Slashed Beauties Summary, Characters and Themes

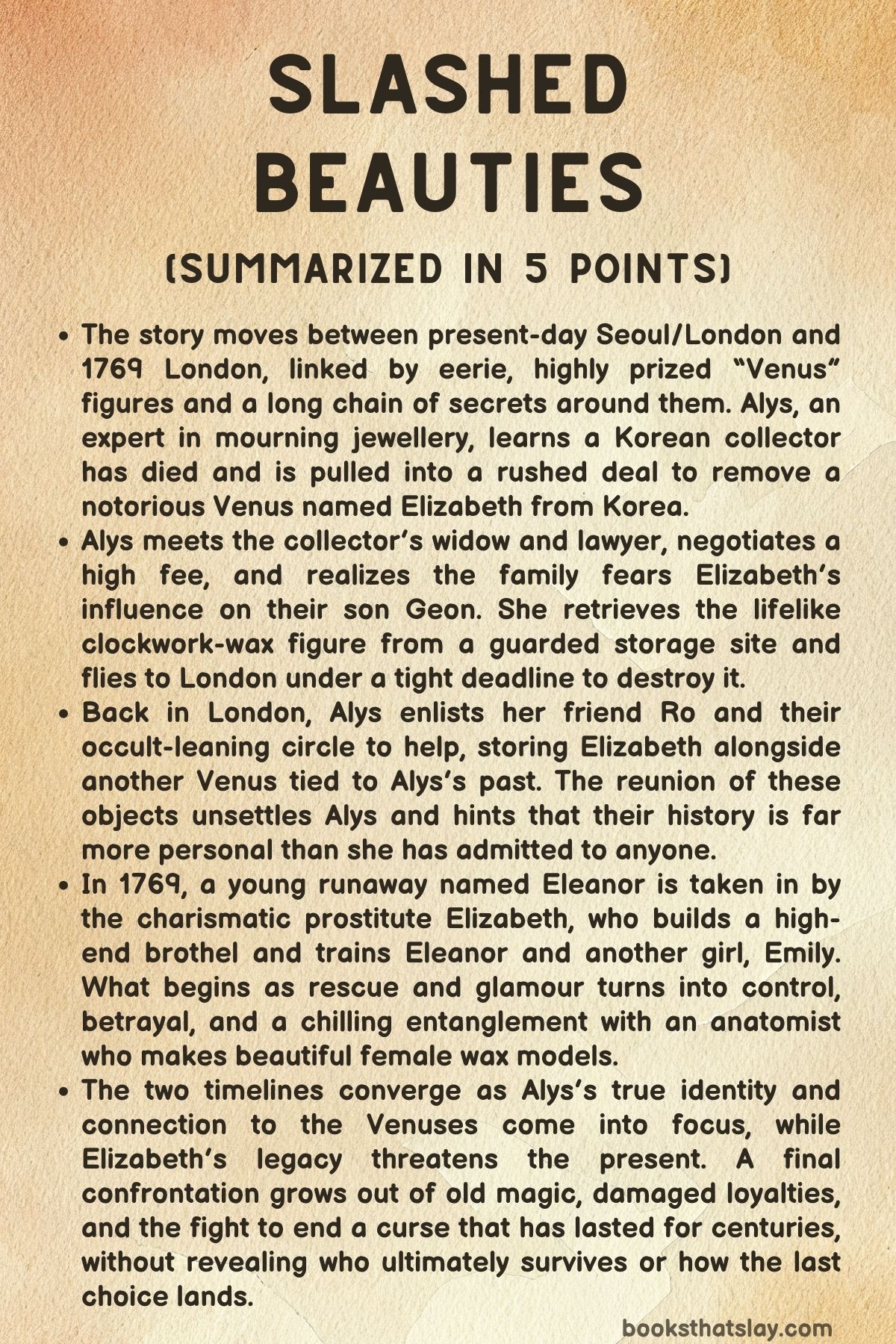

Slashed Beauties by A. Rushby is a gothic-leaning fantasy that moves between modern Seoul and London in 1769, using the trade of mourning jewellery and the eerie art of wax anatomical models to explore power, survival, and inheritance.

At its center is Alys, a sharp, secretive dealer whose expertise in hairwork hides a far stranger truth about her age and her past. The story circles two legendary “Venuses,” beautiful objects with a terrible history, and asks what it costs to outlive your own life—especially when others want to own the body you once had.

Summary

Alys lives in present-day Seoul, working as a specialist dealer in mourning jewellery, especially rare hairwork pieces. She is waiting for news that a wealthy collector, Mr Yoon, has died, because his death activates a private agreement she made with his widow.

When the confirmation arrives in the small hours, Alys sets herself in motion. Before meeting Mrs Yoon, she fulfills a client visit, delivering a Georgian hairwork brooch to Veronique, a severe, wealthy collector whose home is more gallery than house.

Veronique’s questions prick at Alys’s guardedness—she wants to know why Alys is in Korea and pushes about the “Venuses,” famous objects in the shadowy collector world. Alys refuses to explain.

Still, her trained eye catches a fake among Veronique’s treasures, proving her authority and the depth of her family craft.

A lawyer’s message summons her to Gangnam. In a sleek boardroom, Mrs Yoon sits calm but raw with grief, and Ms Han explains the contract: Mrs Yoon will transfer ownership of a notorious item called Elizabeth to Alys, and Alys will destroy it to prevent further harm.

There is a new problem. Mrs Yoon’s adult son, Geon, has secretly visited Elizabeth’s storage chamber and has begun sliding toward the same obsessive pull that ruined his father.

Mrs Yoon now insists Elizabeth must leave Korea immediately and be destroyed within days, not months. Alys resists the pressure, but the sight of Mrs Yoon’s fear changes the tone.

They bargain hard; Alys demands more time and money, landing on two weeks and £250,000. The negotiation is interrupted when Geon storms the hallway, frantic to stop the removal.

Security drags him away while his mother follows trembling after him. In the quiet that returns, Alys understands the deal is sealed.

Alys goes alone to the storage facility. Past coded locks and sterile corridors, she enters Elizabeth’s chamber.

The figure waiting there is uncannily lifelike: a centuries-old clockwork female form on a velvet chaise, breathing as if asleep. Alys feels the aura that has wrecked men’s lives, remembers Mr Yoon once violating her boundaries at a London event, and steels herself.

She addresses Elizabeth with cold familiarity, declares she is taking her home, and carries out the extraction.

The narrative steps back to London, 1769. Eleanor has fled her village with her lover Nicholas, only to be abandoned in Covent Garden when he fails to find work and disappears.

Hungry and desperate, she wanders into Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, where she meets Elizabeth—a glamorous prostitute with sharp eyes and a smooth voice. Elizabeth feeds her, listens, and offers a way forward: come to her King Street house, join a new, high-end brothel she is building, and earn money under her protection.

Eleanor meets Emily, another young woman Elizabeth has “rescued” from a sham marriage trap. Emily privately warns Eleanor she can still walk away, but Eleanor, with no home to return to and no Nicholas to find, accepts.

Elizabeth clothes them in silk and pearls and declares their new life begun.

Back in the present, Alys arrives in London after a long flight. Her flatmate and friend Ro welcomes her with food and teasing, and Alys finally explains the problem: Elizabeth is one of two legendary Venuses, and destroying her will take Ro’s help and the aid of their coven.

Alys is exhausted by the family legacy tied to these objects, but she is fixed on ending it. The next morning they go to Sorrel’s secure art-storage facility.

Two massive crates sit side by side for the first time in over two centuries: Elizabeth’s and Eleanor’s. Alys feels panic rising, expects some supernatural reaction from their reunion, yet senses nothing she can trust.

She refuses to open them. The deadline presses like a hand on her throat.

In 1769, Eleanor learns the rules of her new world. Elizabeth teaches her and Emily how to move through crowds, how to be seen by the right men, and how to mask fear under charm.

Elizabeth’s past leaks through in fragments: a childhood raised as a boy, a violent assault at thirteen, a father hanged for revenge, and years under Mother Wallace, a ruthless madam she later destroyed. Eleanor and Emily grow close, sharing brief warmth inside a cold trade.

But warnings accumulate. A street prostitute tells them Elizabeth once arranged a pox-ridden client to ruin Mother Wallace’s house, killing girls in the process.

The kindness, they realize, can turn.

When illness strikes, the house unravels. Elizabeth collapses with fever, Emily becomes dangerously sick, servants flee, money dries up, and clients retract.

Eleanor discovers letters that show Elizabeth has been auctioning their virginities and taking secret payments. A blackmailed former client, Corbyn, arrives with Dr Chidworth and threatens exposure unless Elizabeth repays a fortune by morning.

The doctor’s crude treatments worsen Emily. In public, a fresh issue of Harris’s List ridicules their “sérail” and claims one girl is infected, one rotting with disease, and one pregnant.

Reading it, Eleanor understands she is carrying a child. Elizabeth explodes with rage and promises revenge, then tells them she has a new plan to save them.

She takes them to an anatomist’s studio in Holborn, a place lined with shrouded bodies, preserved fetuses, and the chill of stored death. The anatomist makes wax models of beautiful women to attract students.

Elizabeth had earlier negotiated a sitting fee; now she returns with a carriage at dusk. She gives Eleanor and Emily sweet wine that is drugged.

As their bodies slacken, Elizabeth reveals her betrayal: she will have them turned into flawless wax Venuses, immortal and profitable, and she frames it as punishment for their disloyalty and a way to outlast ruin. Eleanor collapses into Emily’s arms as darkness takes her.

Eleanor wakes trapped inside a wax form, aware but helpless. The coven arrives through a servant named Lucy, a witch working against Briar—a rival witch aligned with Elizabeth and the anatomist.

Lucy says they can free Eleanor and Emily, but they must burn all the models afterward to end the danger. She cuts a lock of Eleanor’s hair for the spell and warns that when the fire starts, Eleanor must run.

Before the rescue completes, students break in to steal the most valuable model, choosing Elizabeth’s body. Smoke spreads.

Lucy releases Eleanor, who rises back into living flesh and escapes through the alley, surrounded by witches. Later she learns the cost: the fire kills Briar, the anatomist, several witches, and Lucy.

Emily hesitates at the call to rise and stays inside her model; she dies in the flames, but in doing so ensures Briar’s hair necklace—an enchanted tether used to command the Venuses—survives without controlling Eleanor. Eleanor walks away transformed, no longer aging, and vanishes into new names across centuries.

The present-day truth lands: Alys is Eleanor, 273 years old, still living. She gathers with Ro, Sorrel, and Jennet at Rose Cottage to end the cycle by burning Briar’s necklace, the ledger that tracks the Venuses, and Elizabeth’s remains.

But that night, Alys finds Geon in the summerhouse, terrified, and then sees Elizabeth risen in the flesh. Catherine arrives too, boasting of her research and an ancestral knife.

Elizabeth explains how enchanted hair hidden in the knife and ledger let her return. She bends Catherine to her will, orders her to fetch the necklace, and violence follows when Ro tries to intervene and is slashed.

Alys offers herself to spare the others, yet notices Elizabeth’s fear of the necklace’s deeper spell. As the coven chants to open the crystal box, the hair inside begins to sing.

The song triggers Briar’s final trap: instead of empowering Elizabeth, it drags her consciousness back into her wax body, sealing her there. The coven burns the loose hair and the ledger, then incinerates Elizabeth’s wax form at dawn, ending her forever.

With the last bindings gone, only Eleanor’s own model and Briar’s necklace remain. Alys opens the box once more, hears the call to return to the wax, and chooses to accept it so her model can be burned too.

She steps toward an ending she has carried for centuries, ready to close her story beside Emily’s at last.

Characters

Alys (also Eleanor)

Alys is the novel’s emotional and thematic anchor, a woman split across centuries and names. In the present timeline she appears as a highly specialized dealer in mourning jewellery, especially hairwork, with a calm professional surface that masks constant vigilance.

Her expertise is not just technical but inherited, tied to a long family legacy that has taught her to spot authenticity instantly and to treat death as both commerce and ritual. Yet beneath this practiced authority sits exhaustion and fear: she has carried the secret of the Venuses for so long that it has hollowed out normal life, leaving her isolated, suspicious, and always preparing an exit.

The tattoos on her body, especially the phrase declaring ownership of her own fate, are a deliberate assertion of agency in a life where agency was stolen repeatedly. In the historical timeline, as Eleanor, she begins as vulnerable and hopeful, running to London for love and quickly learning how little protection the world offers a poor young woman.

Her transformation into a Venus and subsequent escape, immortality, and reinvention into Alys make her a living contradiction: she survives by refusing attachment, yet her survival is powered by loyalty to the dead—Emily most of all. Her final choice to return to her wax body so it can burn shows that her arc is not about clinging to life at any cost, but about reclaiming control of her ending and setting the moral balance right after centuries of running.

Elizabeth (the historical woman and the Venus)

Elizabeth is the novel’s most magnetic and dangerous presence, a character built from charm, brutality, and an almost mythic appetite for control. In 1769 she enters Eleanor’s life as rescuer and mentor, offering food, shelter, glamour, and survival skills with a confidence that feels like salvation.

She is savvy about the economics of sex work and imagines her érail as a fairer system than the one that broke her, keeping ledgers and presenting herself as a protector rather than a madam. But her kindness is revealed as conditional and transactional; the moment loyalty wavers, her protection becomes predation.

Her past—raised as a boy, raped young, orphaned by violence—explains the hard shell she has forged, yet it does not excuse what she becomes. She weaponizes the same structures that harmed her, turning other women into instruments for her status and revenge.

As the resurrected Venus in the present timeline, Elizabeth embodies the lingering toxicity of beauty fetishized into possession. She is not merely a villain but a personification of coercive desire: seductive, persuasive, and terrified of losing dominance.

Her fear of Briar’s necklace at the climax reveals a core truth about her—power matters to her more than freedom itself, because without power she must face vulnerability again. Her destruction is therefore not only a plot resolution but a thematic severing of the cycle where women are turned into objects for others’ needs.

Emily

Emily is the quiet moral heart of the 1769 storyline, defined by endurance, tenderness, and a fierce instinct to protect others even when she herself is breaking. She arrives already wounded by betrayal through the fake marriage scheme, and that prior trauma makes her perceptive; she reads Elizabeth’s charm more clearly than Eleanor can at first.

Her relationship with Eleanor becomes a refuge in a world that keeps trying to reduce them to commodities. Their shared intimacy in the park—reading, laughing, touching—shows Emily’s capacity to imagine gentleness even when surrounded by threat.

Yet Emily is also practical and sharp; she knows how to invoke Elizabeth’s influence to save them from assault, and she recognizes the danger of staying too long under Elizabeth’s gaze. Her suffering from Chidworth’s corrosive treatment embodies how medicine, like prostitution, can become another arena of male control over female bodies.

The novel’s most devastating ethical pivot belongs to Emily: when Lucy offers the call to rise from wax, Emily refuses at first and chooses to burn, but she does so with purpose, ensuring Briar’s hair necklace survives without controlling Eleanor. That sacrifice turns her into the story’s tragic liberator—someone who cannot be saved but still saves.

Her presence haunts Alys across centuries, not as a ghostly gimmick but as the reason Alys keeps moving toward an ending that honors the bond they once formed.

Nicholas

Nicholas is less complex than the women around him, but his role is crucial as the novel’s first demonstration of how quickly romantic promises collapse under social reality. He begins as Eleanor’s sweetheart and co-conspirator in escape, yet once London’s pressures hit, his inability to secure work exposes both his fragility and entitlement.

He becomes angry, then vanishes, leaving Eleanor stranded. The narrative doesn’t linger on him because it doesn’t need to; his disappearance is the point.

Nicholas represents the risk of staking survival on love in a world structured against women, and his abandonment pushes Eleanor into Elizabeth’s orbit. He is a catalyst for Eleanor’s fall into danger, and also a symbol of the ordinary male irresponsibility that can be as life-altering as deliberate cruelty.

Geon Yoon

Geon is a present-day echo of 1769’s male consumers, but with a more tragic shading. He is the son of Mr and Mrs Yoon, and the one person whose fate scares his mother enough to hire Alys to destroy Elizabeth.

Geon’s frantic arrival at the boardroom, his terror at the storage facility, and his later appearance pale and shaking in the summerhouse suggest someone caught between fascination and fear, leaning toward obsession because it has been modeled for him as inheritance. He isn’t framed as evil; rather, he is framed as vulnerable to the Venus’s lure and to the seductive mythology built around her.

His intrusion into Alys’s life is the living proof that the Venuses don’t just sit in crates—they pull at people’s minds, especially those already reshaped by grief, family power, or curiosity. Geon’s presence intensifies the moral urgency of Alys’s task, because saving him from obsession becomes part of saving the world from Elizabeth’s continued influence.

Mrs Yoon

Mrs Yoon is composed, grieving, and remarkably strategic, a woman who has learned to survive inside wealth and patriarchal power without being swallowed by it. Her private contract with Alys shows long-term planning and a willingness to do morally murky things to protect her son.

She seems to genuinely believe Elizabeth is a corrupting force that destroyed her husband and will destroy Geon next, and that conviction makes her both sympathetic and chillingly pragmatic. Her negotiation style reveals steel beneath sorrow: she tries to compress Alys’s timeline not out of greed but panic, and she accepts being seen as desperate if it means Geon might be spared.

The moment she calls Alys a monster isn’t petty insult; it is grief speaking through terror, because she needs to believe only a monster could handle something so dangerous. She is a portrait of maternal love shaped into ruthlessness by the scale of what she is fighting.

Mr Yoon

Though already dead when the modern plot begins, Mr Yoon’s shadow dominates the stakes. His obsession with Elizabeth, his violation of Alys at the London event, and his role in exposing Geon to the Venus define him as someone who treats beauty and women’s bodies as collectibles rather than lives.

He is a modern parallel to the aristocrats and anatomists of 1769: a man of money and taste who believes he is entitled to possession. His death functions like a trigger for the story’s final movement, but more importantly it shows that the Venuses’ danger is not only supernatural—it is social.

They thrive in the fantasies of powerful men like him.

Ms Han

Ms Han is the modern plot’s embodiment of institutional precision. As Mrs Yoon’s lawyer she manages logistics, contracts, and risk with cool professionalism.

She doesn’t moralize; she facilitates, negotiates, and shields her client. Her role is significant because it shows how the Venuses are not just occult secrets but assets moving through legal and financial systems.

By warning Alys that Mrs Yoon called her a monster, Ms Han also acts as a mirror—she acknowledges the human cost of Alys’s work without trying to stop it. She represents the world that makes room for horrors as long as paperwork is correct.

Veronique

Veronique is an important lens on obsession from a different angle than the Yoons. She is wealthy, aesthetic-obsessed, and genuinely thrilled by the artistry of mourning objects, living inside a home that mirrors her stark, controlled sensibility.

Her collection of eye miniatures and hair jewellery shows devotion to beauty born from death, and her probing questions about the Venuses reveal curiosity that borders on predatory fascination. Yet she is not a villain; she is a refined collector who sees herself as a guardian of rare things.

Her function in the narrative is to underline Alys’s uneasy position—selling grief as art while hiding the line where collecting becomes corruption.

Ro

Ro is Alys’s anchor in the present, providing warmth, humor, and pragmatic loyalty without demanding complete disclosure. Their domestic scenes—shared cooking, ginger candies, jokes about odd specimens—are not filler; they show what Alys could have if she were free of the Venuses’ burden.

Ro’s expertise is also vital: she understands that Elizabeth is not a normal wax figure and is willing to help destroy her despite the danger. Her connection to the coven places her in a lineage of women resisting the Venuses across time, but her personality keeps that lineage grounded in lived friendship rather than mystique.

When she is slashed protecting others, it confirms her courage and deepens the sense that resistance is costly. She stands for chosen family and for the possibility of trust in a life built on secrecy.

Sorrel

Sorrel operates at the intersection of commerce and witchcraft, an antiques dealer allied with the coven who helps with storage, transport, and practical arrangements. Her banter with Ro and her warm greeting to Alys show someone who can hold darkness lightly without trivializing it.

Sorrel’s role emphasizes that the coven is not made of ethereal sages but real people with jobs, jokes, and logistics to handle. She is a steady presence, the type of person who makes survival possible through competence.

Jennet

Jennet is a senior member of the coven and a figure of calm authority in the final act. She is less individually spotlighted than Ro or Alys, but her importance lies in steadiness and collective memory.

The coven’s chanting, protection spells, and coordinated burning depend on knowledge passed down and guarded over centuries, and Jennet seems to embody that continuity. She represents communal responsibility: where Alys carries guilt alone, Jennet carries it with others, showing that the only way to end something like Elizabeth is together.

Catherine

Catherine is the modern seeker whose curiosity becomes a threat, not because curiosity is evil, but because she wants knowledge without understanding the cost. She suspects Alys is hiding more than her mother’s whereabouts and pushes close enough to send Alys spiraling into flight.

Her later arrival at the summerhouse with an ancestral knife and research shows ambition to be part of the story’s hidden truth. Catherine’s flaw is not cruelty but overconfidence; she believes lineage and study will protect her from forces that don’t care about her intentions.

Elizabeth’s easy hypnosis of her exposes how quickly righteous certainty can be turned into a weapon. Catherine functions as a warning about obsession in its early, human stage—before it hardens into someone like Mr Yoon.

Briar

Briar is a historical force of manipulation whose magic bridges timelines through the enchanted hair necklace and the hair-stuffed knife handles and ledger spine. She is aligned with the anatomist and Elizabeth in 1769, using hair as a medium for control, turning women into living wax vessels.

Her spells don’t just restrain bodies; they warp identity, leaving Eleanor traumatized and altered long after escape. Briar’s death in the original fire might seem like an end, but her “final alteration” embedded in the necklace proves she thought beyond her lifetime, designing a trap that ultimately undoes Elizabeth centuries later.

She is a portrait of power that outlives the wielder—cold, meticulous, and devastatingly intimate, because it works through stolen pieces of the body.

Lucy

Lucy is one of the novel’s most luminous figures, a good witch who risks everything to free Eleanor and Emily. Her intervention arrives at the bleakest moment, offering not comfort but a concrete path out, complete with a clear moral cost: the Venuses must be burned afterward.

Lucy’s taking of Eleanor’s hair is not violation but rescue, turning hair into a tool of liberation rather than captivity. Her death in the coven’s fire casts her as martyr, and her legacy persists in the coven’s vigilance up to the present day.

She represents ethical magic—power used with consent and sacrifice.

Dr Chidworth

Dr Chidworth is a historical embodiment of medical harm intertwined with exploitation. He is Elizabeth’s doctor, but instead of healing, his treatment of Emily becomes another form of violence, leaving her infected and in agony.

His presence shows how institutions that claim authority over bodies can collude with those who profit from bodies. He also becomes a tool of blackmail and intimidation through Mr Corbyn, revealing medicine as part of the same ecosystem of male control that the women are trying to survive.

Sir William Kettering

Sir William is a complex male figure who illustrates patronage as both survival and humiliation. As Elizabeth’s former keeper he represents a kind of sanctioned dependence: he funds her, enjoys her, then publicly replaces her with a fiancée who must glare at the reminder of his past.

Yet he is not uniformly cruel; when Eleanor appeals to him for medical help, he responds, sending a superior physician and unintentionally exposing Chidworth’s harm. His role highlights the unstable power women hold through men’s desire—useful, temporary, and always at risk of turning into disgrace.

Mother Wallace

Mother Wallace is a spectral presence of the older brothel system Elizabeth escaped and reshaped. She embodies the brutal lineage of exploitation in which women train and profit from other women because society offers no other structure.

Her humiliation and destruction by Elizabeth underline how vengeance circulates within oppressed communities, turning victims into enforcers and rivals. She is a reminder that Elizabeth didn’t invent cruelty; she inherited it and amplified it.

The anatomist

The anatomist is a historical villain whose studio fuses science with fetish. He creates wax models for education, but his interest in “beautiful figures” and his collaboration with Briar and Elizabeth reveal how easily knowledge can be corrupted into possession.

He treats female bodies as raw material for display and profit, and his studio becomes the literal site of transformation from human to object. His confident defense to the Bow Street Runners, and the student theft that follows, illustrate a broader culture that normalizes this objectification.

He is less an individual psychology than a system made flesh.

Lord Levehurst

Levehurst and his friends represent aristocratic entitlement at its ugliest. He is targeted by Elizabeth as a client for Eleanor’s virginity, and his friends’ assault on Eleanor and Emily shows that for men like them, “sport” is violence without consequence.

They function as a social weapon Elizabeth tries to manipulate, but they also reveal the limits of her control. Their presence makes clear that the Venuses are born from a world where male desire is law and female safety is illusion.

Themes

Agency, autonomy, and the cost of choosing for oneself

Alys moves through the present timeline with a sharp sense that her life has been shaped by other people’s hungers and by inherited obligations. Her repeated mantra, “I am the mistress of my own fate,” is not a decorative affirmation; it is a practiced defense against a world that has tried to claim her body, her labor, and even her time.

Her profession in mourning jewellery already sits at the border between intimacy and commerce: she handles hair, grief, and memory for clients who want to possess the past in wearable form. That work mirrors her larger battle with the Venuses.

The secret contract with Mrs Yoon and the urgency around Elizabeth force Alys to confront what autonomy means when your skills and history make you valuable to others. She negotiates hard, not just for money but for control over the timeline and method, and that negotiation becomes a statement that her boundaries matter even in the face of wealth and panic.

Yet autonomy here is never simple. Alys’s choice to destroy Elizabeth is also a choice to carry risk, trauma, and moral burden.

The story shows how power can demand sacrifice: acting freely often means accepting loneliness, danger, and the possibility of being judged monstrous by people who benefit from your actions.

In the historical timeline, Eleanor’s search for freedom is more desperate and more precarious. When Nicholas vanishes, her “choice” is narrowed to starvation, exposure, or entering Elizabeth’s protection.

The offer is framed as rescue, but it is also recruitment into a system that monetizes her body and inexperience. Eleanor’s later decisions—staying, trusting, planning escape, and finally accepting Lucy’s call to rise—show autonomy as something that is repeatedly threatened, then rebuilt in small acts of will.

Even immortality for her is not a gift she selects; it is an outcome of surviving someone else’s plan. By placing Alys and Eleanor as the same person across centuries, Slashed Beauties turns autonomy into a long struggle rather than a single triumph.

The ending, where Alys chooses to return to her wax form so it can be burned, is the purest crystallization of this theme: the last meaningful act of control she can claim is over her own ending. The narrative argues that agency is not proven by living forever or winning every fight, but by insisting on the right to decide what your life and death will mean, even when the world offers only brutal options.

Objectification, the commodification of bodies, and resisting being turned into an artifact

The Venuses are literal embodiments of objectification: women transformed into teaching tools and luxury curiosities, admired for their beauty while stripped of voice and personhood. Elizabeth’s wax body was originally a medical model designed to entice male students, an origin that makes clear how educational and erotic uses of women’s bodies can merge under patriarchal control.

Present-day collectors such as Mr Yoon and Veronique extend that tradition. Their fascination with hair jewellery, eye miniatures, and the Venuses shows a desire to own fragments of human intimacy without reciprocity.

Alys’s expertise lets her move among these collectors, but she is never fully safe from their gaze. The London memory of Mr Yoon grabbing her hair is a small but searing instance of the same impulse: the collector who believes he is entitled to touch, take, and claim.

That violation is what propels Alys to cut her hair short and vow to remove Elizabeth, signaling her refusal to be treated as a collectible extension of her craft.

In Eleanor’s era, objectification happens through prostitution, but not in a simplistic way. Elizabeth’s “sérail” is marketed as protection and elegance, yet it is also a structure for auctioning virginity, tracking gowns and jewels as if the women wearing them are inventory.

Men in St James’s Park and at the theatre view Eleanor and Emily as entertainment, prey, or trophies. Even the Harris’s List satire that mocks them shows how quickly female bodies can be publicly reduced to rumor and commodity.

Elizabeth herself sits in a complicated position: she is both victim of earlier violence and an active agent in reproducing objectifying systems for profit and revenge. Her final betrayal—drugging Eleanor and Emily and selling them into wax eternity—reveals the terminal logic of commodification.

To preserve beauty, she has to erase life. She doesn’t just treat them as assets; she makes them into permanent objects for male consumption and historical curiosity.

Alys’s present-day mission to destroy Elizabeth is, therefore, not merely about stopping a supernatural threat. It is a radical refusal of object status.

She takes the object back from the collector and the museum logic of preservation. The coven’s fire and the later burning of Elizabeth’s body and ledger are acts of cleansing that reject the idea that women should exist to be displayed, studied, or owned.

Even Alys’s ultimate choice to return to her own model so it can be burned rejects the seductive trap of being “perfect forever. ” Slashed Beauties uses horror to expose a cultural habit: admiration can be another mode of violence when it seeks to freeze living people into artifacts.

Resistance here means asserting that beauty without consent is just another kind of possession.

Grief, memory, and the ethics of holding on

The book’s obsession with hairwork, wax bodies, and ledgers runs on the same fuel: the desire to keep what is gone. Alys’s trade in mourning jewellery shows grief as something that people try to domesticate through objects.

Hair is intimate yet durable; it promises a physical trace of a life that can be carried forward. Clients like Veronique build collections that function like private mausoleums, carefully arranged to turn loss into aesthetic experience.

These items can be tender, but they also flirt with fetish. Alys stands at the ethical edge of that practice.

She is skilled at authenticating the past and is proud of a family lineage that honors the craft, yet she also recognizes how grief can be exploited or distorted when it becomes a marketplace. Her clients’ hunger for rare pieces mirrors Mr Yoon’s dangerous fixation on Elizabeth, implying that some forms of memorializing become destructive when they refuse to accept an ending.

Mrs Yoon’s bargain with Alys is a different kind of grief story. She is mourning her husband, but more urgently she is mourning what obsession did to him and fearing what it will do to Geon.

Her demand that Elizabeth be removed and destroyed is a grief-driven attempt to break a cycle. She is willing to sacrifice continuity, heritage, and an expensive possession to protect her child from an inherited madness.

This suggests grief can be protective rather than merely nostalgic: sometimes the ethical act is not to preserve but to let go. Alys becomes the executor of that ethic, though it costs her peace, safety, and the chance to live unburdened by her legacy.

The historical timeline builds a darker version of memory. Elizabeth’s ledger and the enchanted hair necklace are tools for preserving control through traces of the body.

Hair becomes a conduit not for comfort but for binding. The necklace survives fire, time, and death because it is made from stolen pieces of women’s bodies, turning memory into captivity.

Eleanor’s immortality similarly becomes a living memory she cannot escape. She carries Emily’s death, Lucy’s sacrifice, and the coven’s failed rescue for centuries.

That weight shapes her secrecy and exhaustion in the present. She doesn’t just remember trauma; she is forced to be its ongoing witness.

When the coven finally burns the necklace, the ledger, and Elizabeth’s body, the story frames destruction as a moral response to toxic remembrance. Not all preservation is respectful.

Some keepsakes are traps. The closing act—Alys writing “Debt settled in full” and then choosing her own incineration—recasts letting go as love and justice rather than loss.

Slashed Beauties insists that memory should serve the living, not imprison them. Grief is natural, but clinging to the wrong relics can extend harm across generations, and the bravest form of mourning may be to end what should not survive.

Power, manipulation, and the seduction of control

Elizabeth’s presence dominates both timelines as a study in charisma turned coercive. In 1769 she enters Eleanor’s life as rescue, glamour, and certainty.

She offers food, shelter, clothes, and a narrative of sisterhood, and those gifts create real relief for a girl who has been abandoned. Yet Elizabeth’s kindness is never separate from her appetite for dominance.

She trains Eleanor and Emily like investments, parades them through crowded spaces so rich men will notice them, and scripts their expressions to draw desire. Her ledger, presented as fairness, is also surveillance.

She creates dependence by paying their costs and then claiming half their earnings, narrowing their exits even as she claims to protect them. The story makes clear that manipulation is often most effective when it is packaged as care.

Elizabeth’s past trauma explains but does not excuse her methods. She learned early that men and madams could take everything, so she builds a world where she cannot be the one taken from.

Her revenge against Mother Wallace by spreading pox-ridden infection shows how control, once fetishized, escalates into cruelty. The drugging of Eleanor and Emily is the final proof that Elizabeth values command more than companionship.

Even their beauty is not for their sake; it is for her triumph over vulnerability. The fact that she turns them into Venuses “forever” is a perverse form of love that erases the beloved to guarantee possession.

In the present, Elizabeth’s power has mutated into supernatural influence. Mr Yoon’s obsession and Geon’s frantic terror show how the Venus operates like an addictive object, drawing desire while stripping autonomy.

Mrs Yoon’s fear that Elizabeth will “destroy” her son as she did her husband indicates a long pattern of psychological corrosion. Even absent, Elizabeth exerts pressure.

Alys herself feels nausea and dread in the storage facility, and her expectation of some sensation when the crates reunite suggests she knows the Venuses can act on the mind. That expectation, and her disappointment when nothing obvious happens, also reveals how manipulation can be subtle—working through anticipation, myth, and fear.

The coven represents another angle on power: collective protection, ritual, and secrecy. Their spells and charms are meant to counter control with care, but their history with Eleanor shows that even protective power can fail, cost lives, and create long obligations.

Alys’s distrust of being “watched over from afar” hints at the tension between guardianship and intrusion.

The climax in Rose Cottage reframes control as something that can be reversed. Elizabeth tries to use Catherine as a pawn and demands the necklace, but the necklace’s song is the hidden counterspell that drags her back into wax.

The story suggests that domination often carries its own vulnerability: the very tool that grants power can become a cage when its deeper logic is turned against the wielder. Slashed Beauties portrays control as seductive because it promises safety, status, and revenge, but it also shows how that seduction hollows out empathy and eventually selfhood.

Power without consent is not strength; it is a kind of starvation that consumes both victim and aggressor.

Female solidarity, fractured sisterhood, and survival through community

Relationships between women are the emotional engine of the novel, and they are drawn with both warmth and betrayal. Eleanor’s early bond with Emily is one of the few spaces in 1769 London that feels safe.

Their day in St James’s Park reading together, their shared awe and fear, and Emily’s quick thinking when men assault them show a kind of solidarity that is practical, tender, and life-preserving. This sisterhood is not sentimental; it is forged under threat, and that makes it more urgent.

When Emily warns Eleanor about Elizabeth’s danger, she is trying to keep another woman alive in a world that profits from their harm.

Elizabeth complicates the idea of sisterhood by performing it while undermining it. She frames her household as a refuge from cruel brothel practices, speaks of fairness, and positions herself as protector.

At times she is sincere in wanting to create a better arrangement. But her leadership is also hierarchical and possessive, demanding loyalty while withholding truth.

Her manipulation fractures trust between the girls, and her final act of betrayal turns a supposed community into a trap. The result is that solidarity in this timeline is constantly tested: survival sometimes requires closeness, and sometimes requires seeing through the false sisterhood of someone who wants devotion without mutuality.

Emily’s last choices capture this tension. She first wishes for Elizabeth’s death out of desperation for freedom, then later refuses the call to rise, choosing to burn.

Her refusal is not weakness; it is a final act of meaning-making that keeps her bond with Eleanor intact in the way she can manage. She ensures the controlling hair necklace survives but no longer binds Eleanor, giving Eleanor a chance to live free.

Even in dying, she chooses her friend’s survival over her own rescue.

In the present, Alys’s bond with Ro reflects a healthier version of community. Their kitchen scene is playful and ordinary, full of food, care for nausea, and shared oddities of work.

This normalcy matters because it shows Alys is not only a haunted immortal; she is someone who can still belong. Ro’s immediate agreement to help destroy Elizabeth, and her willingness to alert the coven, show trust built on shared values rather than coercion.

The coven itself is a multigenerational structure of female protection. Unlike Elizabeth’s sérail, their rituals are aimed at release, not captivity.

Yet the story doesn’t idealize them as perfect. Their earlier fire cost lives, and their watch over Eleanor for centuries suggests a complicated mixture of care and surveillance.

Alys’s exhaustion with the legacy indicates that solidarity can become another kind of burden if it removes choice.

The final collaboration at Rose Cottage—Ro returning with the crystal box, Jennet and Sorrel joining, the coven chanting, and Alys making the last decision—shows survival as collective labor. No one woman can end Elizabeth alone, but no one is erased in the process.

Slashed Beauties argues that sisterhood is powerful not because women are naturally virtuous, but because community allows resistance to systems that isolate and commodify them. At the same time, it warns that solidarity must be rooted in consent and truth, or it becomes another tool of domination.

The novel’s hardest-earned hope is that broken sisterhood can be rebuilt into something that frees rather than owns.