Silent Night Summary, Characters and Themes | ML Philpitt

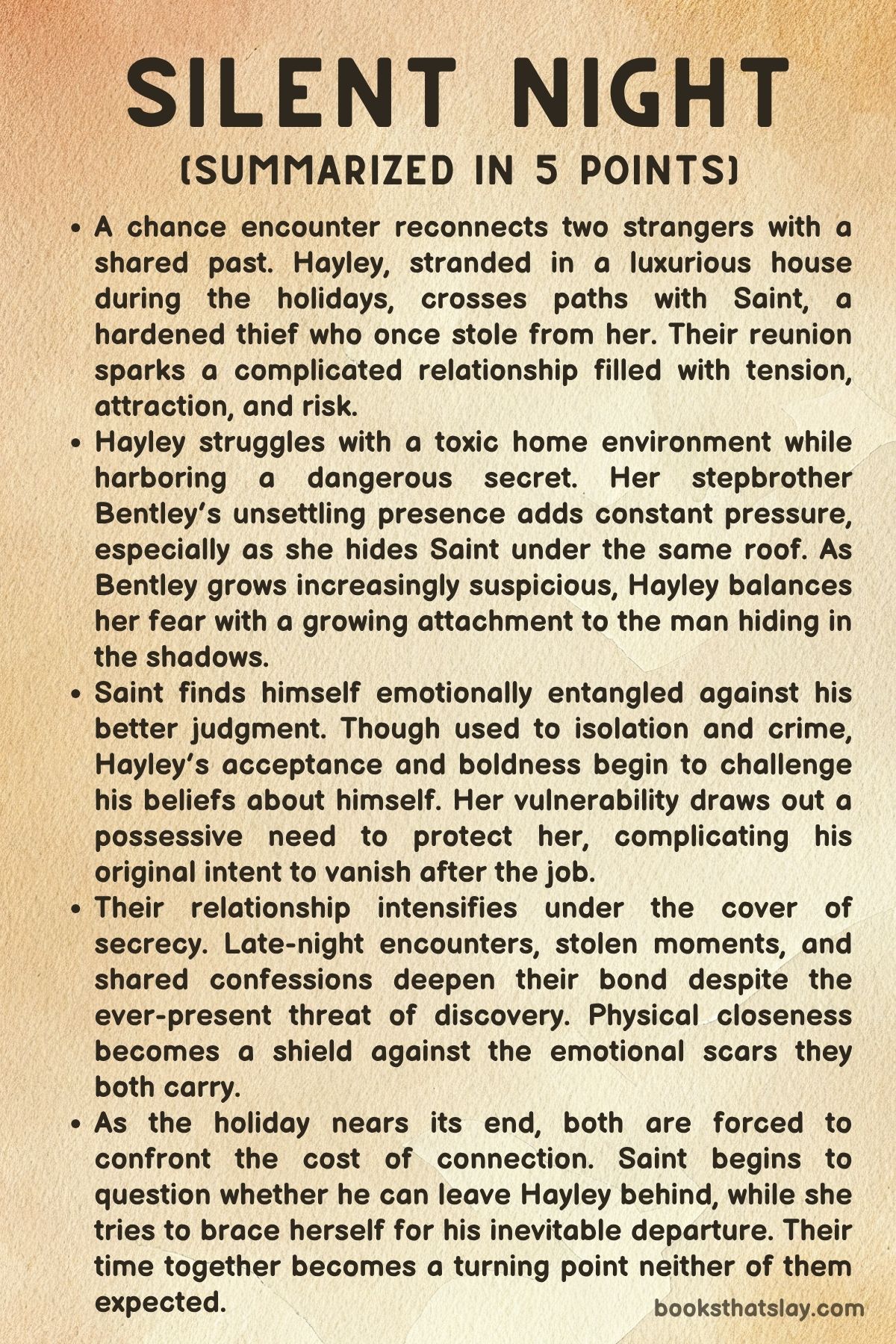

Silent Night by ML Philpitt is a gritty, emotionally charged romance that dives into the lives of two damaged souls navigating love, loss, and survival. Set during the emotionally heightened holiday season, the novel follows Saint, a man hardened by a life of abandonment and crime, and Hayley, a young woman suffocating under the weight of a toxic home life.

Their story is not a conventional romance; it’s a collision of trauma, desire, and the fragile hope of redemption. With dark emotional undercurrents and provocative themes, the book explores how connection can form in the most unlikely of places and how love can emerge even in the shadows of pain.

Summary

Silent Night opens with Saint, a homeless thief shaped by years of neglect and systemic failure, expressing disdain for Christmas and the materialism it represents. To him, the holiday is not only a reminder of society’s greed but also a painful symbol of his own abandonment—he was thrown out of foster care on his birthday, which happens to be Christmas Day.

His survival now depends on robbing the wealthy, a lifestyle he rationalizes by believing the privileged won’t miss what he takes. However, his cynical outlook begins to unravel when he breaks into a house and unexpectedly encounters someone from his past.

Four years earlier, a teenage Hayley had caught Saint during a burglary on Christmas Eve. Instead of reporting him, she let him go and even allowed him to take a valuable dagger with him.

That moment changed Saint’s life—it gave him both his first real heist and a memory of someone who didn’t treat him like a criminal. Now, years later, Saint breaks into another upscale home only to discover it belongs to Hayley again.

She is no longer a naive teen but a disillusioned college student, abandoned by her vacationing parents and left alone with her predatory stepbrother, Bentley.

Recognizing Saint, Hayley chooses once again to protect him. She hides him from Bentley, gives him expensive gifts, and even invites him into her room.

Their connection reignites, burning with both longing and danger. For Saint, Hayley’s continued kindness and vulnerability trigger an obsession—she is unlike anyone he’s ever met.

For Hayley, Saint’s unpredictable, dangerous presence offers a strange kind of safety and escape from her emotionally barren life. Despite the power imbalance and ethical ambiguity, their bond deepens rapidly, transforming into a physical relationship charged with emotional intensity.

As their relationship grows more intimate, Saint begins to see Hayley not just as a refuge but as someone worth staying for. Meanwhile, Hayley finds herself increasingly complicit in Saint’s thefts—not out of fear, but because she sees them as an act of agency.

She is tired of being invisible in her own home and seeks something that makes her feel alive. Their relationship becomes a way to rewrite their stories—Saint from victim of abandonment to protector, and Hayley from passive bystander to someone who makes her own choices.

However, the simmering tension with Bentley escalates dramatically. One night, Bentley becomes violent, attempting to assault Hayley.

Saint, who had been watching from outside, storms in and kills Bentley in a moment of protective rage. The aftermath is bloody and chaotic, but it also solidifies their bond.

Hayley claims self-defense to the police, covering up Saint’s involvement entirely. In this shared act of secrecy, their relationship transforms from something illicit to something irrevocably binding.

When Hayley’s mother and stepfather return, the fallout is complex. Her mother remains emotionally distant and dismissive, while Dean—Bentley’s father—surprisingly shows Hayley compassion rather than blame.

Though the legal case against her is dismissed, Hayley is left emotionally raw. She returns to college, believing Saint is gone from her life for good.

Her sense of loss is profound, but a clue he leaves behind—a pink leather journal—suggests otherwise. The journal, filled with affirmations and messages, becomes a symbol of Saint’s belief in her, pushing her to discover what she truly wants beyond the limits imposed by her past.

Saint, on the other hand, cannot stay away. After using Hayley’s social media to find her, he gets a job and an apartment near her university.

On Valentine’s Day, he breaks into her apartment—not as a thief, but as someone desperate to be with the only person who made him feel human. Their reunion is raw and full of emotional honesty.

Saint lays bare his fears, his need for her, and his commitment to stay and build something real. Hayley, still reeling from everything they’ve been through, welcomes him back with a vulnerability that signifies her own desire for permanence and healing.

In the final chapters, the focus shifts to a sense of tentative hope. Saint and Hayley begin to imagine a future not shaped by trauma and fear but by trust and mutual devotion.

Their love remains morally complicated, shadowed by violence and secrecy, but it is also the most genuine thing either of them has known. Saint chooses to stop running, symbolically and literally, and commits to staying with Hayley—not just for her, but for the version of himself that only she could help him see.

Their bond, forged in a crucible of pain and need, becomes their salvation.

Silent Night ends not with a perfect resolution but with the promise of something real. The world may never understand or accept the foundation of their love, but within it lies a rare kind of truth—two broken people finding in each other the strength to begin again.

The story is unapologetically raw, sensual, and challenging, yet at its heart lies a tender plea for recognition, redemption, and the fierce hope that even the most scarred souls can be worthy of love.

Characters

Saint

Saint is a character molded by the brutal edges of neglect, abandonment, and marginalization. Born on Christmas and expelled from the foster system on that very day, his life has been a cyclical confrontation with rejection and institutional failure.

Saint is homeless, a drifter, and a thief who rationalizes his crimes with sharp clarity, targeting the wealthy under the belief that they won’t notice what they lose. His world is governed by a sense of justice warped by survival, and this ideological cynicism manifests in his scathing monologue on greed and Christmas—a season he equates with both societal hypocrisy and personal pain.

Despite this hardened exterior, Saint is emotionally raw and deeply vulnerable. His memory of a brief encounter with Hayley years ago has imprinted itself so thoroughly in his psyche that it fuels his need to see her again.

That moment of unexpected kindness—her letting him go and giving him the dagger—becomes his emotional anchor in an otherwise bleak existence.

In his interactions with Hayley, Saint’s complexity deepens. He is drawn to her not just as a romantic or sexual partner, but as a representation of something pure and redemptive in a world that has offered him nothing but cruelty.

The more Hayley offers trust, the more Saint’s defenses crack, revealing a man who yearns to be known and accepted but doesn’t believe he deserves it. His obsession with her becomes both a protective instinct and a dangerous fixation, culminating in his inability to leave her behind despite believing that he should.

Even after committing murder to protect her, his first instinct is to disappear for her safety, but his emotional tether compels him to return, attempting to forge a new life. Saint’s arc is one of hesitant transformation—from thief and loner to a man who dares to want a future, not just survival.

Hayley

Hayley is introduced as a young woman navigating the emotional wreckage of a profoundly dysfunctional family. Her mother is self-absorbed and largely absent, while her stepbrother Bentley poses a constant, leering threat.

This toxic domestic environment has left her starved for affection, validation, and autonomy. It’s in this vacuum that Saint returns to her life, and rather than reacting with fear or moral panic, she embraces the danger he represents.

Her attraction to Saint is rooted in his authenticity and in the escape he offers from her suffocating reality. Hayley is not merely a passive character swept along by events; she is complicit and intentional in her choices, including hiding Saint, giving him gifts, and initiating their physical intimacy.

Her willingness to defy social norms and laws isn’t driven by naivety but by a conscious decision to assert control in a life where she’s otherwise silenced and dismissed.

Her evolution is marked by increasing emotional boldness and a hunger for something real. When Bentley assaults her, Hayley’s earlier instincts—to shield Saint—are reversed, and it is he who becomes her protector.

After Bentley’s death, she makes the calculated and courageous decision to cover for Saint, exposing her willingness to bear the consequences of her choices. Even when she believes Saint has left for good, she doesn’t retreat into victimhood but moves forward, continuing her education and maintaining emotional resilience.

The pink journal he leaves her symbolizes her transition into agency—an invitation to write her own story. Her reunion with Saint on Valentine’s Day, though born of yet another break-in, is no longer framed in crisis but as a moment of emotional convergence, marking her growth into someone who demands more than survival—she wants love, safety, and meaning, even if those things come from the most unexpected source.

Bentley

Bentley is a deeply unsettling antagonist whose presence lingers as a malevolent force throughout the narrative. As Hayley’s stepbrother, he wields both familial authority and social proximity as weapons, making his predatory behavior particularly insidious.

His gaslighting and lewd advances create a psychological minefield for Hayley, trapping her in a house that should be a sanctuary but instead becomes a site of ongoing trauma. Bentley represents a twisted embodiment of entitlement and impunity; he manipulates, threatens, and ultimately attempts to sexually assault Hayley, revealing the full extent of his depravity.

His role in the story is not merely to create external conflict but to amplify the internal war Hayley faces: the desire to be safe versus the reality of her vulnerability in a world where even her family cannot be trusted.

Bentley’s violence catalyzes one of the story’s most pivotal turning points—his death at Saint’s hands. This moment, while brutal, is framed less as an act of vengeance and more as one of protection, underlining the profound failure of all other structures to shield Hayley from harm.

Bentley’s narrative purpose is both literal and symbolic: he personifies the corrupt, dangerous familiarity that Hayley must escape to reclaim her life. His death is not only the climax of physical conflict but a metaphorical clearing of the old, oppressive order that kept Hayley trapped.

Even after his demise, the emotional and legal repercussions reverberate, forcing Hayley to confront the fallout without the comforting illusions of justice or closure. Bentley’s character, while vile, is crucial in revealing the deep-seated rot within Hayley’s family and in pushing her toward a path of self-liberation.

Hayley’s Mother

Hayley’s mother is a peripheral yet critical presence whose absence speaks volumes. Superficial, emotionally detached, and more invested in her tropical vacations than her daughter’s well-being, she embodies a chilling negligence.

Her failure is not dramatic or violent but chronic and insidious—she is the kind of parent who disappears when needed most, leaving Hayley to fend for herself in a household teeming with quiet violence. Even after Bentley’s death and the resulting trauma, her mother’s response is marked by a disturbing lack of empathy.

She does not rally around her daughter, seek answers, or express genuine concern. Instead, she treats the event as an inconvenient disruption, further reinforcing Hayley’s belief that her needs and pain are invisible to those who should care most.

This maternal neglect plays a foundational role in shaping Hayley’s vulnerability and her attraction to Saint. In a home devoid of emotional support, Hayley yearns for recognition, protection, and a sense of mattering.

Her mother’s indifference contrasts starkly with Saint’s possessive attention and validates her choice to turn toward someone society deems dangerous. Though not a central character in terms of page time, Hayley’s mother serves as a key emotional backdrop—her absence being just as impactful as any active cruelty.

She represents a generation or archetype of parental failure: those who turn away from uncomfortable truths and leave their children to pick up the pieces.

Dean (Hayley’s Stepfather)

Dean is a surprising outlier in the narrative. As Bentley’s father, one might expect him to adopt a position of denial, blame, or anger following his son’s death.

Instead, he reacts with unexpected sympathy and even relief, subtly acknowledging Bentley’s malevolence without ever stating it outright. His role is brief but impactful, hinting at the unspoken dysfunctions within the family and perhaps his own helplessness in controlling or reforming Bentley.

Dean’s muted response stands in contrast to Hayley’s mother’s callousness, suggesting a quieter, more complex internal struggle.

Though he doesn’t step into the role of protector or redeemer, Dean’s lack of hostility allows Hayley to navigate the aftermath of Bentley’s death with slightly less fear. His reaction adds a layer of ambiguity to the story’s moral landscape—it challenges readers to consider the unseen compromises adults make within broken families.

Dean’s character, while not redemptive, offers a flicker of human complexity in a cast often defined by extremes, and his subtle empathy provides a rare moment of subdued, if flawed, adult acknowledgment.

Themes

Abandonment and Emotional Neglect

Hayley and Saint are both shaped by profound emotional abandonment, which becomes the foundation of their attraction and the decisions they make. For Saint, abandonment is literal—his mother gave him up on the day he was born, and he aged out of the foster care system on Christmas, a day symbolic of warmth and family but experienced by him as a cruel reminder of disposability.

His homelessness and criminality are not only survival mechanisms but acts of rebellion against a world that has made him feel invisible. He believes society owes him nothing, and in turn, he owes it no allegiance or moral conformity.

Hayley, although materially privileged, endures a different kind of abandonment. Her mother and stepfather are absent during the holidays, prioritizing personal indulgence over her safety.

Worse still, her stepbrother Bentley represents a direct threat to her well-being, and her attempts to seek protection or affection from her mother are ignored or dismissed. The psychological impact of such neglect leaves Hayley yearning not for stability, but for acknowledgment and control.

When Saint reenters her life, she recognizes in him the same emotional fracture she experiences. Their connection, while intense and reckless, is fueled by an unspoken understanding of what it means to be cast aside and left to navigate life alone.

Their relationship becomes a form of protest and healing, however flawed, against the abandonment that has defined their pasts.

Power, Vulnerability, and Consent

Throughout Silent Night, the power dynamics between characters are charged with tension and complexity, especially in the way they oscillate between control and submission. Hayley’s interactions with Saint are marked by her willingness to explore vulnerability, not out of coercion but as a response to the rare feeling of being seen and desired on her own terms.

In contrast, Bentley’s presence exemplifies coercive power—the kind that uses emotional manipulation and the threat of violence to dominate. When Bentley attempts to sexually assault Hayley, the violation of consent is absolute and terrifying.

This incident is a stark reminder of the danger that exists within the family structures meant to offer protection. By comparison, Saint—despite being a criminal and a drifter—offers Hayley a paradoxical form of safety.

Their sexual encounters are laced with risk but grounded in mutual recognition of past wounds. Saint, for all his roughness, never crosses Hayley’s boundaries without invitation.

His control is performative, a response to her expressed desire rather than a disregard for it. This juxtaposition underscores how true consent is not just about physical safety, but emotional presence and respect.

Vulnerability in the story becomes a shared language, one that Hayley and Saint use to reclaim agency in a world that has repeatedly tried to strip them of it.

Crime, Morality, and Survival

The story challenges traditional notions of morality through Saint’s characterization as both a criminal and a protector. His life of theft is portrayed not as a purely malicious endeavor but as a logical, almost calculated response to systemic failure.

He steals from the rich not for luxury, but as an act of necessity and disdain. The dagger he takes from Hayley’s home years earlier is not just an object—it marks his first intentional step into a life of targeted theft, guided by a belief that those with abundance will not miss what they lose.

Hayley’s complicity in Saint’s crimes complicates the moral landscape even further. Her decisions are not based on right or wrong in a legal sense, but on emotional resonance and personal loyalty.

When she chooses to protect Saint after Bentley’s death, the moral equation is no longer about justice in its institutional form—it’s about survival and self-determination. The narrative refuses to simplify good and evil, instead presenting a world where crime becomes a language of survival for those who’ve been systematically ignored or abused.

Saint and Hayley’s moral codes are deeply personal, shaped more by experience than ideology, which makes their actions both justifiable and troubling. Their story suggests that in a world of broken systems, morality may be less about rules and more about who you are willing to protect and why.

Desire and Emotional Dependency

The relationship between Saint and Hayley is driven by intense desire, but what sustains it is an emotional dependency that borders on obsession. From the moment they reunite, their interactions are charged with sexual chemistry, yet it’s clear that physical desire is merely the entry point into something more complex.

Saint is captivated not just by Hayley’s beauty, but by her capacity to make him feel grounded and acknowledged. For someone who has lived in the shadows of society, this recognition is profoundly addictive.

Hayley, too, becomes increasingly dependent on Saint, not just for his physical presence but for the emotional escape he offers from her bleak domestic life. The secrecy of their relationship amplifies its intensity—everything becomes heightened because it exists outside the bounds of normalcy.

However, this dependency is not entirely romantic. It carries undertones of instability, where both characters use each other as emotional anchors in the absence of healthier support systems.

Their desire is not born of freedom but necessity, a way to affirm their worth through each other’s eyes. The final act, where Saint returns to Hayley and commits to a new life, solidifies how deeply their need for connection has evolved into something that feels redemptive, even if it remains haunted by their pasts.

Their love is not an escape from reality, but a shared attempt to build something real within it.

Identity and Transformation

Silent Night is fundamentally a story about transformation—how trauma, connection, and choice shape identity over time. Both Saint and Hayley begin the story as fragmented individuals, defined by past wounds and present circumstances.

Saint identifies as a thief, a reject, a man who belongs nowhere. His identity is rooted in detachment, and his belief that he cannot be anything else.

But Hayley disrupts that self-perception. Through her, he experiences the possibility of change—not because she saves him, but because she sees him as something more than the roles he has internalized.

For Hayley, the journey is similar. She starts as a young woman trapped in a house of silent violence, emotionally stunted by a mother who refuses to care and a stepbrother who poses a threat.

Her identity is initially reactive—she accommodates, endures, and survives. Yet through her interactions with Saint, she begins to act with intention.

She makes choices that center her own safety, desire, and agency, even when those choices defy societal norms. The culmination of their transformation is not in a grand gesture but in the quiet act of choosing to stay—Saint choosing permanence, and Hayley choosing hope.

Their growth is messy and incomplete, but it’s rooted in the idea that identity is not fixed. It can evolve, especially when someone dares to see you differently than the world has always seen you.

In this way, the story offers a dark but sincere testament to the human capacity for reinvention.