Shy Creatures Summary, Characters and Themes

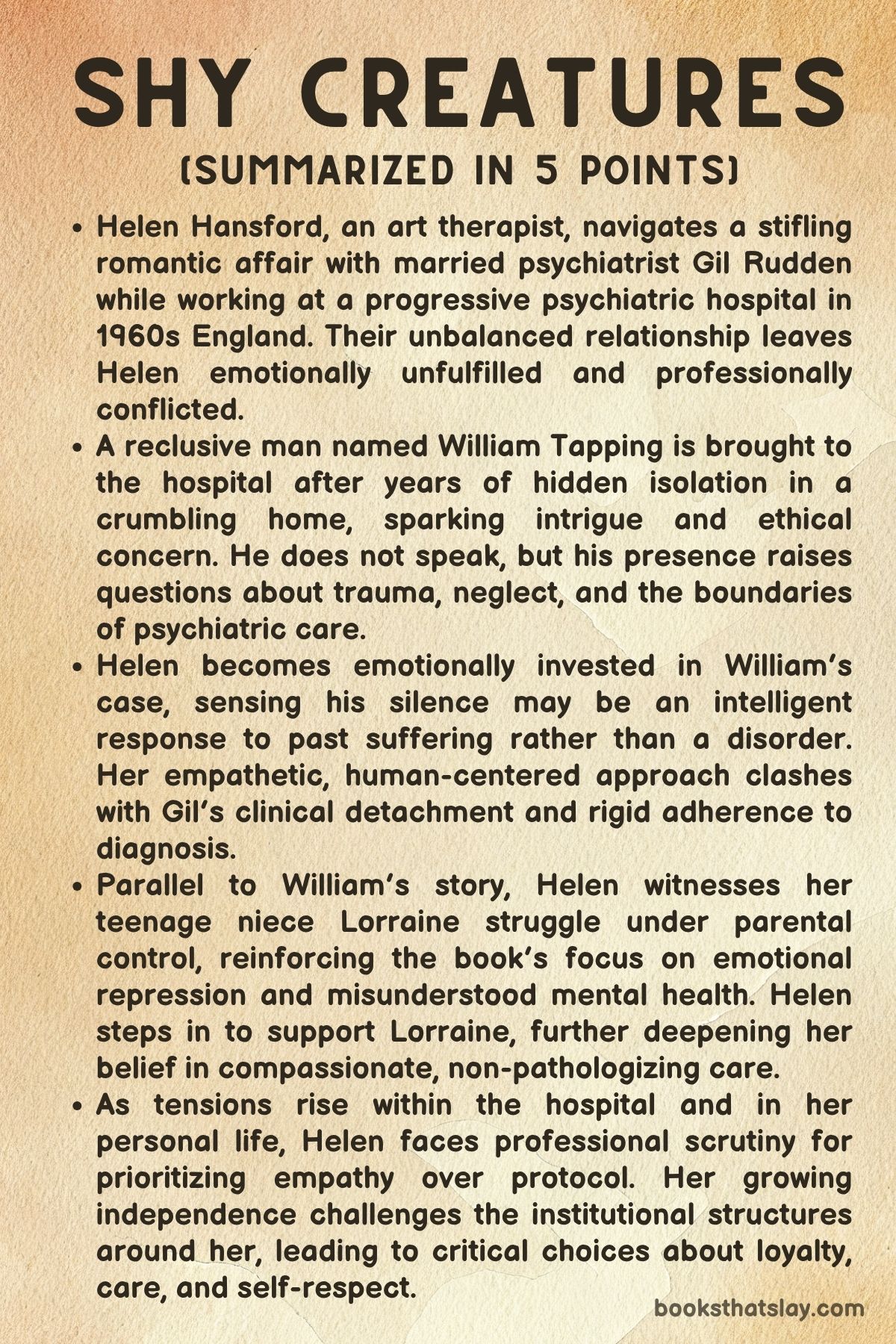

Shy Creatures by Clare Chambers is a psychologically astute and emotionally resonant novel that explores the complex intersections of love, professional ethics, mental illness, and personal growth.

Set against the backdrop of a psychiatric hospital in England, the narrative follows Helen, an art therapist, as she navigates the demands of her work and the turmoil of an affair with a charismatic but morally conflicted psychiatrist named Gil. Through interconnected stories of patients and professionals, Chambers gently but unflinchingly examines human vulnerability, the hunger for connection, and the quiet, incremental path toward healing and self-respect.

Summary

Helen’s story begins with quiet introspection and a deep sense of retrospection. She recalls a specific weekend as the moment her romantic relationship with Gil began to unravel—an affair marked from its inception by secrecy, emotional dependency, and ethical ambiguity.

Helen works as an art therapist at Westbury Park, a psychiatric hospital, and takes pride in the safe, creative space she has cultivated for her patients, particularly for male alcoholics for whom traditional therapy is often too raw. Gil, a married psychiatrist with visionary views on mental healthcare, draws Helen in with his charm and progressive ideals.

However, his personal life fails to live up to the intellectual intimacy he offers professionally.

Their affair intensifies when Gil suddenly becomes available for a weekend retreat. Helen cancels a long-standing family plan to be with him, making excuses that cause her real guilt.

She prepares eagerly for their time together, investing domestic and emotional energy into an illusion of intimacy. But when Gil cancels due to a minor car accident involving his wife, Kathleen, Helen’s entire emotional framework collapses.

The pain of being a secondary priority is acute, and the elaborate preparations she had made feel pointless and humiliating. This turning point exposes the fragility of their relationship.

Running parallel to Helen’s emotional journey is the haunting story of William Tapping and his elderly aunt Louisa. William, mute and emotionally shut down, is discovered barricaded in a decaying Croydon home with Louisa, who is suffering from dementia.

Their shared life had been one of extreme isolation and eccentric routine, which the outside world misinterprets as neglect and pathology. Helen and Gil become deeply involved in William’s case.

Louisa insists on William’s normalcy despite clear signs of trauma and dysfunction. William’s interactions are marked by outbursts and strange rituals—like keeping a magpie in the fridge and engaging in destructive fights with Louisa over seemingly minor issues.

After their admission to Westbury Park, clinical evaluations suggest William may have been voluntarily mute or psychologically damaged by long-term isolation. Yet Helen discovers his hidden suitcase of artwork, filled with astonishingly skillful and emotionally expressive drawings.

This discovery shifts the perception of William from a passive victim to a repressed but richly inner-driven individual. Helen, moved by the intensity of his visual language, offers him his pen and gently invites him into the art studio.

When he eventually whispers a soft “thank you,” it signals a breakthrough and the beginning of a fragile but important transformation.

Gil, meanwhile, advocates for non-traditional treatment approaches. He resists medicating or confining William, believing in patience and dignity.

This philosophy occasionally puts him at odds with hospital protocol but also strengthens Helen’s admiration for him. She sees Gil as an intellectual equal and a compassionate clinician, though his inability to offer the same clarity and commitment in his personal life gradually becomes more glaring.

When Louisa dies, William is left alone for the first time in decades, his grief manifesting quietly. He begins forming a silent bond with the hospital cat, and Helen deepens her investment in his wellbeing.

Helen’s personal and professional worlds collide again when Lorraine, her teenage niece, has a psychological breakdown during an exam and is admitted to the hospital. Helen distrusts Lorraine’s assigned psychiatrist, Dr.

Lionel Frant, and appeals to Gil to take over. When he declines due to hospital policy, Helen appeals to the superintendent, who also refuses.

This rejection underscores the limitations of Helen’s influence and the blurred lines she has crossed by involving herself so deeply in others’ lives. Further strain emerges when Helen and Gil go on a countryside picnic, meant to be a romantic respite.

The outing is derailed by Gil’s confession that Kathleen is pregnant again—a fact he had withheld. The symbolism is unmistakable: wine spills, wasps attack, and their illusion of happiness falls apart.

Helen begins to see Gil more clearly, less as a partner and more as a man unwilling to leave his stable domestic life.

Later, a surprise visit by Francis Kenley and his mother Marion—figures from William’s childhood—brings about an emotional climax. The reunion is raw and deeply emotional.

William, overwhelmed but cooperative, confronts the past he had buried. He returns a napkin ring—a small memento that symbolized their bond—and slowly begins speaking again.

The warmth and acceptance from Marion, along with Francis’s mix of guilt and love, help unearth William’s long-repressed memories. Through this encounter, William’s humanity is recognized not through diagnosis, but through personal history and emotional truth.

Tensions escalate when Gil is attacked at the hospital, and Helen is the only person who stays with him through the night. Still, she recognizes the limits of her role in his life.

She does not accompany him to the hospital, knowing that role belongs to Kathleen. Her subsequent call to Kathleen, tinged with heartbreak and honesty, finalizes the end of their affair.

Around the same time, Lorraine disappears briefly but returns home unharmed. William, too, runs away but is found by Helen in the ruins of the Tapping home, frightened and convinced he has done something wrong.

Their emotional exchange, especially his reading of a letter from his birth mother revealing his hidden parentage and adoption, deepens the story’s exploration of secrecy and emotional suppression.

In a redemptive turn, Helen approaches Lionel Frant to apologize for her earlier actions regarding Lorraine. Their conversation fosters a new level of mutual respect.

Lionel’s calm, principled demeanor contrasts with Gil’s erratic brilliance, and Helen begins to value the steady and honest over the idealized and impulsive. William finds a new home with Marion at Brock Cottage, where he thrives, helping with gardening and dog training.

Helen’s final visit reveals a William at peace, living a life of dignity and connection.

Helen also finds resolution with Lorraine, who is slowly recovering and beginning to consider returning to school. Their shared moment of intimacy and forgiveness marks a renewal of trust and hope.

Gil, having lost his chance at promotion, plans to leave for an experimental therapeutic commune. Their final conversation is subdued and resolute—Helen refuses to romanticize the past, declaring that she wishes they had never become lovers.

She moves out of the flat he once paid for, symbolizing a reclaiming of her autonomy.

The novel closes with grace and emotional authenticity. William, having reconnected with parts of his identity and family, lives peacefully at Brock Cottage.

Helen, now free from the emotional entanglements that once defined her, is open to new possibilities. A visit from Francis hints at the potential for a new chapter in her life, one grounded not in secrecy or longing but in mutual respect and emotional clarity.

In the end, Shy Creatures offers a moving meditation on healing, autonomy, and the quiet power of human connection.

Characters

Helen

Helen stands at the emotional core of Shy Creatures, a deeply introspective and morally conflicted character whose evolution defines much of the novel’s narrative power. As an art therapist, Helen is initially presented as competent and passionate about her work, creating a nurturing, nonjudgmental space for patients through artistic engagement.

Yet beneath her professional calm lies a woman yearning for intimacy and understanding, which leads her into a secretive and ultimately destructive relationship with Gil. Her affair is laced with guilt, longing, and a desperate need for emotional reciprocity.

Over time, Helen’s self-perception becomes increasingly tied to Gil’s affection, resulting in emotional isolation and compromised ethics. However, her character undergoes a significant transformation.

Through her interactions with patients like William, and her deepening moral awareness, Helen begins to reclaim her autonomy. She confronts the uncomfortable truth of being the “other woman,” distances herself from the romantic illusions she once clung to, and takes painful but empowering steps—ending her relationship with Gil, advocating for her niece Lorraine, and finding common ground with Lionel Frant.

Helen’s journey is one of reclaiming integrity and rediscovering meaningful connection, offering a poignant portrayal of a woman extricating herself from emotional entrapment toward clarity and strength.

Gil

Gil, the married psychiatrist, is a study in contradictions—a man of philosophical brilliance and charismatic leadership who fails catastrophically in personal accountability and emotional transparency. He begins the narrative as an alluring figure to Helen, intellectually captivating with his progressive views on psychiatric care and his disdain for institutional rigidity.

His idealism in the clinical setting, especially his defense of patient dignity in cases like William’s, reveals a humane streak that distinguishes him from his more bureaucratic peers. However, Gil’s personal life tells a different story.

His charm masks a profound evasiveness and selfishness. He compartmentalizes his emotions, deflects accountability, and manipulates the affections of others without full commitment.

His failure to tell Helen about his wife’s pregnancy, his indifference to the power imbalance in their affair, and his eventual retreat into a therapeutic commune underscore his inability to face emotional complexity honestly. Gil functions as both a catalyst and a cautionary figure in the novel—someone who ignites change in others but cannot evolve himself.

His departure from Helen’s life feels less like loss and more like liberation, marking the end of delusion and the beginning of reality for those he leaves behind.

William Tapping

William Tapping is perhaps the most enigmatic and quietly compelling character in Shy Creatures, representing the novel’s central exploration of repression, trauma, and the redemptive power of recognition. Introduced as a mute and severely neglected man living in reclusive squalor with his aunt Louisa, William initially appears to be an emblem of institutional failure.

However, as the narrative delves deeper into his world, a rich inner life emerges. His silence is not void but resistance—his drawings reveal extraordinary artistic ability, emotional nuance, and a longing for connection.

William’s trajectory from neglected patient to expressive individual is handled with subtlety and grace. His few spoken words—especially the faint “thank you” to Helen—carry immense weight, suggesting deep appreciation and tentative trust.

His reunion with Francis and Marion reignites buried memories and highlights his capacity for emotional engagement. Even in his disappearance, William does not regress but seeks solace in the symbolic and literal ruins of his past.

The revelation of his maternal history and his peaceful new life at Brock Cottage with Marion bring a gentle resolution to his story. William, once overlooked, becomes a quiet testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the enduring need for dignity and love.

Louisa Tapping

Louisa is a tragic and haunting figure whose decline mirrors the decay of the home she shares with William. Exhibiting signs of dementia, Louisa clings to an outdated and distorted view of their life, denying William’s suffering and her role in his prolonged isolation.

Her interactions are marked by delusion, denial, and flashes of desperate affection, painting a portrait of someone overwhelmed by the enormity of caregiving and the burden of secrecy. Louisa’s world is governed by eccentric routines and symbolic objects—like the magpie in the fridge—which underscore her disconnection from reality.

While her actions may seem neglectful, they also suggest a confused, perhaps misguided attempt at protection. Her sudden death serves as both a narrative turning point and a release—for William, who had been emotionally and physically trapped by their insular bond.

Despite her failings, Louisa is not portrayed as a villain but as a deeply flawed woman shaped by isolation, familial obligation, and mental deterioration.

Lorraine

Lorraine, Helen’s niece, adds a generational echo to the novel’s central themes of vulnerability, identity, and emotional suppression. Her sudden breakdown during an exam and subsequent admission to Westbury Park spark both a familial and professional crisis for Helen.

Lorraine’s struggle with mental health is portrayed with sensitivity, emphasizing not only her fragility but also the strength of her will—evidenced by her voluntary return home and her willingness to confront difficult truths. Her relationship with Helen is strained yet filled with potential for healing.

The reconciliation between them, built over shared vulnerability and mutual apologies, becomes one of the most emotionally satisfying arcs in the novel. Lorraine represents both a mirror and a future for Helen: a reminder of past mistakes and a chance for renewal through honesty and trust.

Lionel Frant

Lionel Frant, though initially viewed with suspicion by Helen, emerges as a quiet stabilizing force within the hospital. He represents a more measured, emotionally neutral form of psychiatry, contrasting with Gil’s intense, ideologically driven approach.

Lionel is pragmatic, respectful of boundaries, and—importantly—open to being proven wrong. Helen’s initial dismissal of him, based on loyalty to Gil and maternal instinct toward Lorraine, gives way to a more balanced view after their candid conversation.

In this, Lionel becomes a surprising ally. His integrity and quiet authority offer a grounded alternative to Gil’s chaos, and by the end of the novel, he commands Helen’s respect and trust.

Lionel’s character arc reinforces the idea that competence and compassion often lie beneath modest exteriors.

Marion

Marion, Francis’s mother and a peripheral figure at first glance, becomes a crucial emotional anchor for William and a symbol of enduring compassion. Her presence during the reunion with William is maternal, calm, and deeply empathetic.

She accepts him without judgment or fear, offering him the kind of home and human warmth he had long been denied. Her invitation to William to stay at Brock Cottage transforms her from a secondary character to a pivotal figure in his healing journey.

Marion’s steadiness and quiet generosity contrast with the institutional coldness William had previously known. She serves as a surrogate mother, embodying the unconditional acceptance that allows William to finally thrive.

Francis Kenley

Francis Kenley’s reentry into William’s life is laced with personal grief, discomfort, and unresolved childhood memories. Though he initially struggles with the emotional weight of reconnecting with someone he knew decades ago, Francis ultimately plays a critical role in affirming William’s sense of worth and shared history.

His discomfort at the hospital meeting contrasts with Marion’s ease, highlighting his own emotional repression and loss. Yet his presence alone is a gift to William—a bridge to the past and a testament to the significance of seemingly forgotten bonds.

Francis’s visit to Brock Cottage in the closing scenes of the novel suggests the possibility of a future relationship with Helen, subtly linking the themes of healing and new beginnings across all the central characters.

Themes

Emotional Dependency and the Cost of Secrecy

Helen’s relationship with Gil is marked by a deep emotional dependency that she struggles to justify, even as it chips away at her self-worth. Her clandestine position as the “other woman” forces her to compartmentalize her feelings, lying to her family and isolating herself from friendships and professional confidants.

This secrecy becomes corrosive, building an internal tension that manifests as physical discomfort and psychological distress. The excitement of their affair initially gives her a sense of meaning and validation, especially in the emotionally demanding world of psychiatric care where she often feels unseen.

However, as Gil continually prioritizes his family and professional obligations, Helen’s marginal position grows intolerable. The canceled weekend—which she had so carefully prepared for—is a subtle but devastating blow, revealing just how little power she holds in the relationship.

Her realization that she has no one to confide in underscores the emotional solitude of being tethered to someone unavailable. The gradual disintegration of their bond, punctuated by Helen’s inability to fully confront Gil’s betrayals until it is too late, exposes the high emotional cost of loving in secrecy.

The relationship’s secrecy doesn’t protect their intimacy; it suffocates it, and in the end, it denies Helen not only love but also dignity. This theme is intricately explored through everyday moments—missed calls, guilt-laden lies, and unacknowledged sacrifices—culminating in the quiet yet irreversible realization that what she mistook for love was sustained only by her silence and self-erasure.

The Ethics of Care in Psychiatric Institutions

The novel provides a nuanced exploration of psychiatric care, contrasting institutional protocol with humane engagement. Through characters like Helen and Gil, readers see the ethical dilemmas faced by mental health professionals who must navigate between regulatory constraints and emotional intuition.

Gil’s approach, favoring dignity and observation over sedation and confinement, is at once inspiring and troubling. His choices—like giving William garden privileges or resisting the urge to medicate—challenge the hospital’s standard operating procedures and provoke suspicion among his colleagues.

These moments provoke questions about the thin line between innovation and recklessness. Helen’s refusal to read William’s private letters similarly points to an ethic of respect, valuing the inner world of the patient over voyeuristic or professional curiosity.

However, ethical complexities emerge when personal relationships entangle with professional responsibilities, as seen when Helen tries to manipulate the hospital hierarchy to reassign her niece’s care. The refusal she receives reflects institutional boundaries meant to protect objectivity, yet also hints at a system that sometimes prioritizes order over individual well-being.

William’s case becomes emblematic of these tensions: his recovery is catalyzed not by formal treatments but by human connection, patience, and an environment that allows for expression. Yet such an approach is fragile, dependent on individual advocates rather than institutional systems.

The story critiques the shortcomings of psychiatric institutions without vilifying them, suggesting that ethical care is not only a matter of policy but of presence, respect, and the recognition of patients’ full humanity.

Isolation, Memory, and Repressed Trauma

William’s and Louisa’s reclusive life forms a haunting meditation on the enduring effects of trauma and the loneliness it engenders. Their decaying Croydon home, barricaded from the outside world, serves as both literal and symbolic refuge—a fortress against scrutiny and a mausoleum of memory.

William’s muteness, far from being a symptom of madness, emerges as a response to years of suppression and emotional abandonment. His silence becomes a form of resistance, a refusal to participate in a world that long ago dismissed his worth.

Yet his meticulously rendered artwork tells another story, one of sensitivity, intelligence, and unexpressed pain. Helen’s discovery of his drawings marks a turning point, revealing that beneath his apparent dysfunction lies a coherent and emotionally rich inner life.

Louisa’s dementia and denial similarly reflect a life warped by isolation, clinging to distorted narratives to make sense of a tragic past. Their shared rituals—grotesque yet strangely tender—are attempts to preserve a sense of connection and control.

The return of figures from William’s past, particularly Francis and Marion, reactivates buried memories and unresolved grief. The emotional reunion does not produce catharsis, but it opens a crack in William’s silence, allowing him to speak, however falteringly.

The novel’s sensitivity in portraying trauma as something lived in the body, not always articulated in words, positions memory not just as recollection but as a living burden. William’s story insists on the need for patient recognition, where healing begins not with diagnosis but with being seen.

The Illusion of Control and the Need for Surrender

Throughout the novel, characters grapple with their need to exert control—over relationships, professional outcomes, and personal narratives. Helen’s fastidious preparation for her weekend with Gil, her attempts to engineer her niece’s treatment plan, and her resistance to Lionel’s involvement are all efforts to protect her version of events.

These actions stem from a fear of vulnerability, of being rendered powerless in a world that often feels indifferent. Yet control proves illusory.

Gil’s unavailability, Lorraine’s breakdown, and William’s disappearance all force Helen to confront her limits. Even her role as a therapist—rooted in the idea of guiding others toward insight—is called into question when she must accept that healing often defies linearity or logic.

Her eventual recognition of Lionel’s value, and her apology for bypassing him, mark a significant turning point. In these moments, Helen stops trying to fix or direct and begins to accept, bearing witness instead of intervening.

This surrender is not defeat but growth. Similarly, Gil’s fall from grace at the hospital reveals the consequences of his own unchecked autonomy, as he is forced to leave the institution he once helped shape.

William’s journey also mirrors this theme: his ability to speak and engage returns not through force or therapy but through safety and genuine connection. In surrendering to uncertainty—whether through silence, grief, or confession—characters find a form of liberation that control could never offer.

The narrative suggests that the truest strength lies not in mastery, but in the courage to let go.

Reconnection, Redemption, and the Fragile Nature of Hope

As the narrative nears its conclusion, redemption takes center stage, not as a dramatic reversal but as a series of quiet, restorative gestures. Helen’s journey toward moral clarity is shaped by her willingness to acknowledge past mistakes—not only with Gil but with her family and colleagues.

Her reconciliation with Lorraine is especially moving: an apology offered over hair curlers and cake becomes a moment of deep emotional repair. Helen’s departure from the apartment Gil paid for, and her rejection of a romanticized past, mark her return to herself.

Redemption in the novel is not about heroism but about choosing presence over escape, humility over certainty. William’s placement at Brock Cottage, with Marion’s unconditional acceptance, provides him a second chance at life.

The peace he finds is hard-won and deeply meaningful—a home, a garden, and a sense of purpose previously denied to him. Gil’s exit from Westbury Park is tinged with melancholy, but even this loss carries a sliver of potential: he finally confronts his failures and seeks a new path, albeit outside the structures he once defied.

The novel closes with a sense of cautious optimism. Francis’s return, William’s gentle flourishing, and Helen’s restored relationship with Lorraine all hint at the possibility of happiness, though tempered by the awareness of how fragile it is.

Redemption here is quiet, earned not through dramatic transformation but through persistence, vulnerability, and the enduring human need to be loved and understood. In this way, Shy Creatures honors the resilience of its characters and the power of connection to restore what once seemed broken.