Sisters in Science Summary and Analysis

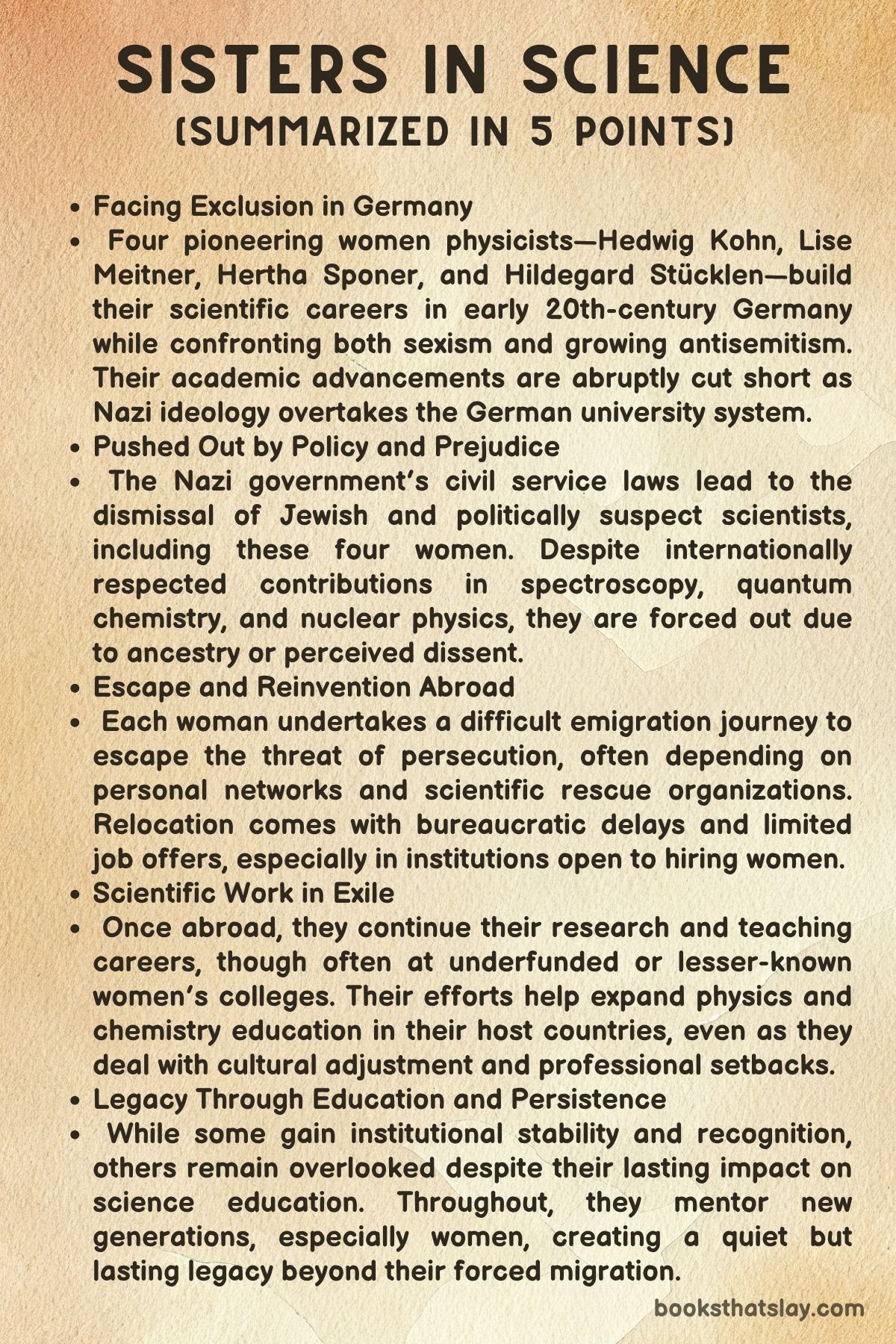

Sisters in Science by Olivia Campbell is a book that traces the lives and scientific legacies of four brilliant women physicists—Hedwig Kohn, Lise Meitner, Hertha Sponer, and Hildegard Stücklen. These women battled systemic sexism, rising fascism, and the upheaval of global war to preserve their careers and integrity.

This book is more than a history of science—it’s a testament to the courage and perseverance of women whose intellects were dismissed and whose identities made them targets under Nazi rule. By following their academic journeys, escapes, and eventual impact on global science, Campbell offers a powerful reflection on resilience and recognition in the face of institutional betrayal.

Summary

Sisters in Science begins with the story of Hedwig Kohn, a determined physicist born in 1887 in Breslau, Germany. Raised in a progressive Jewish household, Hedwig pursued education at a time when women were discouraged from entering scientific fields.

Though initially barred from formal university enrollment, she audited classes until women were formally admitted, eventually earning her PhD in 1913. Her research focused on spectroscopy—the study of interactions between matter and electromagnetic radiation.

Under the mentorship of Otto Lummer and Rudolf Ladenburg, she produced groundbreaking work on the emission of metals in flames. This not only supported key scientific laws but had industrial applications in lighting technology.

Despite her achievements, she struggled for decades to obtain habilitation, the certification required to teach at the university level, due to institutional sexism. She finally earned this credential in 1930, becoming only the third woman in Germany to do so in physics.

The rise of the Nazi regime in 1933 changed everything. The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service targeted Jewish academics, leading to the dismissal of over a thousand university staff, including Hedwig.

Her distinguished record was disregarded because of her heritage—she was deemed “non-Aryan” and stripped of her position. She began a desperate years-long search for refuge and employment abroad, reaching out to aid organizations, colleagues, and former mentors.

Ladenburg, then at Princeton, was instrumental in advocating for her, listing her as a top candidate for rescue. However, gender bias persisted even among sympathetic institutions, limiting her opportunities for relocation and employment.

While Hedwig’s struggle played out, other women physicists like Lise Meitner, Hertha Sponer, and Hildegard Stücklen were navigating their own battles against sexism and political oppression. Lise Meitner, a physicist working alongside Otto Hahn, rose to prominence through her pioneering work in nuclear chemistry at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin.

Known for her meticulous lab protocols and rigorous experiments, she was eventually appointed head of her own department. Lise participated in intellectual circles filled with prominent scientists like Einstein and Bohr.

She was known for her sharp mind and modest demeanor, and her informal scientific discussions helped challenge hierarchical norms in academic institutions.

Hertha Sponer’s career took her from Göttingen to Duke University. She contributed critical advancements to spectroscopy and molecular physics, particularly through the development of the Birge–Sponer method.

Like Lise, Hertha’s path was marked by reliance on male advocates and institutional resistance. Although the Weimar Republic introduced progressive constitutional promises of gender equality, actual conditions lagged behind.

Female scientists needed male patrons, received less pay, and held lower-ranking titles. Still, Hertha’s intellectual prowess and persistence led her to a permanent academic role in the United States, where she became a central figure in supporting fellow exiled women scientists.

As the Nazi regime solidified its grip on Germany, the fate of Jewish scientists—especially women—grew more precarious. Lise Meitner, of Jewish ancestry, lost her professorship despite her contributions to nuclear research.

Franck, one of her closest allies, resigned in protest, a rare but notable act of solidarity. Still, Lise’s career was derailed, and she sought refuge in Sweden.

Meanwhile, Hedwig’s chances of escape were narrowing. The bureaucratic barriers were enormous.

Despite her academic reputation, the U. S. immigration quota system and widespread sexism worked against her. Organizations like the International Federation of University Women (IFUW), the American Association of University Women (AAUW), and the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars made efforts, but the systemic exclusion of women from support programs was stark—of thousands of applicants, only a handful of women were helped.

Ultimately, it was the coordinated determination of her scientific network that saved Hedwig. Lise Meitner advocated on her behalf, while Karin Kock from IFUW helped secure a temporary Swedish visa.

Ladenburg launched a unique campaign by sending simultaneous requests to multiple American institutions, a strategy that bypassed the usual bureaucratic bottlenecks. Though responses varied, institutions like Sweet Briar and Wellesley offered her tentative positions.

Hertha Sponer, working at the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina, directly appealed to administrators to provide Hedwig a temporary appointment. After intense lobbying and the promise of external financial support, UNC agreed.

In July 1940, Hedwig fled Germany with her scientific equipment and a sliver of hope.

Hedwig’s arrival in Sweden brought some peace. She spent time with Lise, talking about physics and reclaiming part of her professional identity.

But she still needed to reach the United States for long-term safety. In October, she began a long and difficult journey via the Soviet Union and Japan to America.

She arrived in Chicago exhausted and ill but was taken in by friends like Rudolf Ladenburg and Hertha Sponer. She recovered and eventually started teaching in North Carolina, later working at Wellesley College.

Her classes evolved from introductory lessons to advanced physics courses, and she mentored many students while continuing her research.

Not all Jewish women scientists were as fortunate. Many were denied visas or employment due to misogyny and racial laws.

Marie Anna Schirmann and Leonore Brecher, among others, were denied habilitation and lacked the credentials to escape. They perished in ghettos or extermination camps, victims not just of antisemitism, but of global indifference to women’s intellectual lives.

Even brilliant scientists with strong letters of recommendation and substantial contributions were often turned away, their lives ending in obscurity.

Those who survived formed close professional and emotional bonds in exile. Hedwig, Hertha, and Hildegard Stücklen found ways to continue their work, supporting one another in the process.

Hertha’s lab at Duke became a seasonal gathering place for research and camaraderie. She later married physicist James Franck, one of the few men who had consistently supported women in science.

Their union was a rare point of personal happiness amid a backdrop of professional trauma and displacement.

Postwar, Lise Meitner toured the United States, delivering lectures and reflecting on her scientific and personal journey. Her bitterness toward Otto Hahn, who had benefited from her work and remained compliant under the Nazi regime, was evident in her correspondence.

Max von Laue eventually acknowledged his moral shortcomings, but many others remained unrepentant.

In their later years, these women continued to teach, write, and mentor. Their impact on science education, especially for young women in the United States, was significant.

They built not just careers but a legacy of intellectual courage and sisterhood. The history of Sisters in Science is one of survival, achievement, and collective strength in the face of some of the darkest forces of the 20th century.

Their story endures as a testament to what is possible when women support each other in the pursuit of knowledge and justice.

Key People

Lise Meitner

Lise Meitner emerges as both a scientific genius and a tragic figure whose brilliance was persistently overshadowed by systemic gender and racial bias. Born into a Jewish family but raised Protestant, she established herself as a nuclear physicist in a male-dominated world.

She collaborated with Otto Hahn in Germany and played a pivotal role in the discovery of nuclear fission. Despite her crucial theoretical work, she was excluded from the 1944 Nobel Prize awarded solely to Hahn—an exclusion that became symbolic of how women were written out of scientific history.

Her escape from Nazi Austria was perilous and marked by bureaucratic evasions and the support of loyal male colleagues. In exile, Meitner continued her research in Sweden, although her Swedish colleagues offered her poor facilities and little regard.

Later, she moved to the U.K., where she continued advocating for science and ethics but was never granted the institutional prestige that her scientific contributions warranted. Her career reflects the dual challenge of being a woman and an ethnic outsider in European science—recognized too late and often with misgivings.

She remained humble despite belated honors, rejecting labels like “mother of the atom bomb,” which conflicted with her humanitarian ideals.

Hedwig Kohn

Hedwig Kohn’s story is one of methodical brilliance, personal resilience, and understated transformation. A master of spectroscopy, she built her reputation through rigorous experimentation and teaching at the University of Breslau.

Her scientific contributions, particularly in the measurement of light intensity and atomic spectra, were substantial and foundational. However, as a Jewish woman, she was swiftly ousted from her academic position by the Nazi racial laws.

Her journey to escape Nazi Germany was particularly harrowing—marked by numerous failed visa applications, long periods of professional limbo, and dependence on the slow-moving machinery of academic rescue networks. Unlike some of her contemporaries, she did not secure a position in elite institutions.

Instead, she rebuilt her career in American women’s colleges such as Wellesley and the Women’s College of the University of North Carolina. There, she not only resumed scientific work but also trained generations of women in physics, establishing respected laboratories despite scarce resources.

Kohn exemplified the transformative power of education and persistence. Her story is a testament to how scientific impact can flourish in nontraditional environments, and how exile, while tragic, can lead to new forms of intellectual legacy.

Hertha Sponer

Hertha Sponer occupies a unique space in the narrative as both a scientific trailblazer and a successful institutional builder. A German physicist and chemist, she made seminal contributions to molecular spectroscopy and quantum chemistry.

Initially collaborating with figures like James Franck, she brought German precision and rigor into her research. Her decision to emigrate to the U.S. before the full onset of Nazi terror enabled her to secure a more stable academic foothold than some of her peers.

She joined Duke University, where she became a pillar of its physics department, integrating modern research methods and fostering German-American scholarly collaboration. Sponer’s story differs in its relative stability and success, yet it also reveals the constraints imposed on even the most qualified women.

Though she achieved tenure and research distinction, her journey required continual negotiation of cultural and institutional skepticism toward female scientists. Sponer remained a committed educator, researcher, and mentor, helping shape U.S. science education during and after the war.

Her legacy lives in the institutions she strengthened and the students she mentored, underscoring her role not only as a survivor of exile but as a scientific architect in a new homeland.

Hildegard Stücklen

Hildegard Stücklen is perhaps the most understated among the quartet, yet her quiet strength and consistent contributions make her integral to the broader narrative. Specializing in gas discharge and spectroscopy, she built her career with meticulous research and practical teaching.

Unlike Meitner or Sponer, Stücklen’s path was not marked by fame or controversy but by a steady commitment to science under trying circumstances. She emigrated from Europe with little fanfare and took up positions at American liberal arts and women’s colleges, where she became a respected educator and researcher.

Her work was instrumental in sustaining advanced physics curricula in institutions often overlooked by the broader academic community. Stücklen’s legacy is one of constancy and quiet dedication—of preserving scientific rigor in settings that lacked prestige but served as havens for displaced intellectuals.

Her presence in these institutions ensured that women students encountered serious scientific education during an era when few other opportunities existed. Stücklen may not have been as celebrated or widely known, but her enduring commitment to both pedagogy and research reflects the essential role of less-publicized scientists in maintaining and transmitting knowledge across generations.

These character arcs, as woven together in Sisters in Science, do more than recount individual struggles. They collectively illustrate the structural forces—patriarchy, xenophobia, and war—that these women resisted and, in many ways, transcended.

Their lives form a constellation of brilliance that illuminated mid-20th-century science from the margins.

Themes

Systemic Barriers Against Women in Science

The experiences of Hedwig Kohn, Lise Meitner, Hertha Sponer, and Hildegard Stücklen reveal the entrenched gender discrimination that permeated early 20th-century scientific institutions. These women, despite demonstrating extraordinary academic capability and pioneering research, were frequently denied positions, fair compensation, and professional recognition because of their gender.

Hedwig Kohn was denied habilitation for years, an essential credential for university-level teaching in Germany, despite her significant contributions to spectroscopy. Lise Meitner, though instrumental in the discovery of nuclear fission, often took second place to her male colleagues in accolades and public acknowledgment.

Hertha Sponer and Hildegard Stücklen also encountered academic environments where male mentorship often substituted for formal opportunities, illustrating how women’s professional advancements were reliant not solely on merit but on navigating patriarchal gatekeeping. Even when legislation like the Weimar Constitution nominally offered equal rights, cultural and institutional inertia ensured that those promises were rarely fulfilled in practice.

This theme highlights not only the individual resilience of these scientists but also the persistent structural inequality that forced them to work twice as hard for half the recognition. Their successes were exceptions, not norms, achieved despite a system that routinely disregarded their intellectual worth.

The legacy they leave behind is not just scientific; it is also a historical record of resistance against erasure, a call to acknowledge and rectify the long-standing marginalization of women in the sciences.

Intellectual Integrity Versus Political Oppression

As fascism spread across Europe, many Jewish and politically liberal scientists faced moral dilemmas that tested their commitment to truth and ethical principles. Hedwig Kohn’s dismissal from her academic post in 1933 was not due to incompetence but rather to her Jewish heritage, as enforced by the Nazi regime’s racial laws.

Her case exemplifies how scientific merit was subordinated to ideological conformity. Similarly, Lise Meitner, despite having contributed significantly to Germany during World War I and becoming a leading nuclear physicist, was cast aside when Nazi policies no longer tolerated her ancestry.

Some of their colleagues, like James Franck, chose to resign in protest, but others, such as Otto Hahn, remained complicit or indifferent, continuing their work in a system built on exclusion and repression. The bureaucratic machinery of the Third Reich weaponized civil service laws to purge universities of Jews and dissidents, silencing some of the brightest minds in Europe.

This theme exposes the devastating consequences when political ideology is allowed to corrupt academic independence and moral responsibility. It reveals the tension between individual conscience and systemic pressures, asking what it means to stand for truth in a society that punishes it.

For the women scientists in Sisters in Science, exile and displacement became the price of integrity—a testament to how intellectual freedom can become both a liability and a lifeline under tyranny.

Exile, Displacement, and Scientific Survival

The narrative of these women scientists is also a chronicle of forced migration and the desperate quest for survival in a world increasingly hostile to both their identities and their intellectual work. Hedwig Kohn’s path from Nazi Germany to a position at a small American college was not a career move; it was a life-saving escape that took years of strategic pleading, paperwork, and advocacy from colleagues.

The emotional and physical toll of displacement was profound—exemplified by Hedwig collapsing upon arrival in Chicago—but it also marked the beginning of a painful rebirth. Lise Meitner, isolated in Sweden, faced professional irrelevance and personal loneliness, while others like Hertha Sponer and Hildegard Stücklen carved out new academic homes in the United States, often with limited resources and support.

These women did not just cross borders; they carried with them the burden of rebuilding careers in alien institutions with lingering xenophobia and misogyny. Yet, their presence in the U.S. transformed local academic landscapes.

They introduced new methods, mentored young women, and broadened the scope of scientific inquiry. This theme underscores the duality of exile: both as a form of erasure and as an unlikely avenue for transformation.

It also foregrounds the collective, transnational effort—by aid committees, fellow scholars, and women’s organizations—that preserved their legacies against all odds.

Scientific Sisterhood and Mutual Advocacy

While systemic sexism and political violence threatened their careers and lives, one of the most powerful counterforces in Sisters in Science is the community of women scientists who advocated for one another with unyielding persistence. Lise Meitner and Hertha Sponer did not merely share research interests with other women like Hedwig Kohn and Hildegard Stücklen—they provided practical lifelines.

Lise coordinated with the IFUW to secure Hedwig’s temporary Swedish visa. Hertha worked her academic connections at Duke and UNC to obtain real employment for her.

These actions were not symbolic; they were acts of salvation. At a time when mainstream institutions were slow to act—or outright indifferent—these women mobilized their social and professional networks to keep one another safe and scientifically active.

Theirs was not just solidarity of circumstance but of shared conviction that science must not be allowed to abandon its moral compass. The support extended beyond logistics: they offered emotional care, housed one another, created lab spaces, and co-authored papers.

This sisterhood turned moments of crisis into seeds of continuity. Their advocacy anticipated modern concepts of allyship and intersectional feminism.

It was this network that preserved lives and ideas during one of history’s darkest chapters, proving that science, often thought to be impersonal and isolated, can also be deeply communal and humanistic when shaped by those determined to uplift rather than exclude.

The Intergenerational Legacy of Scientific Women

Despite the upheavals of war, displacement, and systemic barriers, the enduring impact of the women portrayed in Sisters in Science is evident in the academic and cultural institutions they helped shape. Hedwig Kohn, though beginning her American academic career at a modest women’s college, mentored a generation of physics students and introduced advanced scientific curricula.

Hertha Sponer’s position at Duke became a rare permanent foothold for women in physics at the time, enabling her to become a role model and research leader. Even in exile, these scientists created environments that nurtured future generations, ensuring that the disciplines of spectroscopy, nuclear physics, and molecular chemistry would carry their mark.

Their contributions were not limited to technical research but extended to institutional development and educational reform, particularly in opening scientific pathways to women in the U. S.

At a time when women were largely excluded from science, their visibility and success offered inspiration and precedent. Furthermore, the ethical questions they posed through their resistance—about who gets to do science, under what conditions, and at what moral cost—continue to resonate in academic discourses today.

This legacy is neither accidental nor merely symbolic; it is deeply rooted in the lived experiences of women who saw science not as a solitary pursuit but as a platform for communal progress. Their stories remain essential not only to understanding the past but to envisioning a more inclusive future for science.