Shōgun Summary, Characters and Themes | James Clavellis

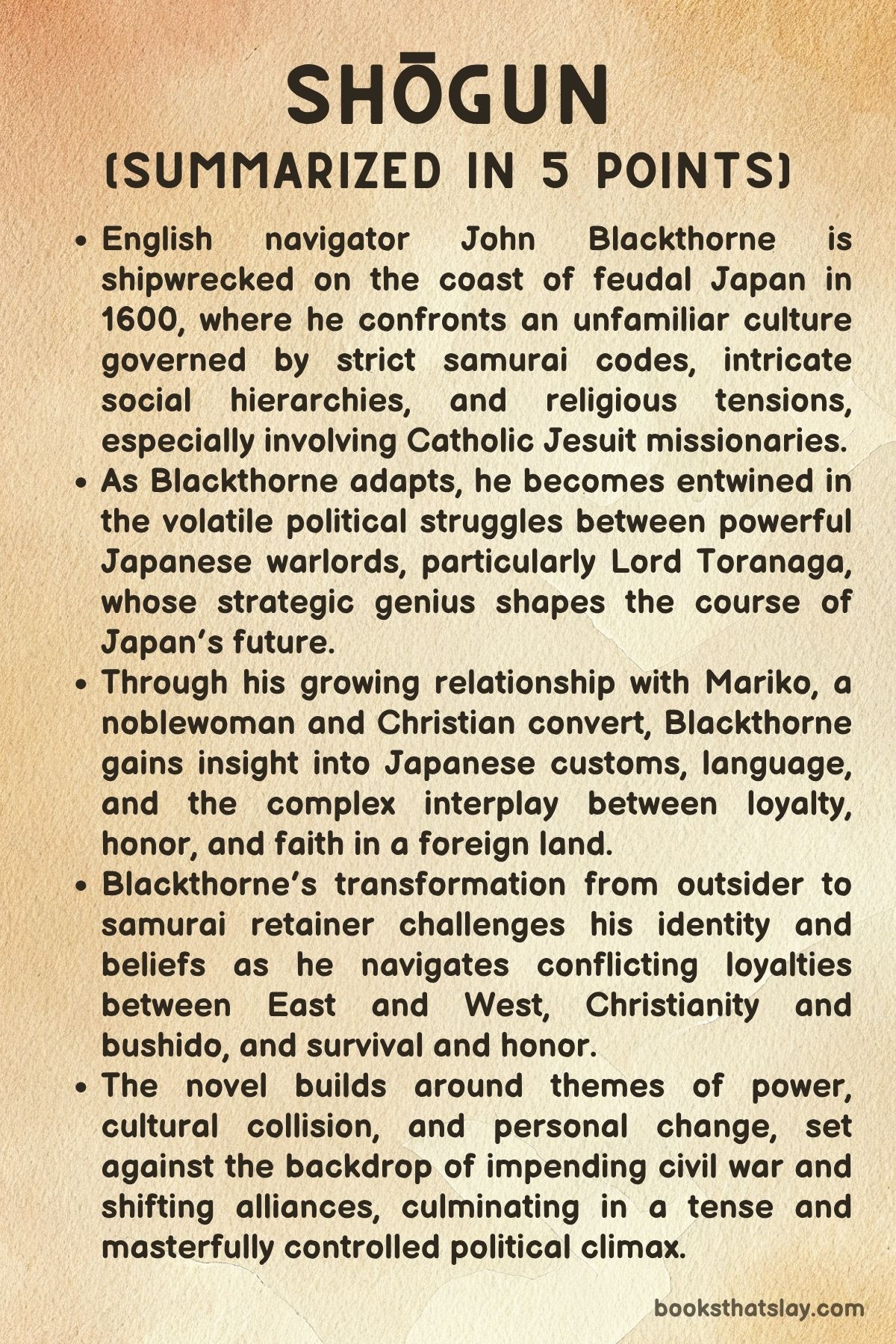

Shōgun by James Clavellis a historical novel set in early 17th-century Japan, during a time of intense political upheaval and cultural collision. The story follows John Blackthorne, an English navigator who becomes shipwrecked on the shores of a foreign land governed by samurai honor, strict social hierarchies, and complex feudal politics.

As Blackthorne struggles to survive and understand this alien world, he becomes entangled in the power struggles of Japanese warlords, the clash between European religious factions, and a profound personal transformation. Clavell’s novel offers a vivid portrayal of a pivotal moment in Japanese history through the eyes of an outsider who is drawn deep into its mysteries and challenges.

Summary

The novel opens with the English ship Erasmus wrecked on the coast of Japan in the year 1600. John Blackthorne, the ship’s pilot, awakens in a strange village where the customs, language, and social rules are utterly unfamiliar to him.

From the outset, Blackthorne faces the harsh realities of feudal Japan, where a strict code of honor governs all actions, and even small missteps can have deadly consequences. He soon learns that the local samurai hold immense power, enforcing justice with swift and often brutal measures. A public execution shocks Blackthorne and reveals the severity of the Japanese legal system.

Tensions rise as Blackthorne encounters Father Sebastio, a Portuguese Jesuit priest who views him with hostility due to their conflicting religious beliefs and European rivalries. The Jesuits, with their deep influence in Japan, see Blackthorne as a dangerous heretic and enemy. Meanwhile, the samurai treat Blackthorne with a cautious respect born from his courage and knowledge, particularly Omi, the local samurai leader who watches him closely.

Blackthorne’s survival depends on learning the language and customs, and with the help of a noblewoman named Mariko, a Christian convert and skilled translator, he begins to navigate the complexities of this foreign land.

Blackthorne is brought inland to the domain of Lord Toranaga, a powerful daimyo engaged in a fierce contest for control of Japan. Toranaga is a shrewd and patient strategist, carefully balancing alliances and rivalries among other warlords, especially his main adversary, Ishido.

As Blackthorne gains Toranaga’s trust, he is elevated to the rank of Hatamoto—a samurai retainer—marking a significant transformation in his identity and status. Toranaga recognizes the value of Blackthorne’s Western knowledge, including navigation and military technology, and uses these skills to his advantage in the delicate political landscape.

Throughout this time, Blackthorne’s bond with Mariko deepens, evolving from mere reliance to a profound emotional connection. She becomes his cultural guide and moral compass, bridging the gap between his European origins and the Japanese way of life.

Their relationship is complicated by their religious beliefs and societal expectations, as well as the escalating tensions between Christian missionaries and traditional Japanese authorities. Mariko’s faith and loyalty to Toranaga place her in dangerous political situations, including serving as an envoy to hostile factions.

As the story progresses, Toranaga’s strategy to avoid outright war involves relocating his court and carefully manipulating the fractured Council of Regents, a governing body rife with ambition and distrust. Blackthorne witnesses acts of ritual suicide, the intricacies of the samurai code of bushido, and the significance of honor and loyalty.

The influence of the Jesuits, once dominant, begins to wane as Toranaga sidelines them, aware of their political motives. Blackthorne throws himself into building a Western-style ship at Toranaga’s behest—part symbol of progress and part potential escape route.

Yet, despite the ship’s near completion, Blackthorne’s life becomes increasingly tied to Japan. His thoughts and actions gradually align with the samurai way, and he contemplates a future where his home is no longer Europe but this foreign land.

The political tension mounts as Toranaga outmaneuvers his enemies through patience, psychological tactics, and strategic alliances. Ishido, Toranaga’s rival, fails to unite the other warlords, weakening their position. Meanwhile, Blackthorne’s status rises, but so do the stakes.

The death of Mariko—a tragic and heroic act during a hostage crisis—leaves Blackthorne devastated and hardens Toranaga’s resolve. This loss forces Blackthorne to reconcile his conflicting identities and embrace his role in Japan’s unfolding history.

As the narrative approaches its final stages, the landscape is set for a profound shift in power, yet the story refrains from direct battle scenes, focusing instead on the intricate play of influence, loyalty, and strategy.

Blackthorne is no longer an outsider merely surviving but a respected samurai intertwined with the fate of a nation on the brink of transformation. The question remains how far he will be able to hold on to his past and what his future holds in this land that has reshaped him so deeply.

Characters

John Blackthorne

John Blackthorne is the central figure through whose eyes the Western reader experiences Japan. Initially an English navigator and pilot of the ship Erasmus, he arrives as an outsider, unfamiliar with Japanese language, customs, and social structure.

His pragmatic and analytical mind allows him to adapt quickly to his new environment, even as he faces suspicion and hostility, especially from the Jesuit priests. Over the course of the novel, Blackthorne undergoes a profound transformation, both culturally and spiritually.

His initial desire to survive shifts into a deeper assimilation, as he learns Japanese language and etiquette, adopts samurai customs, and ultimately becomes a samurai retainer (Hatamoto). His growing relationship with Mariko humanizes Japan for him and softens his identity from an aggressive European to a man who respects and embraces the honor-bound and ritualistic society.

Despite his transformation, Blackthorne remains caught between two worlds, haunted by his past but increasingly accepting that his future lies in Japan. His journey is one of self-discovery, where loyalty, love, and cultural understanding reshape his worldview, culminating in acceptance of his place as a samurai and landowner.

The destruction of the ship symbolizes the final severance from his Western roots and the full embrace of his new identity.

Lord Toranaga

Lord Toranaga is a masterful daimyo whose intelligence and patience drive the political intrigue throughout the story. He is portrayed as a brilliant strategist who prefers psychological warfare, subtle manipulation, and long-term planning over outright violence.

His ultimate goal is to consolidate power and become Shōgun without plunging Japan into chaotic war. Toranaga’s ability to foresee events and outmaneuver rivals, particularly Ishido, underscores his exceptional leadership and political acumen.

He recognizes Blackthorne’s value as a Western expert and uses him as both a tool and a symbol of modernization. Toranaga’s relationship with Blackthorne is complex—he grants him status and land, binding him to Japan, while offering the hope of freedom that remains tantalizingly out of reach.

Toranaga’s character embodies a calm, calculated mastery of power, blending traditional samurai values with an openness to change, as seen in his encouragement of shipbuilding and technology. His long game eventually brings him to the brink of uncontested control, highlighting his skill in transforming Japan’s fractured political landscape with minimal bloodshed.

Lady Mariko

Lady Mariko stands as a pivotal figure who bridges cultural, religious, and emotional divides. A noblewoman and Christian convert fluent in multiple languages, she acts as Blackthorne’s translator, guide, and moral compass.

Mariko embodies the conflict between the old and new worlds: devoutly Christian yet deeply loyal to her Japanese heritage and lord. Her intelligence and diplomatic skills position her at the heart of the political tensions, as she negotiates delicate alliances and risks her life for her beliefs and loyalties.

Her tragic death during a hostage crisis marks a turning point for Blackthorne and for the narrative’s emotional core. Mariko’s sacrifice symbolizes the complex intersections of faith, honor, and personal duty.

Through her, Blackthorne gains profound insight into the contradictions of Japan and the costs of power struggles. Her memory continues to influence Blackthorne’s evolving philosophy and loyalty, cementing her legacy as both a martyr and a catalyst for change.

Ishido

Ishido is Lord Toranaga’s chief rival and a symbol of the old guard resisting Toranaga’s rise. He represents the faction clinging to the existing power structures and traditional dominance.

Ishido’s character is marked by rigidity, paranoia, and a willingness to resort to intimidation and violence to maintain control. His inability to match Toranaga’s patience and strategic subtlety leads to his political isolation.

Ishido’s role is crucial in framing the high-stakes political environment where alliances shift constantly and survival depends on more than brute strength. He acts as a foil to Toranaga’s composed mastery, emphasizing the tension between impulsive action and deliberate strategy within samurai politics.

The Jesuit Priests (Father Sebastio and others)

The Jesuit priests in Shōgun represent the foreign religious and colonial interests competing for influence in Japan. They view Blackthorne with hostility, branding him a heretic and threat due to his Protestant faith and English background.

Their influence over Japanese leaders is substantial but gradually declines as Toranaga sidelines their power. The priests embody the cultural and religious conflicts between East and West, serving as antagonists who attempt to control Japan through faith and fear.

Their dogmatic approach and political maneuvering put them at odds with Toranaga’s pragmatic vision and Blackthorne’s gradual integration. This highlights the complex interplay between religion, power, and colonial ambitions.

Themes

Strategic Mastery of Political Power as a Reflection of Cultural Values and Psychological Warfare

Throughout Shōgun, the novel meticulously explores how political dominance in feudal Japan is achieved not through brute force but through calculated patience, subtle manipulation, and psychological acumen. Lord Toranaga embodies this theme by employing intricate schemes to outmaneuver his rivals without open warfare.

His approach reflects deeply ingrained Japanese values of restraint, honor, and indirect conflict resolution. This political mastery is a cerebral battle where alliances are tested and loyalty is both currency and weapon.

The interplay of power demonstrates how cultural norms shape leadership styles and how control is exercised through social structures and perceptions rather than outright violence.

The novel posits political success as a complex dance where long-term vision and mental fortitude outweigh immediate physical confrontation, revealing an alternative understanding of strength grounded in strategy and cultural sophistication.

Transformation of Identity Through Immersive Cultural Assimilation and the Negotiation of Belonging Between Worlds

John Blackthorne’s journey is an intricate study of identity as a fluid construct, reshaped through immersion in an alien culture.

Initially an outsider marked by his European Protestant background and naval traditions, Blackthorne’s gradual assimilation into Japanese society highlights the psychological and existential tensions of cultural displacement and adaptation.

His elevation to samurai status symbolizes a profound internal transformation where external acculturation merges with inner change.

This theme examines how belonging is negotiated through language acquisition, ritual participation, and the adoption of new ethical codes, while still wrestling with the remnants of his original self.

Blackthorne’s duality—between his European origins and his Japanese present—raises questions about loyalty, authenticity, and the cost of crossing cultural boundaries.

The narrative challenges rigid notions of identity, suggesting that survival and acceptance in a foreign world require the redefinition of one’s self, often accompanied by loss, compromise, and renewal.

Religious Conflict as a Manifestation of Colonial Rivalry and the Clash of Worldviews in a Politically Fragmented Landscape

The tensions between Protestant Blackthorne and the Catholic Jesuits underscore a deeper theme of competing imperial and religious ambitions within the broader context of Japan’s political fragmentation.

The novel reveals how faith serves not only as spiritual belief but as a political instrument wielded by European powers to secure influence in the East.

The Jesuits’ fear of losing their monopoly and their resistance to Blackthorne’s presence exemplify the intersection of religious dogma and colonial rivalry.

This theme explores the friction between imported Christian ideologies and native Japanese traditions, exposing how religion can both divide and unite.

Moreover, it addresses the complexities of syncretism and rejection, as Japan cautiously negotiates its openness to foreign ideas amid internal power struggles.

The religious dimension is not merely theological but deeply entangled with questions of cultural sovereignty, control, and survival in a world where faith is inseparable from politics.

Ethical and Philosophical Reconciliation of Contrasting Moral Systems Amidst Personal Loss and Cultural Dislocation

Blackthorne’s evolving worldview reflects a profound engagement with contrasting ethical frameworks—Western individualism and Protestantism versus the Japanese bushido code and collective honor. His personal grief over Mariko’s death and his encounters with practices like seppuku confront him with concepts of sacrifice, loyalty, and dignity that challenge his previous beliefs.

The novel probes the tension between these moral systems, revealing moments where Japanese concepts of honor and fate resonate more deeply than Blackthorne’s Western rationalism. This theme grapples with the difficulty of reconciling disparate worldviews while maintaining personal integrity.

It explores how loss and cultural upheaval catalyze philosophical growth, compelling characters to question fate, free will, and the nature of justice. Blackthorne’s journey is thus not only political or cultural but existential, representing the human capacity to find meaning and ethical clarity in the face of alien traditions and personal tragedy.

Technological Innovation and Material Culture as Both Liberation and Imprisonment Within a Shifting Historical Context

The construction of the Western-style ship stands as a powerful symbol in the novel, embodying the tension between potential freedom and the inescapability of cultural entanglement. For Blackthorne, the ship represents a tangible connection to his homeland and a possible means of escape.

However, its near destruction and ultimate loss signify the severing of his last link to the West, illustrating how technological progress can simultaneously enable and confine.

This theme reflects broader historical realities where material culture and technological exchange are imbued with political and symbolic significance.

The ship’s fate metaphorically encapsulates the complexities of cross-cultural encounters in an era of emerging global trade and imperial ambitions, suggesting that innovations can carry unintended consequences—freedom intertwined with deeper submission to new social orders.

The motif invites reflection on how technology interacts with identity, sovereignty, and the limits of personal agency amid historical forces.