life without it. The pain and alienation she may experience by remaining unmarried and pursuing her career are consequences she is willing to endure.

Her love for her art is a form of self-love that supersedes conventional expressions of affection or companionship. The narrative thus explores the painful truth that love, especially love between partners, can demand sacrifices, and in some cases, the sacrifices are so profound that they lead to the separation of individuals who may otherwise deeply care for each other.

Individual Identity vs. Societal Conformity

Armgart’s rejection of the traditional roles imposed on her highlights the broader theme of individual identity versus societal conformity. The pressure to conform to societal norms, especially for women, is a central conflict in her struggle.

Armgart’s decision to prioritize her artistic identity over the social expectation of marriage and motherhood emphasizes the need for individuals to assert their personal identity in the face of societal pressure.

Her story serves as a critique of a society that often demands conformity at the expense of individual freedom and fulfillment. Armgart is not simply rebelling against Graf or against the concept of marriage but is also rejecting a world that seeks to confine her to a narrowly defined role. The narrative emphasizes the importance of self-determination and the pursuit of one’s passions, even when these choices lead to isolation or conflict.

It suggests that true fulfillment comes from embracing one’s identity and purpose, regardless of external pressures to conform. In this way, Armgart’s journey becomes a symbol of the struggle for autonomy in a world that insists on limiting personal expression to predefined roles.