Sister Snake Summary, Characters and Themes

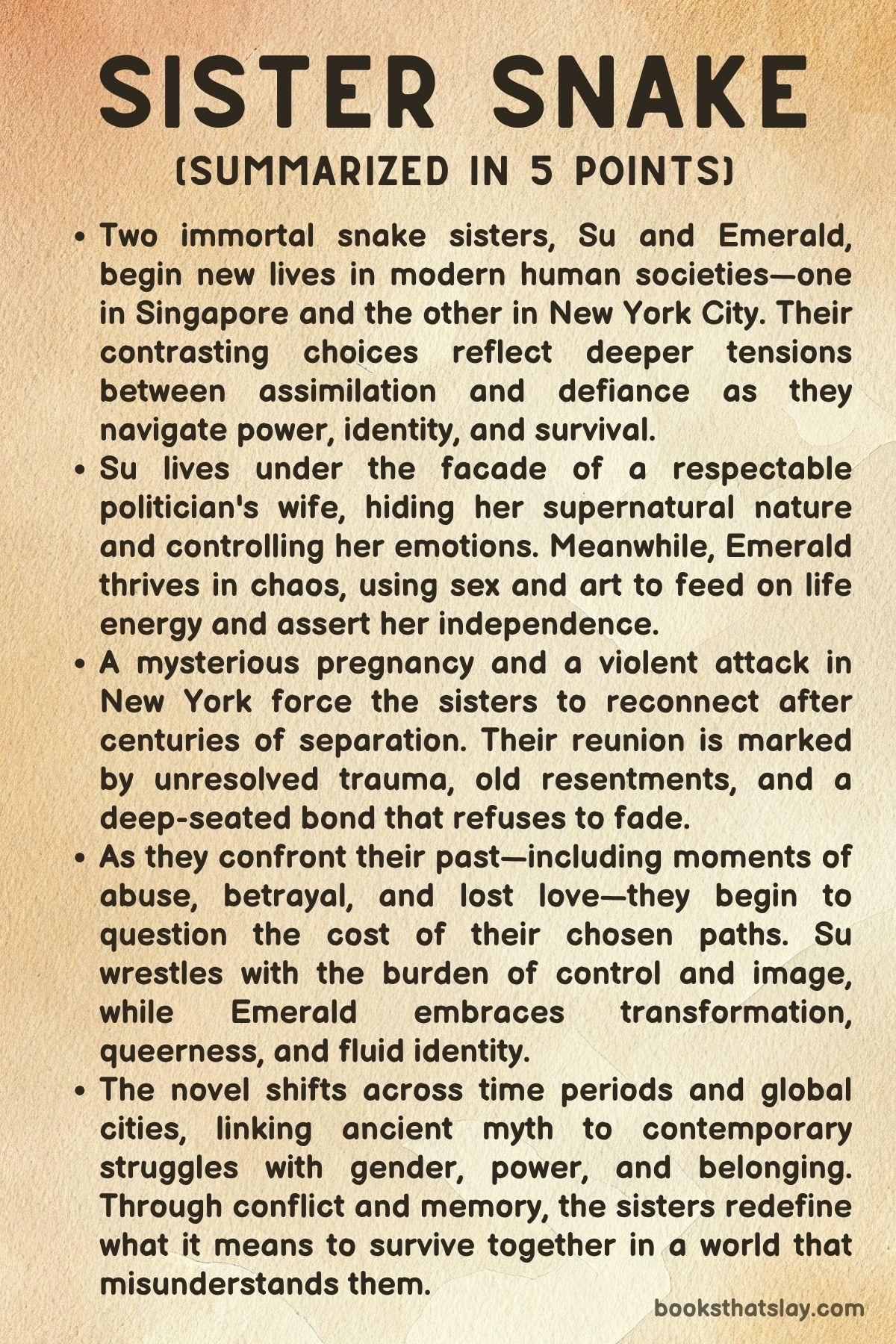

Sister Snake by Amanda Lee Koe is a bold, genre-bending novel that reimagines Chinese mythology in the context of contemporary gender politics, migration, and queer identity. At its heart are two immortal serpent sisters—Su and Emerald—who have lived for centuries by shedding their skins and adapting to new times, places, and expectations.

The novel takes readers from the glitz of New York to the rigid order of Singapore, tracing the sisters’ evolving relationship and opposing philosophies. Through allegory and rich storytelling, Koe crafts a narrative that explores what it means to live authentically, love defiantly, and survive in a world that demands masks and punishments for being different.

Summary

Sister Snake opens in the bustling metropolis of New York City, where Emerald—the younger, more impulsive of the two serpent sisters—makes a living by siphoning qi, or life force, from wealthy men she seduces. Her latest target, Giovanni, is a married art-world libertine who views Emerald as an exotic conquest rather than a person.

Beneath the surface of flirtation lies a scathing critique of race, power, and fetishization. When Giovanni sexually assaults her, Emerald retaliates by attacking him in her snake form.

Though she escapes thanks to an unexpected alliance with Central Park’s legendary sewer alligators, she is left wounded and barely alive. Her queer roommate Bartek rescues her, accepting her true nature without fear.

His friendship offers Emerald a rare moment of safety and affirmation, a chosen family in a world that marginalizes her.

Meanwhile, her older sister Su lives across the world in Singapore, posing as a perfect politician’s wife. She has carved out a life of high respectability and restraint, believing that assimilation and conformity are necessary for survival.

Su has suppressed her serpent nature, refraining from feeding or shedding her skin for decades. Her carefully constructed world begins to crack when a pregnancy test comes back positive—an impossibility for her kind.

Haunted by trauma from centuries past, Su grapples with the shocking revelation. Seeing Emerald’s near-death experience on the news propels Su to fly to New York.

Her decision is not rooted in logic but in the unbreakable bond between the sisters, who have not seen each other for years.

Once in New York, Su finds Giovanni in a hospital and finishes what Emerald started, feeding on his qi until he dies. This act marks Su’s reawakening to her true identity.

Returning to Singapore, she reenters her old life with new fire, blending her snake self with her public persona. Yet, the scars of assimilation remain, and her internal conflict deepens.

In “Apex Predator Femme Queen,” the narrative flashes back to the sisters’ past lives, including a failed cohabitation in Victorian England. There, Su embraced colonial safety while Emerald fled, seeking revolutionary love in India—only to lose her lover to violence.

In the present, the sisters reunite awkwardly in Brooklyn, where Su invites Emerald to visit Singapore. Against her better judgment, Emerald agrees, driven by love she won’t admit.

Bartek travels with her, charmed and frightened by Su’s polished façade. During their stay, Su kills Bartek after he inadvertently reminds her of her serpentine nature.

The act is both confession and suppression, showcasing Su’s fractured psyche.

Back in Singapore, Su visits a maternity clinic, where an ultrasound reveals that her child is a snake. Overcome with dread and alienation, she schedules an abortion but finds little comfort.

At a tense family dinner, Emerald confronts Paul—Su’s husband and a conservative politician—for his transphobic policies, sparking a dramatic confrontation. Later, Emerald finds companionship with Tik, Su’s bodyguard, and the two share a moment of tenderness.

Tik’s identity as a queer woman in uniform echoes Emerald’s own challenges with visibility and acceptance.

Their bond deepens when Emerald leads Su to a secret jungle sanctuary. There, the sisters briefly embrace their full serpent forms, reliving ancient unity.

But the moment collapses under the weight of their differences. Su’s desire for order and Emerald’s hunger for freedom cannot coexist.

The conflict intensifies when Emerald learns that Su killed Bartek. The betrayal severs their fragile reunion.

Still, Su reveals her pregnancy to Emerald, hoping it might restore their connection. Instead, Emerald calls her a monster and storms off.

She flees into the wild, spiraling into a destructive trance. Meanwhile, Su decides to keep the baby and begins to shed her socially imposed skin.

When Emerald returns to retrieve her belongings, the sisters remain estranged, broken by too much pain and too little understanding.

In the climactic arc, Emerald decides to leave Singapore but first helps Tik reconcile with her estranged lover Ploy. At Club Nana, she is poisoned by a black-magic concoction and begins transforming into her naga form.

Ploy and Tik care for her, summoning a Taoist healer who declares her a yaojing—a dangerous spirit. As her transformation escalates, Su appears, performing an ancient qi ritual to stabilize Emerald.

The ritual fails when Emerald, overwhelmed, bites her sister.

Su wakes in a hospital where her baby has been forcefully aborted under Paul’s orders. Furious and grieving, she sheds her human disguise, murders the doctor, and storms Parliament.

Paul is giving a speech extolling traditional values, and Su slaughters the political elite, including him, when he refuses to accept her truth. Emerald, having regained strength, helps Su escape.

Tik smuggles them away, eventually releasing them in their snake forms near Changi Beach.

The final epilogue offers a poetic denouement. In hiding near Jingci Temple, the sisters spend the winter healing.

When spring arrives, Emerald ventures out, drawn by the scent of candied haws. She meets a street vendor who is more than he seems—another supernatural being.

Her spontaneous joy and acceptance of both her humanity and her mythic origins signal a new chapter. The story ends with her laughing into the wind, sensing the jasmine scent that has always symbolized Su.

Their love endures—not perfect, but eternal.

Sister Snake is ultimately a story of transformation—not just in body, but in selfhood, relationships, and the reclamation of identity. It portrays the complexities of being queer, immigrant, feminine, and mythic in a world bent on erasure.

Through cycles of betrayal and reunion, Su and Emerald learn to choose their truths, even if the cost is everything else.

Characters

Emerald

Emerald, the green snake, is a volatile, passionate embodiment of rebellion, survival, and subversion. Her existence in Sister Snake is defined by her refusal to conform—whether to societal expectations, moral binaries, or the limits of human identity.

Living in New York City as a sugar baby, she uses her beauty and seduction not merely for survival but as weapons of autonomy. Emerald’s feeding on human qi is not simply vampiric but symbolic: she thrives off the same systems that objectify and exploit her, subverting them from within.

Her interactions with Giovanni reflect a scathing critique of racial fetishization and male dominance; his physical violation of her prompts a transformation into her serpent form, a moment both of righteous fury and traumatic consequence. After being shot by the police, her rescue by sewer alligators signals how society discards and misjudges the “monstrous,” while her friendship with Bartek offers a rare safe space where freakishness and vulnerability coexist without judgment.

Emerald’s emotional complexity is revealed through flashbacks and present-day pain. Her past—spanning colonial England to revolutionary India—demonstrates her persistent yearning for freedom and love, especially in the queer, doomed relationship with Rani.

Her flirtation and emotional connection with Tik is similarly tender, rooted in mutual recognition of outsider status. Emerald is constantly navigating grief, betrayal, desire, and hope.

The death of Bartek devastates her, especially after learning Su was responsible. Her ultimate choice to escape, help others (like reuniting Tik and Ploy), and embrace her naga identity shows transformation not just in the mythic sense, but in terms of radical self-acceptance.

By the novel’s end, her spontaneous laughter, drawn by the scent of candied haws, encapsulates the joy of fully embracing a self both human and otherworldly—alive, wounded, and defiant.

Su

Su, the white snake, represents the opposite pole of Emerald’s defiant visibility: a character marked by restraint, control, and the desperate need to assimilate. Living in Singapore as the wife of a conservative minister, Su has spent centuries perfecting the performance of womanhood, domesticity, and quiet excellence.

Her abstention from consuming qi or shedding her skin is a metaphorical self-imprisonment—a denial of her nature to maintain societal approval. This conformity stems not from apathy but from deep trauma: a brutal mating ritual centuries ago left her physically and emotionally scarred, and she has spent her immortal life hiding that wound beneath layers of elegance and order.

Her pregnancy—which should be impossible—forces a confrontation with that past, revealing a woman at war with her identity, shame, and a society that demands perfection and submission.

Su’s complexity is heightened by her capacity for both cruelty and care. She murders Bartek in a sudden, terrifying act driven by fear and repression, then hides the truth even from herself.

Her dynamic with Emerald is layered with jealousy, love, protectiveness, and guilt. Su sees herself as Emerald’s caretaker and cleaner, as seen in her execution of Giovanni, but also resents Emerald’s chaos and freedom.

When her husband orchestrates a forced abortion, denying her autonomy and rejecting her truth, Su finally sheds her mask. Her rampage through Parliament—killing Paul and his allies—marks a dramatic reclamation of power.

Yet, even in vengeance, Su is not monstrous; she is a woman finally choosing to live on her own terms, rejecting the roles society forced upon her. Her epilogue, resting and healing with Emerald, signifies a return not just to sisterhood but to a fuller selfhood—one unburdened by performance, steeped in quiet rage, and open to renewal.

Bartek

Bartek is a grounding force in Sister Snake, offering Emerald a sense of chosen family and unconditional acceptance. Queer, eccentric, and empathetic, Bartek provides a space where Emerald can be her true self—unmasked, unashamed, even when feeding on raw eggs.

Their relationship transcends the transactional or performative; he treats her not as a spectacle but as a complex being. His humor and warmth offer contrast to the cold, oppressive environments that define much of Emerald and Su’s lives.

Bartek’s tragic death at Su’s hands serves as both narrative turning point and moral rupture. His murder represents the cost of repression and the dangers of denying one’s true self.

His memory lingers, shaping Emerald’s grief and catalyzing her eventual rejection of Su’s worldview.

Tik

Tik, the stoic and principled bodyguard, is a quietly profound character whose arc embodies the struggle for dignity in a society that fears queerness, difference, and emotional openness. Tasked with protecting Su, Tik initially appears loyal and detached.

However, her interactions with Emerald unlock a different side of her: empathetic, playful, and deeply human. Tik’s queerness—barely tolerated within her institutional role—creates a point of kinship with Emerald.

Their flirtation becomes a space of honesty and recognition. Tik also serves as a moral compass in the later stages of the novel, choosing to protect Emerald rather than betray her, despite knowing the consequences.

Her decision to help the naga sisters escape Parliament marks a quiet rebellion against the state she once served and affirms her loyalty not to authority but to truth and love. Through Tik, the novel explores how institutional power can suffocate the self—and how small acts of compassion can rewrite legacies.

Paul

Paul is a symbol of conservative dominance, patriarchal authority, and political hypocrisy. As Su’s husband and a government minister promoting “family values,” Paul embodies the very systems that demand women—especially immigrant or queer-coded women—suppress their identities for survival.

He is affable and persuasive in public, but at home, his disregard for Su’s truth is chilling. His refusal to believe in her pregnancy, his dismissal of parthenogenesis, and his orchestration of her forced abortion are violations both bodily and existential.

His final act of declaring love to Su before she kills him underscores the hollowness of his affection—he loves the performance, not the woman. Paul’s arc ends not with redemption but with exposure: a man undone by the very monstrosity he sought to contain, a victim of the truth he refused to accept.

Giovanni

Giovanni, the art-collecting playboy, is less a fully realized character than a narrative tool to expose the intersection of racism, misogyny, and fetishization. His treatment of Emerald as an exotic, submissive object reflects broader societal dehumanization of Asian femininity.

He believes himself enlightened and charming, but his assault on Emerald reveals a predatory entitlement. His near-death and eventual demise—first at Emerald’s fangs, then at Su’s hands—signal a symbolic retribution against colonial, capitalist exploitation.

Giovanni’s arc emphasizes that danger often comes not from the supernatural, but from the mundane violence of unchecked privilege.

Ploy and Uncle Lu

Though supporting characters, Ploy and Uncle Lu offer symbolic significance. Ploy’s club is a haven for queer joy, community, and survival—an environment where people like Emerald and Tik can exist freely.

Her role in aiding Emerald’s healing emphasizes solidarity across gender and identity lines. Uncle Lu, with his Taoist wisdom and mysticism, marks the boundary between tradition and modernity.

His recognition of Emerald as a yaojing—not with fear but clarity—helps define her hybrid identity. Both characters serve to support the narrative’s central theme: that identity is fluid, multifaceted, and often only visible to those willing to see with compassion.

Themes

Gender, Identity, and the Fluidity of Self

In Sister Snake, gender and identity are portrayed not as fixed traits but as fluid, performative constructs that evolve across time and context. Emerald and Su, immortal snake spirits who take on human forms, embody different expressions of femininity and womanhood.

Emerald’s identity is fiercely queer, unapologetically visible, and sensually assertive—she expresses herself through clothing, flirtation, and vulnerability, thriving in the chaos of modern New York. Su, by contrast, adopts the mannerisms and constraints of traditional femininity to survive in Singapore’s conservative elite.

Her life as a politician’s wife is governed by routines, aesthetic discipline, and societal approval, even as it conflicts with her inner desires. The contrast between the sisters shows how gender expression is often shaped by environment and survival tactics rather than innate truth.

The story refuses to reduce their identities to binaries; instead, it emphasizes the performance, adaptation, and self-determination involved in choosing how to exist. Whether Emerald is feeding on eggs in front of a queer friend or Su is silently suffering through an ultrasound showing a snake-like fetus, both face the tension between external expectations and internal truth.

Their shared immortality only amplifies the stakes: centuries of repression, experimentation, and recalibration have not led to a settled self but rather a continuous negotiation of visibility, vulnerability, and transformation. The novel thus critiques gender essentialism, instead advocating for identities that are hybrid, transitional, and responsive to both trauma and longing.

Sisterhood as Intimacy, Betrayal, and Reconciliation

The relationship between Su and Emerald stands at the emotional core of Sister Snake, encompassing deep devotion, ideological divergence, and repeated ruptures. Their connection is not only biological but spiritual, formed over centuries of mythological existence and human performance.

Their bond is marked by cycles of closeness and distance, often reflecting larger questions about loyalty, love, and the difficulty of sustaining intimacy when values and desires shift. Emerald craves authentic connection and expressive relationships, while Su retreats into silence and respectability, believing that invisibility offers protection.

This divergence creates resentment: Emerald sees Su’s compliance as cowardice, while Su views Emerald’s rebellion as recklessness. Their dynamic reaches breaking points multiple times—through acts of violence, secrets kept, and emotional betrayals like Su killing Bartek.

Yet even in their worst moments, a yearning persists. When Su helps Emerald heal after a poisoning or when Emerald protects Su after her massacre in Parliament, their love resurfaces, no longer as romanticized sisterhood but as something rawer and harder to define.

Their reconciliation is not framed as perfect harmony but as a mutual recognition of pain and loyalty that transcends ideological difference. Theirs is a relationship forged through myth, disrupted by human failings, and reconstructed through difficult, sometimes destructive acts of care.

In charting their fractured journey, the novel speaks to how chosen family and sibling love can be both a refuge and a battlefield—at once tender and brutal, conditional and eternal.

Capitalism, Fetishization, and Commodification of the Body

Across its global settings, Sister Snake critiques how capitalism commodifies not only labor but bodies, especially those of women and marginalized beings. Emerald’s life as a sugar baby in New York positions her as both agent and object in a transactional world.

She survives by feeding off men like Giovanni, who see her as an exotic accessory and treat her desire and pain as consumable fantasies. Giovanni’s racial fetishization, financial dominance, and eventual sexual violence underscore the exploitative dynamics that capitalism sustains, particularly when it intersects with patriarchy and racism.

Emerald’s survival strategy, though empowering in its subversion, never offers real freedom—her body is always a site of exchange, extraction, and danger. In Singapore, Su uses luxury consumerism to anesthetize her emotional turmoil.

High fashion, curated domesticity, and polite public appearances become armor against the mess of her true self. Her careful cultivation of status mirrors how respectability politics seduce those seeking safety within oppressive systems.

Even her pregnancy becomes a commodity—her husband Paul uses it as political capital while denying her bodily autonomy. These twin narratives expose how capitalist structures infiltrate the most intimate spheres, transforming desire, survival, and even grief into marketable or disposable entities.

Through the sisters’ contrasting choices, the novel questions whether agency can ever be fully realized within a system that profits from one’s pain, beauty, or obedience, and whether the body can ever escape being a currency in a world structured by dominance.

Queerness, Desire, and Chosen Family

The novel situates queerness not as a subplot but as a fundamental framework for understanding love, belonging, and resistance. Emerald’s queer identity is reflected not only in her desires but in how she navigates the world—with boldness, complexity, and a constant need to negotiate space.

Her relationship with Bartek is platonic but deeply intimate, characterized by mutual recognition of difference and care. Their shared outsider status forms a sanctuary, a chosen kinship more sustaining than biological ties.

Her brief romantic connection with Tik also illuminates how queerness can be a bridge between marginalized experiences, offering tenderness and mutual understanding in a hostile world. Meanwhile, Su’s queerness is more suppressed—buried beneath performance, shame, and violence.

Her killing of Bartek is not just monstrous but symbolic of how internalized self-hatred and repression can devastate relationships and self-worth. The story critiques respectability politics and the demand to hide or neutralize queerness to survive.

Yet it also celebrates queer joy, resilience, and love—especially in the novel’s quieter moments of connection, like Emerald’s kiss with Tik or her choice to help Ploy and Tik reunite. Queerness in Sister Snake is not merely sexual orientation; it is a radical orientation toward care, chosen kin, and ways of living that defy conventional morality.

The novel ultimately frames queer love as sacred, necessary, and sometimes the only form of truth available in a world that rewards denial.

The Violence and Cost of Assimilation

Su’s trajectory across Sister Snake illustrates the insidious cost of assimilation, especially for beings and people who live on the margins. Her commitment to appearing human—refined, controlled, respectable—demands relentless suppression of her true self.

Whether abstaining from qi consumption, concealing her trauma, or marrying into political power, Su constructs a life that requires constant performance. Her choice to abort—or later, to keep—a supernatural pregnancy symbolizes this war within: the desire to conform clashing with the need to reclaim identity.

Su’s eventual breakdown, culminating in violence at Parliament, reveals how the pressure to assimilate can lead not to safety but to implosion. Her suffering is compounded by a society that venerates motherhood while denying her bodily agency, celebrates her image while rejecting her truth.

The novel critiques how assimilation promises belonging but delivers erasure. Su’s story warns that survival through conformity often results in spiritual death.

In contrast, Emerald’s resistance to fitting in—her embrace of queerness, vulnerability, and expression—while risky and painful, offers a path toward authenticity. The tension between the sisters reflects a broader commentary on immigrant, queer, and mythic identities navigating dominant cultural expectations.

The novel offers no easy resolution but instead highlights how survival strategies can become prisons, and how the cost of acceptance often includes betrayal of the self.

Power, Violence, and Reclamation of the Mythic Self

Throughout Sister Snake, power is portrayed not as static or inherently redemptive but as something shaped by context, identity, and memory. Both sisters possess supernatural abilities—shape-shifting, qi-feeding, long lifespans—but the use of these powers is heavily constrained by the human world they inhabit.

Emerald’s attack on Giovanni and Su’s eventual massacre at Parliament are not just acts of rage but expressions of long-denied power. These moments of violence are framed with moral ambiguity; they are both transgressive and cathartic, demanding a reconsideration of what justice looks like for beings who have endured centuries of erasure and harm.

The transformation into naga form is especially symbolic. It marks a rejection of shame and an embrace of a heritage that has been suppressed or hidden for safety.

For Su, her shedding of human form at Parliament is not just rebellion—it is truth made visible, a rupture of political and personal deception. Emerald’s final scene, drawn to a supernatural vendor by smell and whim, reveals how power, when no longer denied or feared, can become joyous and generative.

The novel suggests that reclaiming one’s mythic self is an act of spiritual survival, a declaration that being powerful and being loved are not mutually exclusive. This theme offers a radical vision of empowerment—not as dominance but as authenticity, not as vengeance but as visibility, even if that visibility comes at a cost.